What happens in Long Term Acute Care Hospitals, or LTACs (pronounced L-tacs)? I’ve never been in one. I’ve sent patients to them – usually patients with long ICU stays, chronically critically ill, with a gastric feeding tube and a trach for ventilator support. For those patients, the goals (usually as articulated by the family) are based on a hope for recovery of function and a return home.

And yet we learn some surprising things from Anil Makam, Assistant Professor of Medicine at UCSF. In his JAGS study of about 14,000 patients admitted to LTACHs, the average patient spent two thirds of his or her remaining life in an institutional settings (including hospitals, LTACs and skilled nursing facilities). One third died in an LTAC, never returning home.

So you would think with this population of older people with serious illness and a shorter prognosis than many cancers, we would have robust geriatrics and palliative care in LTACs? Right? Wrong.

3% were seen by a geriatrician during their LTAC stay, and 1% by a palliative care clinician.

Ouch.

Plenty of room for more research and improvement. Read or listen for more! See also this nice write up by Paula Span in the New York Times, and this prior study on geographic variation in LTAC also by Anil.

Please also note that our 100th podcast approaches! Please call 929-GERI-PAL to let us know what is working and what can be better about GeriPal. You might make it on the air!

by: Alex Smith @AlexSmithMD

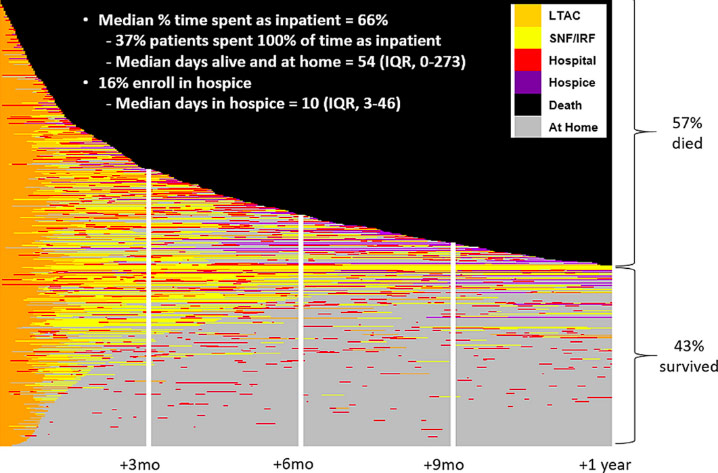

P.S. Here is the figure from Anil’s paper that we gush about on the podcast:

Eric: Welcome to The GeriPal PodCast. This is Eric Widera.

Alex: This is Alex Smith.

Eric: Alex, who do we have in the room with us today?

Alex: In studio today we have Anil Makam who is a hospitalist and researcher at The Chan Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital.

Eric: Chan Zuckerberg.

Alex: The Chan Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital.

Eric: Did Mark Zuckerberg change his name?

Alex: No, no. This is Priscilla Chan.

Eric: Oh.

Alex: She’s a UCSF doc.

Eric: Ah.

Alex: Right?

Anil: That’s right.

Alex: Welcome to the GeriPal PodCast.

Anil: Hey, guys.

Eric: We’ve got to call it the CZSF-

Anil: The CZSFGH –

Alex: That’s too many. The General.

Eric: The General. We’re going to be talking about LTACHs, or long-term acute care hospitals. Did I get that abbreviation right?

Anil: That’s right.

Alex: I think it’s “Letack”.

Eric: “Letack”?

Alex: “Letatch”.

Eric: Yeah.

Alex: You’ve never heard that before?

Anil: Yeah, the cool kids say “L-TACS”.

Alex: LTAC.

Eric: LTACs. What they are, who goes to them, and what happens to these people. But before we do, we always ask for a song request. Do you have a song for Alex?

Anil: We do. In honor of where this research came from, Deep in the Heart of Texas. The de facto state song.

Eric: Are you going to sing along with Alex?

Anil: I will try.

Eric: Okay.

Alex: Perfect. (singing).

Alex: Whoo!

Eric: Whoo! Wee-haw!

Eric: That was fabulous. Texas, this started off in Texas?

