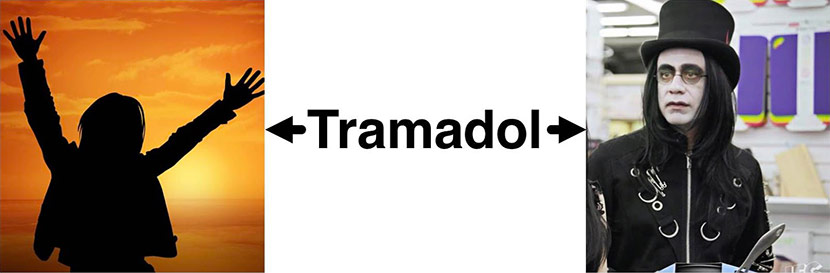

Tramadol. Is it just a misunderstood opioid that is finally seeing its well deserved day in the sun, or is it, as our podcast guest David Juurlink put it, what would happen if “codeine and Prozac had a baby, and that baby grew into a sullen, unpredictable teenager who wore only black and sometimes kicked puppies and set fires”?

Well that’s what we are going to be discussing today with none other than David Juurlink, an Internist and Clinical Pharmacologist at the University of Toronto who has written about Tramadon’t on both his twitter account and on the blog “Tox and Hound.“

David walks us through the top reasons why we should question the rapid uptick in Tramadol prescriptions, including that its metabolism is hugely variable, so giving a dose of Tramadol is like giving venlafaxine and morphine in an unknown ratio. It also is associated with increased risks of hypoglycemia, seizures, serotonin syndrome and all the other usual stuff with opioids (including dependence, addiction, and death).

So take a listen and comment below. We’d love your thoughts on Tramadon’t.

Eric: Welcome to the GeriPal podcast. This is Eric Widera.

Alex: This is Alex Smith.

Eric: And Alex who do we have with us on our podcast?

Alex: Today we have Professor David Juurlink who is an Internist and Clinical Pharmacologist at the University of Toronto who has written about Tramadon’t.

Eric: Tramadon’t.

Alex: Tramado, Tramadon’t. Welcome to the GeriPal podcast.

David: How you doing?

Eric: Wonderful.

Alex: Good.

Eric: So before we go into Tramadon’t which sounds like maybe a new version of Tramadol, we always ask all of our guests to give Alex a song to play. Do you have a song for Alex?

David: Yeah, I’ll pick, “You Can Close Your Eyes,” by James Taylor.

Alex: Terrific. [Singing]

David: Very nice. I’ve heard James Taylor play that song about a dozen times live and I wouldn’t pay money to see you but it was pretty good.

Alex: Yeah that was okay. I think I played it better at the memorial service we had recently. We had three part harmony because the accompanying vocals were terrific.

Eric: James Taylor has nothing on you, Alex.

Alex: Right. I think James Taylor might be the most requested artist on the GeriPal podcast and I don’t know whether that says something about the type of people we have on the podcast or whether…

David: Older people.

Alex: Right.

David: I’m actually seeing him in Tanglewood this July. My wife is taking me there for a birthday gift so looking forward to it.

Alex: What a terrific venue.

David: Yeah.

Eric: So again, thanks for joining us on this podcast. I’d just like to start off is that you write for a blog and you’re also on Twitter and I gotta ask the question, Tox and Hound, that’s the Twitter handle here. What does that refer to?

David: So Tox and the Hound is a blog, just started up a few months ago, it’s run primarily by Dan Rusyniak and Howard Geller, Toxicologists in New York. Did I say Geller, I meant Greller. Anyway there’s a group of toxicologists in Canada and the US, I’m one of them, maybe a dozen or so of us and we just write on a variety of topics. We publish it every week on Monday and they’re up to around 1,100 or so followers now and they’ve got a lot of people following, reading their stuff. We can just talk about whatever we want and my first post a few weeks ago was on Tramadol, but some very instructive posts up there.

Eric: And I also notice that on your Twitter page which is @ToxandHound there’s actually a picture of the Hound from Game of Thrones. So is the Hound like a Games of Throne reference or is it..?

