The great resignation is upon us. One in five health-care workers has left their job since the pandemic started. Geriatrics and palliative care are not immune to this, nor are we immune to the burnout that is associated with providers leaving their jobs.

In today’s podcast, we talk with Janet Bull and Arif Kamal about what we can do to address burnout and increase resiliency, both from an institutional and individual perspective. Janet Bull is the Chief Medical Officer and Chief Innovations officer at Four Seasons Hospice and Arif Kamal is an oncologist, palliative care doctor and researcher at Duke.

We discuss Arif’s and Janet’s article published in JPSM on the prevalence and predictors of burnout among hospice and palliative care clinicians, as well as Arif’s Health Affairs article on the policy changes that are key to promoting sustainability and growth of specialty palliative care workforce. In that later article, Arif found that among many things:

- Burnout was reported by approximately one-third of physicians, nurses, social workers, and other respondents in the specialty of hospice and palliative care

- The presence of burnout was associated with increased odds of intending to leave early

If you want to learn more about what you can do to promote wellness on your team, check out this article Arif published with other colleagues in JPSM titled the “Top Ten Tips Palliative Care Clinicians Should Know about Implementing a Team Wellness Program.”

Eric

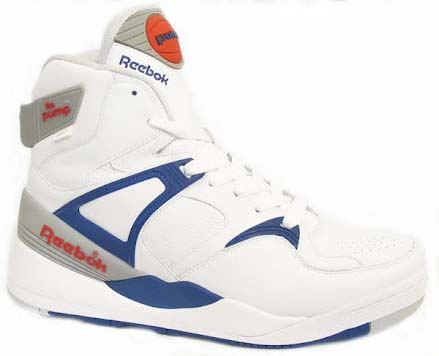

P.S. For those that are interested in the Reebok reference, these were one of my first Reebok shoes, the Pump (you squeezed the ball on the tongue to inflate the shoe)

Eric Widera: Welcome to the GeriPal Podcast, this is Eric Widera.

Alex Smith: This is Alex Smith.

Eric Widera: And Alex, who do we have with us today?

Alex Smith: Today from the great state of North Carolina, we are delighted to welcome two special guests. We have Janet Bull who is CMO Emeritus and Chief Innovation Officer of Four Seasons, a non-profit hospice and palliative care organization in western North Carolina. Welcome to the GeriPal Podcast, Janet.

Janet Bull: Oh, thank you both. It’s so great to be here with you guys.

Alex Smith: And we also welcome Arif Kamal, who’s Associate Professor of Medicine at Duke. Blue Devils recently beat Gonzaga in the basketball game, very important game.

Arif Kamal: That’s right. That’s right.

Alex Smith: And is an oncologist and palliative care researcher as well. Welcome to the GeriPal podcast, Arif.

Arif Kamal: Hey, thanks for having me. I presume this podcast is about men’s college basketball so I’m glad to be here.

Alex Smith: Yeah. I would also like to point out that the University of Michigan Wolverines finally beat Ohio State in football. I’m a Michigan alumni.

Eric Widera: I saw a lot of tweets about that. I had no idea what they were talking about. But this is not about college sports, this is about burnout, self-care and resiliency. But before we go into that topic, who has a song request for Alex?

Arif Kamal: Oh, I do. I do from the great state of North Carolina, Scotty McCreery.

Alex Smith: Scotty!

Arif Kamal: Great song… Five More Minutes, please.

Alex Smith: Five More Minutes. I saw Scotty McCreery. We used to watch American Idol religiously, and Scotty McCreery won it one of the years that we watched. Yeah, great singer, great country singer. I’m going to skip to the verse that’s very geriatric palliative care-ish, and I’ll do the other verse at the beginning…

Alex Smith: Also, I should say I broke my clavicle. So, for those of you watching on YouTube, my unique guitar positioning.

Alex Smith: (singing)

Janet Bull: Very good. I thought Arif was going to get up there and sing with you.

Arif Kamal: Aw, man, that touches me so deep, that song. I could listen to that all day long.

Eric Widera: Janet, I heard you had a different song request for Alex. What was that one?

Janet Bull: Yeah, mine was, I’m Going to Live Forever by Irene Cara. Just the juxtaposition, you know?

Arif Kamal: That’s great.

Janet Bull: Of when you get in those moments and you just feel like things are flying high.

Eric Widera: Alex, why did you pick that song?