Anil: Where my research career started and where the idea to study LTACs came from. Was practicing in Texas, and then moving to San Francisco, and it’s black and white in terms of post-acute care use.

Alex: What do you mean by “black and white in terms of post acute”?

Anil: Well, we should back up. Shouldn’t we talk about what is an LTAC?

Eric: Okay. What is an LTAC?

Anil: An LTAC briefly is a post-acute care hospital for people who survive either acute or serious illness in a hospital, but still need on the order of three to four to five weeks of more hospitalization, and aren’t ready to go home, and are too sick to go to a skilled nursing facility.

Eric: Okay. What’s the difference between that and a skilled nursing facility?

Anil: It’s closer to a hospital. Nurses have a smaller patient-to-nurse ratios. Physicians see patients daily as opposed to skilled nursing facilities, where they’re mandated once every few weeks, and more so people are sick.

Anil: Also an LTAC, there’s a multi-physician specialty available on a daily basis. Some have small operating rooms; they have an ICU, they have usually a CAT scanner. And they have the ability to do laboratory tests as needed.

Alex: Is this the same thing as a vent facility?

Anil: Good question; that’s where they originated from in the ’80s. They started as vent hospitals and morphed into more general broad post-acute care hospitals.

Eric: The difference between this and an acute rehab?

Anil: Here they’re focused on medical care, as well as rehab, and not solely on rehab, which is the main distinction. They don’t have to have three hours of rehab a day, which is one of the criteria to go to an inpatient rehab hospital.

Alex: So, LTAC. You said earlier that it’s black and white, as far as the difference between Texas and California in terms of LTAC facilities. Can you expand on that?

Anil: Yeah. It’s more so between Dallas-Fort Worth as compared to the Bay Area. In the Dallas-Fort Worth Metroplex, when I was practicing there, we had on the order of 20 to 25 LTAC hospitals. It was normal for people, after they were recovered from the hospital, to go to an LTAC to recover.

Anil: In San Francisco, if you include Marin County, San Francisco, the South Bay, the East Bay, even all the way out to Sacramento, there’s about four LTAC hospitals.

Alex: Oh, that’s it?

Anil: That’s right. It’s not part of the normal part of post-acute care, at least in the Bay Area.

Alex: Is that because we keep our patients healthier until they’re discharged from the hospital?

Eric: It’s all that kale that we eat.

Alex: That’s right.

Anil: I think it’s just representative of just how different markets think of post-acute care. Interestingly, 70, about three-quarters of the variation in the Medicare spending, of Medicare spending, is attributed solely to post-acute care. This is reflective, I think, of the national experience.

Anil: Some places use more expensive post-acute care settings like LTACs. Other places keep people in the hospital longer, or send them to skilled nursing facilities.

Alex: So over two-thirds of geographic variation.

Anil: Three-quarters of the geographic variation-

Alex: Oh, three-quarters.

Anil: … in Medicare spending is due to how different places use post-acute care.

Alex: And LTACs are much cheaper than skilled nursing facilities?

Anil: We would hope so.

Alex: Yeah.

Anil: But you think, yeah, far more expensive. For the same diagnosis, it’s about three to five times more expensive than a skilled nursing facility.

Alex: LTAC is three to five times more expensive than a skilled nursing facility-

Anil: Exactly.

Alex: … for the same diagnosis.

Anil: Yep.

Alex: Whoa. Why do states have these? What’s going on in Texas?

Anil: So, good question.

Eric: They like it big in Texas.

Anil: Actually, the regulation in Texas and California are the same, as in we don’t have Certificate of Need laws in either state.

Alex: Wait, what?

Anil: Meaning that if you wanted to open a new hospital or an LTAC, certain states actually require you to make a case, which is a Certificate of Need. Actually, I was actually surprised California doesn’t have a Certificate of Need requirement either to open up a facility.

Eric: And LTACs are basically regulated like a hospital. Because it is a hospital. Right?

Anil: It is a hospital.

Eric: Long-term care hospital.

Anil: Hospitals have to meet criteria by CMS, which is the Centers of Medicare/Medicaid. LTACs have to meet the exact same criteria as acute-care hospitals or traditional hospitals, which most people are familiar with. Except the only distinction is they have to have an average length of stay of 25 days for their population.

