How do patients come to the decision regarding whether or not to initiate dialysis? Well, that is the question that we talk about with Keren Ladin on this week’s podcast. Keren is a social science researcher, bioethicist, and assistant professor in the department of Occupational Therapy at Tufts.

What becomes clear when you look at Keren’s research is the for many patients, there isn’t a decision that is made. As Keren said in our podcast:

We had asked people all these what we thought were thoughtful questions about, “Can you tell us more about what were the factors that were involved and how did you come to this decision”… and eventually we just got back two different options. One was that it wasn’t really a decision at all, that they had felt that they needed to start it or that they would kind of die immediately, or that it wasn’t their choice, it was more of their physician’s choice, which we thought was also really interesting.

To read more about the articles we discuss, click on the following links:

- Discussing Conservative Management With Older Patients With CKD: An Interview Study of Nephrologists. Am J Kidney Dis. 2018 May;71(5):627-635.

- “End-of-Life Care? I’m not Going to Worry About That Yet.” Health Literacy Gaps and End-of-Life Planning Among Elderly Dialysis Patients. Gerontologist. 2018 Mar 19;58(2):290-299.

- Engagement in decision-making and patient satisfaction: a qualitative study of older patients’ perceptions of dialysis initiation and modality decisions. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2017 Aug 1;32(8):1394-1401.

- John Oliver clip on dialysis

Eric: Welcome to the GeriPal podcast. This is Eric Widera.

Alex: This is Alex Smith.

Eric: Alex, who is our guest today?

Alex: Today we have a guest from Boston on the other side of the country. We have Keren Ladin who is an Assistant Professor. She’s in the department of Occupational Therapy at Tufts. She is a social science researcher. She is a Bioethicist. Welcome to the GeriPal podcast, Keren.

Keren: Thanks. Happy to be here.

Eric: So we always start off this podcast with a song request. Have you got a song for Alex?

Keren: Sure. Can you play Weezer’s “The Sweater Song”?

Alex: [Singing].

Eric: That’s about as much singing as you’re ever going to get out of me.

Alex: That’s pretty good. We got Eric to sing! That’s unusual. He likes the Weezer.

Eric: Again, thanks for joining us, Keren. Before we start talking about some of the work that you’ve done around dialysis, how did you get interested in this subject?

Keren: That is a good question. I think I got initially interested in dialysis through some of the research that we had done with kidney transplant patients. We had a pretty large study going on with patients who were thinking about transplant and looking at their decision making processes. We spent a lot of time in dialysis centers and just, you know, talked to a bunch of patients, some older patients especially, and learned a little bit about kind of what their process was like. I think really just through spending those hours in the centers and with nephrologists and surgeons, I became really interested in what goes into a decision to initiate dialysis, which is kind of such a life changing therapy.

Alex: Yeah so tell us about these studies that you did. I don’t know if it’s easier to start with the patient side or with the physician side about this issue of initiating dialysis.

Keren: Yeah. For me it really started with the patient side. I think going into thinking about kind of for people trained in health policy, I think oftentimes what’s interesting to us is when there’s kind of a very big difference between treatments either between countries or things like that, so there had been a series of papers that had come out looking at treatment of older adults with and without dialysis in the U.K. What was really interesting is that they had kind of a very different kind of baseline for what would qualify for dialysis treatment. Not everybody was referred. It’s wasn’t kind of inherent that people would just start dialysis. Instead it was this more deliberative decision making process.

So I was interested to see how that would work in the U.S. When we started talking to patients about eight years ago now, what became really clear is that most patients did not experience a decision at all. It really changed the way we decided to study this. We had asked people all these what we thought were thoughtful questions about, “Can you tell us more about what were the factors that were involved and how did you come to this decision,” and all of this, and eventually we just got back two different options. One was that it wasn’t really a decision at all, that they had felt that they needed to start it or that they would kind of die immediately, or that it wasn’t their choice, it was more of their physician’s choice, which we thought was also really interesting.

