There is a lively debate going on in academic circles about the value of Advance Care Planning (ACP). It’s not a new debate but has gathered steam at least in palliative care circles since Sean Morrisons published a JPM article titled “Advance Directives/Care Planning: Clear, Simple, and Wrong.” Since then there has been a lot of back and forth, with even a couple of podcasts from us, several JAMA viewpoints, and most recently a series of published replies from leaders in the field on why ACP is still valuable (see below for references).

Despite all of these publications, I’m still left at a loss of what to think about it all. Most of the debate seems rather wonky, as honestly it feels like we are getting stuck in the weeds of semantics and definitions, like what counts as ACP versus in the moment decisions. But the consequences are real, from research funding dollars to health systems investment.

So in today’s podcast, we have invited Juliet Jacobsen and Rachelle Bernacki to talk about what all the fuss is about. Juliet and Rachelle are two of the authors of a recent JAMA viewpoint titled “Shifting to Serious Illness Communication.”

We discuss the debate, how to think about definitions of ACP vs serious illness communication, what should go into high quality conversations, the evidence for and against any of this, and ultimately where we go from here.

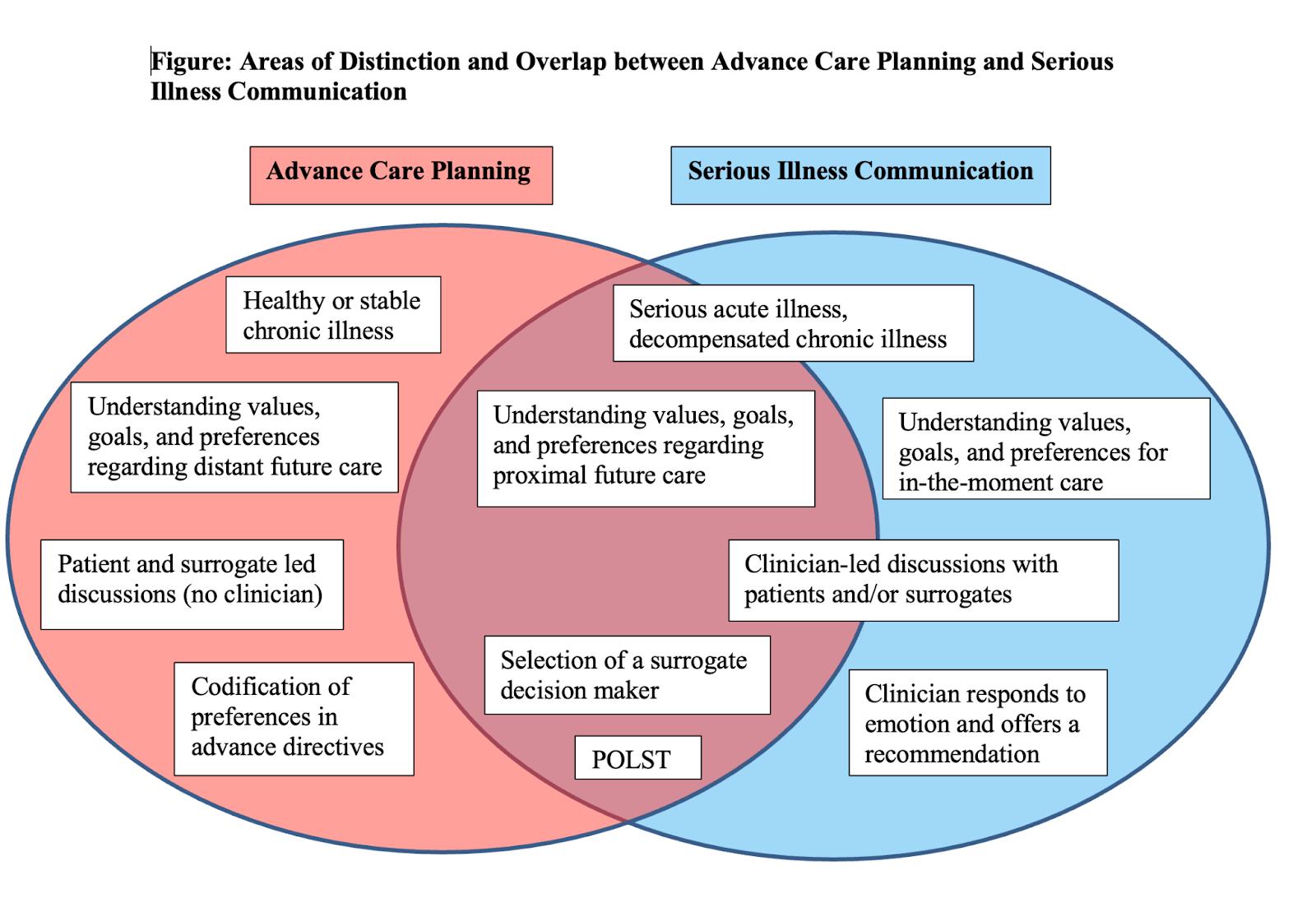

Also see the image below from Alex’s editorial in JAGS, a Venn diagram of advance care planning and serious illness communication.

