In the early 1990’s, California Medical Facility (CMF) created one of the nation’s first licensed hospice units inside a prison. This 17-bed unit serves inmates from all over the state who are approaching the end of their lives. A few are let out early on compassionate release. Many are there until they die.

Today’s podcast is part one of a two-part podcast where we spend a day at CMF, a medium security prison located about halfway between San Francisco and Sacramento, and the hospice unit housed inside its walls.

We start off part one by interviewing Michele DiTomas, who has been the longstanding Medical Director of the Hospice unit and currently is also the Chief Medical Executive for the Palliative care Initiative with the California Correctional Healthcare Services. We talk about the history of the hospice unit, including how it was initially set up to care for young men dying of AIDS, but now cares for a very different demographic – the rapidly aging prison population. We also talk about the eligibility for the unit, what makes it run including the interdisciplinary team and the inmate peer workers, and the topic of compassionate release.

We start off part one by interviewing Michele DiTomas, who has been the longstanding Medical Director of the Hospice unit and currently is also the Chief Medical Executive for the Palliative care Initiative with the California Correctional Healthcare Services. We talk about the history of the hospice unit, including how it was initially set up to care for young men dying of AIDS, but now cares for a very different demographic – the rapidly aging prison population. We also talk about the eligibility for the unit, what makes it run including the interdisciplinary team and the inmate peer workers, and the topic of compassionate release.

Afterwards, we chat with the prison’s chaplain, Keith Knauf. Keith per many reports, is the heart and sole of the hospice unit and oversees the Pastoral Care Workers. These are inmates that volunteer to work in the hospice unit, serving a mission that “no prisoner dies alone.” We chat with Keith about how hospice in prison is different and similar to community hospice work, the selection process and role of the peer support workers, the role of forgiveness and spirituality in the care of dying inmates, and what makes this work both rewarding and hard.

Afterwards, we chat with the prison’s chaplain, Keith Knauf. Keith per many reports, is the heart and sole of the hospice unit and oversees the Pastoral Care Workers. These are inmates that volunteer to work in the hospice unit, serving a mission that “no prisoner dies alone.” We chat with Keith about how hospice in prison is different and similar to community hospice work, the selection process and role of the peer support workers, the role of forgiveness and spirituality in the care of dying inmates, and what makes this work both rewarding and hard.

Part two of the podcast, which comes next week, is solely focused on the Pastoral Care Workers. We interview three of them in the hospice unit and take a little tour of the hospice gardens.

Eric: Welcome to the GeriPal podcast. This is Eric Widera.

Alex: This is Alex Smith.

Eric: And Alex, this is not my office.

Alex: This is not your office. No.

Eric: Where are we?

Alex: We are in the California Medical Facility and we will ask our guest about that.

Eric: Yes.

Alex: What this is, where are we? Our guest today, we’re delighted to welcome Michele DiTomas, who is a friend. I’ve known Michele a long time, since the Joint Medical Program. Shout out to the UC Berkeley-USCF Joint Medical Program. And she is now Chief Medical Executive for the Palliative Care Initiative with the California Correctional Healthcare Services. Did I get that close?

Michele: That was perfect.

Alex: That was perfect.

Michele: Yep.

Alex: Great. Welcome to the GeriPal podcast, Michele.

Michele: Thank you for having me.

Eric: And you’re also the medical director of the hospice unit here.

Michele: Yep. Through a series of events, I started working as a consultant to the Department of Corrections in around 2006, and I was assigned to the California Medical Facility. And we have a 17-bed inpatient hospice that serves men from throughout the state of California who choose to have comfort-focused treatment at the end of their lives. And it’s an incredibly compelling place to work. Lots of closure, reconciliation, forgiveness, peer supports. It’s a real moment of humanity inside of a justice system that sometimes doesn’t always have that touch.

Eric: Yeah.

Alex: Mm-hmm.

Eric: So I’m excited because we’re going to be interviewing Michele, but we’re also going to be interviewing others, including inmate volunteers here, chaplains.

Alex: Mm-hmm.

Eric: We got a lot to talk about in this podcast about hospice in prison, but before we do, we always start off with a song request. You got a song request for Alex.

Michele: I do. Bonnie Raitt was inspired by the work that our peer volunteers do in this space, and it’s called Down the Hall.

Eric: Wait, so Bonnie Raitt sang a song about hospice in prison?

Michele: Yeah, so in May of 2018, there was an article by Suleika Jaouad in the New York Times Magazine, and they spent about two weeks in our hospice with us learning about the work that’s done. And what she found most compelling was the work of the peer workers. And so the article focuses on the work of these three men who were mostly gang involved and did something really bad when they were young. And through the journey of rehabilitation, they became very different people and they wanted to give back. And these jobs in our hospice are one of the few places that you can have really meaningful work within the incarcerated setting. So the story of these men giving back and getting to a new place in their lives was very compelling. And so Bonnie read about that story and it inspired her to write this song.

Alex: And it won a Grammy.

Michele: And, well, the album-

Alex: The album won a Grammy.

Michele: The album won a Grammy …

Alex: Yeah.

Eric: How long ago was this?

Alex: A few years back.

Eric: A few years?

Alex: Yeah.

Eric: Because that article wasn’t too long ago. It must have been a few years, right?