Alex: You have some great, I mean disturbing, quotes here about the patients’ perspectives on starting dialysis, and I’ve kind of underlined a few here. How much autonomy, for example, do the patients feel that they have in making these decisions? “The kidney doctor is the one that said that I should have dialysis.” “Lying on the bed three hours a day is not my way of living.” “They had a hard time convincing me. I finally did agree.” “Sometimes you feel like you don’t have a choice.” Then, “They said if I didn’t do dialysis, I might as well plan my funeral.” This is really stark, right? As you were saying earlier, in Europe it does sound like there are choices here, patients may feel more engaged in the process of decision making. They may feel like they have a choice, and there may actually be a choice because there’s another option, conservative management. It doesn’t sound like these patients feel like they have much of a choice here in the U.S.

Keren: Yeah. I mean I think that it was really striking to us as well, and hearing these patients and hearing them kind of recount their narratives that they really felt very strongly that they didn’t have a hand and that they really didn’t have a decision point, kind of to the extent that they were surprised or confused about even the question, about, “What else would I have done?” To us, I think from a policy perspective, especially it’s really important because for many of the patients, especially that we were interviewing, they’re older patients. They have many comorbidities. It really seemed to be more of a question of dialysis initiation as a quality of life choice as opposed to necessarily increasing longevity, and yet for most patients, they really didn’t have any sense that this was an option that would affect their quality of life and that there were others that they could choose from as well.

Alex: Let me just reiterate what you said there. Make sure I understand it. For the patients, it seemed like they were more interested in quality of life concerns, but the physicians were presenting this as an issue of survival and length of life. Does that summarize some of …

Keren: Yeah.

Alex: Yeah.

Keren: Yeah. That’s right. That’s right. It wasn’t clear to us kind of why that was, why were nephrologists really focused on this, on survival as opposed to quality of life. Is it that they really thought that dialysis was going to prolong the life of these patients in particular, or did they know or were aware of the literature about conservative management? Why did they not engage in these kinds of conversations and why didn’t they tell patients more about their prognoses? What was interesting was actually the National Kidney Foundation president, Jeff Barnes said in one of his speeches at the kidney conference a few years ago, he said that patients care about quality of life above all else, but too often health care providers and family members are only focused on mortality. That’s really what we found. That really resonated with our patients’ experiences.

Alex: And that’s a nice bridge to talking about the other paper. Eric, did you have a question?

Eric: Yeah. This other paper that you just got published in American Journal of … is it Kidney Diseases? AJKD?

Keren: Yeah.

Eric: Discussing conservative management with older patients with CKD, an interview study of nephrologists. What did you learn about the kidney doctors and how they’re thinking about this?

Keren: Yeah. It was really interesting. After kind of having these conversations with patients, we came away with the thought that they really were under-informed about their options. Sometimes there’s a discrepancy between what patients report and remember and what they were actually told, or what the doctors perceive that they told them. We thought it would be a good idea to interview nephrologists and ask kind of what they were telling patients, older patients who are facing dialysis decisions, as kind of a matter their standard practice.

We interviewed 35 nephrologists from 18 practices across the country. About a third described routinely discussing conservative management with their patients. That’s to say two thirds did not do that. We found that there were a lot of barriers in how nephrologists perceive their own role and the potential consequences of describing conservative management to older patients. There was a sense that they were kind of ill-equipped to have these conversations or there was a sense that they didn’t want to deprive patients of hope. A strong preference, as we see, kind of in the applied ethics and economic literature towards kind of active treatment options. They were viewing conservative management as no care. Confronting a lot of institutional barriers to offering conservative management.

Eric: Can you describe what those institutional barriers were?

Keren: Yeah. This was true for both academic and community-based practices. There was a lot of concern over time constraints. There was a perception that kind of a discussion of conservative management required more time. You know, you might encounter a lot of pushback or patients shutting down, and providers were not sure how to handle that kind of within the context of their regular visit. There was difficulty with care coordination, especially with social workers or with palliative care or with primary care, and the thought was that if a nephrologist is going to offer conservative management, they really need all these other providers to be on board so that the patient doesn’t get mixed signals or isn’t kind of started on dialysis emergently. I know that that’s a challenge that nephrologists feel. Finally there’s a lot of financial incentives for offering dialysis. A number of nephrologists voiced their concerns about not fully understanding the financial model around conservative management and what that looks like and whether it would be supported by their institution.

