Ambivalence is a tough concept when it comes to decision-making. On the one hand, when people have ambivalence but haven’t explored why they are ambivalent, they are prone to bad, value-incongruent decisions. On the other hand, acknowledging and exploring ambivalence may lead to better, more ethical, and less biased decisions.

On today’s podcast, Joshua Briscoe, Bryanna Moore, Jennifer Blumenthal-Barby, and Olubukunola Dwyer discuss the challenges of ambivalence and ways to address them. This podcast was initially sparked by Josh’s “Note From a Family Meeting” Substack post titled “Ambivalence in Clinical Decision-Making,” which discussed Bryanna’s and Jenny’s 2022 article titled “Two Minds, One Patient: Clearing up Confusion About Ambivalence.”

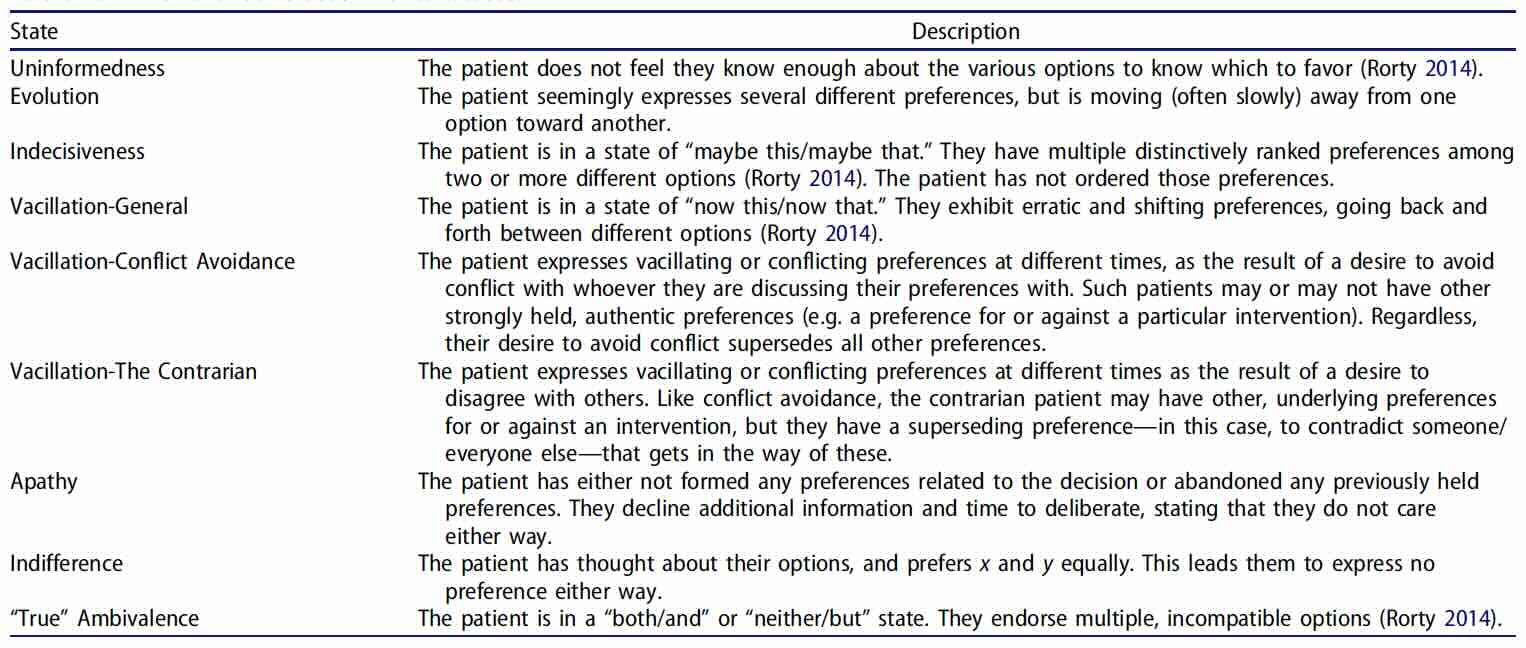

Bryanna’s and Jenny’s article is particularly unique as it discusses these “ambivalent-related phenomena” and that these different kinds of “ambivalence” may call for different approaches with patients, surrogates (and health care providers):

In addition to defining these “ambivalent related phenomena” we ask our guests to cover some of these topics:

- Is ambivalence good, bad, or just a normal part of decision-making?

- Does being ambivalent mean you don’t care about the decision?

- What should we be more worried about in decision-making, ambivalence or the lack thereof?

- The concern about resolving ambivalence too quickly, as it might rush past important work that needs to be done to make a good decision.

- What about ambivalence on the part of the provider? How should we think about that?

- How do you resolve ambivalence?

Lastly, the one takeaway point from this podcast is that the next time I see ambiguity (or have it myself), I should ask the following question: “I see you are struggling with this decision. Tell me how you are feeling about it.”

***** Claim your CME credit for this episode! *****

Claim your CME credit for EP306 “Ambivalence in Decision-Making”

https://ww2.highmarksce.com/ucsf/index.cfm?do=ip.claimCreditApp&eventID=12509

Note:

If you have not already registered for the annual CME subscription (cost is $100 for a year’s worth of CME podcasts), you can register here https://cme-reg.configio.com/pd/3315?code=6PhHcL752r

For more info on the CME credit, go to https://geripal.org/cme/

Disclosures:

Moderators Drs. Widera and Smith have no relationships to disclose. Guests Joshua Briscoe, Bryanna Moore, Jennifer Blumenthal-Barby & Olubukunola Dwyer have no relationships to disclose.

Accreditation

In support of improving patient care, UCSF Office of CME is jointly accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME), the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE), and the American Nurses Credentialing Center (ANCC), to provide continuing education for the healthcare team.

