There are a lot of old myths out there about managing urinary tract symptoms and UTI’s in older adults. For example, we once thought that the lower urinary tract was sterile, but we now know it has its own microbiome, which may even provide protection against infections. So giving antibiotics for a positive urine culture or unclear symptoms may actually cause more harm than good.

On today’s podcast, we are gonna bust some of those myths. We’ve invited some very special guests to talk about the lower urinary tract – Christine Kistler and Scott Bauer.

First, we talk with Christine, a researcher and geriatrician from the University of North Carolina, who recently published a JAGS article titled Overdiagnosis of urinary tract infections by nursing home clinicians versus a clinical guideline. We discuss with her how we should work-up and manage “urinary tract infections” (I’ve added air quotes to “UTI” in honor of Tom Finucane’s JAGS article titled “Urinary Tract Infection”—Requiem for a Heavyweight in which he advocated to put air quotes around the term UTI due to the ambiguity of the diagnosis.)

Then we chat with Scott Bauer, internist and researcher at UCSF, about how to assess and manage lower urinary tract symptoms in men. We also discuss Scott’s recently published paper in JAGS that showed that older men with lower urinary tract symptoms have increased risk of developing mobility and activities of daily living (ADL) limitations, perhaps due to greater frailty phenotype.

Eric: Welcome to the GeriPal podcast. This is Eric Widera.

Alex: This is Alex Smith.

Eric: And Alex, who do we have on the podcast with us today?

Alex: Today we are delighted to welcome Chrissy Kistler, who is a geriatrician researcher in the Department of Family Medicine and Vision of Geriatrics at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. Welcome to the GeriPal podcast, Chrissy.

Chrissy: Thank you so much for having me. I am so excited to be here.

Alex: And we’re delighted to welcome Scott Bauer, who is an internist and geriatric urology researcher in the Departments of Medicine and Urology at UCSF. Welcome to the GeriPal podcast, Scott.

Scott: Thanks, Alex. Super excited to be here.

Eric: We’re going to be talking about all things lower urinary tract infections, lower urinary tract symptoms. But before we get into this topic, does someone have a song request?

Chrissy: I do. Can I tell you about why I chose it?

Eric: Yes.

Chrissy: This is in homage to my children who I sing this to them on a not infrequent basis, and also the lower urinary tract. And we would like to request, Let It Go.

Alex: Oh, very appropriate. All right, here we go.

Alex: (Singing).

Chrissy: Yap. Good. Thank you.

Alex: That was fun.

Scott: Amazing.

Eric: I want to know from both of you, urinary tract symptoms. How did you decide this is going to be my focus of research and yeah? Scott, I’m going to turn to you first.

Scott: Sure. Thanks Eric. I get the question a lot. And so I trained as an epidemiologist before medical school, and started out studying prostate cancer. And something that I learned and then started to study afterwards was that men with prostate cancer use the future effects of treatments on urinary and sexual function to drive a lot of their treatment choices. And so that was one, very interesting to me. And two, I then went on to study lifestyle risk factors that affected those outcomes. And in my medical training, becoming a primary care doctor, I realized that older adults, women and men were having a lot of these same symptoms. And unfortunately, a lot of our treatments have modest efficacy. So that really motivated me to start studying them in older adults, which is what I do now.

Chrissy: That’s fascinating. So I actually got started in cancer screening also, thanks to some mutual colleagues. Very interested in decision making around as we get older, individualizing care, sort of patient centered, values driven, it’s a tough decision to figure out. Like for me, my NF1, is it a good idea to get screened for cancer or not? And so really am fascinated by tough medical decisions. And interestingly, infection control in older adults is also a really challenging medical decision. So it’s a really hard nut to crack in terms of what is a UTI? What isn’t a UTI? What do I prescribe? How do I do deal with it? What do I work up and has profound harms to people in terms of if we don’t get it right? That is we miss a UTI, they could get urosepsis, they die. On the other hand, we give them tons of antibiotics, they get C. Diff. They get massive resistance, they die. So it’s kind of this really challenging decision and that’s why I’m interested in it. But very few people also aren’t necessarily as fascinated by this.

Eric: I am super interested in this topic and just so many questions I have to ask. I’m going to start with some basics. So Scott, a lot of your stuff is on lower urinary tract symptoms. What does that encompass? What is that exactly?

Scott: Yeah, so it is an umbrella of symptoms that occur anywhere from the start of making urine all the way to the point of finishing urinating in the toilet. So, it can be symptoms that occur while you’re starting to store urine in your bladder, but you’re having sensations of urgency or spasm. You are not storing urine successfully. You’re having leakage of urine. And then when you start to void, you’re having any number of difficulties with that process. You’re having trouble initiating urination. The flow is extremely slow or starts and stops. Once you think you’re done urinating, your bladder still feels like it’s full, or you feel like you have to go again within unreasonably short period of time. That entire spectrum is called the lower urinary tract symptoms, and affects older women and men at increasingly high rates as they get older.