So check out the podcast and if you are interested in diving into this debate, here are some great links to learn more:

- What’s Wrong With Advance Care Planning? JAMA 2021

- Controversies About Advance Care Planning. JAMA 2022 (a reply to the above)

- Shifting to Serious Illness Communication. JAMA 2022

- Our podcast with Sean Morrison titled “Advance Care Planning is Wrong”

- Our podcast with Rebecca Sudore and Ryan McMahan titled “Advance Care Planning is So Right”

- Our podcast with Rachelle Bernacki and Jo Paladino on the Serious Illness Conversation Guide

Eric: Welcome to the GeriPal podcast. This is Eric Widera.

Alex: This is Alex Smith.

Eric: And Alex, who do we have with us today?

Alex: We are delighted to welcome Juliet Jacobsen. Juliet and I were co-fellows together at Dana-Farber and the Brigham way back in the day. Delighted to have you on our podcast. Juliet is a palliative care clinician and she’s on sabbatical in Lund, Sweden. Welcome to the GeriPal Podcast.

Juliet: Thank you.

Alex: And we’re delighted to welcome back, a frequent guest to our podcast, Rachelle Bernacki, who’s a palliative care physician and geriatrician at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Welcome back to GeriPal, Rachelle.

Rachelle: Thank you. I’m delighted to be here.

Eric: So we’re going to be talking about serious illness communication, about how it differs or not from things like advance care planning. What is it? What’s the process? Lots of great stuff, including a lot of this coming out of both of their papers from JAMA that was published recently, which we’ll have a link to on our show notes. But before we dive into that paper and the topic, who has a song request for Alex?

Rachelle: I do. It’s The Weary Kind by Ryan Bingham from the movie, Crazy Heart.

Alex: Great film.

Eric: Why this song?

Rachelle: Well, so I had the great fortune of having COVID in January and I felt pretty lousy, actually. So I watched that movie for the first time and I loved it. It was a great movie. And I listened to the song and the lyrics, I thought, were really kind of indicative of what many people, I think, are going through in the hospital right now. And so, “This ain’t no place for the weary kind, no place to lose your mind. Ain’t no place to fall behind. Pick up your crazy heart and give it one more try.”

Rachelle: And from my standpoint, going through whatever number search this was, I was in the hospital and got COVID. And I ran into a nurse in the stairwell eating, because we don’t have any space to eat and she’s eating. And I just said something like, “Thank you for being here,” and she just burst into tears. And I just think all the people that are working right now, they’re really working from their heart and they’re tired.

Rachelle: And I don’t know if I want to use the word burnout, but this is also sort of ploy to get Vivek Murthy to come talk with you guys about this issue, because I think it’s really, really important. And I’m worried about all of us as healthcare workers, but particularly… And when I say particularly those in the hospital, because they are just tired. And I’m sending a big virtual hug to all of you and I wish I could talk to all of you in the stairwell and thank you for what you’re doing. Because it’s hard work right now and we’re tired and we just… We need a little boost.

Rachelle: So, this song gave me that. And actually, ironically, getting COVID gave me that. I actually just said, “I’m going to be sick,” and I didn’t go into work. And I didn’t actually even call into my meetings because I lost my voice along with my sense of smell and taste. And it was really good for my mental and physical… Physical health, obviously, but mental health really. So if you are sick, I really encourage you, just take the time off. The world will continue without you and you will feel better. It was amazing, two weeks at home and I really felt better. So, anyways. And I know you guys care about this issue, so that’s why I picked it.

Alex: Terrific story, Rachelle. And I’ll just note that Eric knows I invited Vivek Murthy, Surgeon General of the United States, yet again to be on our podcast. Vivek, if you’re listening, or if anybody’s listening who has personal connections, please reach out to Vivek and ask him to join our podcast. We would love to have you on. Great song choice. Here’s a little bit of The Weary Kind.

Alex: (Singing).

Eric: That was a lovely song, Rachelle.

Rachelle: Thank you.

Eric: So let’s get to the topic at hand. Both of you published a paper in JAMA, title of which is Shifting to Serious Illness Communication. And this seems like it’s part of this larger debate around… And some of our listeners may not know there is this debate going on around advance care planning. Like, should we be doing advance care planning? What’s the evidence behind it? Should we throw it out? Should we focus on something else, both from a clinical and a research perspective?

Eric: I’m wondering, Juliet, if you can give us a… For those who may not know about this questioning of advance care planning, can you give us a background of what’s been going on for the last…

Juliet: …40 years? [laughter]

Eric: Well, how about just with the debate?

Juliet: And I think it starts then, but I really think this is just a debate of how can we help? We see our patients and our families throughout the illness trajectory into the hospital. We see them struggle, right? We see how hard it is. We see when they don’t understand. We wonder if they were told. And I think the advanced planning debate is really a question of, how do we help this very complicated situation?