Eric: That’s the long-term care part. The long-term acute hospital part is that you have to have a length of stay of 25 days.

Anil: Yeah, it’s a little bit like jumbo shrimp, and an oxymoron. The long-term acute part, at least, for people who have acute needs, but they need to be there for, on the order of several weeks.

Alex: Should we think of them; for those people who haven’t been in one, should they think of sort of like an ICU Lite? Or more like an intense skilled nursing facility?

Anil: When used appropriately, I think the best comparison are ICU/step-down hospitals. Once people recover from ICU, but still have acute needs, as well as the ICU-level care as well.

Eric: Okay. How did you get interested? What’s the nidus for this?

Anil: Yeah, when I was a fellow here, a lot of my colleagues used to moonlight at LTACs. The funny thing, I was looking for moonlighting opportunities so I was able to afford San Francisco rent. People looked at me like I had two heads on my shoulder when I set out. Where do people moonlight? I just threw out LTAC because that was a familiar setting to me. And they’re like, “What the heck’s an LTAC?”

Anil: Then when I went back to Texas on faculty, that idea just stayed with me, because I’ve taken care of sick old people in both places. But for some reason, the way we think about post-acute care was very differently in different markets.

Eric: You had a previous paper in the Journal of American Geriatrics Society, JAGS, that showed that the use of LTACs is determined mainly by geography? Is that right?

Eric: Or a lot of the variation?

Anil: … a lot of the variation. I’m not mostly, half of the variation and who goes to an LTAC is still driven by how sick people are and what their care needs are.

Anil: But if we think about variation and other things in healthcare, 50% is pretty low. If you think about what the variation in the inpatient mortality or inpatient Medicare spending, less than 10% for the variation is explained by things other than how sick people are.

Anil: So that’s a lot of variation that’s not explained by how ill people are, and what they actually need. About a third of the variation is just what region of the country you’re in, and 15% of the variation is what hospital you’re in before you go to an LTAC.

Alex: Oh, so some hospitals tend to send patients to LTACs and some hospitals tend not to.

Anil: Exactly. If you’re in a market with a lot of LTACs, you could be in a hospital that preferentially sends people there, or you could be in a hospital that rarely uses it, even with the same access.

Alex: There must be some reason for some regions and hospitals linking up with LTACs and others not. It doesn’t have to do with money, does it?

Anil: I’ve never been able to really answer this. I’ve talked to researchers and some industry insiders. The best answer I can get to is just some places have an appetite for them, and have experience. There’s some upfront construction costs and maintenance costs; I think it’s a lot more expensive to maintain a hospital in San Francisco than it is Dallas. But that’s not the full story. It’s not really clear why some places have a ton of these and some places don’t.

Eric: Does it matter at all if you have an LTAC within your hospital, or with, outside of your hospital?

Anil: CMS is trying to draw that distinction. If you have a … Some hospitals, some LTAC hospitals are considered hospital within hospitals, where they lease a floor, within a traditional hospital. Then about half the LTACs are free-standing facilities, just like a traditional hospital.

Anil: CMS tries to say, to limit self referral, that you have to have separate management for the LTAC. They can’t be affiliated in any way, shape, or form. Then there used to be, I don’t know how strictly it’s enforced, but only a certain percentage of their population could come from the hospital that they’re leasing.

Eric: But there’s still that financial relationship of you have this potentially lucrative lease, and you want that lucrative lease to stay, probably.

Anil: Yeah, one of our main findings in our variation work is proximity to the nearest LTAC, from where you’re hospitalized. We would consider that a zero-mile distance, if you’re located in the same places. That’s one of the strongest predictors of who goes to an LTAC.

Eric: How close you are.

Anil: How close you are. If you’re in a building with an LTAC, some of this might be just familiarity. Some of the reasons could actually be good intentions; continuity. Sometimes a physician, specialty physicians might still go and consult on their patients who move from one floor to the other.