Eric: And how common is it in the elderly population?

Scott: Yeah. So older adults between a third and a half have some clinically significant degree of lower urinary tract symptoms, depending on how you define it. So very common.

Eric: Its high. And do we know is it associated with any outcomes, like bad outcomes, or is it just a nuisance?

Scott: The listeners are probably well aware that urinary incontinence is one of the kind of classic geriatric syndrome. So once that receive that label there was a lot more studying of bad outcomes that occur after someone develops urinary incontinence. But what a lot of my work has been doing is trying to shine a light on all of the other lower urinary tract symptoms to increase awareness that older adults with those symptoms are also at higher risk of mortality. As well as what we’ll kind of get into in the paper that we’re discussing today, ADL limitations and mobility limitations.

Alex: Can I ask what’s the Venn diagram between urinary incontinence and lower urinary tract symptoms?

Scott: Yeah, that’s a good question. In women, it is very overlapped. There is a small… It’s much less common for an older woman to have bothersome lower urinary tract symptoms, to not have some degree of incontinence, whether it’s stress or urgency or mixed a little bit of both. In men, there is a lot less overlap and for a lot of my… So I don’t have a number for you, but I can tell you that those circles start to separate in men. But both are prognostically of similar importance.

Eric: And then as we talk about Venn diagrams, probably the most common reflexive thing that providers do when they hear about lower urinary tract symptoms is they check a UA. They may send a culture. How do urinary tract infections fit into this picture, Chrissy?

Chrissy: Yeah. So that’s the problem, right? So we have this kind of ocular ordering reflex, we see a worrisome nitrite and leukocyte esterase and we order the culture like that. Like you don’t even think about it. And the problem with that is that we will find asymptomatic bacteriuria. Bladders of older women, particularly older women, less so for older men are likely colonized. And the older we get, the more likely they are to be colonized. And so this is not talking about our healthy 30 year old ladies’ bladder, not talking about a pregnant bladder either. We’re talking about an older woman’s bladder. We know that there is bacteriuria in there. And we know that if we treat that bacteriuria without the presence of infection, we will cause more resistant bacteriuria in the future. So that when they get an actual infection, we’ll be left with significant drug resistance and likely a nastier infection. And we do not improve outcomes. We do not improve mortality.

Eric: Well, can I ask that… I’m struggling with the idea like what exactly is a urinary tract infection? I remember Tom Finucane had a great article about using air quotes around urinary tract infections, because like a, the bladder is not sterile. So if there is a microbiome of the urine, like we just don’t run sensitive enough tests in most people, and maybe an imbalance of that microbiome that causes symptoms. And I think about it like the skin. Like I can culture my skin and I can pull up some bacteria, but that doesn’t necessarily mean that I have a skin infection. So how should I [inaudible 00:10:45] that with the bladder. Like if I-

Chrissy: You know you have a skin infection when it’s like red, and pussy and it’s like spreading up your arm, so that’s what we can look at the bladder. Like if I don’t typically have dysuria and I start to have dysuria. If I don’t typically have urgency or frequency and I start to have those things, that’s a clue that you might want to suspect a UTI. It still isn’t 100% slam dunk. I’ve seen lots of ladies with chronic incontinence issues who get a dermatitis, the chemical dermatitis. And now they get pain with urination, but I look down there and I’m like that does need some TLC, and we’ve got to put some cream down there and life will be better. We don’t have to give you an antibiotic. Or they get fecal impaction and they’re constipated. And now they’re having incontinence because their bladder can’t do what it’s supposed to do because they’re constipated.

Chrissy: So we have to make sure we’re not having a premature, like oh my gosh, again that sort of reflexive must be a UTI. But really those urinary tract signs and symptoms should be driving your diagnosis. That is really what you need to be looking at. If it’s new onset, dysuria, urgency, frequency incontinence, for men urethral purulence, but there’s still debate there. If you look among the greats in the field, like Stone and Lob, and all of these they don’t 100% agree. Then there is not perfect overlap. So it’s not-

Eric: So you just mentioned a bunch of guidelines, is that right?

Chrissy: That’s right.

Eric: All right. So, I’m just also thinking about outcomes. You mentioned earlier… We talked about outcomes of lower urinary tract symptoms, outcomes of urinary tract infections. I think Tom Finucane also argues that for a long time we didn’t use antibiotics for urinary tract infections, like people get over it. And it’s not necessarily just because we start somebody an antibiotic and they get better, it’s that the antibiotic helped. Is it the same thing with lower urinary tract symptoms? So we have a good idea with I guess infections. What actually helps with them is, does everybody need an antibiotic?

