A fascinating study by Zachary Goldberger and colleagues was just published in the Lancet. The study gave us some good data on the bad outcomes of CPR in hospitalized patients, and brought up some challenging results on whether hospitals that attempt resuscitation for longer periods of time are more likely to have patients survive to discharge.

Brief Run Down on What They Did

The authors used the American Heart Association’s Get with the Guidelines-Resuscitation registry to look at 93,535 patients aged 18 years or older whose hospital course was complicated by an in-hospital cardiac arrest.

The authors excluded patients with cardiac defibrillators, and patients whose cardiac arrests occurred in settings that are often the atypical cardiac arrests in hospitalized settings. These included 18,604 arrests in ERs, ORs, post-op areas, procedure areas like cardiac catheter and EP labs, rehab areas, and those where the cardiac arrest location was unknown or missing. They also excluded those whose cardiac arrests lasted less than 2 minutes to “avoid inclusion of so-called partial resuscitations.”

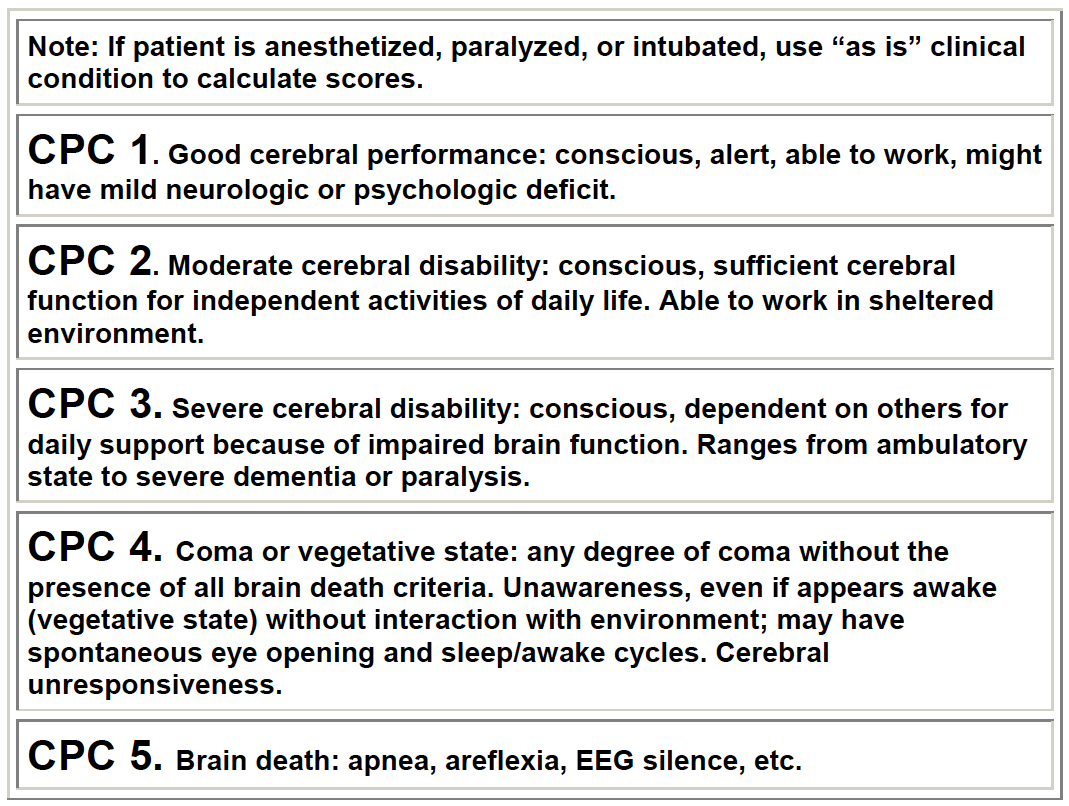

The heart of any study looking at CPR lies in the study endpoints. Relying on return of spontaneous circulation is rather meaningless if everyone is going to die in the next day or two in the ICU. The authors did include this as a primary endpoint, but also survival to hospital discharge. But again, who cares if everyone who survives will have significant impairment in his or her cognitive or functional status. To address this issue, the authors classified the neurological status of patients who survived to discharge into 5 groups based on the cerebral performance categories (see picture below) measured at the time of hospital discharge. What was considered “favourable”? CPC of 1 or 2. What does this mean in real life cognitive status and functional status? I have no idea considering there weren’t any real hard objective measures like a real cognitive screen used by the researchers, but I’ll go with it for now.

What They Found

Among the 64,339 patients who had a cardiac arrest that lasted at least 2 minutes, the authors found:

- Most (80%) had either pulseless electrical activity or asystole

- Nearly half (49%) achieved return of spontaneous circulation

- Few (15%) survived to discharge with a mean hospital stay after return of spontaneous circulation of two weeks (16.6 days)

- Even fewer who survived to discharge and had assessments of cerebral performance category in the favorable range (CPC of ≤2) with no difference based on resuscitation duration

The primary goal of the study though was to assess whether a hospital’s overall propensity for long resuscitation efforts in non-survivors of cardiac arrest was associated with outcomes in those who did survive arrest. The authors specifically chose non-survivors instead of the whole cohort as they postulated that a hospital’s overall propensity for long resuscitation efforts would be best seen if they looked at this group only. After adjusting for a whole lot of factors, patients who had cardiac arrests at hospitals with longer median resuscitation durations were:

- More likely to achieve return of spontaneous circulation

- More likely to survive to discharge

- Just as likely to be discharged with a favorable neurological status as those hospitals with shorter resuscitation durations

The Take Home

The authors state that these findings suggest “efforts to systematically increase the duration of resuscitation could improve survival in this high-risk population.” I’m not really convinced that this is true based on the findings of this observational study, but more importantly I’m not sure the results show that it matters.

First, we don’t really know if it was longer CPR times that contributed to better rates in returning spontaneous circulation or survival to discharge, or if it was some other unmeasured variable that may have resulted in real or perceived improved survival rates (see Ken’s post on coffee for a good example of confounding). Second, and more importantly, we also don’t really know what happened to these folks the second they step out of the hospital. And in the end, the rates of survival to discharge with a favorable neurologic state were the same in all hospitals independent of propensity for longer resuscitation duration.

My take home is that the odds are low of a truly successful outcome to CPR, as only 12% of hospitalized individuals undergoing CPR for longer than 2 minutes survived to discharge with a “favorable neurologic outcome.” It also looks like going to a hospital with longer CPR durations doesn’t seem to change this sobering fact.

by: Eric Widera (@ewidera)