Alex: Earlier you said that the patients who go to the LTACs are patients who need more time in the hospital. But they only need more time in the hospital if their goals are aligned with acute type of care; intensive care, if you’re going to trach in a PEG and they are comfortable being ventilated and being weaned from the ventilator, though that may take months … but that they’ve all had discussions about prognosis, I’m sure, and know what’s ahead for them, and are fully informed as they’re making these decisions to go to an LTAC. Is that right?

Anil: You sound very optimistic. That’s the idea. Before you go to any, the next setting, the hope is, especially if you’re that sick, people have had discussions with their doctors, with their loved ones, and have thought about what they’re willing to live with, what kind of life is acceptable, what kind of impairments are acceptable, what kind of care is aligned with their goals.

Anil: That’s something that in the current paper, we get at not directly, but indirectly, and something that we’ll become increasingly interested in looking at.

Eric: Let’s talk about the current paper. You just published a paper about a month ago in the Journal of American Geriatrics Society, JAGS, titled The Clinical Course After Long-Term Acute Care Hospital Admissions Among Older Medicare Beneficiaries. I did not memorize that; Alex is hold up the paper for those who are watching on YouTube.

Eric: It is an absolutely fabulous paper. It gives us a sense of who are these people, and what happens to them in LTACs? Are they getting better? For most people, I think probably the goal is, “Let’s get my loved one home. I want to go home.” Are these people actually going home? What’s happening to them? Overall, are they getting better?

Eric: What did you find? Are they getting better when these people are going to LTACs?

Anil: Yeah, we looked at a sample of Medicare beneficiaries, using the national Medicare dataset. We looked at how people did up to five years after they go to an LTAC hospital. We followed them out for whether they lived or died; we’ve looked at their inpatient utilization burden; and we looked at whether people made it “home” even though we don’t actually know they went home.

Anil: We found that unsurprisingly, mortality rates are really high. About fewer than 1 in 5 older adults are alive five years after they go to an LTAC.

Alex: Fewer than 1 in 5 are alive how many years?

Anil: Up to five years.

Alex: Up to five years after an LTAC.

Anil: And the one-year mortality is fairly high, a little over half of older adults die by one year.

Alex: Wow.

Anil: I think what stood out to me most was just the intensity of care people received after they went to an LTAC.

Eric: And you had one of the most beautiful diagrams … I swear, I stared at it for like a half an hour. It was a heat map looking at … each line was like individual patients.

Eric: You can actually see black was if they died, orange was they’re in LTAC, and you can actually see for these individuals who survived. 40% survived at one year. You can see they were in LTAC; then the color turned gray, which is if they went home. Then they went to the hospital, then went home, then went to the hospital, they went home, they go to the hospital, they go home … the cycle just continued.

Eric: And those were like the people who did the best after LTAC, versus half of them died. And those people spent, it looked like most of their time in an inpatient facility. Is that right?

Anil: Yeah. Thank you for highlighting our figure; I spent a lot of time trying to tell the story.

Eric: I loved that figure. It is something that, really, all of our listeners should check out. It’s one of those things that you can just stare at and stare at and stare at and learn more and more about.

Alex: Right. If you’re interested in the visual display of quantitative information, this is a figure you need to see. This really conveys the message.

Eric: Well, it’s interesting. For like the first 30 seconds I’m staring at it, I’m all, “What am I staring at?”

Alex: Yeah.

Eric: Then you start realizing that these colors are, “Oh my God, that’s a hospital stay, that little band of red. That big black splot-”

Alex: They should have printed it bigger, though. It should have been half a page.

Eric: You can actually go online, you can actually pull out the big graph-

Alex: Yeah.

Eric: … which is really amazing to look at. We’ll have a copy of it attached to the Show Notes of this podcast.

Anil: I was glad at least JAGS published in color. It doesn’t do it justice when it’s in black and white.

Eric: No, that would be very boring.

Anil: Yeah, I’m a health services researcher, and I focus on a lot of comparative effectiveness research techniques. But I personally think that sometimes telling the best story is just in the descriptive data.

Anil: We used claims data and pieced together where people were every single day after they went to an LTAC, just based on the dates of their claims. We tried to tell the story of what happens to people using a 30,000-foot dataset, without actually interviewing and talking to people.