Chrissy: Yeah, that’s a great question. The answer is if you’re basing it off the culture, so the culture grew back bacteria then probably not, because those are probably not real infections. I think our big issue here is we’ve got this kind of gobbledygook of people who probably have serious lower urinary tract disease. We have people who are going to be at risk for getting upper urinary tract issues and getting septic, because that’s what’s on the line. Sepsis is the boogieman in the room. Nobody wants anybody to get septic and die from urosepsis, right? But then there’s probably a good 50, 70% of the population who gets labeled as having again air quote UTIs they don’t. And all what they have is like maybe they’re a little dehydrated, so their urine smells kind of funny. Maybe they are having pain and so they’re not making it to the bathroom in time. There are lots of other things that might be going on that we’re going to ignore if we label everybody, oh, this is just a UTI.

Alex: Can I just reiterate what you said because that’s remarkable. 50 to 70% of people who are diagnosed with UTIs probably don’t have a UTI. Is that right?

Chrissy: And that’s in the nursing home population, and particularly, it might be lower like 30% in your outpatient clinics, but it is a huge chunk.

Eric: All right. Chrissy, I’m going to pose a couple questions to you then. We got a call tonight, I’m on call, nurse says one of my nursing home hospice patients started to have some foul smelling urine.

Chrissy: Hospice?

Eric: Yeah. But they still have months to live. So antibiotics still aligned. And like it’s a UTI, that’s not comfortable.

Chrissy: Sure. You want to know what I would do?

Eric: Yeah. Just foul smelling urine.

Chrissy: Foul smelling urine. Foul smelling urine is not a sign or symptom of a UTI. They need to increase their hydration. Are they not eating and drinking well enough?

Eric: Yeah. Maybe it’s the asparagus that they ate for dinner.

Chrissy: Well, and you can monitor. So we don’t abandon people. We don’t say like, “Okay, no antibiotics means no nothing.” What we should say, “This is what you do.” What we should say to our nurses is, “Thank you for letting me know. I appreciate that information. I want you to monitor their blood pressure and their vitals, Q shift…” Which maybe we don’t normally do for our hospice patients. “And I want you to push fluids on me. And if they spike a fever or they start having any other stuff, I want you to let me know. And we can do something about it at that point.”