Juliet: And it started really maybe in the nineties with people saying, well, maybe if people had an advanced directive, right? Maybe if they just filled out this piece of paper, we knew what they wanted, we can measure that. If they had a healthcare agent, then this would be better, right? Because then we would know what they wanted when this hard stuff came.

Juliet: And so for a decade or two, people tried to measure these conversations with advanced directives, which was a very measurable process outcome, essentially. And so onto effects, right? There was no effect when people completed these advanced directives on outcomes.

Juliet: And then people like Rebecca Sudore started saying, “Well, maybe it’s not enough, right?” Maybe just filling out a piece of paper about who your decision makers aren’t enough. And maybe we should have more patient-centered conversations. What are your goals? What are your values? How do we include the people that you care about in these conversations? And so the definition of advance care planning really switched in, I think, 2017, 2018, there was kind of a United States definition and then an international consensus definition.

Juliet: And so what we were measuring now has changed, right? It’s no longer an advanced directive, it’s this kind of quality conversation. But still trying to think ahead, hypothetically, what do you want when you get sicker? And I think part of the struggle has been, it’s hard to know what you want when you get sicker. It’s hard for your family to know. It’s hard to know what the options are going to be. It’s hard to record that in our system, which is so complex, then you end up in an outside hospital somewhere.

Juliet: And so there’s all these systems issues that kind of interact with these important conversations and make it very, very difficult to measure outcomes. Which is, I think, that’s where we’re struggling, right? We want to do meaningful work and so we want to know that the conversations we have impact patient care. And it’s been hard to do that. Rachelle, do you want to add anything to that overview?

Rachelle: I think that’s right, Juliet. I think to some degree, are we talking about semantics? But I do think, when I think of advance care planning, I think of a iterative conversation that’s not just an advance directive. And I worry a little bit that we’ve kind of clouded the waters perhaps. And I hope… I actually think that Sean Morrison and Diane, they really intended for a good thing. They wanted this conversation to happen.

Eric: Just for our listeners, can you just give an overview? We did have Sean Morrison on our podcast about six months ago. And then we had Rebecca Sudore on our podcast.

Rachelle: Yes. So he wrote this paper, I have it printed right here, What’s Wrong With Advance Care Planning? And talked about several trials that ended up being… He would call them negative, I would call them null, some of them null. And he chose a couple like the ACTION trial, which was a Respecting Choices trial in Europe, which was negative. And I think a couple of the trials that he chose actually had issues with fidelity to the intervention. And a couple of the trials he chose, I worry a little bit. They were slightly mischaracterized. So one that the primary outcome was supposed to be documentation, which it improved documentation, it wasn’t powered to actually look at any utilization or hard outcomes. And they were secondary outcomes that were negative.

Rachelle: I just saw, I think yesterday, there was a nice group of responses and this has really hit a nerve with many people. One with Randy Curtis. He wrote a beautiful piece in JAMA talking about why it still matters to talk about advance care planning and used his own self, used his mother and his own self as examples of why it matters. But I think the other thing was that Susan Mitchell wrote a nice response talking about that maybe our current research systems of RCTs aren’t working well to research this topic, which I think is valid. And pointed out some of these inconsistencies with what was actually noted and concluded in some of the articles.

Rachelle: And just like Juliet said, Rebecca Sudore has done such incredible painstaking work, right? Painstaking work to go through each outcome and really characterize and document what works and what doesn’t. What’s the intervention? What’s the outcome? What did they see? And in her scoping review, she found that there’s largely, advance care planning had positive outcomes. And I think her response was well-stated in stating that she felt her review was mischaracterized a little bit. And I would agree with that.

Rachelle: And I think we’re… The other thing I worry about is, I think what we want to do is get the message across about what works, right? What do we know works and what are the open questions still? And maybe this is the right way to do it and maybe it’s not. I’m not sure.

Eric: Yeah.

Rachelle: I’m not sure.

Eric: So it sounds like, so when we think about advance care planning, it’s an iterative process that may result in documentation, like an advance directive, assigning somebody a surrogate through a durable power of attorney paperwork. Or like a POLST form or in the VA, we have a Life-Sustaining Treatment Initiative that we do. And then there… I’m going to go to your JAMA paper, which is Shifting towards Serious Illness Communication. What’s that and what’s the shift there?

Rachelle: Juliet, do you want to take that one?

Juliet: Sure. I think the shift is really maybe more deeply recognizing the process. That this is iterative from diagnosis to end-of-life, right? So it includes in-the-moment decision making, it includes the day before in-the-moment decision making, which I don’t know if that’s still advance care planning or if that’s… It’s this gray zone, right? When does advance care planning become decision making, right?

Juliet: Because even in the ICU, they’ll often have multiple meetings just to try and help a family move along before they can make a decision. Right? And so it’s this spectrum. And I think serious illness communication really tries to capture that spectrum of care, that we’re trying to have high-quality conversations with patients over a long period of time.

Eric: Yeah. It sounds like that doesn’t necessarily need to actually lead to a decision either. Is that right? So like part of, when I think about ICU conversations, is part of it may just be, we’re going to talk to them about how things are going. It may include delivery of bad news. It may include delivery of good news. But we’re going to have this forum for us to hear from family members, hear from patients, for them to hear from us. Is that right?