Alex: Yeah.

Eric: I think that’s the important part, just knowing half died, doesn’t tell the story. Knowing that … what was their median survival?

Anil: Median survival eight months for all comers.

Eric: That’s worse than most … almost every cancer out there now.

Anil: Yeah, yeah –

Eric: … pancreatic cancer. That’s probably about the same.

Alex: Probably about the same.

Eric: Survival. Yeah.

Alex: Current treatments.

Anil: Yeah, we can get into it more. But in the population that’s probably going to be more representative of LTACs moving forward, it’s a median survival of a little over six months. Which is close to the hospice criteria.

Alex: Wow.

Eric: That is basically anybody who’s eligible for an LTAC, is eligible for hospice.

Alex: Now, presumably, these people who are going to these LTACs are, they have a goal that’s different from people who are going home with hospice.

Anil: Yes.

Alex: In some sense. Their goal is to receive this aggressive treatment in hopes of living longer. And for many of them, hopefully, returning to better function and to get home.

Anil: I would say a slight twist is that’s the goal of the care; we actually don’t know if that’s the goal of the patient.

Eric: Well, I would-

Anil: Assuming it’s the goal of the patient.

Eric: Well, I would argue if the variation is dependent on proximity and geography, sure, maybe some of that is related to … like, maybe people in different proximities to an LTAC have different goals? But, that certainly would be weird if they’re all geographically in the same city.

Eric: That variation, it argues from the Dartmouth Atlas literature too, is, preferences for care don’t really matter. It’s the systems that we build that determines what kind of care we get.

Anil: Yeah, I mean, I think that’s an interesting hypothesis that-

Eric: Dammit, it’s a hypothesis.

Anil: But we don’t know, because nobody has ever actually went into these facilities and spoken to people, or even before they leave the facilities, is this the care they want? We’re assuming that this is the care and aligned with their goals, because these are hospitals. They’re not hospice facilities. They’re not intended to focus on quality and to transition from less intensive care.

Alex: Yeah, I’m wondering what proportion died, lived less than six months.

Anil: What proportion …

Alex: I don’t know, you probably don’t know that off the top of your head. But it’d probably be something like a third.

Anil: It’s probably, a third of the people never make it home. They don’t necessarily die in the LTAC, but they’ll go from an LTAC to a hospital, maybe back to the LTAC, or a skilled nursing facility, and they’ll die somewhere along this continuum of care.

Anil: We know the average survival, median survival, is six to eight months, depending on-

Alex: Wow.

Anil: … if you’re thinking the older LTAC population compared to the LTAC population of the current.

Alex: These people are seriously ill. They’re in these LTAC facilities. They’re older; these are GeriPal patients, right?

Anil: Yep.

Alex: They, I’m so relieved that we have robust palliative care services in all of these LTACs.

Eric: Are they getting palliative care?

Anil: Our study would argue very little penetration of palliative care, if you believe how we define palliative care, which-

Eric: I think we can find it.

Anil: We use Medicare billing data, physician pro-fees, or professional fees, which is in the Medicare Part B data.

Anil: Medicare requires physicians to designate their specialty. If you’re a palliative care physician, and you want to bill, and you’re part of the same group as a group of internists, and you’re both seeing a patient and you both submit bills on the same day, to differentiate your care from your colleague’s care who’s in your group, you would submit a designation that says you’re a palliative care physician. So both of you get paid.

Eric: So if I, before the LTAC, I saw a patient as a palliative care physician in the hospital, that would have been captured by this definition.

Anil: It’s never been validated, I should say. But I think it’s a reasonable way, because doctors care about how they get paid.

Alex: We need to validate this, because there’s a virtual billing code for palliative care, but it’s a v-code, and so it does not, there’s no reimbursement for it. There’s no incentive to bill for it. But it would be fascinating to validate this measure.

Eric: But if a nurse practitioner and a social worker, they saw them, they wouldn’t have been captured.

Anil: Would not have been captured. We only had physician data. There could have been palliative care delivered by a nurse, a social worker, psychologist, other members of the team.

Eric: How many of these patients with a median survival-

Alex: Eight months.