Michele: The article was 2018, but I think Bonnie read the article more recently. And the Grammy was just a couple months ago, actually.

Alex: Oh, a couple months ago?

Michele: Yeah.

Alex: Wow. Okay. Here’s a little bit.

(singing)

Eric: That was lovely.

I’m going to just start off, if we can go a little bit back in time, and you can just tell me, how did this all start?

Michele: Yeah. So this, really, this space grew out of the HIV epidemic. So in the late ’80s, there were many, many people, especially men inside of the prison system, who were dying of HIV. And at that point, there were signs up, literally said infectious disease, do not enter, danger. Healthcare staff were afraid of patients with HIV because there wasn’t clarity on how it was transmitted. So if healthcare staff are concerned, custodial staff are concerned, the other incarcerated people. So these men were extremely isolated, and they were dying alone.

And so Elisabeth Kübler-Ross heard about this situation and she ended up coming to CMF to visit with some of her volunteers. And that grew into a group of volunteers coming back and at least providing support groups, giving those men a place where they could talk at least. And then from that, through community activists, ACT UP, legislators who felt that there needed to be something done, doctors within CDCR who cared passionately about the HIV population and others, all came together and we were able to eventually get funding for this 17-bed inpatient hospice.

So here we are. And the first year that it was opened, around ’94, I think 56 men died of HIV in this building. And it continued for years, but now with the treatment, it’s transitioned. So in 2010, there were about 150,000 incarcerated people in California. Those numbers have come down dramatically to about 100,000 at this point. So we’ve gone from 150,000 to 100,000. But when we look at people over the age of 55, 55 and older, we had about 11,000 in 2010, and now we have 18,000 people aged 55 and older.

Eric: Wow. Yeah.

Michele: So that number’s really growing. And people are getting life sentences. They’re going to get older, they’re going to struggle with geriatric conditions, and they’re going to need palliative services and eventually end-of-life care. So who we have now are, you know, I have had one case of HIV in 17 years of working here. The person didn’t believe in the medications. But now we have older people dying of older people illnesses. Cancer, end organ disease, sometimes dementia, things like that.

Eric: Mm-hmm. And where do these people that come to this hospice unit, where are they coming from?

Michele: So they can be men incarcerated anywhere in California. So we have such a large population of incarcerated people. There’s about 33 prisons, the majority of which are for men. Only about 5% of the population is female. So they can be referred by their primary care doctor or to us. It’s by choice, just like in the community. You can choose comfort-focused care or you can choose to continue chemotherapy. We really like the community doctors to know, so those of you listening, that our patients, they’ve lost their physical freedom, but they have autonomy in terms of their medical decision-making just like anybody else.

Alex: And are the regulations similar or different in terms of six month required prognosis or less, should the disease take its usual course, or illnesses leading to a short prognosis? That’s one. And you’ve already said that the goals have to align, but I wonder if there are differences here with… Are you allowed some more flexibility-

Michele: Yeah.

Alex: … in other words, than you might be in a Medicare-regulated hospice facility?

Michele: Yeah, absolutely. I mean, I have 17 beds for the whole state, so I want to take care of my resource so that I’m available when people are in the last few days or weeks of life and really, really need that service. But we do choose people who have less than 6 to 12 months. But if somebody wants to continue a medication, and that’s sort of the deciding factor for them, with the Medi-Cal, Medicare, there’s restrictions that don’t allow me that flexibility. And in this system, I actually do have a little bit more flexibility, so that’s a plus.

Eric: So continuing potentially chemotherapy…

Michele: Yeah.

Eric: Dialysis? You guys do dialysis here?

Michele: So historically we did do dialysis here. So if somebody was dying of lung cancer, we’re not going to make them stop their dialysis. When they built a new prison hospital in Stockton, the dialysis went there. So now it actually is a little bit more challenging, because if patient wanted to come to hospice, they would theoretically give up their dialysis.

Eric: So in some ways, this is kind of like the VA, where you don’t have to follow Medicare guidelines, but you can actually actively do concurrent care for these individuals.

Michele: Yeah. We have that.

Alex: Mm-hmm.

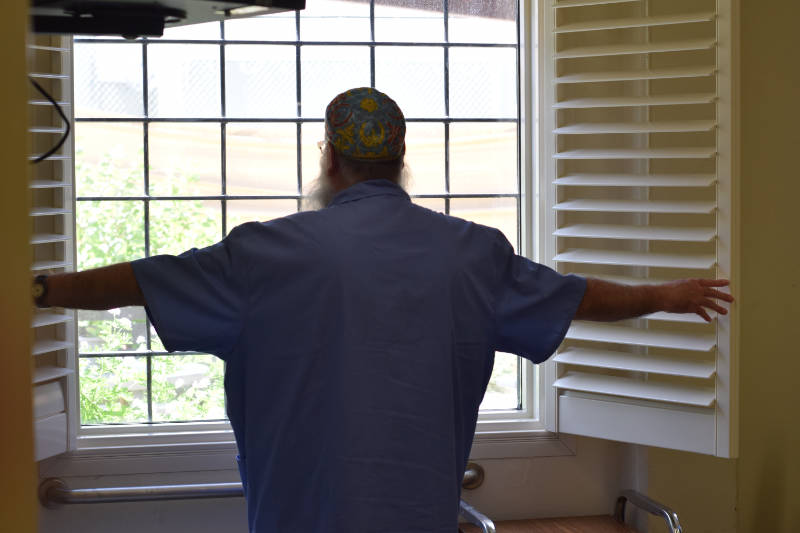

Eric: I’m going to take another step back if it’s okay. As we walked in here, this is a very big complex that we’re in. Can you give our listeners just a brief visual about what… or not a visual, I guess. This is all audio right now.