Juliet: One of the ways… I’m a big Harry Potter fan and there’s that scene at the end where he’s kind of walking to sacrifice himself to Voldemort, right. And so it’s really, the whole series is really about him accepting his own prognosis. And his parents show up, right, and they’re kind of walking with him for those final steps and until that end. And I kind of think our patients are on this longer journey, right? And there’s all these different people showing up, right?

Juliet: And it’s the oncologist walks a few steps and talks about the prognosis. And then the infusion nurse comes and she walks a few steps and she talks about what it was like to hear that prognosis. And then three weeks later, you’re in the emergency room and somebody else talks with you for a little while. And so it’s this deep process within a system of kind of accompaniment and kind of psychological support, right, for patients as they’re going through this illness.

Alex: I love the Harry Potter reference. Is it the first time that Harry Potter has been referenced on GeriPal?

Juliet: It’s the first time?

Eric: I couldn’t believe we didn’t reference it when Louise Walter was on, but…

Juliet: It’s a metaphor for our work, the whole series.

Alex: It is. It’s part of our family mythology. That’s for sure. That, and Lord of the Rings and Star Wars.

Juliet: There’s a lot in those. Yeah.

Eric: So I got a question. I really liked your JAMA paper because it also outlined steps for serious illness communications, which is really broken down into four simple, but very complex steps. So I was wondering if you can talk a little bit about what those steps are?

Rachelle: Sure. So it starts with assessing illness understanding. And so that, I think, is so key because it can make your discussion much more efficient, right? So if you ask people, what do you understand about your health or your illness, then you can… And you have to tease that out a little bit and assess whether they have a good understanding or perhaps not so good understanding.

Rachelle: Then the next step is really to give a prognosis that’s tailored to patient preferences. And one of the things that I’ve been thinking a lot about over the last few years is thinking about prognosis in a broader way. And thinking about prognosis, not necessarily in terms of time, but in terms of thinking about function. So a functional prognosis. So maybe not where I’m worried that you have months to a year to live, but I’m worried that you’re not going to be able to function as well, that you’re going to need someone to live with you, that you’ll need help going to the bathroom. Those kinds of things. And that kind of prognostic information can be just as valuable, really, to patients and their families planning as time-based information.

Rachelle: And I also think that it’s crucial that a interdisciplinary team participate in this happening. And I think social workers, advanced practitioners, nurses, really feel comfortable giving functional prognoses more so than time-based prognoses. And I’ve really learned that piece from working with interprofessional teams. So that’s the second step, is delivering a patient-centered prognosis.

Rachelle: The third step is finding out what their values and goals are. And I think that can be really hard. People don’t always know how to ask about values and goals. And one of the things that Juliet and I have talked about is that having some scripting or specific questions ahead of time can be really helpful. So you can ask, what’s your most important goal if time were short? But the other thing that can help you get at values and goals are things like trade-offs. Like, how much are you willing to go through for the possibility of more time? If you ask that question, you’re actually really digging at what someone’s values are because it asks you to weight things.

Rachelle: And then the last step, which I think is also a hard one, is making a recommendation. So I think so often, and at least when I went through training, the way we did these conversations is we sort of put out like this Chinese menu of options. “And you could do this and you could do that, and we’re here and we’ll do whatever you want.” Talking about analogies, we want to build a deck and we’re going to professionals and we actually want them to make a recommendation of what would look good on the deck. And they’re like, “Well, we can do whatever you want.” And we’re like, “We know that, but we don’t know what we want,” you know?

Rachelle: And so we told you what we’re aiming for. We want a good view of the pond, but we need a recommendation about what would work. And so I think making a recommendation is really crucial, but the important part of making a recommendation is first hearing what matters to the patients. You have to hear what they understand. You have to hear what their family understands, what they care about. And then you can make a medical recommendation that matches with what they’ve told you. And that skill is hard.

Eric: And I love that because I’ve seen people just make recommendations out of the blue. I got to say, it usually goes very bad. But in order to make a recommendation, like you said, you have to understand what’s important to them, what their values are, what they’re worried about. And before we can even assess what their values are, what’s important to them, it has to be in the context of what they’re dealing with here. Are we on the same page? And that’s where prognosis comes into play.

Eric: And I was like, when I talk to interns, “Would you be here in the hospital right now if you knew you had two weeks to live?” What’s important to you depends on that context about prognosis and illness understanding. So it’s very much kind of, you got to do the step before, before you do the next step. You can’t just jump ahead. And every time I do palliative care and I think I want to jump ahead, like somebody says, “Oh, so and so wants hospice. Can you just talk to him about hospice?” Inevitably, it’s always when I jump to hospice, they’re all, “Wait, what’s hospice? I’m healthy.” I always get myself into problems.