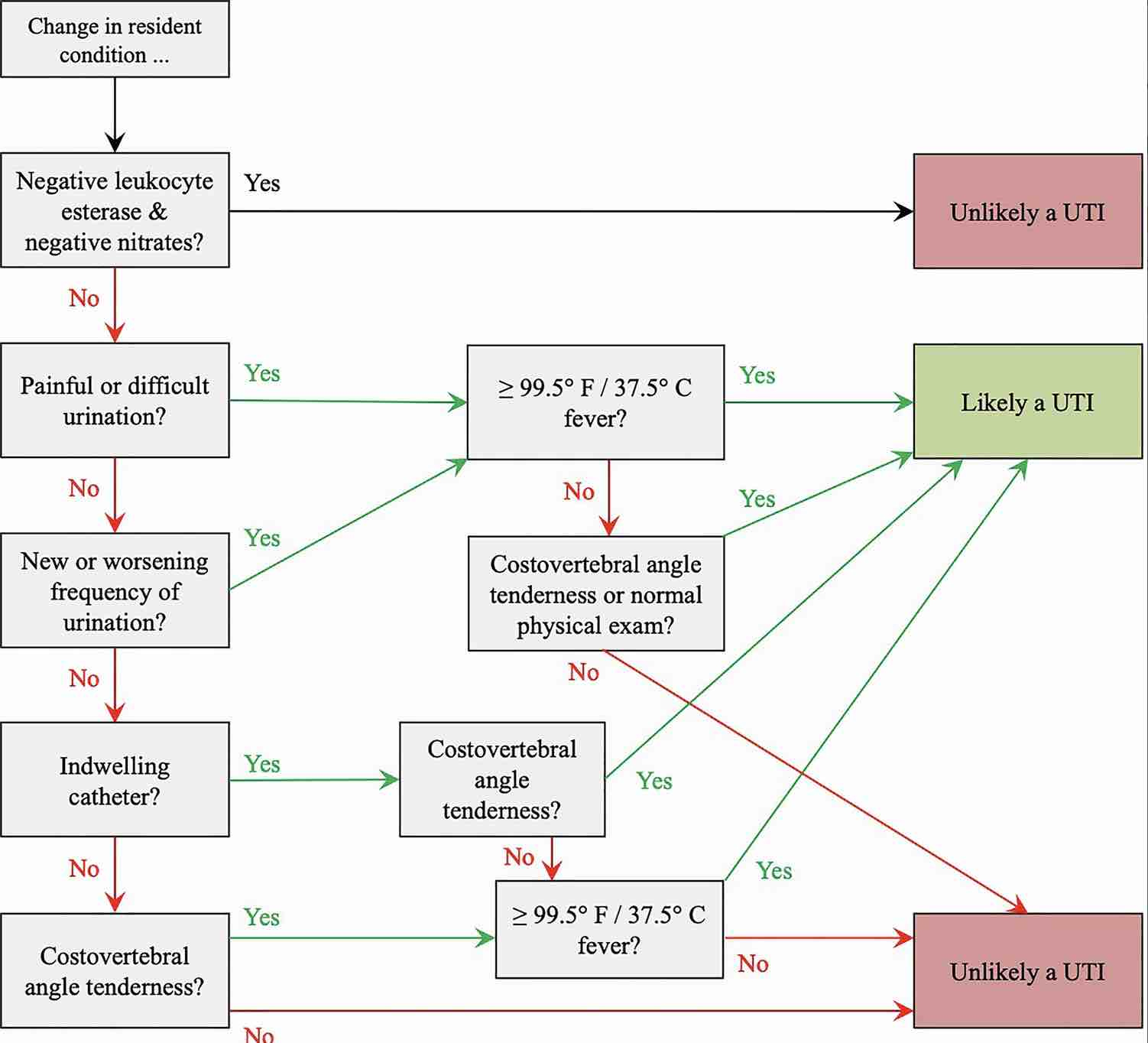

Eric: And I really liked your article in JAGs because it had a nice flow diagram, and like an algorithmic approach. And I’m just going to describe it. It starts off with the change in a resonant condition. Can you tell me what that meant?

Chrissy: That means it’s what our nurses come to us with. It’s like she’s acting different. And then they tell you what the difference is.

Eric: Great. So that could be symptoms in a patient with dementia, maybe some delirium and off. And then the next one is-

Chrissy: Mental status changes, there is decrease in their PO intake, their urine smells funny, all those kinds of things.

Eric: So the next thing you have is negative leukocyte esterase and negative nitrites. Are they negative or are they positive? Is that kind of where we should go next or should we tease up the symptoms a little bit more?

Chrissy: Right. So the issue is that why… It’s kind of like a D- Dimer, right?

Eric: Yeah.

Chrissy: Negative nitrite, negative leuks is so rarely going to be a bacterial infection in your bladder. That it’s a good thing to say, “Oh, okay. Whatever lower urinary tract signs and symptoms you’re about to tell me, maybe it’s not that.” The problem is that if you get caught in the trap of it’s a positive LE and positive nitrite, now you got a rabbit hole you’re going down.

Eric: Yeah. So I’ve always heard that it’s a good indicator whether or not the culture is going to be positive, but that’s it.

Chrissy: Yes. Great. That’s exactly right.

Eric: Okay. And then you go to symptoms. Do they have painful, difficult urination, new worsening frequency of urination? And that also kind of leads you down the path. So we’re starting to think, it’s not just the culture, or it’s not just the Leukocyte esterase and negative nitrites in the UA. It’s also okay, let’s dive into the symptoms. So what symptoms would… I guess you said there’s some also not agreement on what counts as a symptom, right?

Chrissy: So there’s been a lovely effort I think in the past five to 10 years to kind of get some expert consensus, because that is as good of a level of evidence as we have. So my algorithm in that article is really based off the work Van Bo et all have done. To take experts in the field like those names I said before, pull them all together and see if we can get through a deified process to some agreement, because that’s frankly as good of a gold standard as we have.

Eric: So some localizing symptoms, where does delirium fit into those non localizing?

Chrissy: Right. So obviously if you have systemic signs or symptoms, that’s important to know. So if they’re tachycardic and hypotensive, if they’re having really frank delirium, the problem is a lot of our patients particularly in the nursing home have some degree of cognitive impairment. And they have good days and bad days. If the neighbor down the hall isn’t sleeping well and is making a ruckus, then my dementia… I’m not going to sleep so well, so now my behavior might be a little off. And so trying to tease out the mental status changes piece I think is hard. But if they have some of those true delirium that we think could be a definite change in their mental status, we know delirium as a cardiac equivalent. It’s like having a heart attack. It needs to be worked up and deserves to be looked at. I think a lot of times though, it’s this like, well, she’s just a little off today.

Eric: Yeah. And should we think anything different about people with indwelling catheters?

Chrissy: Oh, 100%. Yeah, absolutely. Those people really for them because they’re not going to have as many lower urinary tract signs and symptoms, they may say, “Gosh, it hurts more here.” They may have more CVA tenderness, really for those people… God forbid they have a fever, if they start having rigors stuff like that, you just need to pull the trigger and start something.