Alex: Right.

Eric: What is this complex that we’re in?

Michele: So, I mean, this is a prison, and it feels like a prison. You see more walkers, wheelchairs, more gray hair than you might expect, but there’s about 2000 men living in this space. It was built in 1955, so it wasn’t designed for a geriatric population. It’s like a long, I don’t know, almost like a quarter-mile centipede with legs, and the legs are the housing units, the medical units, inpatient mental health. We have about 450 inpatient mental health beds. We have about 100 skilled nursing facility-type beds for people who need assistance with their activities of daily living, who maybe have significant cognitive impairment and needs support.

But it really is… It’s a prison primarily. It wasn’t designed for older people. And when you think about the geriatric syndromes, think about being in a prison setting and not being able to hear what’s going on very well. You know, you could potentially get yourself in trouble. And so there’s developed a whole system of responding to this aging population. We have vests that men wear who are hearing-impaired that say “hearing impaired” on the back. So if an officer is yelling at them to get down or to stop and they don’t hear, they understand why. There’s vests that say “mobility impaired”, and that’s because you may have somebody who we have an alarm and they’re supposed to get down for the alarms on the ground, and then they have to stand back up after the alarm. But some older people might not be able to do that because of their mobility impairment. So it’s a way for staff to understand that they’re not being belligerent, but they’re not able.

Alex: And while we’re talking about the larger prison complex that we’re in, I want to just mention briefly that Bree Williams, who’s been on our podcast previously, helped to develop the prison-specific activities of daily living, which have things like, are you able to get up or down from your top bunk, right? Which is a better measure inside a facility like this, because that’s a common daily activity that you need to be able to do.

I wonder… And when we were talking earlier, you gave us a wonderful tour when we were in the skilled nursing facility. You were talking about also challenges people face with cognitive impairment or dementia and how that might represent a unique challenge in a prison system. For example, you mentioned somebody might steal, might take potato chips from somebody else and get in trouble, but they don’t have the memory to recognize that those are not their potato chips, for example.

Eric: And just for a visualization, as we were walking through the CMF, Michelle says, “Eric, your mouth is open.” [laughter]

Alex: Yeah, because you saw the locks on the doors.

Eric: I saw the locks on the doors.

Alex: Right.

Eric: Everything about this place is somewhat very familiar, but it’s, like, frame shifted by 30 degrees… It just, it’s different, and I’m still trying to grapple with it. Yeah.

Michele: Yeah. It is. The population’s aging, and so I’ve been here 15 years and I’ve seen it change. I’ve seen it become more debilitated. And there’s also a trend that I’ve seen more recently, is people coming into the system. So when we see the numbers of older people increasing, you’re thinking, oh, they have long sentences, of course they’re getting older, but it’s not just that. And the research isn’t really out there yet to understand exactly why the population is getting older.

But I have, anecdotally, in the last couple months, had two patients who committed their crime late in life. And then they entered. We did a MoCA on one. It was 13 out of 30.

Alex: Wow.

Michele: And that wasn’t part of the consideration. I mean, for both of these people, their crimes were… they were bad, but they were directly related to this new onset cognitive impairment. And I think we have to think about, as a society, are we providing enough social support in general for older people and for people who are having cognitive impairment so that they don’t end up in this situation and we don’t end up with… You know, they both had a victim of their crime. How could we have prevented that upstream? Because these weren’t people who had a life history of violence.

Alex: Right. Should we drill down to the hospice now?

Eric: Well, before we drill down to the hospice, general palliative care needs in the entire facility, or maybe just in prisons in general. What do you think about that?

Michele: So this year… I’ve been working in this hospice space for a long time, and we have some really best practices. And so my job this year, the last year and a half, has been to take some of those best practices and move them out to other spaces.

Eric: Great.

Michele: And some of it’s about changing the culture and the way we look at things. I can remember an incident when I first started working here where a demented patient pushed their tray, their food tray, as people with cognitive impairment do. The juice splashed onto the boot of an officer, and that falls under the category of assault. So, you know, you get a rules violation. You get written up for that. And we pushed back against that and explained, but it was some work to get to the place where that was understood that that’s part of the person’s medical complexity.

Fast forward 15 years, we had a patient with early-onset dementia who had very strong behavioral components. He was very, very impaired, but still mobile because he was younger. And he pushed, literally pushed a female officer, and she said, “Don’t worry about it. We know him. He’s very impaired.” And so that was a real culture shift from having to really push for some juice on a boot to someone being part of the overall team and really having integrated and understand the complexity of the patients that we’re working with.