Alex: That is a key driver right there.

Keren: Yeah.

Alex: You actually sent me a link to this fantastic John Oliver segment. We were just watching a little bit of it again, here.

Eric: We’ll have it on our GeriPal post attached to this blog.

Alex: We’ll have that link. He goes into the sort of economics that’s sort of a major driving force, in particular calling out DaVita, one of the major dialysis companies, about the ways in which they have really designed their business model around maximizing profit for shareholders rather than providing the best care for patients with chronic kidney disease. It’s both hilarious and, of course, disturbing as many of John Oliver’s segments are. I don’t know if you wanted to say anything about that John Oliver sketch.

Keren: Yeah. I mean I think that in the past year or year and a half there’s been a lot more attention to this, with John Oliver, who really does, I think, the best job of integrating the funny and kind of dramatic and desperate aspects of this, but also the Boston Globe and many other papers have written about this. I think it is unique in American health care compared to other countries, that a large part, or the vast majority of dialysis care is provided by private companies. There are these kind of competing incentives in terms of providing dialysis and even referral to transplant. I think overall people are optimistic that things are moving in the right direction, it’s just that they’re moving very slowly. We’re hopeful that some of this research can kind of help at least identify some of the levers and mechanisms for change.

Eric: You also discussed in your AJKD article that providers feel some moral distress over this too. Is that right?

Keren: Yeah. What was really interesting to us was, I think in speaking with the patients and hearing about their stories and the really moving narrative that they shared with us, it was hard to see how and why nephrologists would withhold this information. I think in speaking with nephrologists we really understood kind of how deeply divided they are over their role and how difficult it can be for them, both in cases where conservative management should have been offered and followed and a patient gets kind of emergently dialyzed, to pretty devastating consequences, as well as the reverse where they have these longstanding relationships with patients and they offer them conservative management and the patient may feel abandoned or they may feel like the nephrologist is withholding care.

With respect to kind of the moral distress aspect, we did see that many nephrologists who changed their practice, who started offering conservative management more routinely, did it as a result of kind of these very salient encounters or experiences with patients where they remembered that there was this horrible outcome, this patient who was, to quote them, “tortured at the end of life” and that they felt that there had been a better option and that they had wished that they were more vocal at the time. Actually those nephrologists who now routinely offer it and kind of described to us the evolution of their approach, tend to feel better about whether or not their patient chooses conservative management. They feel like they’re offering the best standard of care.

Alex: That’s terrific. I just want to read a few more of these quotes because they’re just so striking and sort of bring home, crystallize these perspectives. Here’s one nephrologist who’s saying, “I view myself as someone who tries to provide a ray of hope for people who are sick. I’ve seen enough people who feel so much better after dialysis.” They feel like they have to offer it because they have to offer some hope and they don’t see conservative management as hope. Here’s another quote, “I let her go six months because she didn’t really exhibit symptoms. She’s like, ‘I feel fine.’ Then one day she walked in and I said, ‘That’s enough. I’ve given you your time and now I think we have to get you into dialysis.” Really sort of turning the screws on people who are choosing conservative management. Then finally about prognosis, discussing the tremendous uncertainty in prognosis for patients with chronic kidney disease, “I don’t know the answer to prognosis questions. I actually don’t address prognosis.”

Eric: Is that the same thing you heard from the patient side, is physician unwillingness to discuss prognosis?

Keren: Yeah. For the most part, our work and many others have found that even, as you guys know this really well, even when the prognosis is really dire, patients want to know. Most patients want to know. We certainly heard that from patients that we spoke with. I think part of the difficulty with nephrologists especially here is that they have these really longstanding relationships with the patients and they don’t want to injure those relationships in any way. I think, to some degree, they may be optimistic anyway, so we did hear from a lot of nephrologists as kind of like Wobegon effect, “I know that conservative management on average may offer the same survival as dialysis for older patients with comorbidities, but my patients do better than average.” We heard that, that was a refrain among many.