Rachelle: One of the things, they are definitely ordered steps, right? So you need to do them in order. And I think a lot of times when we get consulted, we’re asked for the outcome, right? We want to get the DNR, right? Get the hospice referral. But one of the things that I try to teach, because both Juliet and I have done a ton of teaching about this, is that if you follow these steps, that outcome sort of presents itself. Oftentimes, not always.

Rachelle: But the other thing that I like to model, and Juliet and I have both done this, is cases where there is no decision. And hospitalists in particular are like, “You just spent 15 minutes talking to the patient. There’s no decision.” And I’m like, “Yeah, how is that for you?” But I think what I’m trying to model is that we got some really valuable information, even though we have no decision.

Eric: Yeah. And like that too, because sometimes they hear, “Oh, don’t go into these conversations with a agenda.” We’re always going to have an agenda. Part of our agenda is to have a conversation, talk about prognosis or illness understanding or make a recommend… or figure out what’s important to them. But it’s really not, not having an agenda. It’s divorcing ourselves a little bit about the outcome. The outcome is dependent on the conversation.

Rachelle: Yeah. Yeah.

Eric: Yeah. And I wonder maybe, that’s where some of this debate around advance care planning is, especially if you create advance care planning with an outcome, like finishing an advance directive or a POLST form or some other life-sustaining treatment document. Which you don’t have to do on every single time. And then that’s why I also despise palliative care templates that have like, you have to do an advance care planning discussion in the first visit, because there’s no evidence for that from any palliative care trial.

Rachelle: Right. Totally agree.

Juliet: I guess I would just add, there’s an agenda and there’s expertise. And they’re similar and different, right? As an expert, I do have an opinion if you’re really symptomatic about where you might have the most comfortable death, right? And if you’re really symptomatic, I might have a really strong opinion about how to keep you safe. And I’m going to go in with my expertise and I’m going to try and both understand what you understand, what you know and want to know, what your values are. And then try and match that with my expertise, right?

Juliet: Because I don’t just wash my hands of my experience when I walk in the room and I don’t think people want to. It’s kind of like what Rachelle was getting to with the deck. So, I wonder if we just confuse those two ideas sometimes. We do walk in with expertise that I think people want.

Eric: So I got a question. Your definition of serious illness communication, those four steps, is also what I feel like. And when I hear, like when I talk to folks like Rebecca, what makes a good advance care planning conversation. How much of this current debate is just like semantics? What are we going to call this versus honestly very… Like something very different?

Juliet: It’s interesting. Because the ideas have been merging for years, right? And you have the VitalTalk talking map and then you have the Serious Illness Care Program and we’re merging towards these structures. And then the structures are also converging over time, right? EMAP came in there. And sometimes for fun, I’ve taught sessions where I just line them all up and I have the learner figure out what the deep pattern is, right. Because, I mean, it’s essentially the four steps, but I think it’s fun for people to realize that all of these are more the same than different.

Juliet: And I think maybe we got tricked a little bit with the word advanced, right? Like there’s this idea that it had to be done really early. And I don’t know. I think maybe that’s where we’re struggling with, is somewhat kind of, what’s the most effective timing for some of these conversations.

Alex: If I could share a figure. I’ve been struggling with this myself, like what is this difference between advance care planning and serious illness communication? How much distinction is there and how much overlap is there between these two concepts? So I created a Venn diagram for a JAGS editorial about a forthcoming article. A group out of Yale studied advance care planning and perceived risk of dementia. So I’m just going to share on my screen.

Alex: For those of you who are listening to the podcast, this would be an opportunity to check out our YouTube channel, so you can see there’s a Venn diagram. But I’m just going to describe it for you.

Eric: We’ll have a picture of this on the podcast show notes.

Alex: So we have one circle labeled advance care planning and the other, serious illness communication and they overlap about halfway. There are areas of distinction. So for example, when we’re thinking about advance care planning, thinking about patients who are healthy or have stable chronic illness. And that’s distinct, that’s not in the serious illness communication circle, because they don’t have serious illness.

Alex: When we are in the serious illness communication, we are thinking about patients with serious acute illness, something that came on suddenly or decompensated chronic illness. Though, I would argue-

Eric: Wait, Alex, I got a question on this. Where would, let’s say, something like dementia fit in? Is that a stable chronic illness or is that a serious illness?

Alex: Yes. I think the answer is yes. I think the answer is yes. And that’s part of the area of overlap. And that’s part of the issue at hand here, is that there’s this false dichotomy between advance care planning and serious illness communication that’s been created, where advance is way in advance, healthy or stable chronic illness. And serious illness is only in the moment when you are seriously ill and you have to make a decision right then, at that moment.

Alex: But I think that there’s a spectrum, as our guests were talking about here. And that both groups would claim dementia, right? Both people who study serious illness communication and advance care planning. And it can be appropriate in both. So advance care planning, I put like, understanding values, goals, and preferences regarding distant future care, that’s distinct. But understanding values and goals and preferences for in-the-moment care, that’s serious illness communication. But overlapping in both are like proximal future as we were talking about those ICU sorts of decisions.