Alex Smith: Well, I knew I had a better chance with Scotty McCreery.

Eric Widera: Okay. So we’re going to be on the topic of burnout and resiliency and self-care. I hear a lot about burnout lately especially, but I think back to a great article that you guys published back in 2016 about the prevalence of burnout in hospice and palliative care. Before we get into the topic, can one of you just describe, when hear burnout, what are we actually talking about?

Janet Bull: Sure. I’m happy to take this one. It’s a psychological state that results from prolonged stressors, job stressors, and it’s characterized by three things. The first is emotional exhaustion. The second is depersonalization, and they can tend to occur in this order, and then the third, it leads to a low sense of personal accomplishments. So we see those kind of three factors that make up the definition.

Eric Widera: And what is depersonalization?

Janet Bull: I kind of think of it as being cynical. It’s interesting because in some of studies of residencies, the first year residents are emotionally exhausted, but by the time they get to that third year, the rate of depersonalization is higher than emotional exhaustion. So, they become a little bit cynical just having that prolonged stress. We also see that when we look at burnout as, as people start overworking and they start not using their own resources because they’re working all the time. But…

Arif Kamal: Yeah. Yeah. I agree. I was on hospital service recently and for interns who are admitting patients, one of them said to me, “Man, this patient bounced back and man, that really stinks for me.” And I said, “You think that stinks for you? What about for the patient?” The idea is that somehow maybe the patient did this to somehow affect us. I was like, “A patient doesn’t care about how many admits you got that night or not.” Like, this person was in so much distress that they chose coming back here over the warmth of their own bed. That is something to pay attention to.

Arif Kamal: But that’s this subtle type of depersonalization where you start to believe that things are happening to and how they affect you only and not really sort of how they affect others. So, you start seeing that person as the bounce back, or the person that kept me from sleeping in the call room that night. You see them as this entity that’s actually out to get you versus what it really is, which is, “Oh, my gosh, there were in that much extremis that they, of all places to go, they came back here.”

Janet Bull: What’s interesting about that too is that when people have higher rates of burnout, there’s a higher rate of medical errors in hospitals and there’s lower cap scores. So, these have significant consequences.

Arif Kamal: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Eric Widera: And is resiliency just like the opposite side of the coin? Is it a different framework? What are we talking about when we’re mentioning resilience?

Janet Bull: I think of it as being able to go deep within to whatever those resources you’ve built up to be able to rely on. It’s having that well to draw from.

Eric Widera: Yeah.

Arif Kamal: Mm-hmm (affirmative). Yeah. I think about thriving in the face of challenge, recognizing that resiliency is not getting rid of all challenges that exist. Oftentimes when people think about, well, how do you create less burnout or higher resiliency? People oftentimes jump towards getting rid of the challenging things, like, “Oh, well let’s just do less call or less weekends, or let’s just get rid of the challenge.” It’s not that as so much as being better prepared to thrive in the midst of challenges. But some of them you can’t get rid of them. Now, some of them you can or improve.

Arif Kamal: The other way I think about that too, Bryan Sexton here at Duke talks a lot about this too, is this idea that burnout is the impaired ability to experience positive emotion when it’s there in front of you, so that when there’s true happiness happening, that you can’t see it. Conversely, resilience is the ability to see it when it’s there.

Arif Kamal: It’s interesting just from a human evolution perspective. If you were to ask most people like, “Right now, immediately, tell me a joke, a really funny joke,” most people pause. But if you ask them, “What does a rattlesnake sound like?” Most people can tell you what it sounds like even though most people have not seen a live rattlesnake actually rattle at them, but they’ve seen it or heard of it in some way where those negative sort of sounds are a lot easier to draw upon than the positive. That turns out true here too. When there’s an emotion and you can see it for what it is, is really what resiliency means. It’s seeing good for what it is when it’s there.

Alex Smith: (rattlesnake sound)

Eric Widera: Is that the rattlesnake, Alex?

Arif Kamal: Yeah!

Alex Smith: Glad somebody got that. That was my rattlesnake joke so you got twofer. Yeah.

Eric Widera: I’d love to talk a little bit of how common is it, especially when caring for seriously ill adults. We’re going to talk about the study that you guys did, but before we talk about that. Why did you even think about doing a study like this? How did you get interested in this concept of burnout? Arif, want to turn it to you.