So I think taking some of that culture that’s grown up in this facility, because we do so much of it and expanding it out. So wanting to offer people, as people age, there’s something called desistence, and they… You sort of age out of your criminal thinking and you come to a different place. And I think as people get to the end of their life, they’re reflecting back on their life. They’re doing legacy building. They’re thinking about what were the things that were positive. And that happens in this setting too. So many times people want to have reconciliation. They want to have closure. They want to have forgiveness. In many cases, the families were the victims of the crime. If not the victim of the crime, they were certainly the victim of the incarceration. They suffered from it. They didn’t have a mentor, a financial provider, all of those things. So being able to create a space through palliative care to allow people spiritual support, access to their families, having people available, a medical social worker to help them track down a family that might have been lost, and to be able to allow them to reach out to the family and say, “I’m sorry about how this impacted you,” and maybe be able to find some closure and forgiveness. I don’t know if the chaplain shared with you stories about…

Alex: Well, that’s going to be coming up.

Eric: Yeah.

Michele: Okay.

Eric: Right. We’re re-sequencing from the order in which we recorded. No, no, that’s good. I want to just follow up on that briefly before we get to the hospice piece. What is the current state of palliative care outside of hospice within the California prison system? Are there outpatient palliative care clinicians? Are there multidisciplinary palliative care teams? No. I’m seeing some… Yeah.

Michele: There’s a 30-bed palliative care unit at one other facility. What we’ve been doing in the last year is really building up a palliative care service for women, because there’s less women who are… Overall, there’s less women dying. It’s hard to have a brick-and-mortar space for such a small number, and yet they require services. So we’re designing a program where it won’t matter on what the housing is. It’ll be more like a hospitalist service where you may be living on the main line, but have a diagnosis of cancer, be getting chemotherapy, and really need some of these supportive services, some support and advanced care planning, identifying a surrogate, reaching out and finding correct phone numbers for that person, getting a chaplain to come and visit, getting peer support workers around you so that you can have the emotional support that you need.

Eric: A naive question. If they’re getting things like chemotherapy, what does that… Do they go somewhere else for the chemotherapy, and what does that look like?

Michele: So the patients within the Department of Corrections, there are doctors at every facility. There are clinics. Everybody has a primary care doctor, a primary care nurse, a team. But if the services that they require aren’t able to be provided within, they have Health Net as their insurance, so we contract with specialists in the community. If they need an acute hospitalization, they would be hospitalized in a hospital that we contract with. If the community hospital isn’t able to provide a service like tertiary care, oncology care, they would get a referral to UCSF or wherever, just like anybody in the community. But the cost to society is higher because they have to be escorted by an officer. They have to have somebody sitting at their room watching them while they’re there.

Alex: Mm-hmm. I wanted to ask about… Can we turn to the hospice?

Eric: Yeah.

Alex: What makes this place run? We saw the interdisciplinary team. There’s a big team. This is great. It just warmed my heart, and it was so familiar in so many ways. As Eric said, somewhat frame shifted, but I wonder if you could just for our listeners, sort of paint a picture of who all is here supporting this 17-bed unit.

Michele: Yeah. So we’re hoping to have, as the population ages, we need more of these support people at other places. But right now at our facility, we have a chaplain, who’s sort of the heart and soul of the program. He provides spiritual support to the patients, to the staff, and to the peer workers. So another big component of this program is, just like hospice volunteers in the community, we have hospice volunteers/workers who are peers from the incarcerated population who receive extensive training on how to sit with people, how to communicate, how to listen, how to protect themselves upon from the grief and loss that comes from this job. Because we have 60 to 70 people die every year in this building, and so we want to support those men and staff as well. We have nurses who have extra training in palliative care. We have doctors who we provide training to for this. We have a psychiatrist. We have a dietician. We have medical social workers who support the patients. And we’ve really tried to serve that hospice mission of serving the patient and the family. And so not all of our patients still have friends or family in the community because they’ve been incarcerated for so long. But when they do, we really want to bring those people into the story and provide them support as well.

Eric: What does visitation look like for them?

Michele: So visitation here is much different than a typical prison visit where you’re kind of in a room, you feel watched, there’s a lot of restrictions. In this space, it’s really normalized. You walk through that door and you feel like you’ve come into more of a nursing home. The doors aren’t locked. There’s a visiting space where you can come and watch a movie with your loved one. They could go into the patient’s room, sit on the bed with them, hold their hand. They can stroll out into… We have a beautiful garden space for family. We’ve had people get married in the garden. We’ve had baptisms. When children are allowed to come `in… There’s a lot more exceptions. If we had a patient who was dying and his mother had a history of a felony, and so typically by policy, that person wouldn’t come in to a visit. But in this setting, those things will be looked at on a case by case basis and almost always approved by the warden so that people can be there with their loved ones.

Eric: Do people ever leave here alive?

Michele: Well, certainly. I think even with experts, 10 experts, we’re going to have one or two people who outlive the expectations. And it’s a little bit even more true in this setting, because it is so supportive. We definitely have people who were dwindling and really looking like they were coming to the end of life, and when they start getting these supportive services, they pop back up. And that’s what we want to be able to provide statewide. We really want to be able to… Any facility that has medical beds where people who are aging, having these chronic long-term diseases are, we want to be able to provide them these same supports.

So it may not be a hospice, but it’s a social worker who can help them get a video visit, who can track down their daughter. We just had a gentleman who hasn’t seen his family in, I think, 50 years. He struggled with mental illness, substance use disorder. He was living on the streets. He had come from another state. And within 24 hours, our chaplain was able to track down his ex-wife. He’s had video visits with his four children. He’s met his grandchildren for the first time. He has significant cognitive impairment, but he is very much enjoying this. And not only is he enjoying it, his daughters who had never had a connection with their father have had this whole new experience that’s really changed their… You know, it changed their life.

