by: Kelley Babcock, MS, CCC-SLP, BCS-S, @kelleybabcock

The #thickenedliquidchallengehas certainly raised awareness of how difficult it can be for patients to enjoy honey-thickened liquids. Many physicians and speech pathologists have never tried the liquids they so frequently prescribe to patients, so this increased awareness may help initiate important conversations with patients, clinicians and family members about quality of life and patientʼs rights to decline recommended interventions.

Unfortunately, this challenge has been named the “thickened liquid challenge,” which could be confusing for patients who find these videos on YouTube. A more accurate name would be the “honey-thick liquid challenge.” While I almost never recommend honey-thickened liquids (see my blog here for rationale), I do recommend nectar-thickened liquids with appropriate patients. I do this judiciously and using the following decision-making process:

- Does the patient show consistent aspiration on an instrumental evaluation of swallowing?

- Is there a significant reduction in aspiration with trials of thickened liquids during the instrumental evaluation?

- Is the patient at increased risk of pulmonary infection? (see blog post here on factors other than aspiration that place patient at risk for pneumonia)

- Have I attempted compensatory modifications that have been unsuccessful in eliminating aspiration (e.g.: postural techniques, improving sensory awareness, and modifying the volume & speed of food presentation)?

From this algorithm, I can present the patient with an objective diet recommendation as well as the rationale behind the recommendation. The patient then has the opportunity to ask questions and communicate their wishes regarding the diet, and finally a diet is ordered based on this shared decision-making interaction.

Diet modification should be the last compensatory strategy utilized in management of dysphagia (Logemann, 1998), but it is a reasonable and appropriate recommendation for many patient populations. The participants in the #thickenedliquidchallenge make the recommendation of a thickened liquid diet look impossible to complete, but as I watched the videos, I kept thinking to myself, “they are doing this all wrong!” I completed a 12 hour challenge and drank over 80 ounces of fluid without getting sick, overly thirsty, overly full or feeling dry. I also didnʼt drink anything that could be called “gross,” “goopy,” or “sludge.” Below are a few recommendations for SLPs, physicians and patients on how to succeed on a thickened liquid diet.

1. Change your thickener. The most common thickener I saw used in the #thickenedliquidchallenge was the super cheap cornstarch-based thickener that is found at the local pharmacy. Though this thickener will certainly do the job, it can also turn your beverage into sludge. Because cornstarch continues to thicken over time, what was initially created to be a nectar-thickened liquid may become pudding-thick

after sitting around for a while. Cornstarch-based thickeners are also more difficult to use with carbonated beverages and can thicken way too much with hot liquids.

Xanthum gum-based thickeners are a newer breed of thickener which maintain a more consistent viscosity (thickness) across time, temperature and base fluid (Mills, 2008). They have been found to have a more “slick” feeling in the mouth which is reportedly more pleasant for consumption. Unfortunately xanthum gum-based thickeners are more expensive and many facilities refuse to transition to them.

Many of my patients prefer pre-mixed thickened fluids. They maintain their viscosity over time and are a consistent, convenient option.

Below are two 4 ounce glasses of nectar-thickened liquid after sitting for 45 minutes. The image on the left is the xanthum gum-based thickened liquid while the goop on the right is the cornstarch-based thickener.

2. Prepare thick liquids correctly. This may seem silly, but make sure that the amount of thickener and liquid is correctly measured when mixing up thickened liquids. Most thickeners come with measuring spoons right inside or are in individual packages for single use. If your thickener does not have a measuring spoon, grab one out of the kitchen drawer & leave it in the container for easy measuring. I recommend patients use shaker bottles that have ounces printed on the side so they can quickly identify the correct amount of liquid to prepare. These bottles are sold in grocery stores, and if the patient wants to be really fancy, they can pick up a bottle designed for protein shakes – these are quite large & have a mixer component within so consistent mixing is easy. If the liquid does not look to be the correct thickness, check the directions to ensure you have allowed the thickener enough time to work – donʼt just keep adding thickener.

3. Go naturally thick. Many liquids are naturally nectar-thick. Nectar-thick liquids should have a viscosity, or thickness level, of 51-350cP (centipoise). I recommend fruit

nectars (peach, apricot), Kefir, Kroger brand yogurt smoothies, thick tomato juice & soup and buttermilk. Many of the oral nutritional supplements found in hospitals are also nectar-thick. Resource Health Shake (150cP), Resource 2.0 (70cP), MightyShake Regular No Sugar Added (51-350cP), ProMod Liquid Protein (51-350cP), Carnation Instant Breakfast Lactose-Free Very High Calorie (95cP) are all nectar-thick without adding any thickener (Olsen & Kavlich, 2011).