David: I think they were just looking for some catchy title and so for each of the people who post a blog we have pictures of our dogs. I guess that we’re just dog people more than cat people. My dog happens to be wearing a wedding dress which is kinda funny.

Alex: I saw that.

David: It’s all in good fun.

Alex: So let’s get into talking about Tramadol here. I’m not sure how to lead in with this because there’s so much to talk about in this post.

Eric: How about just start us off, like what got you interested out of all the drugs out there your first post is on Tramadol, like why Tramadol?

David: Well, that’s a good question. I guess I’ve been thinking about Tramadol a lot for the better part of the last five years in part because it kinda burns me that in Canada, at least, and in fact it was this case in the US until a few years ago, in Canada it’s not a controlled substance and that bothers me because it’s perceived as somehow safer than things like Codeine or Morphine and what not. And I’ve had patients come under my care who have been on Tramadol and had problems with Tramadol and it is very clear from talking to them and their physicians, that it’s scheduling in Canada which is no different than Atorvastatin or Glyburide. It’s part of the reason why docs perceive it to be safer and there is just no case to be made that it’s safer than traditional opioids. In the blog post I unpack it’s pharmacology and my concerns about it but I guess the reason I singled it out was because I’m irritated by it’s scheduling which by the way I think, I don’t know if you have Australian followers, I think it’s the same situation there, not a scheduled drug.

Alex: And in the US is it a scheduled drug?

David: I think it is. So I think, I wanna say 2014 or so it was added to schedule 4, I don’t that makes since. I think Codeine is three but the fact is that just being a scheduled drug helps, I think, providers realize … If you have an analgesic that’s not scheduled and one that is scheduled, you’re probably gonna to the one that’s not scheduled if for no other reason than you perceive it to be somehow safer or devoid of some of the problems we encounter with traditional opioids. So that happened a couple of years ago in the US.

Eric: Yeah but we still see it here where people feel like Tramadol is a safer drug, that it doesn’t have this same bad side effects.

Alex: I was taught this in my Palliative of Care Fellowship, it was like, “If we wanna spare them opioids maybe we should think about Tramadol.” And then I started to teach my trainees when I was an attending the exact thing.

Eric: So we can all blame this on Alex.

Alex: That’s right, I started this epidemic of Tramadol.

David: Yeah, so I think that comes in part from the fact that it is different because, and we could talk about this in a bit, but it does have these dual mechanisms of action and that’s a fair claim but there are, I see it in Canada at least, I see pockets of prescribers in Ottawa and in London Ontario and few other parts of the province where there just seems to be a lot Tramadol use. I think it’s just people emulating what their colleagues are doing or following the advice of a key opinion leader and it’s not that it can’t help some people, like really it can do that but it’s pharmacology is not inherently rational and that’s why I try to discourage it’s use.

Eric: Well tell us a little bit about, what is the pharmacology here?

David: All right, so Tramadol itself, the drug Tramadol isn’t much of an opioid. It’s an SNRI, more or less like Venlafaxine. It’s converted by the liver into an opioid. It’s actually got several metabolites but there’s a key one, goes by the handle M1 or O-Desmethyltramadol and that metabolite is an opioid. So you have Tramadol, the SNRI, and the metabolite, an opioid. And the first problem that arises is that the conversion of Tramadol to it’s metabolite is effected by one of these CYP enzymes in the liver, CYP2D6. It’s the same enzyme that turns codeine into morphine and I think most people appreciate now that codeine isn’t an analgesic until it’s turned into morphine and that conversion, the 2D6 enzyme based conversion varies tremendously from person to person. It’s subject to a high degree of polymorphism and so depending where you’re from, six or seven percent of people don’t have any CYP2D6 and they won’t turn codeine into morphine, they won’t turn Tramadol into M1 and when you give somebody who’s a slow 2D6, you give them Tramadol, you’re giving them all SNRI and no opioids.

On the other end of the spectrum you get people with overactive CYP2D6, multiple copies of the gene. They’re typically from the Middle East or from Eastern Africa where this is quite prevalent and they’ll turn Tramadol into M1 like nobody’s business. And so all this is to say that when you give somebody Tramadol what you’re really giving them is this, you’re giving them like Venlafaxine and Morphine in an unknown ratio. In the individual patient level experiment that is analgesia this very kinetic issue introduces unnecessary noise.