Alex: And then in the advance care planning realm only, patient- and surrogate-led discussions, right, without a clinician. This is another distinction we haven’t talked about as much, but Rachelle and Juliet were talking about these serious illness conversation is clinician-led, right? These clinicians are leading these conversations. And that can be true of advance care planning conversations, but it’s not necessarily true of advance care planning conversations. Think about PREPARE For Your Care, which is patient-facing. They do this on their own.

Alex: And advance care planning, there’s often codification of preferences and advanced directives. Serious illness communication, there’s a greater emphasis on responding to emotion, offering a recommendation, key piece of those steps. And areas of overlap, selection of a surrogate decision-maker. I think both advance care planning and serious illness communication would claim that. Filling out forms like a POLST or a life-sustaining treatment.

Alex: So anyway, let’s beat up on this Venn diagram now. I’m sure there are plenty of faults and there are other areas in which I haven’t put on here because you only have so much space. What thoughts about this conceptual framework?

Eric: Juliet, take him down a notch.

Juliet: Yeah.

Rachelle: I can see Juliet’s wheels turning, yeah. I like this, Alex. I do think, one of the questions I have is, how much overlap? Is it like almost on top of each other or is it separate? I think this is probably pretty close to reality. I guess one of the things that I have always felt is that it’s important for someone on the team that’s integrated into the care team, having those discussions that can actually affect what happens to the patient.

Rachelle: And so I think it’s harder for someone outside the team. And in a lot of trials where we’ve seen people that kind of drop in for one visit or drop in, that’s really hard to see outcomes from an outside person where they just come in and do one intervention. And I worry about those kinds. I mean, I’m not saying that you could never see something from that, but I’m not sure. I think it’s much harder to impact care.

Alex: Yep. And I think we do want to talk about evidence for serious illness communication and next steps. We’ll get to that next. But before we do that, Juliet, any thoughts about this? How do you think about these two and how they’re related? Is it something like this?

Juliet: I think this is right. I think it’s tricky, because if you look in the literature, there’s this massive overlap. So a lot of the citations for Sean’s paper are patients with serious illness where advance care planning interventions didn’t work. Right? So, what do we call that, right? It’s just, there’s a lot of confounding of the terms.

Juliet: But I do think the important distinction is the difference between healthy and ill. Because you’re going to hear, to your point, Rachelle, the importance of prognostic information, you’re going to hear that information differently when you have an illness, when you can feel it in your body, and it’s going to change your thinking in a different way than if you’re healthy.

Eric: Okay. I got a question then for both of you, given Alex’s Venn diagram, seems like you can move the little circles around. So are you advocating in your paper that we should just shift to serious illness communication? Or is there a role still for advance care planning, if we’re going to keep them separate?

Rachelle: It’s a great question. I guess I’m going to probably do a podcast no-no, which is answer a different one. Which is, what I heard and agreed with in the Sean’s piece is that this tick-box method where we’re just putting in a dot phrase or we’re saying we did this, is not that meaningful. I’m not sure that… And one of my worries in paying for advance care planning, we have these 99497, is that we didn’t probably do enough of our homework to know what actually helped. Right?

Eric: Yeah.

Rachelle: And that maybe that whole… There should have been more demonstration projects or there should have been more work done to know what actually are the pieces that make a difference. And so, yeah, I guess… And I’m going to let Juliet answer the hard question.

Juliet: Well, so here with my Swedish colleagues, we’ve been starting to gather data with this days, months, and years framework. So the Swedes actually have kind of a national registry for things that happen, conversations that happen months before death and the conversations that happen years before death. And we could talk about kind of what those boundaries are, but it’s a way of thinking about the process and trying to quantify the process.

Juliet: In most of these advance care planning trials and I think this is true for the serious illness trial as well, people have an average of kind of one, 1.3 extra conversations. So it’s this kind of small improvement and we don’t even know if that’s years or months or days before… We don’t know where those are. And so I think we need to gather more data and then actually look to see, is there a dose effect that we can look at? Is there a timing effect that we can quantify to say what the right amount is?

Rachelle: Yeah.

Juliet: And it’s not that we don’t have outcomes. We should talk about outcomes because it’s not like it’s zero.

Eric: Tell me about the outcomes?

Juliet: So, in Sean’s paper, they are hardcore researchers. They’re looking at difficult outcomes, utilization outcomes, right? So ED visits, hospital days, admissions. So those are difficult with big structural interventions to change, let alone looking at a conversation to see if that makes a difference. Does watching a video impact utilization to that degree? I’m not that surprised that it didn’t.

Juliet: So we should think about the strength of the intervention and then the strength of the outcome we’re trying to impact with that intervention. There were lighter ones, which I think was disappointing that weren’t impacted. So the ACTION trial that Rachelle had mentioned earlier looks at coping and quality of life, which is impacted in the early palliative care trials, right? So you’d think we’d be able to move those outcomes a little bit more with a conversation, but they also had trouble with that.

Eric: And I think it’s hard too, because how much of it is these big researchy outcomes that we care about, versus like there are distinct populations that really benefit from things like a living will, assigning a surrogate decision-maker, that are not your traditional next of kin folks that most states have.