Designation

University of California, San Francisco, designates this enduring material for a maximum of 0.75 AMA PRA Category 1 credit(s)™. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

MOC

Successful completion of this CME activity, which includes participation in the evaluation component, enables the participant to earn up to 0.75 MOC points per podcast in the American Board of Internal Medicine’s (ABIM) Maintenance of Certification (MOC) program. It is the CME activity provider’s responsibility to submit participant completion information to ACCME for the purpose of granting ABIM MOC credit.

ABIM MOC credit will be offered to subscribers in November, 2024. Subscribers will claim MOC credit by completing an evaluation with self-reflection questions. For any MOC questions, please email moc@ucsf.edu.

Eric: Welcome to the GeriPal podcast. This is Eric Widera.

Alex: This is Alex Smith.

Eric: And Alex, we’ve got a lot of ground to cover Today. We’re going to be talking about ambivalence with four amazing guests. Who is with us today?

Alex: We are delighted to welcome Bryanna Moore, who is a philosopher and bioethicist, and she’s at the University of Texas Medical Branch where she also directs the clinical Ethics Fellowship. Welcome to the GeriPal podcast.

And we’re delighted to welcome Jenny back to the GeriPal podcast, Jenny Blumenthal-Barby, who’s a philosopher and bioethicist and associate director for the Center for Medical Ethics and Health policy at the Baylor College of Medicine. Jenny was previously on our podcast talking about the ethics of nudging. I know Eric’s mentioned that podcast maybe in every podcast since-

Eric: Pretty much every podcast since then. Been nudging people to listen to the podcast.

Alex: That’s right. Jenny, welcome back to GeriPal.

Jenny: Good to be here.

Alex: And we’re delighted to welcome O. Mary Dwyer, who is a lawyer, and bioethicist and assistant professor at Case Western Reserve and University Hospitals. O. Mary, welcome to GeriPal.

O. Mary: Thanks for having me.

Alex: And we’re delighted to welcome back Josh Briscoe, who we last had on talking about the Uncanny Valley, something we mentioned on the podcast we recorded yesterday with Bob Wachter. He is a palliative care physician at the Durham VA Medical Center in Duke and blogs on Substack at Notes from a Family Meeting. Josh, welcome back to GeriPal.

Josh: Thank you, you all.

Eric: So yeah, we got a powerhouse of guests. Today we’re going to be talking about ambivalence, what it is, what should we do about it. It’s all stemmed from a post that Josh wrote, I’ll caught from his Substack Notes from a Family Meeting. We’ll have a link to that on our show notes, so a lot to ground cover. But before we do, we always turn to a song request. Jenny, I think you have the song request today. Is that right?

Jenny: I do. Alex, I’m going to request Peace of Mind by Boston.

Eric: Why Peace of Mind Jenny?

Jenny: I mean I feel like it speaks for itself. It’s a song about understanding about indecision, but wanting peace of mind. So I thought it was perfect for a podcast on ambivalence.

Alex: Great choice. Now I don’t have the full band and my hand’s still recovering from being broken, so I’m playing this kind of Jack Johnson style. So see if that comes through.

(singing)

Eric: On a scale of one to 10 for songs that perfectly align with topic. Jenny, I think you got a 10 on that one.

Jenny: That was great, Alex.

Alex: Great choice. Thank you.

Eric: So again, this for me this time from reading Josh’s Notes on a Family Meeting post or Substack post that came from, Josh, is that right? From you reading the 2022 article that was authored? I think the lead was Bry on that. Is that right Josh?

Josh: Yeah. Yeah. This was a paradigm shifting paper for me. Really helpful paper.

Eric: Before we go into the paper, because we’re going to talk about the paper. Why was it paradigm shifting for you?

Josh: Yeah, I think this is a big part of my work as a palliative care doc is helping people make decisions and 99% of the time they’re not ready to make a decision as soon as you lay out all the facts. There’s something that gets in the way. And we can talk some about how clinicians help or hinder that process in a bit. But yeah, it’s just something that stuck in my craw and they’ve just put words to everything I’ve been struggling with as a clinician

Eric: And I absolutely adore your post. I saw the first comment was Susan Block, who is, for those who don’t know, Susan Block is, we actually had our own podcast, one of the true leaders of our field.

I want to then turn to Bry then. Bry, before we talk about what you did in the paper, let’s take a step back. Why did you decide to write this paper?

Bry: Yeah, Eric. It’s funny. We started writing this paper in 2019 actually. I was a clinical ethics fellow at Baylor College of Medicine. Jenny was one of my mentors, remains one of my mentors. But my co-fellow and I, we were on service for the ethics service and we had a run of consults where the clinician who placed the consults framed the consult as an issue of ambivalence. So this, I think we had three or four consults. It was just one of those freak moments where sometimes you’re on service and there’s almost like there’s a theme to the week was ambivalence.

And so we had this run of consults and we walked out of each consult thinking and talking about how different each patient’s experience was. They were all struggling from really different places with very different things. So we felt like, hang on a second, there’s something really interesting to unpack here. And the source of their, “ambivalence,” because they were all just so different, such different flavors of ambivalence.

And so my co-fellow and I, both philosophers with one of our mentors who was our faculty that was working with us at that time, all trained philosophy. So we’re like, all right, we have some neat conceptual distinctions to be made here. So we really wanted to start to tease those out. And Jenny was not faculty in the clinical ethics fellowship, but we knew of her love for Harry Frankfurt and her prior work on Frankfurt stuff around ambivalence. And so we’ve reached out to Jenny to see if she might be willing to help us flesh out some of our thinking about this and these different case variations of “ambivalence.”