Arif Kamal: Well, I think there was this… I mean, Janet’s been a close colleague and friend for a long time now. I think we had a conversation with a few others too about this idea. Maybe, as I remember, it was about a bit of equipoise in the field because there was this “Well, palliative care people are really good at yoga and mind-body and reflective practice.” So, obviously our prevalence is going to be lower, and then it was like, “Well, but this work is hard to do too,” so there was this camp of, “Well, maybe it’s going to be higher.” You also recognize that the rate in healthcare, for one, is high anyways, so it was trying to benchmark against what already exists. We thought what better than to actually check in with our colleagues, not only about the prevalence issue, but also the predictors issue and what are strategies people are using to help build resilience.

Janet Bull: Yeah. I think the other thing we were seeing is a workforce shortage issue. Everywhere I went, people were saying, “We don’t have enough people on our team. We’re getting killed by more consults than we can handle.” And so there was this kind of, “We love this work. This is really meaningful work, but it gets to the point that we’re a product of our own success.” Now everybody wants palliative care and it’s exploding throughout the system and what am I going to do? How am I going to take care of myself? We were really interested, how much of a problem is this in our field? Because people do come to palliative care and hospice work often because it is very meaningful work.

Eric Widera: Yeah. I’m just guessing that the prevalence is going to be a little bit high too, based on the fact that the making of meaning in our work, like when we actually sit down and take time with our patients, it’s very meaningful, impactful. But there’s a lot of fast food palliative care growing out of that give. If you have 20 new consults or 20 patients on your service that day, it’s hard to create meaning when you’re just seeing patient after patient and patient. I feel for those interns who are doing that even outside of palliative care. So what did you find? How common is it?

Arif Kamal: Well, here’s what’s interesting. What one finds when you do enough research is a level of humility that one cannot necessarily predict from the very beginning. So here’s what one finds… is we did this study with a very large survey and reported some numbers in the literature. And then we repeated that survey a couple years later for a different project we were doing for health affairs, and the numbers were very different. So, we thought, “Well, it can’t be that different in such a short period of time.” So we went back and realized, in fact, that we had made a mistake in the first study that we put out. We reran those numbers and found that in fact, the numbers that exist, the prevalence in the 2016 article, really should align with what we found in the 2019 article, which is around 45% or so.

Arif Kamal: Where we were tracking as a field was with really sort of the average across medicine. Now there’s two conclusions to that. One is, again, this real sense of humility around sort of “Yep. Investigators make mistakes,” and we made one and we corrected it and we published it again with the right numbers. But two, more importantly, is actually the message from that, which is that for those of us who thought that maybe it’s going to be low, it really wasn’t. It directly continued to correlate in both papers, even with the correction, with the risk of people leaving the field.

Arif Kamal: So, to Janet’s point, this idea that we have an insufficient workforce, high turnover, and that’s related to the burnout rate means that any rate above zero is more than where we want to be. And in particularly, for a young field like ours, where there is now more work than there are people to do it, that’s a real threat in a very different way than it is to oncologists or cardiologists or others who may have a burnout rate close to 45%, like what we have, but who do not have such a strong relationship with essentially the solvency of the field and the rate of itself.

Alex Smith: Yeah. I just would love to… can you clarify when you say “we and the field,” you’re talking about hospice and palliative medicine providers, doctors only, doctors, there’s practitioners, nurses-

Janet Bull: We had doctors and nurse practitioners in this study. What we found was that 47% were going to leave the field within 10 years. Well, that was in 2016. We’re we’re halfway there now. I think part of it is because there’s a lot of mid-career people like myself who came over from a different field. I think COVID has probably accelerated that as it has in all areas of medicine. But I think what it does is it leaves us with an inadequate workforce. So this is not a problem that’s going to be solved quickly.

Arif Kamal: Yeah. When you look at subpopulations there, you start to see higher rates among those providers who do mostly hospice or exclusively hospice. Among those that are non-physician clinicians, which is admittedly an awkward term, and since I haven’t found a better one for it, but that’s neither, that’s not a judgemental statement. That’s just sort of all the important members of the IDT team who don’t have an MD behind their name also bear the brunt of this for various reasons.

