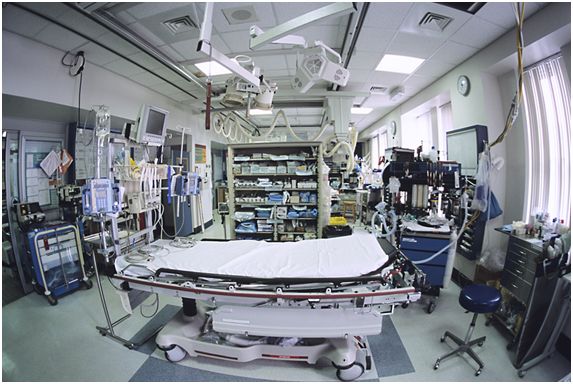

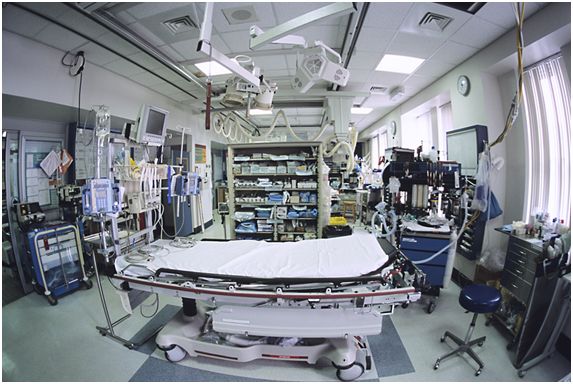

It is a story that happens all too frequently in a fragmented healthcare system. A woman with cancer on chemotherapy codes in the emergency room. Nobody knows her code status. The ER physician uses the skill and talent gained from years of training to successfully resuscitate her. The family arrives to let the physician know that the women had a DNR order. After discussions with the women’s oncologist and ICU team the family decided to not pursue dialysis and withdraw the ventilator. Disappointment sets in for the young physician as seemingly everyone gives up on his “save”.

It is hard not to feel bad for everyone in this story as heard on today’s NPRs morning edition. The woman who coded endured an ending to her life that she specifically asked to avoid. Her family had to both see the outcome of the code and be burdened by the resulting medical decisions. The ER physician, Dr. Boris Veysman, felt heartbreak that his efforts were not only in vain, but also undesired by all. His frustration at the outcome of the women’s case is palpable throughout this piece:

She died peacefully several hours later. The best resuscitation of my career turned into my most memorable professional disappointment.

I don’t blame Dr. Veysman for feeling this way. Blaming him would be akin to blaming the gas pedal for not braking. As an ER physician he did what he was supposed to do in this situation – resuscitate the patient if code status is unknown. What failed here is the advance care planning process in a fragmented healthcare system. There was a complete lack of a comprehensive approach to give patients their voices in emergent situations. I wonder how different things would have been if options like the POLST form was used in this case.

The lesson I learned from this essay is that resuscitation can be technically perfect yet fail the patient. This however, is a very different than the lesson Dr. Veysman gives his audience, which mostly falls in the simplistic don’t “give up” advice. It may be helpful for us all to turn to one of Dr. Veysmans earlier works to give us some perspective (Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:76):

If we are to let them go after so much has been done, were all our efforts in vain? So it often happens that we give birth to hope where there may have been none. But to the patients, that hope means more suffering.