Alex: If I was on call for a nursing home and I wanted to ask the nurse to check for costovertebral angle tenderness, how would I walk the nurse through that?

Chrissy: Yeah. So I think you could say, when you go and examine them if you could, one you want to check for super pubic tenderness. So push right above the pubic bone right down low where the bladder is. And then I want you to feel in their back, kind of in their lower back on the sides of their lower back, and just kind of tap it for me and see if they have pain down there. That’s how I would do it. There’s not been a study of looking at how best to ask that, but that’s how I do it.

Eric: So this is a complicated pathway, right? So you’re trying to integrate the patient’s past history, like do they have these symptoms all the time? You’re trying to include information from symptoms in a population, also in a geriatric population that may have multiple reasons going on. Then you’re trying to include some lab data, including a UA to help inform whether or not it’s likely or not likely a UTI. How good are clinicians and nurses in following these guidelines or diagnosing a UTI? I hear it’s over diagnosed.

Chrissy: Right. So when we took for our study not to get too like technical, but we wanted to see in some hypothetical situations. These aren’t real life patients, these are hypothetical patients we put together and we said, “Given this hypothetical patient that has all those things you just talked about. Lots of information in there. Do you think they have a UTI or not?” And what we found is when we compared it to the guideline, they were pretty good at saying… The guideline said it was a UTI that they had a UTI. They were less good at saying when the guideline said, “No, it’s not a UTI.” Saying, “No, it’s not a UTI.” And in fact, in a lot of cases they said, “Oh no, that’s still a UTI.” So there was that over diagnosis that’s happened.

Eric: Do you remember any of the examples? See if I can get on any of them right.

Alex: Challenge us, challenge our listeners.

Chrissy: Well, right. So we took every single one of those and we made thousands of scenarios that we put people through. So it’s hard. I can make one up for you.

Alex: Yeah, make up a hard one for us.

Chrissy: Okay. I’m going to pull up the example we used in a study we did. Imagine you receive a telephone call from the nursing home about the following resident. The resident is an 80 year old man who has been in the nursing home for the past year. They have no history of UTIs or current and dwelling catheters. They’ve had reduced intake of food and liquids. They are sleeping more than usual. They have new or worsening odor. They have a body temperature of 97.5. They have new redness on their leg. They have a positive leukocyte esterase positive nitrites, urine culture is pending. The family asks you for an antibiotic and their goals are limited additional interventions. Would you prescribe an antibiotic? Would you say that they have a UTI?

Eric: So I’m going to ignore the smell of the urine, because that could just be some dehydration. The only localizing symptom that we have I believe, if I remember correctly is potentially something going on in their leg. So I have a diagnosis that is potentially more likely what’s causing this person. So I’m not even going to use air quotes around urinary tract infection.

Chrissy: Great. And what’ll happen is people will say, “Oh, they’ve got to change in odor. And I’m going to prescribe it.”

Alex: So when you were saying something going on with their leg, are you talking about the redness?

Chrissy: Yeah. The redness and on their physical exam they’ve got new redness on their leg.

Alex: Right. So in this case you would clean the area and treat with some cream?

Eric: Or figure out what’s going on in the leg.

Alex: Yeah. Right.

Chrissy: Exactly. Is it they’re having worsening heart failure and they’ve got some lower extremity edema. Are they developing chronic diastasis? Do they have a fungal infection? Again, you’re going to go down that rabbit hole of skin and soft tissue. You’re going to get away from the bladder.

Eric: So, I think important take homes is really we want localized symptoms, not reflexively just ordering a UA and culture. And recognizing the UA mainly tells us if the culture is going to be positive. And just because they have a culture positive doesn’t mean they have a urinary tract infection. I think I’ve been hearing this for a while and it sounds like it’s still an issue in nursing homes. Is there anything we can do to improve this?

Chrissy: That is a great question. I feel the same way. I think that there’s probably a lot we can do. I want to involve our pharmacists more in this process. I think that they can help not just in the right direction is part of my hope. There are some ongoing trials to look at that. I think that using the culture results as a flag, to stop. If it comes back-

Eric: The problem is culture results don’t come back until like day number three, right?

Chrissy: That’s right. And what we find is people don’t stop the antibiotics they start. We’ve got to learn how to stop some of the things that happen.

Eric: Yeah.

Chrissy: So I think people need to get much more comfortable with reevaluating, with that watchful waiting piece we do. Push in fluids, checking vitals, let’s see if we can clear up whatever this is. Let’s give it a little tincture of time, if we see any sign of a fever, okay we’ll prescribe. So holding back on prescribing. Also, we tend to prescribe like fluoroquinolones… I know we don’t in this room prescribe fluoroquinolones, but there is a lot of fluoroquinolone prescribing. Everybody goes to Levaquin and that’s bad. It’s bad for our patients. It’s bad for resistance. It’s bad for C. Diff and we need to stop.