Yeah, so that was it. We just directly walked out of the hospital and we were like, we’ve got to write about ambivalence, what is going on here? And then the paper, we had some wonderful mentorship and it took shape from there.

Eric: Great. And Jenny, any ambivalence in writing that paper?

Jenny: No ambivalence in writing that paper. But I wrote my dissertation on the topic of ambivalence, and so it was for me, this thing that I was trained in philosophy was in grad school and encountered a clinical case during an internship that I did at the Cleveland clinic. That was really a difficult case and I didn’t know how to think about it. And I remember somebody, I described the case to them and they said, “Oh, you’re interested in the topic of ambivalence.” And so I had a name that described what I was interested in and it just for me opened up this whole set of, I think really deep philosophical issues about respect for autonomy and how to conceptualize autonomy in cases of ambivalence. And so I did a dissertation on it and then just kind of followed it away wherever dissertations go. And then this opportunity with Bry and Ryan and Peter Ubel was an opportunity to revisit the issue and also make it more concrete in terms of some real clinical cases. So it was a lot of fun.

Eric: How about for you, O. Mary? How about where did your interests for ambivalence stem from?

O. Mary: So not unusual for most clinical ethicists. I had a case that was really distressing for a number of the team members involved. And I think that for that case in particular for the intensivist, it was clear that his reaction to that case unfortunately led to him being ambivalent that he literally said to me at one point, deadpan shrugged his shoulders and said, “What do you want me to do?” And I was like, oh my God, this is a phenomenon that I don’t feel like we fully flesh out or recognize when it happens. So that’s my answer.

Eric: So not from the patient perspective or family, but from the provider perspective?

O. Mary: Yes, very much so. Yeah.

Eric: All right, let’s jump to the beginning again. What is ambivalence? Jenny, I’m going to turn to you since you got a dissertation on this. If you go back to your dissertation, if you could remember that far, how should I define an ambivalence?

Jenny: Yeah. I mean, it is a tough question actually as it turns out. I think the way I colloquially think about ambivalence is when somebody is making a decision about something and they’ve got mixed feelings about it or they’re indecisive, they can’t make up their mind, or maybe they make up their mind, but they still have feelings that are mixed about the direction that they went in. I would say for me, that’s just how we think about ambivalence colloquially.

In the philosophy world, Bry mentioned one of the philosophers that has done the most work on ambivalence is a philosopher Harry Frankfurt who passed away a couple of years ago. And for him, ambivalence is a phenomenon of the will. It’s that we as people, we exercise our will through making decisions and making commitments. And when we’re ambivalent, we just can’t make a commitment to one thing or maybe we make a decision or we make a commitment, but we’re not wholehearted about it, we’re not fully on board with it. So that’s the way that he conceptualized ambivalence.

Eric: Yeah, it’s interesting because when you think about the word ambivalence, you can have bivalent things, pluses or minuses, valence itself, isn’t that your emotional, it’s the positive or negative terms you attach to emotions, I guess ambivalence, multiple valences. How do other people on the podcast think about this? Josh?

Josh: In my clinical work, this comes up a lot when I see patients and they’re conflicted either in their goals, so they want multiple competing goals that can’t be reconciled. They want to live, but they don’t want to lose their gangrenous leg or they want to be at home, but they also want all the affordances of being in the hospital. They want to have their cake and eat it too. And so certainly competing goals can cause that competing priorities. I prioritize my relationship with my wife and what she thinks about what I should do with my health, but I also prioritize my own goals for my health and how do I reconcile those so other people can induce ambivalence and then just roiling emotions that they can make people conflicted.

I mean, hearkening back to the Uncanny Valley, we would like it if people were machines and we just gave them information and they spat out a response. But emotions are critical to the decision-making process, and they can really induce a great deal of ambivalence. And I think clinicians set people up to be ambivalent as well. The way they structure their choices, the patient’s choices, sometimes they give too much information, forms of toxic knowledge that just patients don’t need to know and that induces ambivalence. Or clinicians can seek to resolve ambivalence too quickly. Ambivalence should be a flag that something’s going on here, something’s important and we should slow down and pay attention to that. So there’s all sorts of interesting features to this landscape around ambivalence, and I don’t think we pay enough attention to it to describe it. So this is why I love this paper is it gives some handles on a really elusive concept that I think we need to pay more attention to.

O. Mary: And I want to piggyback on that, Josh, because you make some great points both for when it occurs in patients and also when it occurs in providers. Sometimes as clinical offices we get called in when patients, let’s say they shut down due to their ambivalence. They’re like, I’m tired of having this conversation. I can’t make a decision, so just leave me alone. And they don’t want to talk to anyone. And then it’s like, oh, they get labeled as a difficult patient. And then we have providers. The other way it manifests for them sometimes is that they’ve given so much information that we hope helps help a patient make a decision, but then at some point they get so frustrated with, oh, I’ve given them so much information, they should have been able to make a choice by now that they also then get shut down and say, well, I’m not giving them any information anymore. I don’t want to be engaged in this conversation. Leave me alone. I don’t want to go talk with them. So it happens. I feel like there are similar features of how it presents for both patients and providers when they’re dealing with this issue and that they can’t even put a label on too.

Eric: So let me ask you that question. Is ambivalence necessarily bad? Because the opposite of ambivalence may be you just make a quick rushed decision. It seems like ambivalence probably should be the starting point in most complex decisions because now you’re weighing your values, your identities, people’s other values and goals with potential paths moving forward. And should we be more concerned about when people are not ambivalent at the start of these complex decisions and they just go straight ahead? Is ambivalence always bad?