Alex: So you have this terrific line in this post, “I like to think of Tramadol as what would happen if Codeine and Prozac had a baby and that baby grew into a sullen unpredictable teenager,” sounds like my teenager, “who wore only black and sometimes kick puppies and set fires.”

David: Yeah, I quite like that line. It came to me just before I submitted the post. It’s a little bit of hyperbole but it’s really just meant make people appreciate that there’s a lot of complexity to this drug that I think isn’t appreciated.

Alex: You just mentioned that there is a concentration of people who have more active or more copies of this particular gene or enzyme that metabolizes Tramadol into the active opioid in the Middle East and I think you also noted in your post that there appears to be more of an epidemic of Tramadol in that region of the world. I wonder if you could say more about use of Tramadol worldwide?

David: Yeah, so in India and I think also in China there are these generic companies that produce a massive amount of Tramadol and they ship it out to parts of the world where opioids are often quite hard to get. In fact you’ll read quite a lot now about the lack of access that physicians have, especially for palliative care, in parts of the world that aren’t especially affluent, like I think in Africa in particular and maybe in the Indian subcontinent it might be kind of hard to get your hands on Morphine for somebody at the end of life or some other opioid that we might not think twice about using. But Tramadol I think fills a void there and I don’t think the … So Tramadol’s very heavily misused in the Middle East and throughout Africa. I don’t think it’s exclusively that the genetics of the population, that’s gotta play a role, I think it’s more just the sheer availability. I tweeted a thread maybe a year ago on Tramadol, a ten or eleven piece thread on the same stuff I unpacked on the blog and I overnight got about 200 followers from Nigeria. I think part of the reason it’s such a problem in Africa is you just buy it, you don’t need a prescription you just kinda get it from

anywhere and it sounds like they’re huge swaths of the population in Africa and the Middle East that are physically dependent on and in many instances addicted to the stuff.

Eric: So, when I went through training, the idea of Tramadol was is that, oh it’s great, you have your SNRI, your Venlafaxine, you have your opioid, you combine them together, it’s two drugs for the price of one. You’re hitting multiple receptors and maybe helps with neuropathic pain, maybe it helps with a Mu opioid. Isn’t this great. It sounds like you’re saying, maybe it’s not so great.

David: Well yeah, no that’s … I mean there is truth to the fact that SRNI’s can have analgesic effects because the dorsal horn of the spinal cord involves serotonin transmission and obviously opioids can. So the party line, “Tramadol’s a good drug ’cause it has these dual mechanism of action,” is superficially appealing but if you just leave it there you’ve missed the point that you really have no idea how much of these various components you’re giving a person and you’ve got no assurances at all that you’re giving the person any opioid. So it just seems to me if you wanna give somebody an opioid, give them an opioid and if you wanna give them an SNRI, give them an SNRI. But don’t give them an SNRI that is converted in a highly unpredictable fashion to an opioid oh and, by the way, is encumbered by a whole bunch of other toxicities.

I make the same point, I gotta say, about Codeine too but we’re all comfortable with Codeine, right? But the fact is when you give somebody 60 of Codeine you are giving that person an unknown amount of Morphine and it is inherently irrational. Tramadol is the same way except Tramadol’s even worse because the parent compound has toxicities that Codeine doesn’t really have.

Eric: So it sounds like it’s a bad Mu opioid. Is Tramadol also a bad SRNI? Like how does it compare to effectiveness compared to let’s say Venlafaxine?

David: Well no, it is an SNRI and if you happen to have the genetic machinery to turn it into M1, it is an opioid but the problem isn’t that … M1’s a decent opioid and Tramadol is a decent inhibitor of the reuptake of Serotonin and Epinephrine. The problem is that the kinetics of the conversion just lends so much unpredictability to the experiment, that’s the crux my concern with the drug.

Alex: Right, you would never give somebody … Let’s say you were giving somebody a mix of Acetaminophen and Oxycodone, right? And say, “I’m gonna prescribe you an unknown mix of these two drugs,” right?

David: Yeah.