Alex: Mm-hmm. The other issue that came up frequently in the IDT meeting was compassionate release. Some patients trying to get compassionate release, some patients trying to get released but don’t have a place to go to, some patients who decided not to be released because that meant that it was easier to family for family to visit them here than for them to be released.

But this is, getting back to your question, Eric, another way that people leave this hospice, that doesn’t happen in our hospice, for example. I wonder if you could say more about compassionate release, the sort of state of that in general, how you interact with that and the challenges that you face in helping people obtain compassionate release.

Michele: Yeah, I mean, that’s, I’d say, something I felt really passionately about for decades and the legislation has changed, so the laws have changed over the last 15 years. It used to be you had to have less than six months’ prognosis before you could submit somebody. But there were so many hoops to go through. The process took four to six months, so we almost never got people out before they passed.

Now, the legislation has changed several times. The criteria are an end-of-life trajectory. So if somebody has metastatic lung cancer and are on palliative chemo, they still have an end-of-life trajectory, so we can move forward earlier. We also all know that doctors are overly optimistic when it comes to these things. So if a doctor says you have less than six months, you probably have two months. So we were really coming to this really late in the game.

So with these changes, along with implementation within CDCR, I have a tracking tool, so they still have to run through hoops, but now I know I have a tool I can pull up statewide where people are in this compassionate release process, and if it gets hung up or stopped, we can have an intervention to figure out how to get it back on track.

So at this point, some of the hoops have been removed, the timeframes have been expanded, and we’re really expediting the process. So I’d say it’s about a two-month process now. It goes from if they meet medical criteria, it goes directly back to the sentencing court, and then we have open communication with the courts so that we can provide medical information. The problem is you can’t even apply for this if you don’t have a place to go. So unless you have family that has the resources to bring in a person who’s dying at the end of the life, you can’t move forward with the process.

Alex: And we heard a lot during the IDT meeting. Compassionate release, I guess CR is the word I was hearing, was brought up a lot. Is there an option of going to… because it sounded like there was an option of going to a skilled nursing facility. No,

Michele: No. I mean, we have a few nursing homes who maybe the director has a personal connection to justice-involved individuals and has a reason that they want to for social… be social-minded and accept some of our patients. But there’s only a few places, and we have worked really hard to find skilled nursing facilities who are able to not only just accept Medi-Cal, but overcome the stigma of people with a criminal record. So it can be really challenging

Eric: There may be a couple listening to you right now.

Michele: Yeah, that’s what I’m hoping.

Eric: Is there any word you want to give to them?

Michele: Our patients are… They’re lovely. They’re at a place in their life where they just want to… I had one guy who wanted to go home and eat a homegrown tomato in his sister’s backyard. And you know what he did? He went home. He sat with his family for a couple weeks. He ate scrambled eggs and some homegrown tomatoes in his backyard, and died with his family around him. So we had a patient who… A nursing home outside of Sacramento agreed to accept one of our patients and said, “Well, we’ll take this patient, but we’re not taking another one for 6 to 12 months.” I was like, okay, fine. So they took this gentleman. He had end-stage pulmonary disease. His family came and visited him in the nursing home every day for seven days, brought him a delicious, home-cooked meal every day. The nursing home was so happy to see the way this family interacted and that they were able to provide that to the family, when he passed, they called me and they said, “Okay, we have an open bed. You can send somebody else.”

Eric: Wow.

Michele: So they really understood that they weren’t just giving something to the patient. They were able to give something to this whole family, to his daughters, to his sisters. So when we’ve gotten people to accept our patients, they find reward and fulfillment as well.

Eric: I can imagine this is a very rewarding and fulfilling job for you. But before I ask that question, when you think about what’s the hardest aspects of this job as a physician, as a medical director, what would that be?

Michele: I mean, we are talking about compassionate release. It’s really hard when people that, as staff, we’ve gotten to know them over a long period of time. We know their behavior. We know what’s inside their hearts. And it’s hard for a court or a parole board to see that in a very brief hearing. And sometimes when people end up dying here and have families that really wanted them to be with them at the end of life, that can be disheartening for staff. But then we have somebody who we worked really hard to get out and we get back from the family that he went out, he sat on the couch and watched This Old House and Antique Roadshow with his 13-year-old daughter for the two weeks before he died. And we feel like that was great for Mr. Kay. But to me, that 13-year-old daughter now has a story that doesn’t involve “my dad died in prison”. Her story is, “I was able to sit with my dad as he died of cancer and be part of his end-of-life experience.”

Eric: I also noticed, so I’m just going to… We had a chance to hang out with Michele before this interview. As we walk down, is there a name for that long… I’m learning different names in prison like Sally Port, which is something I’ve never heard of before. Did I say that right? Sally Port.

Michele: You did. Sally Port.

Eric: Is there a name for that long corridor that we walk down?

Michele: The main line.

Eric: The main line. So we’re walking down the main line. Every 15 feet, you were getting stopped by people. One person saying that he was leaving this place-

Michele: Yep.