Eric: And we had Randy Curtis on the podcast too, which she talked about in this JAMA paper. Like some of the other outcomes that may matter too, including feeling like… Maybe it’s like decreasing burden to your family members or how should we think about, like what are the important outcomes? And how much of it is… Because we all have those N-of-1 cases where I would say vast majority of times, advance directives don’t really help me. However, I can quickly think of cases where thank God we had a surrogate decision-maker that was assigned in that DPOA paperwork or that at least there was something that gave us some path forward…unrepresented folks.

Rachelle: Yeah. Or the cases where someone actually said, “I never want a feeding tube.” Where you’re having a conversation with this family in the ICU and then they pull out the paperwork and you’re like, “Oh actually, your mom did all their work for you. You don’t have to make this decision because we have this information right here.”

Eric: Yeah.

Rachelle: So that’s like the ideal scenario, right? Where the patient does their work ahead of time, maybe writes it down or shares it with their family, ideally, and you can use it. But that’s really the ideal and not the reality that most of us kind of live in.

Eric: A lot of times it’s still locked up in someone’s safe or in a lawyer’s office.

Rachelle: Yeah. Well, the other thing I think about is this idea about utilization and hospital days. I think one place where we got into trouble was that people kind of said, “Well, advance care planning is the answer to reducing our hospitalization, reducing our utilization.” And I think that’s dangerous. And I also think, we still operate under pay for… We get paid for the services we provide, right?

Eric: Yeah.

Rachelle: So like when the surgeon can do surgery, they do surgery, and when the radiation oncology… And so I wonder, and I don’t know the answer to this, where we have these groups where we think about more population health and how can we help this person stay healthy? If the incentives are aligned better to provide care where people feel like they’re… where it’s patient-centered care, you know?

Eric: Yeah.

Rachelle: I think that would be better than necessarily looking at utilization or hospital days, et cetera.

Eric: It also feels like there’s a right tool for a right population. And for me, there’s an advance directive for particular populations. There’s these serious illness discussions. I’m wondering, since we’re bringing up outcomes and we’re talking in a podcast with Sean about the outcomes, and Rebecca, debating what the outcomes are in advance care planning. What are the outcomes though of serious illness communication?

Eric: Because a lot of the things I hear that’s bad about advance care planning, it’s complex, there’s too many steps, we don’t know how to do it well, that kind of feels like the same when we think about serious illness communication. And I just gave you an example of the VA has a Life-Sustaining Treatment Initiative, which is, I think, built around a hybrid… Like if it was in the Venn diagram of Alex, it’s somewhere in the middle. Because, to be honest…

Alex: POLST for the VA?

Eric: Yeah. Well, it’s more than a POLST. POLST doesn’t include values, goals or illness understanding. And in the VA, it starts with illness understanding, then it goes to goals and values and then it goes to like, what are their preferences?

Eric: The problem is, doctors love check boxes. So it’s usually… There’s not much written in there about goals or values and it doesn’t actually help when it’s not written in there. Because there’s not that answer to why. Why did they choose to be DNR or not have a feeding tube? Because when you’re in there with the conflict with the family members, the why is so incredibly important. So is there data around serious illness communication?

Juliet: Let me start with this one, Rachelle, and then you can add. You know, Eric, I think this is partly a question of how do you measure slow culture change, right? Because the fact that at the VA has that form, that’s an improvement, actually.

Eric: I would agree. I actually… Yeah.

Juliet: You know, Alex and I trained together. So when I was a new attending, if I had a little page that was like, “Patient was dyspnea,” it wasn’t quite running, but I would go really quickly. Because more than once, I would walk into the room and my patients would be literally gasping, like gasping. And I just learned that dyspnea was unrecognized until people were really in extremists, right? And that’s what I learned 15 years ago. But that hasn’t been true for, I would say, a decade, right? It never happens anymore. Our culture has changed. Those patients are treated earlier. Those patients are on hospice dying, they’re not in our hospital anymore.

Juliet: And so the question is like, how do we… There are these massive shifts because that’s not just about symptom management. Someone had a conversation or five with that patient to get them to hospice so that I didn’t have to see them gasping on Philips 22. And so how do we have this measure, this slow culture change that’s happening over time, right? Because you’re not going to get it in a study.

Eric: Yeah.

Juliet: But you can see it.

Eric: Yeah. It’s kind of like the feeding tubes in advanced dementia. There has been a shift and that shift in the decline of feeding tube use in advanced dementia has been documented. Rachelle, what are your thoughts?

Rachelle: So I think there’s the process outcomes, but we were able to see that. We had conversations that happened earlier. They happened more often. They had more to them. They had actually information about what the patient’s values and goals were. Essentially what you’re getting at Eric, is that why, you know?

Eric: Yeah.

Rachelle: Maybe their mother died with a feeding tube and they never wanted to have that, right?

Eric: Yeah.