Alex: “Were just gonna give a mystery mix. Here you go. There might be a lot of Acetaminophen, there might be a lot of Oxycodone. I don’t know which. We won’t know, we’ll just give it to you.”

Eric: It’s a surprise.

Alex: Let’s see what happens. You would never do that, that just makes no sense.

David: Exactly. To be fair, I think that when you were taught or when you taught people that Tramadol was an effective therapy and I think I have to make this point, it is true that in some people Tramadol can do what we want but we don’t know how the patient’s gonna respond until we try it and given the high prevalence of the polymorphism to 2D6 and the other various ancillary toxicities, I think it’s really hard to justify starting a patient on Tramadol when we have other options that are more predictable.

Eric: Are there other things we should worry about with Tramadol?

David: Oh yeah. So the kinetics is one thing, seizures is another and again, this is dose dependent and I think it primary reflects the parent compound Tramadol, might be more likely in people who are slow 2D6’s or people who take more of it but seizures can occur, Serotonin toxicity can occur. I think this is actually pretty rare but there are some pretty compelling case reports of people who are on Citalopram and Tramadol and they have just obvious Serotonin toxicity happening within hours of starting one or the other drugs. The 2D6 thing is important for another reason. Let’s just say, let’s say that you’re on Tramadol, you’re taking a 150 a day and you’re doing well and you’re converting some of it into the M1 metabolite. If I came along and put you on a CYP2D6 inhibiting drug like Buprenorphine or Paroxetine or Haloperidol or Amiodarone, there’s a long list of them, what I would effectively do is turn you into a poor metabolizer and so that would have the effect or at least in theory could trigger something that looks like opioid withdrawal. You’ve been getting a lot of M1 for who knows how long because you were turning Tramadol into M1 and I come along with a new drug that turns off 2D6 and suddenly you don’t have any M1 and then you would be expected to display all the features of opioid withdrawal.

There are some other things, hypoglycemia, physical dependence is a huge issue. I did a tremendous anecdote of a guy I saw a while ago, he had a bad shoulder and he saw an orthopod who wanted to put him on Percocet and the guy said, “No thank you. I don’t wanna be on opioids.” So the orthopod said, “Well here’s some Tramadol.” So away he goes on Tramadol and does okay. About a year and half into it he wanted to come off of it and when he went from 150 down to 100 he was crippled with insomnia and he just tried and tried and could not manage to come down on the dose. He wasn’t addicted but he was physically dependent and it took a major toll on his quality of life.

Eric: So can I ask about the hypoglycemia? So big study came out in JAMA IM in 2014 making this link between Tramadol and hypoglycemia even in non-diabetics. How does that work?

David: Good question. I wrote the accompanying commentary with Louis Nelson on that and we scratched our heads and we have no clue what the mechanism is. When you dig into the literature … So first of all, I think it involves Tramadol the parent compound. There are similar reports, by the way, with Venlafaxine. If you look at the structures of Tramadol and Venlafaxine side by side, there’s more than a passing resemblance but the literature on this is very, very thin and it seems to involve a combination of either increased peripheral glucose uptake or reduced hepatic gluconeogenesis but as soon as you say those things people’s eyes start to glaze over and like I just don’t know. Maybe one day I will, maybe someone will listen to this podcast and they’ll tweet at me and educate me. I’m not sure but it happens, I think it’s a rarity but it’s one more reason, one more reason to be thinking twice and if you’ve got a patient on Tramadol who’s seizing, is it the Tramadol or is it the sugar in their boots.

Alex: So let’s bring it home, a bottom line for our clinical audience who are primarily practicing geriatricians, palliative care providers, doctors and nurses who are seeing older adults with multi-morbidity often on multiple medications, some with chronic pain or patients who are seriously ill nearing the end of their lives. In that context is there any role for Tramadol?

David: Different people will give you different answers. I think the answer is no and I’ll summarize why I think that is. When you put a patient on an analgesic whether it’s an opioid or an NSAID or acetaminophen or a cannabinoid or whatever, you aren’t just trying to relieve pain, what you’re trying to do, like all drugs have side effects and benefits, what you’re trying to do is to afford the patient more benefits than harms and of course pain relief is part of the benefits as is improved function and quality of life and what not. But into that experiment, the unusual and highly unpredictable kinetics with Tramadol and all of these other side effects that accompany even standard doses, it introduces unnecessary noise and unnecessary toxicities. It’s not that it can’t work, it’s that when you start it you are really rolling the dice and given that we have so many other alternatives that are less unpredictable it doesn’t seem, to me, it doesn’t seem sensible to roll those dice.