Chrissy: So when people come into your nursing home, maybe you… This is something we’ve been thinking about doing in ours, is you say, we are an antibiotic steward nursing home. This is what that means. You may find it’s different because there’s this whole culture that these people have aged into for decades of every time she gets a little off her food, we’re going to give her an antibiotic. Well, can we say, you’re coming in here, this is a bit of a culture shift. Can we help families as well as our nurses and everybody get there?

Chrissy: It’s going to be a multilevel intervention. It’s going to take efforts at the point of care with prescribing. It’s going to take efforts on the family side. It’s going to take efforts with system management, and getting the labs making sure people are going to stop antibiotics that don’t need to be potentially started in the first place. That whole process has to be better tuned.

Eric: Yeah. I want to move to you, Scott. Hey, do you have any thoughts on the conversation so far before we dive into kind of some of your research?

Scott: I do. Well, one, I thought about this before today, but even hearing Chrissy talk about it more. The challenges of treating lower urinary tract symptoms in older men have a lot of overlap with treating symptoms of urinary tract infections in older adults in nursing homes. And yet our diagnostic tools are even more limited. I would say the harms are probably less, so maybe that’s okay. But the tendency to assume what seems obvious and just go down that road and ignore everything else, I think is very strong and in a very similar way to treating positive UAs or kind of non specific symptoms of possible urinary tract infection. So, yeah. That’s kind of what I was thinking about when Chrissy said it.

Eric: So again I’m going to do a hypothetical, an 80 year old veteran comes to your clinic, new onset of some lower urinary tract symptoms. Do you have like a script that goes through your head to kind of how to ask kind of more about that in a way that people are actually going to give you real answers? And this is a hard subject to talk about. And then how you think about the workup?

Scott: Sure. So taking a step back and thinking really big picture, the first I think is the fact that 80% of 80 year old men who die and get an autopsy have BPH, has really driven the fact that when an older man comes in with urinary symptoms and there’s no really other obvious causes… We’ll get into kind of what I rule out. It is so easy to just assume it is an enlarged prostate that needs to be shrunk or relaxed or targeted in some way to relieve the symptoms. And I think that assumption is what a lot of my work is trying to kind of undo and bring in all those awesome, that toolkit of an internist. So to think more broadly and to avoid treatments that are not beneficial and potentially causing harm.

Eric: You’re not just going to start everybody on Finasteride and Tamsulosin right away.

Scott: Exactly. Yeah. So, that’s kind of my-

Eric: That’s like the Chrissy’s antibiotic.

Alex: Fluoroquinolone equivalent. Yeah.

Scott: Exactly. Don’t just reach for that prostate specific medicine. So what I do do though is I ask things like we do with any new symptom. When did it start? How long has it been going on? How has it been changing over time? What was going on at the same time that the symptoms started? What are other associated symptoms? Comprehensive review symptoms of systems. Are there signs and symptoms of urinary tract infection and are there other red flags that require a more rapid workup and treatment? Is their hematuria, gross hematuria or a history of microscopic hematuria? I do a chart review. Or a history of kidney stones. Have they ever had acute urinary tension?

Scott: And when they describe symptom are they having symptoms of acute urinary retention right now but they’re focusing on a subset of the symptoms? I also review all of the urinary symptoms from dysuria. So storage symptoms from like episodes of urgency and frequency during the day and night time and is it one more than the other? Are they having urinary incontinence? Going back to for a long time urinary incontinence was not asked about nearly enough in older adults, women or men. Patients, sometimes that’s the last symptom that they bring up. They might bring up another urinary symptom instead. If you don’t ask, you don’t know. And then all the way to-

Chrissy: That’s a great point. I love that point. You don’t ask, you don’t know.

Alex: Yeah. That’s key.

Eric: And that’s one of those symptoms too that can affect a lot of them. Like you hear about folks who no longer go out or go to the movies because they’re worried about that, but they may not bring it up in clinic.

Scott: Totally. And to kind of expand on that, not only… There’s a bunch of other symptoms that I also ask about. But I also ask, how is it affecting your life? What is it preventing you from doing right now and how is it preventing you from doing it right now? Is it that you feel like there’s something wrong, and so you feel sicker, and less healthy and so you’re not doing things? Is it practically speaking preventing you from going out and exercising, or going to the movies, or spending time with family because you’re worried about being away from the bathroom? Or are there certain things you’re doing that make it worse? And thinking about triggers. So, that’s a kind of scatter shot where I start.

Eric: Do you use something like the AUA score for like symptom severity and?

