Age is one of the great modern adventures, a technological marvel—we’re given several more youthfulish decades if we take care of ourselves. Almost nobody, at least openly, sees this for its ultimate, dismaying, unintended consequence: By promoting longevity and technologically inhibiting death, we have created a new biological status held by an ever-growing part of the nation, a no-exit state that persists longer and longer, one that is nearly as remote from life as death, but which, unlike death, requires vast service, indentured servitude really, and resources…

Part of the advance in life expectancy is that we have technologically inhibited the ultimate event. We have fought natural causes to almost a draw. If you eliminate smokers, drinkers, other substance abusers, the obese, and the fatally ill, you are left with a rapidly growing demographic segment peculiarly resistant to death’s appointment—though far, far, far from healthy.

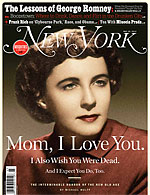

These are the words of Michael Wolff written in acover story published in this week’s New York Magazine. Even though there are some things I take issue with in this piece, the depth and honesty in his story moved me to want to write about it here.

These are the words of Michael Wolff written in acover story published in this week’s New York Magazine. Even though there are some things I take issue with in this piece, the depth and honesty in his story moved me to want to write about it here.

Wolff’s story revolves around his mothers diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease and the years of cognitive and functional decline caused by this slowly progressive neurodegenerative disorder. The course of her disease was marked by hospitalizations, major heart surgery for aortic stenosis, and what Wolff describes as a “series of stops, of way stations, of signposts” in which she goes from being at home, to needing assisted living, to needing nursing home care, to being at home with hospice.

What was most moving about this story was how he captures the heartache of a son seeing the slow destruction of the person he knew as his mother, and the frustrations of knowing that he is in part responsible for her current life:

And yet, I will tell you, what I feel most intensely when I sit by my mother’s bed is a crushing sense of guilt for keeping her alive. Who can accept such suffering—who can so conscientiously facilitate it?

The one aspect that I take some objection to is the one-sided and very negative view of disability in late life. He equates the “drawn-out, stoic, and heroic long good-bye” to “human carnage”, and backs this up with studies showing that 70% of those older than 80 have a chronic disability with over half having at least one severe disability. However, at least one study by GeriPal’s Alex Smith shows that it is possible to be significantly disabled and dependent on others for help with even basic activities of daily living, and yet also have a good self-rated quality of life.

With that said, I still think this is truly a remarkable read. As one columnist said: “force yourself to get through “A Life Worth Ending”… not because it’s a bad piece. It’s beautifully written and evocative — it’s just that it’s almost too evocative for anyone who has ever watched a loved one die slowly from illness.”

by: Eric Widera (@ewidera)