Arif Kamal: We followed that up with some focus group work to really identify what are the embedded challenges in that. It’s interesting, the things we heard. So for example, if you have a team where the backbone of it is, let’s say, an advanced practice provider who’s there 1.0, and you’ve got a 0.25 physician who rounds every now and then. What we heard is people saying, “Look, the people who are on this team every single day don’t necessarily have an outlet.” And we see that as being a predictor of people with burnout across any industry is job rotation and responsibility rotation, is that fundamentally as human beings, we like doing different things. But if a consult service needs someone there every single day doing that work, it’s really important work, but it can contribute without any embedded rotation in responsibilities to burnout.

Arif Kamal: We start to see that higher in advanced practice providers who are the part of the service and not necessarily as high in the physicians who get to come in and then leave and go do something else. You also think of other professional responsibilities like teaching or QI projects or going to meetings that may be more inherently part of what we allow physicians to do, but may not support the time or resources for other team members to do that as well. We heard that in the focus groups as there was really a real disparity in that issue. I think what we took from that was a call to action to try to equalize some of that so that our non-physician clinician colleagues do get opportunities to go to professional meetings, to do teaching, to do QI work, to be with the residents and the learners and do other things.

Eric Widera: Yeah. I think it’s a challenging thing. I’m just thinking about all the times I’ve been burnt out, including recently. Sometimes going back to the clinical work, I’m very privileged that I go off and I go on; I go off and I go on. But I’m juggling a lot of different things. Sometimes all of that juggling just makes it so when I come back on the clinical service, it’s really hard to really focus on the person that’s in front of me. I think for me, that adds to my own burnout out because it then becomes less meaningful. Sometimes actually not having all of those other things to juggle and really just focusing on the thing that’s in front of me, the patient, the family that’s in front of me, feels also like it’s protective for me. But I also understand, I also have the luxury of stopping. We do service for half a month at a time, and half a month I get focus on other things, which I also understand is very protective for me as well. Thoughts on that?

Janet Bull: I think it’s different for different people. Some people are more stressed out when they have to juggle lots of different requirements to a job. At Four Seasons, we have found that nurse practitioners who work in the hospital really want to stay in the hospital and not necessarily work in the outpatient arena and vice versa. Those who are comfortable in the nursing home, in the home setting, often may not be comfortable in the hospital setting. So, I think having some flexibility around what individual choice or preference is, is helpful. I think the other thing is really having a solid team where you’ve got built-in debrief, where you can tag-team so that if you’re having a bad day or one of your colleagues is, you can pitch for each other.

Eric Widera: Do you get a sense of is it all different between if you’re doing palliative care in the hospital and palliative care in clinic? Because what we’re also seeing a lot of, especially recently, is the amount of inbox management and feeling like you’re always on. You never have that break like you do as an inpatient in tending. Did you get, from the health affairs article, any information about outpatient versus inpatient or location of your clinical work?

Arif Kamal: Maybe not so much that, but what may be related to that is the sense of belonging to a team was an important protective factor. What’s interesting is that that’s not actually how many people are on the website whose pictures are around you. It’s really your sense of feeling belonging to a team. There’s plenty of lot of people sitting in a room, but they’re not working together as a team. There’s examples of that, obviously.

Arif Kamal: So I think here, I would argue actually the bigger issue is not maybe so much inpatient-outpatient. It’s really whether there is a supportive structure around you, in particular colleagues you can commiserate with, workload that you can share. When you have team members, then you have an ability to calibrate workload. You can enable some amount of flexibility, But if it’s one clinic with one clinician, there’s only so much flexibility one can have. What you end up doing, as Janet will point out, is those clinicians will just start walking in late and then later and later, and then things will start to suffer. But it’ll happen in a very pervasive kind of way, where if you have clinicians around, you can say, “Hey, I’m going to come in a little bit late because I’m going to drop off my kid to school because they have this recital thing,” and “Oh, okay, well, I’ll see that patient for you.” So you can start to build in flexibility. That’s what we started seeing in this study that I think it’s really more about the supportive piece around you than maybe the location.

Janet Bull: I think it’s really hard for people who are in rural settings. We saw this in our project, ECHO Project in this last couple of years, where nurse practitioners often are in isolated… They’re the team, and they may be in a rural area and they’re seeing all these consults and maybe they have the luxury of a social worker, but maybe they don’t. So, they don’t really get that relief that Arif is talking about. And that makes it really, really difficult.

Arif Kamal: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Eric Widera: And you know, if you haven’t heard in the last two years, there’s been a global pandemic going on. (sarcastically)

Eric Widera: What?