Josh: I would say no. And I think that that is a big part of what motivated our paper also was what we sometimes felt like we were hearing from the clinical team was like, why can’t this person just make their mind up? But we would go and talk to them and come out of the conversation like it is so reasonable that they are struggling to process and work through this really challenging decision that maybe there’s no good options. Maybe there’s just a fundamental conflict and things of importance to someone. They are really sitting with their options and sitting in that tension. And that for us, felt like almost like a good thing. Look how seriously someone’s taking this decision, right? They really want to make sure they get it right and that it’s a choice they can live with. So we wanted to unpack that a little bit in their paper and exactly as O. Mary said, push back a little bit. I think on the assumptions that we make that, well, this patient lacks decision-making capacity because they’re experiencing ambivalence or some ambivalence-related mental state or this patient’s just difficult. They won’t make their mind up or they can’t make their mind up. This is a difficult patient to work with. We wanted to push back against that a little bit.

Eric: And I can actually hear O. Mary’s story too of the provider. There are probably some places where ambivalence is good, especially when you know you’re ambivalent because then you’re processing through it. But people who feel ambivalent but don’t know, that’s probably a very bad place to be because really prone to really making some potentially bad decisions or indecisions, you’re using all those other biased assumptions, you get sidetracked. What do you think O. Mary?

O. Mary: Or you deprive them of a good recommendation that should be coming from your provider. That’s how I tend to see it, is that when they, it’s like you’re supposed to be the person who’s looking out for their best interests as their provider. Part of your role is to help guide them, not overwhelm them and say that you have to follow what I’m saying. But I think at the end of the day, at some point you should be giving them some guidance, giving them some recommendation. But if you’re ambivalent about whichever way they should go, I think you actually may be depriving them of information, important information they can use to help the patients make their own decisions. And without that, then you get stuck with ambivalence on both sides.

Eric: In some ways, in that case mean the provider then becomes your patient where you’re trying to help them think through their ambivalence because we’re probably not identifying that they’re ambivalent.

O. Mary: And I found that’s an area that’s lacking honestly for clinical ethics education of how do you respond when situations like that come up.

Eric: Yeah. Alex, you were going to say something?

Alex: I was just going to say there’s just so many things to unpack here and so many case examples come to mind. And just briefly, we had, Eric knows we had a very challenging ethics consult over the last few months. We had a seriously ill surrogate who lost capacity, who assigned two people to be his surrogate decision makers and wanted them to split decision making 50-50. Though they disagreed completely. And one of them felt certain in her perspective and the other person felt like she didn’t feel he was getting the care, that type of care that he would want at this stage in his life and was ambivalent because she knew that he wanted the perspective of the other surrogate to have weight. And that made us respect her perspective all the more because it showed that that ambivalent showed that care and that thought and concern and weighing these competing concerns.

The other story I tell is more along the lines of what O. Mary’s been talking about, the ambivalence of providers. I don’t know if you all saw, but there was a beautiful essay today in JAMA Internal Medicine by Randy Curtis’s wife and daughter about his end-of-life experiences. Randy Curtis we had on the podcast several times, he had ALS and ultimately used medical aid and dying to end his life. And they talk about how hard this was for them and yet how important it was for him to make that decision at that time in his life.

And there’s this beautiful essay by Ken Kavinsky that accompanies it, an editorial note where he talks about his opposition to medical aid and dying and how this essay nonetheless just pulls at his heartstrings and you can’t help but respond to it with compassion and empathy and how it’s moved him to a state of ambivalence around that very important issue. So those are just two examples that come to mind quickly where this ambivalence is just such an important area that requires this unpacking and distinguishing from that. There are so many layers to ambivalence, different meanings to ambivalence, and it’s also important to distinguish it from ambiguity, from uncertainty.

Eric: And I also love that ambivalence doesn’t mean you don’t care. It means that you have different feelings about something that you’re torn about something. And it just reminds me of Josh’s Post where he describes it’s like a warning flag. I’m going to paraphrase what you wrote, Josh. Anyone who hasn’t read Notes from a Family Reunion, you should. It’s beautifully written. I wish I can write as well as Josh.

Josh: Thank you.

Eric: But it tells us that there’s a major conflict, that there’s a conflict of emotions, goals, and if you try to resolve it too quickly, you’re going to rush past the important things, the things that need to be done to get a good decision. Did I summarize that correctly, Josh?

Josh: Yeah. And I think it also demonstrates how inadequate it is to just talk about mere preference satisfaction, to walk up to somebody and say, “Hey, what do you want? You want the surgery or no surgery? You want chemo or no chemo?” To ask what do you want is also to structure the choice in a certain way that pulls sometimes for fantasy. I mean in some situations it doesn’t matter what they want, what they is impossible.

Eric: I want to win the lottery.

Josh: Yeah. And so we set people up then to just go down a path and when we burn ourselves out, we waste time, we waste emotion, we set them up for ambivalence. That is almost a falsely constructed ambivalence. I think there are good forms of ambivalence. You’re wrestling with these big values you’ve been talking about, and then there’s ambivalence about, well, it turns out you really didn’t have a choice anyway, the clinician set it up the wrong way. And so I think this should make us all the more vigilant about how we ask people about their goals and values, and probably not starting with what do you want?

Eric: Yeah.

Jenny: I think this is a good. This reminds me of one of the categories we talk about in the paper is this category of, I think we call it uninformedness or something, but it’s basically where somebody can’t, they’re not making a choice or a decision because they’re missing a piece of information. And once you give them that critical piece of information, then all of a sudden actually they’ve made a choice. So if we just tag them as ambivalent and then this spirals into the negative responses that some of my fellow podcast guests have been talking about, then we missed in that case a pretty simple fix, which is that there’s critical information about their prognosis or about the experience. What’s it going to be like to have an LVAD or something like that that we could actually address?

Josh: I will say-

Eric: I love this. Go ahead Josh.