Eric: … eight months, saw palliative care physicians?

Anil: A whopping 1%.

Alex: 1%.

Eric: 1 out of 100.

Alex: 1 out of 100.

Eric: And that was at any time during the-

Anil: Only during that index episode of care, which we defined as when they’re in the hospital and then in the LTAC, when they get transferred.

Eric: So even in the hospital-

Alex: Oh, this includes the hospital too?

Anil: This includes the hospital.

Eric: Yeah.

Alex: Whoa. Whoa!

Anil: Yeah.

Alex: It’s even worse. Oh, no.

Eric: Yeah, that’s not good. But, but, you also included-

Alex: He included-

Eric: … geriatricians, too, right? You looked at it and you said, “Hey, geriatricians got some training in communication and aligned care.” What, half of them? These are all Medicare patients, right?

Anil: About 4%.

Alex: 4%.

Eric: 4%. Hey. There we go.

Alex: Let’s say this billing code is underestimating the rates of palliative care and geriatrics by a factor of five. It’s actually 5% to palliative care, and 20% to geriatrician. But still abysmal.

Eric: I’m guessing that actually most of these palliative care consults happen in the hospital because penetration of palliative care into LTACs is abysmal. I don’t know the data, but I’m trying to think of any setting that does-

Alex: Yeah, I’ve heard of one palliative care doc who works in an LTAC.

Anil: Yeah, it’s not a common, I don’t think it’s a common phenomenon. Something we’re actually looking at now is what’s the palliative care penetration in LTACs in California?

Anil: There’s a dataset, that’s public available, that says how many palliative care-trained professionals and LTAC employees and across the, I’ll give away one of our main findings; across 19 LTACs in California, there’s one palliative care social worker.

Alex: Whoa! Across 19 LTACs in California, there are no palliative care physicians, no palliative care nurse practitioners, there’s one palliative care social worker.

Anil: At least employed and reported to OSHPD, which is the agency that reports on physician staffing or healthcare professionals.

Eric: This is really fascinating. These are hospitals, and when we look at CAPC data around penetration of palliative care in hospitals, you can see that over the last 15 years, penetration; 90% of hospitals, large hospitals, have palliative care. That data, I believe, excludes LTAC.

Eric: Nobody is looking at LTACs, and the penetration is probably close to 0% for these … Part of the growth of the inpatient hospital palliative care is that there was a financial incentive for hospitals, if we actually talked to patients about their goals, many times their goals are not aligned with very very aggressive care at the cost of everything else.

Eric: Is there that same financial incentive for LTACs to consider things like palliative care as a way to help people elucidate their goals, which also may come at a cost for shorter lengths of stay at LTACs?

Anil: Great question. I would say not explicitly, but as we’re moving to an ACO model, the Accountable Care Organizations, if a Medicare beneficiary is part of that, I think there would be an incentive to increase the palliative care footprint in post-acute care settings, even beyond LTACs.

Eric: Yeah, and I also look at your beautiful heat map again, because I can’t stop staring at it. I’m in love with your heat map. I just, I want to print out a big version and put it on my wall.

Anil: Maybe you should marry it.

Eric: Yeah, I’m thinking about it. But it’s interesting that the orange LTAC color is right about one month, maybe 25 days. They disappear. I don’t see any orange past a month. And I see a lot of orange at a month. Why is that?

Anil: I think a lot of it has to do with patient selection, as well as how LTACs are defined. An LTAC is distinguished from an acute care hospital only by their length of stay. Their average length of stay for the entire population, not for any individual patient, has to be 25 days to maintain certification as an LTAC.

Eric: So LTACs are master prognosticators. They can actually, they know when they get a referral to see a patient, this patient will stay on average, 25 days. And we’re really-

Alex: That must be it. It could be that they just charged them at 30 days.

Eric: We are really good at it because that line, Alex, take a look at this line! Right there!

Alex: I see it. I see the line.

Eric: It’s remarkable, how amazing a prognosticator is.

Alex: What the analogy here is with the skilled nursing facility to Medicare, post-acute skilled nursing facility benefit, where you have 100 days of coverage. But only the first 20 days-

Eric: Is covered.