Eric Widera: Yeah. Yeah. I just heard about that in the news the other day.[laughter]

Alex Smith: Do you think the rates of burnout has changed at all?

Janet Bull: Yes.

Alex Smith: Yeah?

Janet Bull: Oh, yeah. Yeah, no. I mean, I think there are several studies out there in the general medicine population. The Kaiser Foundation put out a recent study in ’21 looking at the rate of burnout. What was really fascinating about this study, there was a overall, I think it was a 55% burnout rate, but it was highest in those healthcare providers who were between 18- and 29-years-old. It was 70% and 75% in that age category had… Some said it affected their mental health.

Alex Smith: Wow.

Janet Bull: That’s really, really huge.

Alex Smith: Yeah.

Arif Kamal: Yeah. I agree. I think that what people are doing, which is fair, is really critically looking at their workplace, their employer, their colleagues, and others, and just asking themselves… Probably, in a lot of ways you can judge character during times of crisis. I think there’s some judgment going on. I think if your institution sent out a bunch of, “We’re all in this together,” in the midst of the pandemic, but somehow those messages went away, that you might draw a particular conclusion about that.

Arif Kamal: I mean, I remember getting an email from the CEO of Reebok about we’re all in this together and I can tell you my initial response was one, I’m not sure when I last bought a pair of Reebok shoes. And two, are we though? Like, are we though? Are we? And I think, particularly for palliative care folks who are, I think, across the board, sincere, genuine, reflective people as a tribe as we are, there is some examination going on about that. I think maybe it’s been brought up, it naturally, if there’s a great resignation, I think some of that will absolutely touch palliative care as well and some re-exploration of what people want to do.

Arif Kamal: There’s some interesting literature that most employees will stay in the job that they’re in as long as they’re able to do the thing they love the most at least 20% of the time, which is an interesting reflection because it’s not saying 50% of the time, 75%, 100% percent of the time. So, what you have to ask yourself is that if you’ve got folks on your team that really love being educators and educating others, are you carving out at least 20% for let them to do that? And then they’ll do the rest of it for the 80% or so. I think that 80-20 rule here applies, and I think it’s really important for leaders and managers to think about is, do I understand essentially the 80-20 rule for all of the people that work on my team is do I know the 20%, the thing that they love doing the most, and how am I enabling them to be able to do that?

Eric Widera: Yeah. Yeah. I got to say, going back to the Reebok, my last pair of Reebok was when I was a kid. It was those little pump-up ones, you know, the-

Arif Kamal: Oh, yeah. Yeah.

Eric Widera: You pump them up.

Arif Kamal: Shaq, yeah, yeah.

Eric Widera: And-

Janet Bull: You had lights on yours, Eric.

Eric Widera: Yeah… As I talk to people from across the country, I do feel like we are hitting that hospice and palliative care and also geriatrics, great resignation, that people are reevaluating, rethinking what they want to do and where they want to do it, and if they want to do this at all, medicine at all. I wonder if we can turn to including like the 80-20 split, both individual and systems things that we can change to help build resilience and reduce burnout. So I hear one of them: at least get 20% of your time doing the things that you love. Other things that we can do from a systems perspective.

Janet Bull: Well, there are individual and organizational strategies. From a systems perspective, I think recognizing people for what they’re going through, having a place where they can vent, where they can debrief together, building that in as part of a core strategy. One of the things that our organization did this year was we made part of our health plan the telehealth for mental illness or for therapy sessions available to every employee and every member of their family for free. I think one of the things that we instituted on our research team, where we have Zoom meetings twice a week, since we’re not meeting in person, that you can take off your camera and you can go walk two miles while you’re on your Zoom session, or you can take your dog out. There’s no reason we need to be connected during videos. But trying to think of ways as an organization that you can support each other, whether it’s increasing flexibility and the work schedule, or just acknowledging people. There’s lots of ways you can acknowledge people for what they’re going through.

Arif Kamal: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Eric Widera: Do you think Zoom is helping or hurting with burnout? Because I also feel like Zoom does not do a very good job of connecting us to each other. Not like it used to be. I guess it’s better than nothing. But I’m starting to come to work pretty much every day of the week just so I can actually be with people and see people and be part of that team again. What do you think about that?