The only time I prescribe Tramadol is when I’ve got a patient who comes in on it and they are doing okay and I’m not gonna rock the boat by changing things but I would universally discourage my colleagues and my house staff from starting them.

Eric: So you wrote this post on the blog, you tweeted about it, did you get any hostile reactions from people who strongly disagree?

David: Oh yeah, yeah, of course. Whenever I’m … I’m quite critical of opioids generally. I prescribe them at end of life all the time and I prescribe them for acute pain and I do prescribe them for chronic pain, although I do so differently than I did five years ago. Maybe we could talk about that on another podcast ’cause that’s even a bigger deal. But when you criticize opioids or you criticize cannabinoids for that matter, this has happened to me on the cannabis front, you invariably encounter people who hold different opinions and most of the disagreement is, at least with Tramadol, is polite and it comes from other professionals but when I reduce it down to what the crux of the disagreement is, the disagreement is, “Well I’ve used it and it works.” My point is that sure it can work but if you think about the drug’s pharmacology a little bit which you aren’t really asking all that much ’cause it is a drug and we should think about the pharmacology of the drugs we prescribe, it does not make sense full stop. It’s not that it can’t help some people, it’s not that it can’t do what we’re trying to do and afford more benefits than harms, it’s just that the initiation of Tramadol is it’s open season on your patient when it comes to side effects and benefits and that’s kind of what it boils down to.

Alex: That’s terrific. I wanna ask a somewhat tangential question. Your post on twitter, your tweet went crazy. That entire thread, there are multiple components of it that have been retweeted multiple, multiple times and picked up by a number of people.

David: This is thread on Tramadol?

Alex: Yeah, the thread on Tramadol, it’s just incredible. We’ll link to it in the podcast that accompanies this or the post that accompanies this podcast. But I wonder if you could say a little more about … One of the things that Eric and I are often asked to give talks about is use of social media and medicine. Something about the role of Twitter in disseminating this message and how you decide to use this thread method of disseminating this message.

David: I didn’t see that question coming but it’s a good one. So like you guys, I publish things and I guess I could have got into Twitter maybe five or six years ago. It has pros and cons, it can be a bit of a time sink if you’re not careful but it became apparent to me that, especially as you accrue followers, that it’s a better way of reaching people. I can publish a paper, in fact I’ve written about Tramadol a couple of times and I’m sure that those publications have been read by somebody but I don’t just want an extra pub net hit, I don’t just want an extra line on my CV, what I care about … I’m mid career now. What I care more about is influencing how people think about drugs and so I think that the reach of Twitter is just far greater than most journals. We even had a piece in New England maybe a year and a half ago on opioids and I had a Twitter thread about that that also got a lot of attention. I think it probably honestly got more reading than the actual publication in the journal.

So I think that the thread approach provided you don’t overdo it, I see people who write these threads that go on for 30 or 40 or 50 different tweets that are all like together, it’s a matter of personal taste, I find that a bit tiresome. This Tramadol thread I probably spent about three hours putting it together and yeah it did get, let me just see…

Eric: Three thousand retweets.

Alex: Three thousand retweets.

Eric: Two hundred and thirty four comments today.

David: I’m just looking at the analytics now. So the engagements, 555,000 impressions, 50,000 engagements. So I don’t know how many people are gonna take stuff away from this but if they take nothing else … Can I make some political comment?

Alex: Please.

David: Where was it? I think I ended up on my thread, I linked to a … tweet number 13 I made the point, “Anyways those are some of the problems with Tramadol. Here’s an analogy to simplify things.” And then I linked to a tweet after I’d given a talk to a bunch of med students at the University of Toronto and this will probably get me in trouble with some of your listeners but I said that tweet was, “Just told 200 medical students Tramadol is the Donald Trump of pain medicine, dangerous, irrational and you’re going to regret it.” I can say that ’cause I don’t work in the US, probably denied entry next time I try and come. But the whole point of it is that if some medical student out there or some resident or some faculty doesn’t remember 2D6 and all that stuff, if they just remember that one little joke about Tramadol being unpredictable and irrational and dangerous, I’ve accomplished what I’ve wanted. Maybe somebody out there will choose not to prescribe it because of something I wrote on twitter a couple years ago.