Eric: … and another person who was going up to the parole board. I am actually just getting emotional thinking about it. That must be both… I don’t know. It must be incredibly emotional just walking down there and talking to these people as… Yeah, I just want to get your thoughts.

Michele: I mean, I’ve been here a long time, and a lot of these men have been here a really long time so I know them pretty well. The one man you mentioned, he had just gotten granted by the parole board. He had a walker. He had one of those vests on that said “visually impaired” on the back of them. He had his mask on even though we’re not required to mask at this point. He’s wearing his mask because he is old and vulnerable and he wants to get the heck out of here. So he was finally granted by the parole board and then upheld by the governor, and so he will get to go home.

I think in the last decade, historically, the parole board, even if you had a chance at getting paroled, it wasn’t a very common occurrence. In the last 10 years, the parole board has changed some of their risk assessment processes and there are getting more people, we’re seeing more lifers who are getting approved. I would hope that we will continue to move in that direction, because these men really aren’t a risk to public safety anymore. They’re very, very, very low risk, and yet they cost the state a lot of money. These older patients are costing a ton in healthcare costs. They’re costing a lot in terms of custodial supervision when they’re at an outside hospital. So it’s the high cost of low risk at this point, and I think we could be using those resources to prevent crime in the first place.

Eric: Well, I want to thank you, but before I end, we always ask a magic wand question. If you had a magic wand, what one thing would you change? Now, I’m going to narrow it for you around hospice and palliative care in prison.

Michele: I mean, if I had a magic wand, I would want us to be able to take what we learn about our patients. There’s this whole Scandinavian model where a lot of the safety and security comes from not from locking people up or putting on shackles or locking a door, but from getting to know them and communicating with them and mutual respect. It’s called dynamic security, as opposed to static security. My dream would be that we do more of that, so that we really know these older people, and the people who are making decisions about whether they’re going to be safe or not to return to society are people who really know them, are people who really have a good, deep understanding of their risk. Because I feel like as a medical provider of taking care of somebody, the man in the hallway, I’ve known that person for 15 years. I think that I wish there was a way that we could put that knowledge into the decision-making process, because I think it would change for a lot of people.

Eric: Well, I want to thank you again for joining us and for the wonderful tour. For the folks listening, we will have pictures up on our website so you can see the hospice unit and the garden and links to other things, so check out the website.

And we have more coming up. We’ll be interviewing chaplain, inmates here who volunteer, so keep on listening. We may split this into a two-part series. We’ll decide about that, but stay tuned.

Well, that was a moving and… I mean, I learned a lot from Michelle. Alex, how about we move on? Who’s the next person we interviewed?

Alex: Our next guest is known as Chaplain Keith, and he’s worked at the hospice unit in the prison for the longest time of anybody we interviewed. In fact, he was there around the time that it started during the AIDS epidemic.

Eric: So-

Alex: And we ask him about that. He also, of note, we learned in the interdisciplinary team meeting that we attended beforehand, that he’s such an integral part of the team and is nearing retirement age that they are trying to manualize Chaplain Keith by creating a series of 15 modules about his approach to palliative care hospice chaplaincy.

Eric: So let’s hear his story.

Thanks for joining us today. Can I have your name again?

Keith: My name is Chaplain Keith Knauf.

Eric: And Keith, is it okay if I call you Keith?

Keith: Sure.

Eric: What do you do here in the hospice unit?

Keith: Well, I’m the chaplain, so I’m the director of pastoral care and work with selecting the pastoral care workers. Those are inmate workers who will provide companionship, spiritual support to all of our patients and make sure that our patients don’t die alone unless they want to. I think in my 27 years here, there’ve only been maybe two that really didn’t want to have anybody with them when they died. Both of them were Buddhists and they wanted to be mindful of themselves and not have any interruptions in that transition. But everybody else, they want somebody with them to hold their hand, to be there for them.

Eric: And how long have you worked here?

Keith: 27 years.

Eric: What motivated you to start working here?

Keith: Well, I had a background as a psych tech and also as an orderly. And I was in the ministry for a while, little place north of town called Winters. And I’d been there for seven and a half years. And then during the AIDS pandemic, this position opened up and I thought, well, maybe God might be leading this way, because I worked with the Yolo County Hospice and also with the Yolo County… When there were transients that died or they just couldn’t identify somebody, I would do the memorial services and be there for the community, so I was like a community pastor. So when this position opened up, I applied, and I’ve been here ever since.

Eric: You know, the funny thing is is we were able to listen into the IDT, and it’s in some ways very, very similar but in some ways very, very different than what I do in my own hospice work. And I wonder, how do you think it’s kind of similar and different from the work that happens like in Yolo Hospice?

Keith: Well, hospice on the outside, you don’t have the custody hoops to jump through. So you can do just about everything here, but you have to do it within the realm of custody and getting the right forms done. And for instance, if you want to donate Bibles or if you want to donate whatever to the hospice program, you have to fill out five pages of forms. But on the outside, you just donate it. It’s not a big deal. So you just get the approval from the administrator, “I want to donate this radio”, and, okay, fine, bring the radio in, and then it’s donated. But here, you got to go through a lot of hoops, get signatures up to the warden to donate anything.

Eric: And part of it, mission sounds like nobody dies alone-

Keith: Right.