Josh: I will say on the flip side, I mean probably eight times out of 10 when I’m talking to a team that’s filling a new consult and I’m trying to get a sense and they say, well, the family just doesn’t get it. We’re in there every day talking to them about how bad this guy’s kidneys are. And they don’t need more information, but they assume the problem is being uninformed and they keep hitting them with more and more information and they’re in one of the other states that’s listed in the paper that frustrates them and annoys them and breaks down rapport.

Eric: Well, let’s talk about the ambivalent related phenomenon. Bry. I think this is the important part is everything that we know in palliative care and in ethics is curiosity is king here is to assume that you don’t, and specifically patients, doctors, healthcare providers, family members often don’t know why they’re experiencing ambivalence. They have difficulty correctly identifying the root causes or even their feelings about ambivalence. And I love this because it gives us some words for some distinct ambivalent related phenomenon that may be the root cause is about why they’re ambivalent. Is that the way I should be thinking about this, by the way, Bry?

Bry: Yeah, absolutely. That’s exactly kind of how we frame it in the paper. And I think for us it felt like such a helpful framing and I think I’m hearing for others it was helpful as well.

Eric: Yeah, what did Josh say was paradigm changing? That’s pretty big.

Bry: I don’t think anyone ever has or probably ever will say that about any of my work ever again. Much judge.

Jenny: Come on Bry.

Josh: I mean it’s a fantastic paper. People need to read it. It’s got to be in every palliative care fellowship curriculum. It’s got to be.

Eric: All right, let’s talk about ambivalent related phenomena. Can we quickly go through what are these ambivalent related phenomenon? We mentioned one, uninformedness. What’s that?

Bry: A super clunky name. Our apologies for that.

Eric: I have difficulty pronouncing it.

Bry: I should say too. So we built part of this taxonomy around an existing taxonomy by Amélie Rorty, who’s another philosopher. So Amélie Rorty had four states in her existing taxonomy, we felt like there were more distinctions and nuances to draw out. So we drew upon some of her categories and built out our taxonomy a little further.

This is what Amélie Rorty would call uncertainty. We felt like uncertainty was present in some of the other states too, so we tried to give it a different name. But this is exactly as Jenny said before where a patient doesn’t know enough about their various options to know which one to favor. So they need more information so that they can make a decision. So they appear to be experiencing some sort of ambivalence or inability to make a choice. Based on the fact that they just don’t know everything they need to make that choice. And sometimes that information is available and we can get it to them. Sometimes they want to know things that perhaps we don’t have answers to.

Eric: I love this one because it often reminds me too about sometimes we talk about illness understanding, we talk about the goals and values and we come up with a plan, but we’ve never talked about prognosis. Oh, by the way, you have days or weeks left to live, which is huge. I would probably not be on this podcast if I had days or weeks live. I’d make different decisions. The fact that people may be uninformed about that really important piece of information and how often that we don’t talk about prognosis, that for me reminded me about this for uninformedness. Okay.

Bry: Do you want me to jump through?

Eric: Yeah, I was going to say jump through.

Bry: We felt like this was really different to these sorts of situations where we felt like someone’s preferences were evolving over time or changing over time. They had started with a sense of who they were and what they wanted and then based on information that they were receiving, that was shifting. And it wasn’t that it was going back and forth, say between two options or two preferences, but that it was just this slowly unfolding, shifting and who they were and what they wanted. So we call that evolution.

Eric: It’s also highlights the need for sometimes time for ambivalence, need a little bit of time to think things through.

Bry: Yeah. And we wanted to try and be as value neutral as possible. You could be evolving towards good or some kind of new understanding of yourself, or you could be moving in a direction where it’s getting muddier and less clear about who you are and what you want. But we felt, again, that was different to a state of what we call indecisiveness. So this is where someone’s like, well, maybe I want this, I want that. I have several different preferences or things that are important to me and there’s two or more different options and I’m ranking them differently. And I don’t know which way I want to go at the moment. I’m indecisive. I haven’t ordered my preferences so that I can choose one way or the other. And we felt like that was different to having those preferences ordered and moving back and forth between different choices. We call that vacillation. So sometimes I’m sure you’ve all had experiences like this. The clinical care team will go in and talk to a patient and it’ll be like, yep, I want the surgery. I’ve thought about it. I am on board. Let’s go ahead and do it. And then you talk to them the next day and they’re like, “I don’t want the surgery.”

Eric: It’s usually when the attending walks into the room and it’s a completely different conversation. The intern says, “What the hell?”

Bry: “I was just in here talking to this [inaudible 00:27:54].”

Eric: That’s not what they said.

Bry: Yeah. But kind of day one, they’ll choose one thing, day two, another, and they’ll go back and forth between two options. You’ll get this vacillation that can be super confusing for everyone. I thought he was sure about this and now he’s not. And what if we act upon a certain day and then he experiences regret and it’s not really what he wanted and how do we know that he really has made up his mind if he’s changing it so often?

O. Mary: And that’s when we question capacity. That’s when often capacity is like, are you sure that person has capacity? Maybe we should be assessing that right now.

Bry: Yeah, they’re not communicating a consistent choice. It’s clear at a certain time point, but it’s not consistent over time.

O. Mary: Yep.

Eric: And there’s two other types of vacillation, right?

Bry: Yeah. We felt like sometimes, and I should say too, we wanted to be careful not to pathologize different mental states as well. That’s not at all our intention in this paper or my place as a non-physician, as a non-psychiatrist or anything like that. But we felt like sometimes people would vacillate in this way because they wanted to avoid conflict. So someone’s in the room and they want to say, “I don’t want to get into this person, so I’m just going to tell them what they want to hear to get them out of the room.” And then on the next day they can be like, oh, this person I know they want me to go ahead with the surgery, so I’m going to say, yeah, I’m good with the surgery. I thought about it. So sometimes it was this vacillation based on wanting to avoid certain dynamics or interactions with certain people.

