by: Jeffrey M. Levine MD, AGSF

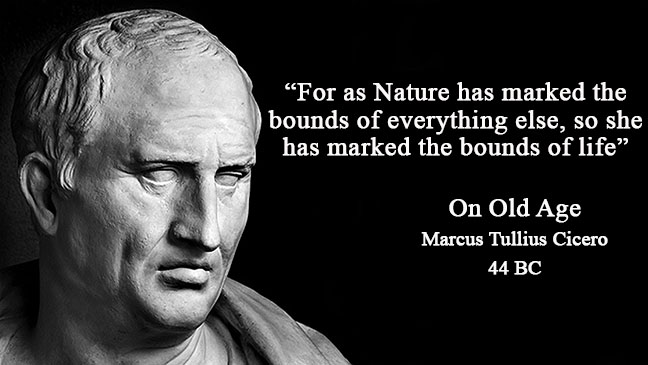

As a geriatrician entering the twilight of my career, I look to the philosophers of my field for guidance on how to navigate my own later years. In addition to contemporary texts and journals I turned toward the ancients and discovered a gem in the writings of Cicero, one of the greatest philosophers of the Roman Empire. The work is entitled De Senectute – Latin for “On Old Age.” Cicero wrote this in 44 BC, the year before he was executed at age 63 by Marc Antony’s henchmen for his alliance with Julius Caesar’s assassins and political opposition to the rulers of Rome.

On Old Age is an optimistic discussion of the spirit of man’s declining years, exploring the relationship with nature and outlining strategies to maximize the enjoyment of life. Old age and death are considered natural components of humanity. Unfortunately he does not discuss the point of view of women, a reflection of Roman culture in which the female gender had lower status – unable to vote or hold political office and largely relegated to managing the home. This flaw, however, does not warrant dismissal of the work.

Born in 106 BC, Marcus Tullius Cicero spent his life intertwined with the politics of Rome, and is considered one of history’s greatest orators. His philosophical writings profoundly influenced Western civilization, including 18th Century Enlightenment theorists such as John Locke, David Hume, and others. Most of Cicero’s philosophical writings were completed after the death of Julius Caesar, when he spent two years peacefully writing in his villa in the ancient city of Tusculum, dictating much of his work to his devoted assistant Tiro, his former slave.

Written in dialogue form, Cicero’s friend Cato is chosen as the principal speaker. Dialogues were a common format in Greek and Roman philosophical writings, having been used by Plato and Socrates. Cicero chose Cato because he was a man who reached the age of 84. Cato addresses the inquiries of Laelius and Scipio, two younger men in their 30’s who seek advice on how best to grow old. Laelius asks Cato:

“(Y)ou will have rendered us a most welcome service… since we hope, indeed wish, at all events, to become old, we can learn of you, far in advance, in what ways we can most easily bear the encroachment of age.”

Cato answers as a stoic – a school of philosophy holding that a wise man should be indifferent to both pleasure and pain, and submissive to natural laws. As such he welcomes the decline of sensual pleasure, replacing it with intellectual and aesthetic enjoyment. Underpinning his answer is that the quality of one’s old age depends upon investments made in earlier years, particularly in one’s health, bodily strength, friendships, and memories of “deeds worthily performed.” He firmly believes that old age has a rightful place in man’s life:

“I am wise because I follow Nature as the best of guides and obey her as a god; and since she has fitly planned the other acts of life’s drama, it is not likely that she has neglected the final act as if she were a careless playwright.”

Cato cites old men such as Plato, who “died, pen in hand, in his eighty first year,” and others who were productive into their nineties and early hundreds. He compares old age to a brave and victorious horse who just won an Olympic trophy.

Through Cato, Cicero defines four reasons why old age appears to be unhappy: 1) It withdraws us from active pursuits; 2) It makes the body weaker; 3) It deprives us of physical pleasures; and 4) It is not far removed from death. He then addresses each reason, arguing for enjoyment and appreciation for old age, particularly in the area of intellectual enrichment:

“It is not by muscle, speed, or physical dexterity that great things are achieved, but by reflection, force of character, and judgement; in these qualities old age is usually not only not poorer, but is even richer.”

Cicero however did not know of dementia the disease, referring to memory loss in old age as superstition, as when Cato says:

“I certainly never heard of any old man forgetting where he had hidden his money! The aged remember everything that interests them, their appointments to appear in court, and who are their creditors and who their debtors.”

Through Cato, Cicero advises to live all phases of life to the fullest, guarding against regret. He recommends that all men “…make a proper use of his strength and strive to his utmost, then assuredly he will have no regret for his want of strength…. In short, enjoy the blessing of strength while you have it and do not bewail it when it is gone, unless, forsooth, you believe that youth must lament the loss of infancy, or early manhood the passing of youth. ”

In his discussion of death, Cato first expresses belief in the immortality of the soul, which was placed inside mortal men by the gods to care for the earth. However he concedes the possibility that the soul may indeed perish along with the body, but is still preserved in the sacred memory of words and deeds.

Whether or not the soul is immortal, Cato firmly accepts the phenomenon of death, with old age as the final scene in life’s drama. In his closing words of advice to his young friends he states, “For these reasons…, my old age sits light upon me… and not only is not burdensome, but even happy.” How different is our contemporary culture that abhors old age and death, where marketing and technology promote false promises of prolonged youth and endless life.

The practice of medicine in the Roman Empire was largely based on the Greek tradition of humoral balance, and relied upon herbal medicines, prayers, and some surgical procedures. Of course there was nothing in the way of artificial life support, a phenomenon based upon science and technology that was developed the 20th Century. Modern medicine is largely structured upon preservation of life at all costs – a philosophy that simply does not apply to many of our patients, particularly when it incurs needless suffering in advanced age. We can learn so much from Cicero’s outlook, not only with medical decisions to prolong life, but in how we structure our own lives in preparation for old age, and how we live it from day to day.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

For a complete copy of Cicero’s On Old Age click here.

For a good reference on the life of Cicero Click here.

For an engaging novelized trilogy on Cicero’s life see Robert Harris’s books entitled Imperium, Conspirata, and Dictator.

For an excellent introduction to the topic, see The Cambridge Companion to Greek and Roman Philosophy, edited by David Sedley.