Eric: Well I would love to say we want to have you, invite you to come in person to one of our podcasts but I think that’s no longer an option ’cause you’ll be denied at the border.

David: Yeah, I’m North of the border now.

Eric: They’ll build a second border wall north of us now.

David: Well Canada’s not paying for that I’m pretty sure.

Eric: Well before we end, is there anything else that you think we haven’t talked about that you think is important to talk about?

David: No, nothing. I think we covered all the bases. I think we did importantly touch on … I guess I should back up a little bit. You asked if I get any brush back. I have had a couple of unpleasant interactions with patients, not interactions that I’ve engaged in but people who’ve said, “Don’t tell me that Tramadol can’t work you pointy headed pharmacologist.” There’s no point debating those things but I think I do want to make clear that it’s not that we shouldn’t just be taking everyone’s Tramadol away. It can sometimes help people and I think it’s a point that needs to be made. My concern with it is that it’s the initiation of it and the uncertainties that accompany that. There are all kinds of people who are on Tramadol and actually are doing okay, I think. Although that’s a separate issue in and of itself because, and I guess this is the last point I’ll make and it relates to all opioids and it’s a dose dependent thing, I am convinced that there’s a huge swath of the chronic pain population out there who are on opioids, on high doses, they’re on maybe a 150 or 200 Tramadol or they’re on 2 or 300 of Morphine equivalents of something else and they and their physicians are very often convinced of the benefit of the opioid therapy long term and I think that is at least partly obfuscated by the phenomenon of dependence and withdrawal.

If you say that to a patient, well how do you know? There’s no data to suggest this, you’ve got this anecdote. You’ve been on 500 of Morphine equivalents for the last few years. How do you know that it’s helping you? Well the answer is usually, without it I’m not doing very well. That is obviously withdrawal and the symptoms that accompany withdrawal have to be obfuscating the overall assessment of benefits versus harms and so that’s happened with Tramadol, it’s happened also happens a lot more with Fentanyl and Oxycodone.

Alex: Now often when we go after medication, there’s often behind the medication there’s often some other power, right? Big pharma making a lot of money, behind the scenes pulling the levers, pushing the medication. Is that true for Tramadol?

David: Yes. Tramadol, I don’t quite have a handle on sales figures but it’s a very popular drug in even Canada. Here’s an example of exactly that phenomenon. In 2007 Health Canada announced that they were going to consider putting Tramadol on our schedules for controlled substances which it’s pharmacology demand, there’s no, we’ve talked about this, there is no reasonable basis to have it on the same schedule as Atorvastatin. When they made the announcement they were very quickly lobbied by Purdue Pharma and by I think Janssen and by a palliative care organization coincidentally that received funding from at least one of those companies. They decided, Health Canada in its wisdom decided not to schedule Tramadol and now 11 years later it’s still not a scheduled substance, it’s still being given to people by orthopedic surgeons or other physicians who don’t view it as an opioid in part because of its classification. So that is one example of how lobbying on the part of industry or groups that are funded by industry influences what happens out in the real world. It’s just one small example but companies are in business to make money. They make money by selling pills and it’s understandable that they would oppose measures to curtail the use of the pill.

Eric: Well again, I wanna thank you for joining us today.

Alex: Thank you so much David.

Eric: I learned a ton.

David: My pleasure.

Alex: It was terrific and this was fun.

Eric: How about before we leave, Alex, you wanna finish off with a little bit more of that song?

Alex: I’ll keep working on it and maybe someday it will be worth paying for.

David: You never know. Hey, thanks guys.

Alex: [Singing]

Thanks David.

Eric: Thanks David.

David: All right, thanks guys. That was fun.

Eric: Well thanks again for joining us and thank you to all our listeners. We look forward to talking with you next week.