Janet Bull: I think there’s a combination of strategies. Telehealth, I think, will be here to stay, and I know we’ve had some really great telehealth sessions with our family physician, and I prefer that. I’d rather not go in the office personally, if I can get what I need on a quick chat on the phone. So I think it’s going to be a combination. In terms of meetings, I think being creative. Honestly, I have my headset on and I’m often paddle boarding when I’m on a meeting.

Alex Smith: That’s great.

Eric Widera: I remember, I think Janet, you were on one meeting, you were a biking around another country. I was on with you.

Janet Bull: Oh, yeah. I was.

Eric Widera: Arif, thoughts? Zoom team meetings.

Arif Kamal: Well, one, that Janet has a better sense of balance than I do, because I don’t know if either of you paddle board. But man, geez, I can’t stay on for very long… No, I think from a systems perspective, look. I think you should put your money where your mouth is. I see a lot of initiatives where people are sort of… Tait Shanafelt wrote a great thing in JAMA Internal Medicine back in 2017 about the business case for investing in physician wellbeing. In there, he published essentially a continuum of where organizations stand. The lowest level of organizational approaches is promoting mindfulness and individual practice across everybody. Like, “Hey, everybody, here’s a group on for 30 minutes of free mindfulness training,” or something like that. That, by the way, on the rung of… is the lowest rung of that ladder, okay?

Arif Kamal: Now, where do high-functioning organizations get to, is they say, “Look, we will hold our leaders accountable for this issue.” Meaning look, every health system has bonus structures around 30-day readmission rates where the CEO of the hospital does better when the readmission rate goes lower. And that’s fine, no judgment against that. But I would ask, how many organizations hold their leaders accountable at a financial level for the cultural wellbeing, the resilience levels, the burnout levels, et cetera, for their organization? I think until you do that, there’s a lot of just talking out of one side of the mouth. I would say put your money where your mouth is, and make it as equally important as the 30-day readmission metric for anything related to compensation or bonuses or that kind of thing. The high function organizations do exactly that.

Arif Kamal: Then what happens is it becomes a serious, serious thing. It doesn’t become sort of a side program like, “Hey, you could do this thing if you want.” And it really starts to trickle down to the rest of the organization and there’s just accountability. I think that accountability, frankly, can occur at the manager level too. So if you said, “Look, our unit, our division, our organization thinks this is really important,” and you go, “Great. So whose promotion, salary, what is on the line related to this topic?” And the answer to that is, “Oh, no, no. It’s just a nice thing for us to do.” Then you have your answer, right? You kind of know where the whole thing stands.

Eric Widera: Yeah. It’s hard too though from a managerial perspective is when the organization is tracking RVUs, number of clinic patients seen or inpatients seen and all these other factors, which may also go against overall wellness and burnout too, is that, thinking potentially is there some type of balancing factor. Again, using that Maslow inventory as a balancing factor from those other factors, which one do you prioritize? Ultimately, most organizations it’s about the RVUs, that income being brought in.

Arif Kamal: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Janet Bull: But we know the cost of people leaving an organization, right?

Eric Widera: Yeah.

Janet Bull: So I think you got to find that balance. There is a lot of data, as Arif mentioned, on reflective practices. And Tait showed that if you train physicians, even in mindfulness, that that impact 6 months, 12 months down the road still holds benefit. So-

Eric Widera: Let’s talk about that. Individual factors. What are we actually doing when we’re talking about mindfulness?

Janet Bull: Well, for me, I’ve been a meditator for probably 35 years. Getting a mindfulness practice to me is a time in the morning to quiet my thoughts, to get centered for the day. I think for some people it may relate to prayer, but there’s a lot of forms that meditation can take. It’s this kind of reflective practice that allows you, or it at least allows me to kind of center myself and to know how do I best take care of myself? How do I best take care of others? It’s a practice that people can learn. We know the science behind meditation. It decreases your interloop in six levels. It decreases cortisol levels. It increases your hippocampus, which is your empathy center. So there’s lots and lots of benefits to meditation that have really been shown in the literature.

Janet Bull: So having a reflective practice, I think is important. Having clarification of one’s own personal goals is also important, finding work that is meaningful and brings you passion, and then having an outlet, having physical activities, whether it’s a walk in nature or a bike ride. Getting yourself stimulated physically, and then finally having a gratitude practice has been shown, again, quite a bit of research has shown that gratitude… And as Arif was talking about, kind of this positive emotion…

Eric Widera: Can you give me an example of a gratitude practice?