Yeah, from patients we did hear that they wanted to know their prognosis, and some of them, to the degree that this wasn’t brought up, felt like it wasn’t brought up because it wasn’t relevant to them. When we asked them, “Did your doctor ever tell you … Did you talk about advanced care planning? Did you talk about end of life? Did they ever use the word prognosis or talk about how much time you might have left?” They said, “No, that doesn’t apply to us. We’re obviously not in that stage or our doctor would tell us.” That was really difficult to hear.

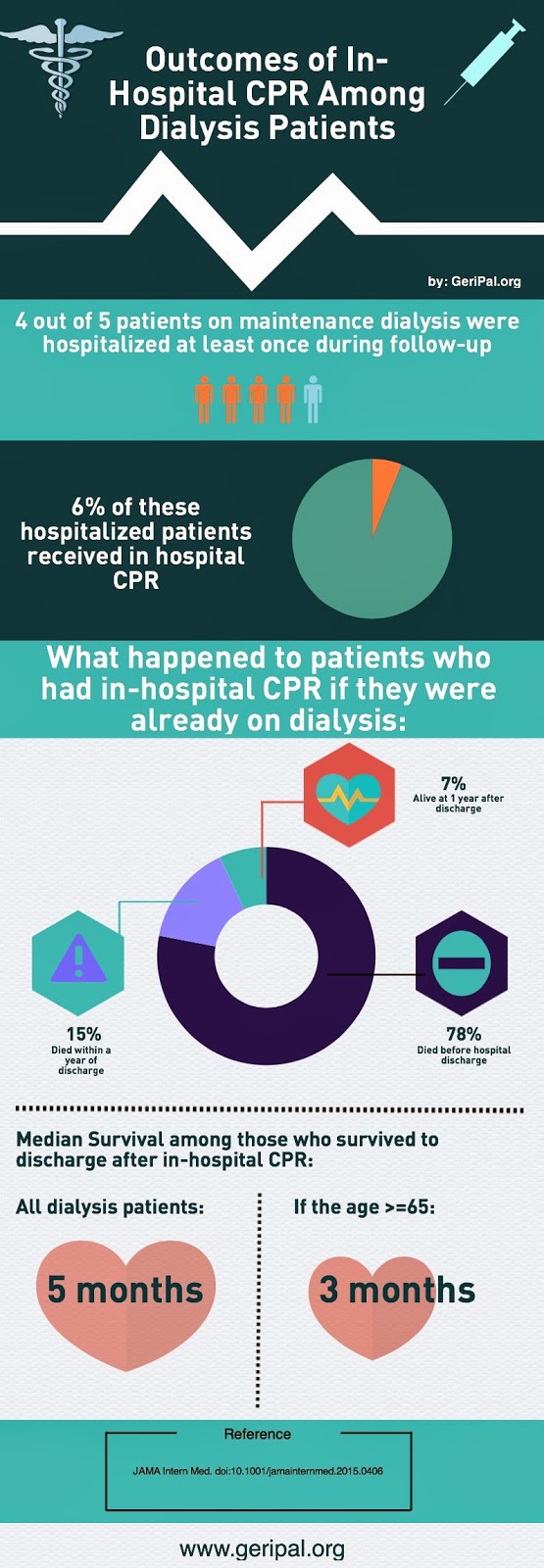

Alex: You also have this other paper in the Gerontologist titled, “End of Life Care? I’m Not Going to Worry About That Yet.”, that’s a quote, “Health Literacy Gaps and End of Life Planning Among Elderly Dialysis Patients.” In this study you found that, you know, as we know, very high risk for mortality with dialysis. With chronic kidney disease, as John Oliver noted, is the ninth leading cause of death, and I’m sure it’s a comorbid illness for many other causes of death. Yet despite that, only 13% of patients that you studied here in these 31 elderly dialysis patients had discussed end of life preferences with physicians. You found some serious concerns about health literacy and misunderstandings. Do you want to say a little bit more about what you found there?