Rachelle: But I think things that are really promising and I’m excited about are this question, you know, Bob Gramling’s Heard and Understood. It’s hard to argue that that’s not a patient-centered outcome and we’re doing, I think, the right work. The HPM is doing the right work and NQF to see, does this actually work? This question of Heard and Understood.

Rachelle: The other things we looked at as secondary outcomes, depression and anxiety. And I think it’s not surprising that we saw anxiety was reduced when we had serious illness conversations, because I think people are worried about it and having an outlet to discuss can be really helpful.

Rachelle: The thing that we looked at, and I think we bit off more than we could chew, was goal-concordant care. And I do not have an answer to that. I think it’s a really hot outcome. Sure, it’s the holy grail, but I’m not sure how to do it. We need someone to think about that. I’m not sure it’s the right thing to be spending a lot of time on right now.

Alex: Yeah. Scott Halpern has a nice perspective in the New England Journal about a framework for conceptualizing goal-concordant care.

Rachelle: Yeah.

Alex: Hard nut to crack.

Rachelle: Yeah.

Alex: Eric, you want to… Well, I wanted to ask one more question. Well, first, I wanted to make sure that our listeners know that we talked about serious illness communication previously in a podcast with Rachelle and Jo Paladino, who is also an author on this JAMA paper. And unfortunately, couldn’t join us today. So we’ll link to that in our show notes.

Alex: And I just wanted to ask briefly, what are the next steps for serious illness communication? Any studies planned from your perspectives, any landmark trials going on that our listeners should know about?

Rachelle: So one of my questions or things I wonder about is whether the structure actually can help quality. So if we actually follow this structure and document, actually document it, does it help quality? And one study I’m doing right now and I don’t know the answer because we’re in the middle of it, is to look at disparities in care and see if that structure might mitigate that. I don’t know the answer to that.

Rachelle: I’m interested to see Annie Walling’s work in California, is working on some things. I think the pragmatic trials are really promising as an approach to this. Juliet, do you have thoughts?

Juliet: Just that one of the challenges is, we really think this is a culture change effort and within an institution you can’t randomize, right? So you can compare institutions, but you really have to do the hard work within an institution to train the 2000 clinicians that take care of patients with serious illness and then get them to document in the right place so that it’s visible to other people.

Juliet: Our experience at Mass General was that, that’s hard to do and there’s workflow issues. We have Epic and there were insurmountable challenges or very difficult challenges with getting the kind of documentation in the workflow that, if you’re really trying to do a intervention at this level, can make it hard. And so I think it has to be well-planned, but I think it also has to be a whole institution has to change. And that takes a lot of work and a lot of IT support really.

Eric: Yeah.

Rachelle: I do feel like we’re all kind of mid-career now and I do think, if we really think back to where we were 10 or 15 years ago, we’re ahead. We’re ahead.

Eric: Yeah.

Rachelle: And I think that, I love this question that Juliet’s posing of this slow change over time. The other trial that we have, [Anna Totin] at OHSU is looking at the Serious Illness Care Program, will have some data for us in the next year or two to look at. So a Corey funded trial.

Eric: Okay. My last question is going to be the magic wand question. Juliet, if you had a magic wand, could do anything around advance care planning, serious illness communication, what would you use it on?

Juliet: I would use it on EHR.

Eric: On EHR? Tell me what would you…

Juliet: Fully Integrated electronic medical records system that made this very easy for clinicians to do. Connected with a dashboard so I would know what they were doing. And I think if you could build that and then bring it to institutions, it could be scalable. But to build that, add institution one off, it’s very difficult.

Eric: Ye of great faith in the EHR. Wow.

Rachelle: All of that structural change.

Alex: It’s true though, like as much as we are annoyed by it, we’re also, our lives are dictated by it. So you might as well include the intervention in the EHR embedded there. It’s like a stealth intervention. That’s great.

Juliet: Well, and it reinforces the training. So when we have our structure within the EHR and people document, they then are forced to remember the pieces of the communication framework. It kind of makes them better next time.

Eric: Right. Bernacki?

Rachelle: Mine is slightly different. It would be Eric whispering in everyone’s ears, “Don’t skip the steps. Don’t jump to hospice.” So ask about illness understanding, ask about, you know… Give a patient-centered prognosis, talk about values and goals and make a recommendation. You could use the Serious Illness Guide, you can use VitalTalk, but follow a structure. Follow a structure and treat it as a procedure like you would any other procedure. And don’t skip the steps.

Eric: And I love that too, because part of the recommendation could be… So we did a New England Journal family meeting video, and part of it was to show a recommendation could be that we’re going to talk another time. We don’t need an outcome other than, “Let’s meet again.” So I want to thank both of you for joining us on this podcast. Before we leave… Oh, I forget the song name. What’s the song name, Rachelle.

Rachelle: The Weary Kind.

Eric: Oh yeah, Alex.

Alex: (Singing).

Eric: Juliet, Rachelle. Very big thank you for joining on the GeriPal podcast.

Rachelle: Thanks for having us.

Eric: And big thank you, Archstone Foundation for your continued support, and to all of our listeners.