Eric: … if they don’t want to.

Keith: Mm-hmm.

Eric: I’m guessing that that requires a fair amount of volunteer support for that.

Keith: Incredible amount, yeah. So that’s the other thing that’s different if you’re still talking about differences. On the outside, most people die alone. Within the institution, they don’t have to die alone because I have a group of 25 pastoral care inmate workers that we’ve hand-selected, and they make sure that people don’t die alone, so they take shifts with the patients.

Alex: How do you select who goes into that program?

Keith: There’s a 10- to 12-point selection process, and I won’t go into all the details of that, but we want to make sure that the inmates are programming well.

Alex: Can I ask what programming means?

Keith: Programming means you don’t have rules violations. So if they have a rules violation, well, I’m a fat chaplain. Would you trust me in a malt shop? No. So we have inmates that have some drug backgrounds. Would you trust them in a hospice? Probably not. So one of the criteria is if they’ve been drug free for five years, then we’ll consider them and bring them into the program. If not, well, no, then they’d be denied. We also look at their mental health. So if they’ve had, for instance, a suicide attempt in the past, and if there’s some kind of mental illness, then we’re looking at them very carefully because they’re going to experience serial death here, and would this be the right place for them?

So there’s all these criteria that are custody-minded and also psychosocial-minded. And I try to balance things out psychospiritually too. So I have Muslims who are in our group, inmate Muslims, and that way they can, when there’s a Muslim inmate that passes, they can do the Ghusl Mayyit washing ceremony. I have a Jewish inmate who is really good with Tahara washing ceremonies at a time of a Jewish passing. We have Native Americans. So I try to balance everything out in terms of their culture, their ethnicity, try to get a good balance so they can have their brothers and spiritual-minded people next to them.

Alex: Is this the notion of the vigil we heard about during the IDT?

Keith: Yes.

Alex: What is the vigil?

Keith: A vigil is when a doc thinks that somebody may have 72 hours or less to live. And as you know, it’s a guess. Only God knows. And I love it when the docs are wrong and they live for three or four weeks or months. But usually the docs have it down pretty good, and they start seeing a decline in their breathing, or their kidneys aren’t working. There’s some failure. And then at that particular point, we get our hospice pastoral care workers to sit with the patient and they provide companionship and spiritual support. The family’s also contacted at that time. Our social workers and myself, we work really hard to get the families in here to visit, and custody cooperates with all that. And we’ve had people here visiting who have had warrants out for their arrest, and custody will still let them in and under supervision so they can be with their loved one when they die.

Alex: And they’re not arrested when they’re visiting.

Keith: As far as I know. I don’t know if they call the sheriff after, but at least they’re allowed to come in and visit.

Alex: That’s great. So there are exceptions made around that time.

Keith: Exceptions are made, yeah.

Alex: Yeah. I want to ask you, Keith, about the role of forgiveness. And certainly community chaplains, we’ve talked with other chaplains on our podcast, about the importance of getting your spiritual affairs in order for many people near the end of life. For many people, it’s important to get right with God, for example, and I would imagine that would all be all the more pressing here for incarcerated persons. I wonder if you could talk about that, not just in terms of that reconciliation with their faith and with their religious or spiritual beliefs, but maybe also with that sense of connection with their family and things they may have done.

Keith: Yeah. There’s one story that we tell quite a lot, and that’s a story about five daughters. And these five daughters had a dad, and the dad killed the mom in front of them at the dinner table. And the dad just totally lost control, major anger management issues. And in that one fell swoop, they lost their mom. Of course, she was murdered in front of them, and their dad too, because then he was incarcerated.

Fortunately, the mother’s brother took all five girls in and raised them amazing. They were real solid Christians, Orthodox, Eastern Orthodox Christians. And when their dad arrived to our hospice, their dad wanted to contact them, and that took a little bit of doing just to find them. I had to do that through the bishop of the Eastern Orthodox church. And the bishop asked them if they would like to visit their dad for a time of reconciliation and also for closure for themselves.

So it was a bit of a process to get all of that put together. We were concerned for the ladies. Now that they’re ladies, they’ve had kids. A lot of them had gone through college, were college grads and really good jobs. But they wanted that closure. And so we set up a time, and I’m told not to go too far into this whole story, but it was in this very room. And we set up this time and I had him sitting on one end of the room. They were on the other. Had him by the door in case they felt uncomfortable. It was all about them. And they brought pictures of their kids, he didn’t know that he had grandkids, and they had a nice chat with him. It was really a heavy, deep conversation. And they forgave him.

Alex: Wow.

Keith: And that was totally amazing. I think he was amazed at the whole thing. So they went back to their church. And they had gone through a lot of counseling, professional counseling, as well as support from their Eastern Orthodox church. It was an amazing thing. It was something to behold.

Alex: Right, what a gift that they gave him.

Keith: Mm-hmm. Yes. Mm-hmm.

Alex: That forgiveness after such a heinous act.

Keith: Right. And he was sorry. He expressed his sorrow for totally disrupting their lives. So it was back and forth on that. Gave him an opportunity to release some of that as well.

Alex: Mm-hmm. I also wanted to ask you, I think you may have started here 27 years ago.

Keith: Mm-hmm.

Alex: Was that during the AIDS epidemic?