And this was a little different to us from what we call the contrarian, which the patients who we feel like sometimes just want to disagree with people. So they’re going to do the opposite. They’re going to tell someone different things on different days to get different reactions from folks. And that can be for a host of really understandable reasons where they may have just very little control over their situation and it may manifest as them saying one thing to one person another on the other day. The only thing they have, right? Is to kind of contradict themselves and kind of say different things to different people.

And I think with vacillation it’s important to note someone might have ordered some of their preferences or what’s important to them, but they have an overriding preference to sort avoid conflict or to contradict people. That’s what’s driving them at that particular moment.

And I think O. Mary talked a little bit, particularly on the provider side about apathy where you just don’t care either way and you haven’t really thought about it, you’re just disengaged and apathetic. We felt that was a little different to indifference where you have thought about it and you kind of think, well, I prefer X and Y equally. I don’t really have a strong preference either way. I’ve thought about it doesn’t make much difference to me. It’s different to apathy where you’re not really engaged at all and you’re just completely kind of closed off.

And then true ambivalence. So Eric, you asked at the start of the podcast, what is ambivalence, right? I think we use it to describe all of these states, but what Amélie Rorty and what we call true ambivalence in the paper is when you want, Josh mentioned this earlier, multiple incompatible things at once. You thought about it, you’ve reflected on your preferences and what’s important to you, and you endorse incompatible options or incompatible preferences. You want both at the same time and you can’t have them both.

Eric: Well, first of all, I just want to acknowledge that at around 3:00 PM every day I think about what I’m going to have for dinner. I usually talk with my wife about it, and I’ve had each one of these ambivalent related phenomenon as I think about dinner. Including if my mood is bad, I will go to contrarian vacillation. Sometimes it’s just pure apathy. Sometimes it’s indifference or indecisiveness. So from a face validity perspective, this very much rings true. Now, the one thing I question though, is there such a thing as true ambivalence? Because all of these also just sound like not just ambivalent related phenomenon, but the process of ambivalence. These are all things that the normal process of ambivalence as we think about things, there’s a lot of things, the reasons that we are ambivalent and how much of this is just the reasons we are ambivalent or the process of ambivalence including evolution.

Jenny, I’m going to turn to you going back to your dissertation.

Jenny: Yeah, I think that that is right. Again, colloquially, just in terms of language wanting capture, when we talk about this phenomenon of ambivalence, I think one way to think about it is that these are all manifestations or mechanisms or ways that lead somebody to be ambivalent or indecisive about a particular decision. I think what true ambivalence is meaning to capture is this the really, really challenging case where somebody does have all the information and they’ve thought about it and they’ve done the hard work of digging into their values, and it’s just this really fundamental core conflict of incompatible values or incompatible parts of their identity that it’s going to be really hard to get a resolution around. I mean, some of these other related states you can imagine kind of paths forward, the contrarian, well, what’s triggering them, being contrarian, that sort of thing. So I think that I’m with you. I don’t know if we need to necessarily have this as a separate category, but I do think it meant to capture these really fundamental, tough, tough cases.

Eric: So when the person’s actually thought through their feelings and goals and values, and we’re in this really hard place because there is strong, not contradictions, but what’s the word I’m looking for? Conflicts. Let’s use that one. Josh, what are your thoughts on that?

Josh: Yeah, so I think it is, so the idea of ambivalence is really helpful both from a clinician standpoint because we need to flag what’s going on in somebody’s mental state. Like I gave you a choice A or B, and you can’t decide what is going on. And it’s going to matter a lot whether I’d say, oh, you’re delirious, or you don’t have the capacity to make this decision, or you’re doing it just to rile people up, or you’re doing it to satisfy your wife, or you need more information. It’s also helpful for me to know you have two big values that are in fundamental conflict with one another, and let’s talk about that.

And I think true ambivalence is a precarious state because I think two bad outcomes can result. One is, the patient either implicitly or explicitly takes as a goal of just resolving the ambivalence. It’s a very uncomfortable state to be in. And so they’re just going to make a decision just to get out of that uncomfortable state. And that might result in a bad decision. And the clinicians too. As O. Mary was saying, this doesn’t feel good for us either, so we want to get out of that state too. So okay, we’re all aligned and trying to get out of this ambivalent state as quickly as possible. Let’s just decide, and it doesn’t really matter.

Eric: Throw your hands up in the air.

Josh: Yeah. So that’s one danger. The other danger is just stalling out entirely. People are in the hospital for weeks and weeks languishing, and everybody just spins their wheels because nobody’s actually recognizing the value conflict and trying to work through that. And it’s an existential task. I mean, it is not straightforward work, and it’s not necessarily just tell me what you want. Like I said before, it’s like nobody’s sitting around on their couch Saturday nights thinking about their conflicting values. This is usually done ad hoc in the moment in crisis when you’re not your best. And so people are going to need support in doing that, but you need to know, I mean, you need the handles in order to recognize what’s going on.

Bry: Josh, I have no idea what you’re talking about. I sit at home every Saturday night reflecting on my values. [laughter]

Eric: I’m going to call you up when I have to make dinner decisions at three P.M. today.

Alex: I was just thinking about, Josh, do you have training in psychiatry?