Janet Bull: Yeah. I went to this course that Arif talked about with Bryan Sexton years ago, and they talked about this, writing three grateful things in a journal each day. I went back home and I said, “Gosh, that sounds like that’s going to tax me. I don’t know. That’s just going to add one more thing.” So I got four of my colleagues around the country and I said, “Hey, you guys, what do you think if we started a gratitude club?” Just we would write emails, maybe once a week, of the three best things that happened in our life. That was five years ago. To this day, those are my favorite emails. These are folks you probably all know pretty well. It’s not about the work. It’s about what’s going on in their personal lives. It’s our connecting together as human beings, sharing each other’s joy, hearing what happened to that other person that was so great, and then being able to share that. So that’s kind of a simple example.

Eric Widera: Thank you. Arif, other thoughts. Individual things that we can do?

Arif Kamal: Well, I’ll just… shameless plug here. So, during the pandemic the work I do is around app development. I was on a Zoom call with our app developers, a startup company here in the Triangle. And just this… Do you guys remember like early 2020, the look on people’s faces? Just this like despondency, like what has happened. This was in the midst of like, you didn’t know if there was going to be enough toilet paper in the world, let alone… So on Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, we were pretty low on that pyramid, to try to figure it out. So, there’s this look of despondency across our software engineers. They said, “We need to do something else,” and said, “Well, we should take this really good work about gratitude journaling and create an app.”

Arif Kamal: So we created a free one called The Three, the number three, goodthings.org, the number three, good things.org. It’s a free… It’s essentially what Janet just said. It’s a way to create a circle or a network and to share within that through an app, and then the app can send you a text reminder at a time point you designate every night, and it can remind you to write those three things.

Arif Kamal: To Janet’s point, what Bryan’s work has shown is that if you do that for as little as two weeks, there are benefits to depression and resiliency seen six months later. So the important part here is gratitude journaling, although Janet and her friends have done this for a long time, it can be done in small bites, meaning that you can do it for a couple weeks, put it aside and it still helps you for a while because it’s rewiring things in terms of how you think about things. When I’ve done this with friends and colleagues too, what people start to say are things like, “Oh, I’m just now more aware and cognizant of these things,” because really, fundamentally, their life wasn’t different during that two week period of journaling. That’s not what happened. They were just more aware of it.

Arif Kamal: I think in terms of other… This kind of dichotomy between organizational changes and individual changes… The AMA also has an 80-20 rule, which is that, and I think this is informed by Tait’s work as well and some others, is that really 80% of burnout is really an organizational issue and 20% is an individual. The point is it’s trying to shift the pendulum back towards this is an issue of you’re just not meditating enough, which may be part of it maybe, but there’s a lot of other things we can all think about-

Eric Widera: EHR.

Arif Kamal: -EMR.

Eric Widera: Yeah.

Arif Kamal: Yes! Right. Like… Right. We can all think about things that get in the way where it can feel like frankly, a bit disingenuous and a bit scapegoating if your health system says, “Look, here’s another group on for another Yoga thing,” which is fine. It’s great. But your EMR still stinks, and until those systemic issues are going to get fixed, or there’s at least organized efforts towards doing that, you’re not going to get rid of the things that are fundamentally going to be the rocks in people’s shoes, that even though you may change the shoes, you didn’t get rid of the rock. Even though you may polish the shoe, you didn’t get rid of the rock. Like, one of the days you just have to get rid of the rock. And that, for many people, is going to be things like pay and autonomy and work schedules and flexibility issue and EMRs and other things too.

Arif Kamal: I think fundamentally, really good leaders will ask people, “What is the rock in your shoe as it related to your emotional wellbeing at work.” What we’re trying to get at there is not why would you leave because if someone’s there, as Janet, I think, will tell you, if they’re there, it’s probably hard-pressed to keep them. If they see it as a rock in their shoe, then you’re at a stage early enough where you can name it and start to do something about it. It may be some of the things I just mentioned, but likely it will not be people saying, “Because I don’t do yoga enough.” I mean, you’d be hard pressed to find people saying that.

Eric Widera: Yeah, that’s always the challenge is also time is that when you’re working late after a busy day of consults, trying to find time for reflection, yoga, or any of those things, as you have to go back to the family, make dinner, do all these other things. It’s just, something’s going to give, and it’s usually those great self-care skills that we talked about but a lot of us don’t do, including myself…

Janet Bull: Yeah.