Scott: Yeah. So there are couple of a few things-

Eric: Not Scott the researcher, but Scott the primary care provider who has to see another patient in 15 minutes.

Scott: If I have refilled it in the room that I am, printed out and it’s right there for me and it’s not going to take a bunch of extra time. Or I can really quickly ask somebody that I work with to help me out, and print it out for me and bring it. Or I have patients fill it out while if I have to step out of the room. I do think that it is extremely helpful to know, one, how the symptoms that they’re describing to you map onto clinical lead defined categories of severity. It also is extremely helpful for tracking changes over time. And there’s a built in question about how bothered they are. So if you forget or it’s not a part of your practice to ask that, it really gives you a good reminder to think more holistically and also think about how practically it’s affecting the patient.

Eric: So you ask all these questions, you get a good history and then you prescribe Finasteride and Tamsulosin?

Scott: Oh, we skipped so many steps. So I am really big on… A thing that I have become very passionate about is lower urinary tract symptoms being the initial symptom of another condition. So UTIs is one, and that’s why we get UA in all men who are coming in with new lower urinary tract symptoms. But heart failure and polyuria from poorly controlled diabetes, any sort of volume overload state when someone is collecting fluid in their legs, it stays there all day. They don’t have any urinary symptoms during the day. They lay flat to go to bed. That fluid does go back into the circulation. And so suddenly there is more fluid available to be filtered, and to go into the bladder and make you wake up in the middle of the night.

Eric: Nocturia, thinking about that as a repositioning fluid shift.

Scott: Exactly. So I really like to take a step back and make sure have we thought about all the other conditions that are secondary causes of lower urinary tract symptoms? And then I think it would take too long, but there are a lot of different approaches to prescribing BPH medications. And I’m someone who likes to try, see how the symptoms change. Then see if stopping the medication makes the symptoms come back. There’s huge placebo effects that are really hard to detect and know what to do with. But starting and stopping medicines is a really good way of identifying those.

Alex: Like an NF1 trial. Yeah, Chrissy.

Chrissy: There is also regression to the mean, right?

Scott: Exactly.

Alex: What is that?

Chrissy: That’s where people report things at their worst, but it naturally fluctuates over time. And so it would get better whether or not you treated it. I think there’s a dope phrase and epic that you can use. And we have one that we stole from like our urologist for the AUA. So I don’t know if there’s other people who might have similar things out there.

Eric: And real quick too, because I want to get to your JAG study. Are you doing like bladder scans and more testing outside of some like basic labs?

Scott: Yeah. So our VA clinic doesn’t have Uroflowmetry available on site. Our urologists have said, send anyone we’ll happily do that whether or not they’re a part of our clinic. We do have post void residuals and I use those frequently. And I’m pretty surprised to know kind of nationally how little that they are used to work up older men with urinary tract symptoms. The main reason being that, one, to see if they have severe urinary retention or overflow incontinence. Also, if someone has nocturia it’s because… And you think that relieving a bladder, a prosthetic obstruction will help their nocturia, you’re saying that because you think that the bladder is not completely emptying. And they’re going to bed with a partially full bladder. That is a very easily testable hypothesis with the PBR which is readily available in clinics. So I definitely don’t prescribe any BPH medications to older men who are primarily concerned about their nocturia, if they don’t have some evidence of retention

Alex: Before we get to your paper, can I ask what are the most common medications that are associated with lower urinary tract infection or symptoms in men? Causative medications.

Eric: See, Alex just wanted to start an antibiotic right there. He’s, oh, that’s an infection.

Scott: Yeah. So there are a lot of medications with kind of a slightly increased risk. The biggest one is the kind of obvious one. What time is someone taking their diuretic? And so timing of diuretics is by far the one that I deal with the most. I try to split doses so that they’re not spreading out some of the diuresis throughout the day. And when is the symptom bothering them the most? Let’s not have them take the diuretic right before that. Whether it’s at night or whether it’s in the morning before they go do their daily activities, let’s try to time it a little bit better.

Alex: I would guess in hospice and palliative medicine that opioids are a fairly frequent cause of some of these symptoms. I’ve certainly seen that clinically.

Scott: Yeah. Again, retention type symptoms I think is a common wrestle with the kind of storage symptoms.

Alex: Yeah.

Eric: All right. I want to get your JAGs paper because I think it’s really interesting. So you have these symptoms, you may start treatment after a good evaluation. What does it mean for the person who’s having these symptoms kind of moving forward?