Keren: Sure. Yeah. Like I said, very few patients have had any kind of conversation about advanced care planning or about the severity of their illness. What we learned was that there were a lot of misunderstandings even in commonly used terminology that we took from the literature, kind of patient handouts, that the nephrologist offered patients. What was striking to me was actually the word intervention. Oftentimes what we found was that patients didn’t realize … They understood the degree to which they would have to come to the clinic for dialysis, that dialysis might involve needles, but they didn’t understand that they might need a surgical procedure to create a fistula and fistula maintenance and all of that.

The nephrologists, when there were describing it, were often using the word intervention. Patients, many of them were actually put off by this word. I think it kind of coincides with reality TV shows about interventions with families. And so many people kind of understood word to be like an intervention. One said to us, “I don’t need an intervention. I don’t have any problems of that nature.” That kind of thing.

Eric: I love the words that we use and recognizing like, “Oh, that’s not how most people perceive that.”

Alex: Reality check. Right.

Eric: The test was negative.

Alex: Right.

Eric: Oh my God, it’s negative. I’m going to die.

Keren: Yeah. That was really an eye opener for us, and we had to think kind of long and hard even about the questions that we were asking. Yeah. I think there needs to be a lot more attention to kind of health literacy around end of life conversations and what are patients walking away with? Are they understanding it?

Eric: It also sounds like from your papers that the patient also feels like they have a role to play and their role is to be the patient, and potentially that is not challenging physicians with some of these things, including discussing prognosis. One of your lines said patients frequently felt shut down by physicians when asking about implications of dialysis for quality of life and prognosis and they didn’t feel comfortable initiating these discussions.

Keren: Yeah. That came through. I think what’s really interesting is both nephrologists and patients feel really uncomfortable having these conversations and don’t feel like it’s their role. The patients really did … I think especially given that it’s end of life or last stage of life kind of conversations, it was really troubling and distressing to hear them kind of not feel like they could get an answer or that they could really push on their nephrologist to address their concerns. Yeah. It’s troubling.

I think even worse though, one of the things that came out of the patient interviews is that for many patients who chose dialysis, dialysis became their job. They described kind of this new stage of life where they are now trying to be a “good patient”. They would talk about kind of what that involved, and that involves coming to all of their dialysis sessions and their follow up visits and their diet and all of these things. When we asked them about their preferences and goals overall, what was important to them in life, there were very limited overlaps in terms of kind of what the patients thought that they wanted to do in their last stage of life and what they actually were doing, in terms of limited social participation and kind of even the symptoms of fatigue and appetite were not really resolved by the dialysis for many of them. Many of them kind of vocalized their desires, especially as they’re aging, to travel, which is possible on dialysis, but it’s difficult. They kind of wish they would have known that.

Alex: This is terrific. Your work is really sort of granular, grounded in the experience of patients and doctors who are grappling with this in the U.S. Can we take a step back now and look sort of more bigger picture? What do you see as the major things that need to be done in order to change the system, the culture, our approach to these conversations, in order to improve care for older adults who are living with chronic kidney disease?

Keren: That’s a very good and big question.

Alex: You don’t have to have all the answers.

Eric: In 30 seconds.

Alex: Right. Yeah. In 30 seconds. Right.

Keren: I think if I were to really emphasize two points, I think it would be … the first is really around transparency of options and presenting all of the available options to patients and really letting them think about which ones align best with their goals. People have different goals, as we all do, but really understanding and presenting these options in a way that patients can understand what the implications are for their day to day lives and their ability to kind of complete their bucket list. I think that’s the most important one.

Eric: For that one, do you see a difference between providers who have been doing this for a long time, dialysis providers, versus kidney doctors who just came out of training? Are you seeing culture changing?

Keren: I think we are in general. Not as much as I would hope. I thought that we would see a lot more of that. We see some of it in some of the younger providers that we’ve talked to. Actually some of these older providers who have been practicing for a while who have reflected on these experiences of moral distress, I think are really the biggest advocates for patient autonomy and decision making. One of my favorite quotes from the paper and from these interviews was this older nephrologist who said, “I have become more respectful of the notion that a few more days or a few more months might be meaningful to people. It hasn’t made me more eager to do intrusive and painful things to frail old people, but it makes me feel less guilty and less passionate and less angry when they demand it.” I think that’s, for people who ultimately choose dialysis against advice, but I think the reverse is also true. That kind of if you think about these salient experiences when things haven’t gone right and you realize that maybe you don’t have all of the answers and you need to really talk to the patients more about which option best suits them. I think that’s where things go best.

