Recently, Zaldy Tan MD wrote a thoughtful article in JAMA (The “Right” to Fall, JAMA. 2010;303(23):2333-2334) regarding the autonomy of elders and the tension we often face in the geripal world between doing right for the patient and preserving the rights of the patient. I’m sure many of us have experienced this and have repeatedly discussed in team and with families whether there is “anything we can do” to help the patient who is surely a slow-motion train wreck waiting to happen. Unlike Wall Street banks, we allow patients to decide to “fail” on a regular basis: she doesn’t want more help, doesn’t want to consider moving to a higher level of care, doesn’t want to have that test/procedure/ medication/(fill in the blank), and HAS capacity, however limited, to make her own decisions even when those decisions may result in injuries or hospitalizations.

Dr. Tan writes of the impact the patient’s decisions have on her aging daughter and on the treatment teams and concludes that “I would explain again that no matter how misguided, older patients are entitled to make their own decisions. I would espouse the ethical principle of autonomy….” Most of us were likely trained within the boundaries of 20th and 21st century western biomedical cultural constructs and would presumably agree with these statements. But what if Carla, the patient’s daughter in the article, were also your patient? What if autonomy were not solely viewed as an individual’s right but as a concept that needed to be considered within the context of the person’s community, relationships, or interdependencies? The concept of “relational autonomy” is not new and I am not advocating that we move towards allowing the societal “greater good” to dictate medical decision making for individuals; history is littered with terrible examples of what can happen when we allow that to happen. But, while we can and do use individual autonomy as the principle that enables us to ethically step back and however regretfully watch the train go off the cliff, the emphasis on individual autonomy may also give us, in some sense, the right to fail families and caregivers, and perhaps even the patient herself.

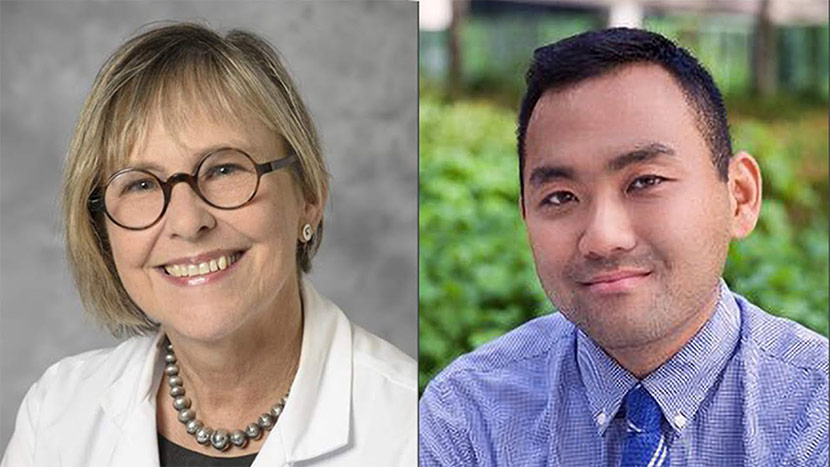

by: Helen Chen, MD