Scott: Yeah. So what it means for them in terms of their lower tract symptoms and we’ll kind of put that off to the side. But again, a part of this kind of whole thinking about lower urinary tract symptoms more holistically, and what it means for the patients moving forward. What I observed clinically is that older men with lower urinary tract symptoms tended to have a lot of comorbidities, tended to look or appear or meet the frailty phenotype. And they also tended to do worse than my patients who didn’t have urinary tract symptoms. And so as a good epidemiologist, I kind of looked for big data sets that might be able to answer that question for me. And so in the MrOS cohort or study of osteoporotic fractures in men. I started with a group of almost 3000 older men who had no difficulties with ambulation, no difficulties with managing their money or medications independently, and no difficulties with transfers or bathing or showering.

Scott: I used the American neurologic symptom index at that visit that they did not report any of these difficulties. And I looked at the next time they were asked about mobility and ADL limitations, which was two years later. And I described what I saw and tried to adjust for all the other reasons somebody might have developed mobility and ADL limitations during a two year period. And what I found was that just like what we were observing clinically is that older men with more severe symptoms, and likely less severe symptoms than one might imagine it, they weren’t all in the category of severe which is an AUA score of 20 or greater. But you started to see increased risk as low as 13 or even eight.

Scott: That they had a twofold increased risk of developing new difficulties walking two to three blocks on flat ground, or going up 10 stairs without help and without rest. And also men in the most severe group had about a 60% increased risk of difficulty with transfers or bathing and showering. We didn’t see a lot of men developing difficulty with cognitive dependent tasks like managing medications and money. So we were pretty limited in looking at that outcome.

Eric: And the chicken and egg here is, so did the ADL and mobility issues cause the lower urinary tract symptoms, or did the lower tract symptoms cause the mobility and ADL issues? Sounds like everybody didn’t have mobility and ADL issues from the start. Will that help us with the chicken and egg?

Chrissy: Well, there’s one more option which is something else caused both of them.

Scott: Yeah. So to Eric’s point, the best way to prevent there being reverse causation is to start with a nice group of people who don’t have your outcome at baseline, which is why cross sectional studies are so limited with studying these kinds of questions. So we did our best there. They could have had mobility limitations before and they just happened to say at that visit that they no longer had them. So you can’t prove that, but I would say we did a decent job of making sure that wasn’t the case. And then absolutely, Chrissy, we are limited to what they reported they developed during that two year period. So we adjusted for new development of any sort of comorbidities that are known to cause lower urinary tract symptoms, new diabetes, new heart failure, diuretic medication use and a whole bunch of other things. So those are definitely things that we had to keep in mind and we did our best to account for, but there are always limitations to our ability.

Eric: Did that information change your practice at all?

Scott: Yeah. I think it gave me confidence to do what I was already starting to do, which is to stop thinking about urinary tract symptoms as a prostate specific problem. And to think, this is an older man who’s at risk of developing outcomes that are really important to avoid in older men. And I need to double down on making sure that this isn’t an early sign of one of those conditions. And I need to think very carefully about is the medication I’m giving them, is it going to be helpful for their symptom and is it going to… They’re already even independent of the medication I’m giving them at higher risk of having new mobility problems and ADL limitations. Is the medication I’m giving them going to help prevent that or make it worse? And several of the BPH medications are very strongly associated with falls and orthostatic hypertension. So-

Eric: The alpha blockers

Scott: Yeah, alpha blockers. And Finasteride, there’s increasing concern about incident depression and men who start Finasteride at the doses we use for BPH. So again, not only is it maybe not going to help, but it’s in some men going to hurt. We should just move a little more slowly, be a little bit more thoughtfully and really consider de-prescribing after period of time to see if the symptoms really were better because of the medicine, or maybe they were better because of regression to the mean like Chrissy mentioned.

Chrissy: I love this study. I thought it was really an important reminder that people are people. That all these systems are connected and that we really maybe let severity really should help be a flag for us. That there might be something going on here and we don’t want to just again, get those blinders on. So I thought it’s great work.

Scott: Thanks. And maybe one day we will get to the point of how providers are thinking about their prescribing habits around treating lower urinary tract symptoms, which is where Chrissy’s work is further down the road. But I think a natural direction of these kinds of studies.

Alex: Downstream, so to speak. [laughter]

Scott: That’s the first time I’ve ever heard that. [laughter]

Eric: I like it. Well, I want to thank both of you for joining us. But before we end, I think Alex is gearing up for a little bit more, Let It Go, Let It Go.

Chrissy: Everyone should join in on the chorus. We should all join in.

Alex: (Singing).

Chrissy: Yay.

Eric: Scott, Chrissy, huge thank you for joining us. That was a great conversation. Learned a lot and really we’ll have links to the JAGs papers and some of the other stuff we talked about on our show notes. So, a very big thank you for joining us today.

Chrissy: Thank you guys for having us, it’s been a pleasure.

Eric: As always thank you, Archstone Foundation for your continued support. And to all of our listeners, thank you very much.