Alex: Right.

Keren: Then payment reform. I think that’s the other big key. You guys have signaled …

Eric: What type of payment reform? Do you have an idea of what it could be?

Keren: I think more clearly designating what is involved in conservative management and setting up a payment model for that, which would include multi-disciplinary teams and palliative care, would be really helpful for nephrologists, I think even in just thinking about their approach to older adults.

Alex: Part of the problem there is the nephrologist has to be involved. It seems like there should be pressure brought to bear on sort of both fronts. On the one hand, we need to have options other than dialysis. We need to have a robust system of conservative management. We need to have teams, as you say, providing inter-disciplinary care for people and some sort of mechanism to support that financially. On the other hand, we also need, I think we also probably need pushback on the tremendous money making industry of dialysis in the United States, and that kickbacks to doctors, et cetera, who can just make a tremendous amount of money rounding in these centers. If you still have that tremendous financial incentive to dialyze your patients, I worry that the answer shouldn’t just be that we give them … we’d also give then financial incentive for conservative management. We also need to address the scope of the profit motive in choosing the dialysis option.

Keren: Yeah. I agree with that. I think that’s very important to keep in mind kind of as we think about how to shape this option in the future.

Eric: Thanks, Alex. We just lost our sponsor, DaVita.

Alex: Damn it.

Keren: You know, there’s room for everyone. I think it’s about viewing the patients more holistically. You know, I think these were debates that were happening with dialysis companies a while back with respect to referral to transplant. Not to say that that’s been perfected, but I think it’s improved with CMS’ mandate to include transplant education and all of these things. I think that there’s hope, but change is needed.

Eric: It also sounds, from a palliative care and geriatrics perspective, there’s a lot that we can do on our end. Just looking at what the nephrologists are saying is that they feel like they’re alone and they can’t do this just by themselves, especially around conservative management. You said many described a need for palliative care consults. I think that’s something that we can do better as a field, is actually start working with our colleagues in nephrology to be more involved in these individuals’ care.

Keren: Yeah. I totally wholeheartedly support that. I think that would be really helpful. Even just thinking about is dialysis the only way to manage some of these symptoms? A lot of nephrologists kind of describe it as a way to palliate some of the symptoms that patients are feeling, but there must be other ways to do that as well.

Eric: Yeah. It’s fascinating too. Some of the symptoms may actually not be improved with dialysis or their function may not be improved, especially in older nursing home patients. A good study on actually function doesn’t significantly improve post-dialysis.

Alex: Right. [crosstalk, 00:30:40]. From Stanford. Nice New England Journal paper.

Keren: Yeah.

Alex: We should wrap it up. Is there anything else you wanted to say today?

Keren: No. I think that this is a ripe area for a lot of good collaborative work: palliative care, geriatrics, nephrology, social work. It’s a growing population in need, so I’m glad to see a lot of good work in this area.

Eric: What’s next for you?

Keren: What’s next for me? Summer vacation. We’re starting actually, we have a large multi-site trial, the decision aid, a patient facing decision aid geared towards older adults to help them navigate these choices. We are in our, let’s see, second or third month of this three year trial. We’re hoping to see if we can help patients and their care partners choose options that better align with their values and their preferences.

Eric: That’s great.

Keren: Yeah.

Eric: Is that decision aid available? Probably not yet, right? After the study?

Keren: Yeah. It’s in the last stages, but it will be available on our lab website. I’ll send it to you guys. Also, from the National Kidney Foundation.

Alex: Terrific.

Eric: Wonderful. Thank you again for joining us.

Alex: Thank you so much, Keren.

Eric: Alex, do you want to send us off with more of a song?

Alex: Yes, if you join me for part of this. [Singing].

Alex: Yeah. There we go.

Eric: Well, I want to thank all of our listeners. We will look forward to seeing you next week.