Eric Widera: Actually, I go on walks daily. That’s my self-care. Our entire family, we just go and walk every night. I love that.

Janet Bull: That’s great.

Eric Widera: That is… Yeah. That was my paddle boarding.

Janet Bull: I was going to say there was a psychologist named Herzberg that talked about the motivation hygiene theory. What motivates people in the workforce, what brings them satisfaction is things like being able to advance at work, having a growth plan, finding meaning in the work you do, being recognized for the work, having a sense of a responsibility. Then the things that he termed in the hygiene, which was like how much money I make, what the company policies are, the EMR. If you fix those things, if you paid people more, if you relax some of the policies people didn’t like, it actually didn’t bring satisfaction. It just lessened dissatisfaction. So, focusing… I think it’s really interesting. I mean, you know-

Eric Widera: Yeah, those were the motivators and demotivators, right?

Janet Bull: Right.

Eric Widera: There’s things that motivate you, like finding meaning and things that bring you job satisfaction. Then there’s demotivators. So the more money you make is not going to actually motivate you. What’s going to demotivate you fis eeling like you’re not getting paid fairly. That’s the problem with bonuses, right? You get a bonus one year. If you don’t get the big bonus the next year, it’s actually going to be a demotivator. You’re not actually going to be working harder because you got a bigger bonus. You’re now going to actually have less job satisfaction because you didn’t get that same bonus and you’re more likely to leave.

Arif Kamal: Hmm.

Janet Bull: I mean, I think the point is you want to focus on it. I mean, if you can correct some of the demotivators, certainly do that, but you really want to focus on the things that add to job satisfaction.

Eric Widera: All right, my last question for both of you. You have a magic wand. If you could change one thing right now, the magic wand is running out of batteries. You got one thing. What would you do around wellness, self-care, resiliency and burnout? Arif, I’m going to go to you first.

Arif Kamal: I’m going to cheat. Two parts: one, normalize it, normalize it, normalize it, normalize it, and in normalization of it reflect that resiliency is a skill like leadership and communication. It’s not an inherent trait. You are not good or bad at resiliency. It is just a skill you need to work on and you need people around you to work on it. Then lastly, if your leaders are not incentivized to improve it, then it is not an institutional priority. If your leaders are not incentivized to improve it or held accountable to it, it is not an institutional priority,

Eric Widera: But they’re sending me emails. Isn’t that enough, Arif?

Arif Kamal: Yeah. Reebok sends me emails too, but I don’t buy their shoes.

Eric Widera: Janet. Magic wand.

Janet Bull: Yeah. So I think the first is to take an inventory of where you are as a provider. Where do you fall on that scale? What’s your level of burnout? Are you neglecting your own needs? And if you are, take a minute to pause and give yourself space. I talk about… Martha Twaddle and I wrote a talk on Don’t Be a Boiling Frog. It talks about what happens to people as they accommodate to job pressures and stressors. As the water starts to heat up, they lose that ability and they slowly cook, like a frog slowly cooks, to that. So really kind of take inventory and jump out. It’s irresponsible not to be happy, and you have to be responsible for your own happiness. I don’t know if I answered your question, in that magic wand, but it’s really kind of about taking inventory and change the things you can. If your organization doesn’t change, maybe it’s time to change your organization, honestly, if you can’t live in that environment.

Eric Widera: Great. Well, I want to thank both of you, but before we end this, maybe we can get a little bit more of that song.

Alex Smith: A little bit more Scotty McCreery. Here we go…

Eric Widera: Alex is going to do this one-handed-

Alex Smith: Yeah, one-handed.

Eric Widera: -since he has a clavicle fracture.

Janet Bull: I want to know how you broke your clavicle.

Alex Smith: I was doing my practice of biking, which is my release activity, but unfortunately it was going downhill way too fast, trying to do a virtual race on my gravel bike and slid around a corner and slammed into the ground.

Alex Smith: All right. Let’s try. This is from the beginning. Here we go.

Alex Smith: (singing).

Janet Bull: Nice job.

Eric Widera: Arif, Janet. Big thank you for joining us on the podcast!

Janet Bull: Thank you for having us.

Arif Kamal: Thanks for having us. That’s a great song.

Eric Widera: And thank you Archstone Foundation for your continued support and to all of our listeners, thank you for joining us on the GeriPal podcast. Have a good day, everybody.

Arif Kamal: Stay resilient.