Keith: That was during the AIDS pandemic. Yes, it was. My first year here, we had 72 deaths due to AIDS.

Alex: 72 deaths due to AIDS.

Keith: Yeah, that was… and then all the cancer as well. And so I had a memorial service every month. It was a pretty intense time.

Alex: Like a group memorial service.

Keith: Yeah, we had that in the chapels.

Alex: I can imagine.

Eric: And who attends those memorial services?

Keith: Well, the families weren’t allowed to attend here. The families would have memorial services on the outside. But there’s another aspect that a lot of people on the outside don’t think about, and that’s, when you’re incarcerated for 20 or 30 years, your family really becomes your fellow inmates that you’re housed with. And so the definition of family was broad. And so people from the outside can come and visit our hospice patients as well as their friends who are actual, in their minds, family members, maybe even closer than their biological family.

And so at our memorial services, these friends, these inmate friends, will come to the memorial service and cry, and they’ll share deep things about their friends who have passed and remember them in those ways. We also have… About a third of our inmates who die are veterans. And a lot of them had been honorably discharged. And so we can do everything except the gun salute. They don’t allow us to do that here. I joke about that, but we don’t do that. But we do have a flag folding ceremony for our vets, and we have… A lot of the veterans will come up and talk about their friend who died and the good service they did to our country when they were out.

Alex: Mm-hmm.

Eric: And can I ask you, when individuals come into the hospice unit, again, you mentioned that their family, their friend, their friends are their family that are here. Maybe for decades they’ve been here.

Keith: Yes. Yeah.

Eric: Does the chaplaincy also provide support to them, or can they visit the hospice unit, those individuals?

Keith: Yes. Yeah. The way we had it planned prior to COVID, now we’re hopefully going back to it, is Monday, Tuesday, and Wednesday, their inmate friends, their buddies, could come and visit. And then Thursday, Friday, Saturday, and Sunday was set aside for the biological family and friends from the outside. That’s the way we had it set up, and hopefully, we’ll, as I say, we’ll be going back to that. And we encourage that. So the patient then can have up to five close friends come and visit, and they can visit during the week, during those days, Monday through Friday. And it worked out really well.

Eric: What’s the hardest part about this job for you?

Keith: Hardest part? Oh, that was a question I haven’t been asked. I think maybe the hardest part is not being able to find family, because I work really hard at that, and not having the time to connect with a patient. So if a patient comes and we’ve only got them for three hours, that’s hard. That’s difficult. And then I don’t even have the time to try to find family or to work with them. Fortunately, we have our pastoral care workers who will be with them so they’re not alone. But I think that’s the hardest thing to not… I have a sense of closure too when they come, and if they give me three months, I can get all these things in a row and there’s a sense of fulfillment. But when it’s just three hours and they’re gone, that doesn’t give a whole lot of fulfillment. So that’s hard. That’s hard to deal with. Good question though. Thank you.

Alex: Last question from me.

Keith: Mm-hmm.

Alex: What’s most rewarding about this job?

Keith: Rewarding is when everything works together. And you find the families, they haven’t seen them in 20, 30 years, and it’s like… I suppose it’s like the hunter going out into the field and you got the animal in the sight, you shoot them, you bring them back, bring them back home. For me, it’s going out there, finding that family, giving them the opportunity for reconciliation, and then you bring them together and then there’s closure. They make amends. There’s reconciliation. And that also helps with reconciling with their faith with God. That’s a beautiful thing.

One more story real quick. We had a Vietnamese fellow here. He was a Purelander. I had no idea what a Purelander Buddhist was, and so I did some research on what that was. We found a Purelander monk who came in, got the mom here as well, and then he dies. And in the Purelander Buddhist way of thinking, your spirit still remains until you’re given leave. So that meant a flower, incense, and a prayer.

And when I found that out, the mom was totally distraught, not just because he had died, but because she thought he was going to be in prison through eternity. And so I was able to talk to the warden, and the warden approved her to come back. Even though his body wasn’t even there, she thought his spirit still was, as was her belief, and she was able to leave a flower on the bed where he died, and incense, and also she was able to give a prayer. And there was so much… She teared up, there was so much relief, and that was beautiful.

Alex: Yeah.

Keith: So things like that are very rewarding.

Alex: Thank you for the work you do.

Keith: Thanks for the questions.

Eric: I want to thank you for joining us today too. It was really a pleasure and really amazing work here.

Keith: Okay. Thank you.

Eric: So Alex, I think we’re going to split this up into two different episodes. So episode one, episode two of hospice in prison. What’s coming up in episode two, just for our listeners to be prepared for next week?

Alex: So in the first episode, we talked with Michele DiTomas, the Chief Medical Officer and also the visionary and leader in developing palliative care programs statewide in California prisons, and with Chaplain Keith. In the second episode, we’re going to talk with these pastoral care workers who are inmates who have been volunteering in the hospice for some time. And you’ll hear about how they keep vigil with patients in the hospice so that no one dies alone. Somebody is there 24/7. We also talk with them about larger issues, what is it like when you spend three-quarters of your life in prison for something you did when you were 17 years old, and opportunities for forgiveness, reform, and changes to the way the prison system is structured and focused.

Eric: I think it was one of the most moving GeriPal episodes we’ve done in a while, so please take a listen to our next GeriPal episode with these really remarkable people.