Josh: I do. Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Alex: So think about this concept called reaction formation. I think from psychiatry where I learned this from Susan Block, when patients put you in a situation that reflects the struggle that they’re dealing with, and so in the case of ambivalence, if patients often feel stuck between X and Y, and they will transfer that feeling to physicians, they don’t know how to resolve it themselves. And so when you are as a clinician or as a bioethics consultant, you’re seeing a patient and you feel like I’m being put in a situation where I have to make a choice between two impossible alternatives and they’re incompatible. Something that you might consider is that this is coming from the patient and this is where the patient is at. And it’s like a signpost internally to you that, huh, the patient is struggling with this. I need to help them work through this because they’re putting me in this situation because they don’t know how to handle it. Is that fair, Josh? Am I anywhere close? No?

Josh: Yeah, If I could push back a little bit, and I’d be interested to get the ethicist perspective on this.

Eric: You push back a lot.

Josh: Because I feel like you’re in it. In a sense, this is the patient’s decision. In another sense, this is our decision together. And because clinicians are responsible for I creating this choice, I mean laying out the information, presenting it in a certain way, navigating this conversation. And so in a very real sense, this is our decision that we’re making together. And of course, the patient authorizes it or their surrogate authorizes the final decision, but the way it’s constructed and presented, it belongs to the clinician. And so we’re working through this together. And whether I took the time to explore their goals and values and present prognosis and all these sorts of things impacts the ultimate decision they’re going to be making. And so I think any ambivalence that comes up for me is probably more than likely my own ambivalence. And it’s a flag for me that this idea of being autonomous, like the patient’s autonomy. Autonomy is less of a state and more of an achievement that we achieve together.

I’m going to support your agency and autonomy by providing you with the necessary information to make a decision. You can’t be fully autonomous without the information and my guidance as a clinician. And so I think, we’re offloading too much responsibility onto patients if we claim this is just all their decision and all the ambivalence is theirs. I wonder what other folks think about that.

Eric: It also reminds me, because Alex says every podcast I bring up the nudging podcast that we did on behavioral economics. I’m going to bring it up again today because the phrase I always remember from that one Jenny, which you were on was that word decisional architects, we create the architecture of these decisions, which sounds like Josh was talking about too. And that we are so integral and we nudge people towards particular directions.

Jenny: Yeah, we do. I think Josh is right. I mean, one of the things that is interesting about this category of true ambivalence, you think about the ways out of it. And one way out of it is that the patient does, they work through it and they come to this aha moment of discovery of how to rank their values that seem incompatible. That just often doesn’t happen, right? We’re describing true ambivalence as a state of they’ve done that work and they’re still stuck because there are these things that are really important to them that are incompatible. And so, one way out is to help them to do some choice architecture. And we say this in the paper that this is where having more direct recommendations or nudges or instances of choice architecture are going to be important and called to help the patient out of it.

It’s like that’s their rescue. That’s the way to help them get out. And I’ll say the case that got me really interested in this topic and that I wrote my dissertation on was this case of vacillation that went on for months in the ICU. And the way that it ended, I mean, it was just torture for the family of the patient, the patient, the clinical team. And the way it ended was with a nudge was with all the physicians gathered around this patient’s bedside and a default option was presented for hospice care. And I had really mixed feelings about that because it felt like, well, did the patient really make an autonomous choice? No, but they were truly ambivalent. They weren’t going to get out, and that was what was needed to just move the situation forward.

Eric: Well, I feel like when we’re in this true ambivalent area, if actually look at other literature around choosing jobs or deciding what I want for dinner. Ultimately, one way to get at ambivalence, which may not be a bad thing, is just to make a choice and to recognize not every choice is non-reversible. Even going home with hospice is often reversible and giving people option is that you can come back to the hospital if it’s not working for you, come back.

Now, it’s not always the case. Some choices are very much irreversible, and some may argue every choice is irreversible because you can’t completely reverse a choice. But it also gives me an idea in these situations, one recommendation of a choice is just the time trial. Let’s give it this amount of time and then come up with a firm decision of what to do if things go well or if things don’t go well, there are things that we can do in each one of these ambivalent related phenomenon to move people forward.

And Bry, I want to go to you now.

O. Mary: But Hold on, hold on, hold on.

Eric: Oh, go ahead. Go ahead.

O. Mary: Keep in mind Though, while you’re choosing to not make a choice, you are still making a choice’s.

Eric: That’s a choice.

O. Mary: You are still continuing whatever is going on, good or bad, you are still continuing that. And that does to a certain extent, say that in a way you are making a decision and you’re no longer ambivalent to a certain extent.

Josh: And writing that inertia sometimes allows people to offload responsibility for a decision. So if I make a decision, I’m responsible for the outcome. But if I ride the inertia of what’s already going on, and sometimes people say they put in God’s hands or they have different phrases for this, then I’m not responsible or this is big for surrogates, right? I’m not responsible for my loved one’s death. It’s just what played out.

Eric: And I would say, I’m going to go to Mary because my own personal experience with family members in the hospital. Providers sometimes use that just, we don’t have to make any decisions today. Let’s talk tomorrow. And you have a whole different team tomorrow and they say the same thing and never ends this process of indecision.

O. Mary: And I think this goes to why, I mean, studies have shown that we actually cause families and their surrogates, the patients and their families to end up developing PTSD because we’re like, oh, you have to make a choice, or we’re forcing you into a situation where you have conflicting values. And it’s like, well, should we be doing that? How are we doing that? How are we framing these conversations that end up unfortunately having these bad side effects. Not only for the families, but also for the providers. They end up developing moral distress sometimes too. If you are constantly doing this or you’re not really guiding people in ways that you feel are true to your values or the way you think that things should go, unfortunately.

Eric: Okay. We got a only couple minutes left. I want to make sure we talk about what should we do when we’re in these situations? You recognize there’s ambivalence, do you acknowledge the ambivalence? Let’s think this through, what do we do when there is this ambivalence steps? I love, we have now words that we can attach to it. We’re making hypotheses of what may be going on. How do you each think about this as far as next steps? Bry, I’m going to start off with you.