4. Tips for improving mouth moisture. One of the major complaints from the #thickenedliquidchallenge participants was that their mouths felt very dry. I recommend ice chips and small spoonfuls of water after good oral care for patients who are on thickened liquid diets. Our lungs can tolerate small amounts of aspiration of water (Coyle, 2011). What they do not tolerate well are large amounts of aspiration of soda, coffee and juice. There are a few lines of oral moisture products – mouth sprays, mouthwash, gum, toothpastes – that can help the mouth feel less dry. Good oral care also helps keep the mouth feeling moist and helps protect against pneumonia.

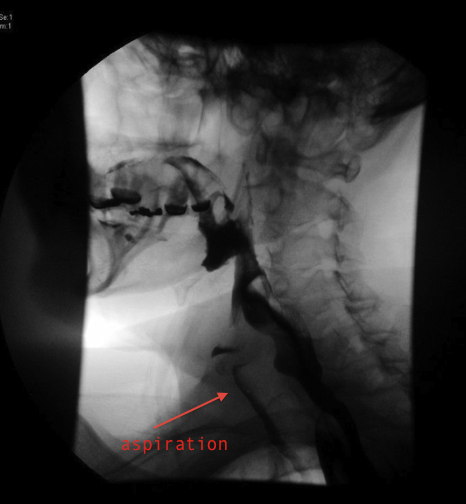

Thickened liquids themselves have not been found to “dehydrate” patients on their own. In 2007, Sharpe and colleagues found that both cornstarch- & gum-based thickeners released 95+% of their fluid content in both rat and human trials. What the #thickenedliquidchallenge sought to highlight was reduced oral intake of fluids when patients did not prefer the liquids they were prescribed. While this certainly can occur, we as clinicians must ensure that patients understand the risk they are taking when refusing a prescribed diet. The patient in the image below did not believe that he had any difficulty swallowing. He had been hospitalized three times in one year for pneumonia – once with sepsis, but never coughed or had any overt signs of aspiration during mealtime. On modified barium swallow study, he was found to have profound dysphagia with thin liquids, but was able to significantly reduce the quantity of aspiration when his liquids were thickened to nectar-thick. He did great with a nectar-thickened liquid diet and has not had pneumonia since.

Remember that even though thicker liquids may seem to be less pleasant to you, aspirating and coughing throughout a meal is also not pleasant. Each patient deserves our thoughtful consideration of their present situation, prognosis, and wishes when determining their personal diet recommendations. Just as no clinician would recommend that every patient with dysphagia be placed on a thickened liquid diet, no clinician should say that patients should never be placed on one. Many more studies of the long-term outcomes of the use and non-use of thickened liquids in dysphagia are needed, and I invite the geriatric community to join us in the speech pathology world to engage in these investigations. We speech-language pathologists need to engage with patients, families, and other team members to implement evidence-based practice, support ethical decision-making, and provide good guidance in the implementation of thickened liquids so that any negative impact on quality of life can be minimized or avoided and any expected benefits fully realized (Balandin, Hemsley, Hanley, & Sheppard, 2009).

References

- Balandin, S., Hemsley, B., Hanley, L., Sheppard, J.J. (2009, September). Understanding mealtime changes for adults with cerebral palsy and the implications for support services. J Intellect Dev Disabil. 34(3):197-206.

- Coyle, J. (2011, December). Water, Water Everywhere, But Why? Argument Against Free Water Protocols. SIG 13 Perspectives on Swallowing and Swallowing Disorders (Dysphagia). Vol. 20, 109-115.

- Logemann, J. A. (1998). Evaluation and Treatment of Swallowing Disorders, (2nd Ed.), Austin, TX: Pro-ed Publishers.

- Macqueen, C. E., Taubert, S., Cotter, D., Stevens, S., & Frost, G. S. (2003). Which commercial thickening agent do patients prefer? Dysphagia, 18, 46–52.

- Mills, R. H. (2008, October 14). Dysphagia Management: Using Thickened Liquids. The ASHA Leader.

- Olson, E & Kavlich, S. (2011, November). Viscosity Levels for Oral & Enteral Feedings. Retrieved from http://www.nutrition411.com/content/viscosity-levels-oral-and-enteral- feedings

- Pelletier, C. A. (1997). A comparison of consistency and taste of five commercial thickeners. Dysphagia, 12, 74–78.

- Sharpe, K., Ward, L. Cichero, J., Sopade, P., & Halley, P. (2007). Thickened fluids and water absorption in rats and humans. Dysphagia, 22, 193-203.