|

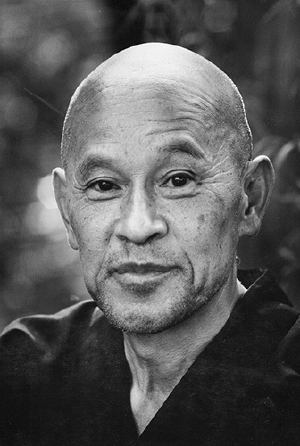

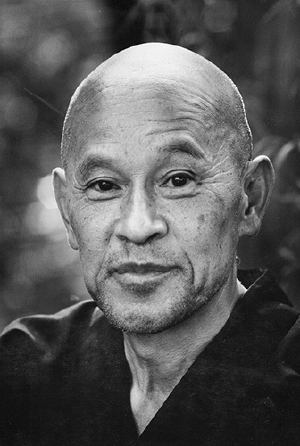

| Shunryu Suzuki by Robert Boni |

“Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind” is a collection of talks by the late Zen MasterShunryu Suzuki. The book opens with the words:

“In the beginner’s mind there are many possibilities, but in the expert’s there

are few.”

One of the reasons it is fun to attend in July is that the hospital is filled with beginners – medical students starting the wards, interns begining as doctors, and fellows learning their specialty. July is a time to see the practice of palliative care with fresh eyes and beginners’ minds. New palliative care fellows are experiencing what is routine to experts for the first time: a first call for a consult, a first family meeting, a first death.

In this spirit, I generally go back in July and write about a very basic topic that, though covered before, is well worth covering again with the fresh perspective of a beginner. Previous posts have covered the topics: how do you explain hospice? and how do you explain palliative care?

This post will cover how you talk about imminent death with family members. This situation came up today for a dying elderly veteran. The new palliative fellow asked me to summarize my approach to discussing imminent death. I realized I’d never thought about a formal approach, but her beginner’s mind was right – there should be one. We discussed it together, and we came up with the following questions that clinicians can routinely offer to discuss with family members of patients who are imminently dying.

- How much time does he have? I will offer to discuss this topic, because in my experience families want to know, but are reluctant to bring it up. I’ll say, “Do you have questions about how much time he has left?” They’ll usually nod.

- What physical changes can we expect? In particular, I like to warn families about changes in breathing patterns (Cheyne-Stokes respirations). I say, “This doesn’t happen for all patients, but as some people’s bodies begin to shut down, they will begin to breathe very slowly, then stop. And sometimes they may start to breathe again, then breathe very quickly, then slow and stop. And repeat. I just want to tell you to prepare you in case that happens.” Families sometimes are alarmed when their loved one seems to die, only to start breathing again. For whatever reason, this has been a bigger issue for families I have cared for than the so called “death rattle”.

- Can he still hear me? I like to tell the following metaphor, taught to me by Dr. Janet Abrahm. “What we’ve heard from people who have near death experiences is that they often can hear at some level. It’s as though they are inside a house. When they’re not too sick, they can answer the front door and talk with you. But as they get sicker, they move to rooms farther and farther back in the house. They may be able to recognize your voice, and hear your words, but are unable to come to the front door to respond.” Pause. Then, “You should talk to your dad. On some level, he may be listening.”

We also try and remember the patient when he was a vibrant individual, often by telling stories. Chaplains seem to have the best knack for this. Docs tend to get caught up in the medical details of the imminent death and pathophysiologic changes that led to this point. Transitioning to story telling can be challenging for us.

And bringing the patient into the room can be hard for new fellows. Though they are beginner palliative care fellows, they are also expert residents. It’s sometimes hard to unlearn patterns of communication based on medicalese, rather than person-to-person relationships.

Cultivating a beginner’s mind takes attention and practice.

by: Alex Smith @alexsmithmd