Bry: Yeah, I mean, Jenny’s mentioned a couple of strategies already. I will say as a clinical ethicist, we always start first with very open-ended questions and try not understand what is going on with the patient. And I will do a lot of validating and naming things in conversations with patients if I can. So I will say to people like, “Hey, it sounds like you’re having a tough time making up your mind about this, is that right?” And sometimes people will be like, yes. And I’ll say, what would help you feel confident about this decision? There’s questions that we can ask. And sometimes we’ve heard directly from people, “I need someone to come in here and tell me what’s going to happen if I do this.” It’s like, “Okay, we can get you that information.” And sometimes it’s, “I just need a little time,” or “I would feel better about this choice if my sister could come and be with me.” There’s things that we can do.

So doing that important exploring work and clarifying work. We mentioned this in the paper, but normalizing it. There are no wrong decisions. A lot of the times, these are very tough choices where there are multiple options that are reasonable or ethically for folks,

Eric: Or there is a bunch of options and they’re all bad.

Bry: Yeah.

Eric: And to acknowledge the negatives, because sometimes I see this a lot with hospice. We talk about how wonderful is hospice? We paint it as this beautiful picture, but we actually don’t never talk about any negatives, especially those that are negative, that are not aligned with their goals. We see this a lot. It’s really easy to forget that somebody’s goals include live as long as possible, and somehow we forget to mention that when we’re using our aligning statements to talk about what’s important to people.

Bry: Exactly. And sometimes I will say that to people like, “Hey, it sounds like you’ve only got a couple of really tough options to choose between. I think it makes total sense that you’re struggling.”

I was thinking too, Eric, listening to you earlier about adaptive preferences as well. So sometimes I think Jenny was mentioning just invite someone to make a leap and make sure we reassure them if they feel like they can make a leap, we are here for you regardless of what happens, and we can have some contingency plans in place, or we can do a time-limited trial and then revisit. But yeah, really trying to dig in, and I think this is part of the work that ethicists and palliative care doctors always do is some of that imaginative work. So trying to get people to engage in some of those hypotheticals. Well, tell me a little more. If we choose this way and this happens, how might you feel? How do you anticipate reacting to that? So trying to dig in and do some of that exploring work, but I would love to hear what others think about responses.

Alex: I’m just going to interject briefly to say again that I think understanding the way that people make these decisions and their psychological capacity to tolerate areas of gray is really important here because some patients just cannot tolerate that gray zone and they need to be given a choice directed towards one state or the other, because anywhere in the middle is just so painful for them.

Josh: Clinicians are that way too.

Alex: Yeah, clinicians. Clinicians very black and white.

Eric: Yeah. I just want to acknowledge, Bry said too is that the feelings, we often don’t talk about feelings with physicians who are ambivalent. And talking about those feelings and acknowledging the negative ones, and also that acknowledging that not everything has to be great or wonderful or there’s bad stuff too. Yeah, Jenny thoughts?

Jenny: I think Bry’s list is great. I mean, I would just add to be cautious of just wanting to too quickly resolve it and just seizing on a glimpse of a decision and pushing that forward. And I know it’s a kind of tough balance of trying to set defaults and give people direction and then not do that problematic, seizing on a moment of apparent choice, but

Eric: That’s one. Just jumping on the choice, maybe just acknowledging, I see that you’re struggling with this. Can you tell me kind how you’re feeling about it?

O. Mary, last couple of minutes? Any other thoughts or suggestions for our audience when dealing with ambivalence?

O. Mary: So I think those same strategies that Bry and Jenny have talked about already also work very well for providers when we’re dealing with their ambivalence, especially the naming it because I feel like they’re such in the moment of clinical care that they don’t really have the time to process what’s going on like a patient may have. So taking them to the side, having that conversation with them and saying, let’s really dig into what’s going on here with you and how you’re relating to what’s going on with your patient. I think it can be really helpful for them too.

Eric: Yeah, trying to find out the source of their discomfort. Right, Josh, I’m going to end with you.

Josh: Yeah, I think all these suggestions are really important. I think the only thing I would add would be for clinicians thinking about you have patient preferences, decisions, making sure they’re all linked up with goals or values. So not having unmoored preferences. I think this is a low-hanging fruit where clinicians sometimes just ask patients what they want or they have unlinked preferences for different care strategies that aren’t linked up to things that are meaningful to patients. And to the extent that we can do that, that can make the decisions more meaningful and help weed out some of the bad ambivalence. The ambivalence is just not relevant for a patient’s goal or value.

Bry: I’m stealing the lost word from Josh, but we talk in the paper about tightening goals up. So instead of saying, well, what do you want? It’s like, what’s more important to you being able to walk for the next two months or being live? So there’s ways to tighten up and get more concrete and how you frame choices and connect them to activities or what the patient’s life will look like, and that can be super, super helpful.

Eric: I love that too. And I just want to acknowledge that Josh also talked about the want statement. There’s a fantasy aspect for that. I want to win the lottery, but something that I value deeply is not wasting money. So I’m not going to play the lottery, but I would still want to win the lottery. So the want question doesn’t really help that much.

I want to thank everybody for being on this podcast. But Jenny, I think we’re going to end a little bit more with the Boston. What was the name of the title of the Boston song?

Jenny: Peace of Mind.

Eric: Peace of Mind. Giving Everybody a little Peace of mind, Alex.

Alex: (singing)

Eric: Perfect song for a great podcast. Josh, Bryanna, Jenny, O. Mary, thank you for being on this GeriPal podcast.

Josh: Thank you.

Jenny: Thank you. Thanks having for having us.

O. Mary: Thank you so much.

Eric: And thank you to all our listeners for your continued support.