Alex: … are completely covered by Medicare. After that, you have a copay. So what’s the average of length of stay? It’s like 21 days.

Anil: 20 days.

Alex: It’s right there, right?

Eric: You see this huge dropoff.

Alex: Right.

Eric: At that.

Anil: Yeah, no, this has been looked at. Once people cross that magical threshold, the discharge rates do spike. Not as high as you actually would expect, but you might see somewhere around 8 to 10% of people get discharged right at that 25-day threshold.

Anil: But yeah, so I think the sweet spot for LTACs are finding people who are sick, but stable, but don’t need forever inpatient care. Those are people that I don’t think LTACs are necessarily interested in caring for.

Alex: Now, do we-

Eric: It looks like in the heat map. They don’t do that. I don’t see, I mean, there may be an orange line in there that crosses three months? But I am having a difficult time seeing any of that. Again, most of them, there is a, almost a wall of orange that stops at about one month.

Anil: Yeah. I would say, even though they don’t, they might not need to be in a hospital, or should be or want to be in a hospital, most of these people do go on to further post-acute care.

Eric: Yeah.

Anil: They’re not necessarily going home; they’re going, the most likely destination, if they’re alive, is a skilled nursing facility.

Eric: Right. How much of the remainder of their life do they actually spend in inpatient post-acute settings?

Anil: On average, people are spending two-thirds of their remaining life in some kind of inpatient setting. Whether it’s a hospital, skilled nursing facility.

Eric: Wow.

Alex: Two-thirds.

Anil: Then a little over one third will never make it home. They will not necessarily die in the LTACH, but die in some kind of hospital or inpatient setting.

Alex: Do we have a sense of what the symptom burden is for these folks in LTACs?

Anil: Not great. There’s a couple small studies. The one that comes to mind is a great qualitative study of chronically critically ill patients with tracheostomies. And it’s, as you would imagine, a very high symptom burden in this population.

Eric: Do we have an idea of the amount of life-sustaining or intensive life-sustaining treatments that these individuals are on? Or base of artificial life-sustaining treatments, PEGS, trachs, things like that?

Anil: We do. We looked at the burden of artificial life prolonging or intensive therapies. We looked at tracheostomies, Reseda dialysis, permanent feeding tubes; not necessarily NG feeding tubes. And about a third of people get one of these, mostly in the hospital, but also in the LTAC when they go.

Eric: And from a prognosis, we talk about hospice, these individuals; that the sickest group have a median survival of six months. Overall, the group has a median survival rate of eight months. So hospice seems appropriate for most of them. While they may not be getting palliative care, do they have access to hospice? And do they use it?

Anil: I would say since they’re Medicare beneficiaries, they theoretically have access to hospice. But we had found only 16% will enroll in hospice in that first year, before dying. Just for comparison, in the national Medicare experience, close to half of beneficiaries will enroll in hospice at some point before they die.

Eric: And the, do you have an idea, like median length of stay in hospice? Because these people are way more expert prognosticators; we know they’re only go to stay in a LTAC for 30 days, so we have a really good idea of prognosis for these individuals. They must stay there longer in hospice though, length of stay in hospice must be longer, because of that expert prognostication skills?

Anil: We would hope. We’re close to 10 days on average.

Eric: And that’s about half-

Anil: Half.

Eric: … of what we see in the general population of hospice?

Anil: Yeah. I’m sure you guys think the general average is probably shorter than it should be, which is around a little over three weeks.

Alex: Yeah.

Anil: This is about 10 days.

Eric: Wow.

Anil: On average. And this isn’t just an issue at the LTAC; this is even after they go to an LTAC, I mean, after they leave the LTAC. This is when they’re back in the hospital, in the skilled nursing facility, kind of like I alluded to. These people are spending two-thirds of their remaining life in some kind of inpatient setting. There’s a lot of opportunities and contacts along the way.

Alex: With healthcare reform, and bundled payments, hospitals and health systems are increasingly responsible not just for the care in the hospital, but also for the post-acute care.

Alex: My understanding is that much of the cost savings that health systems are trying to achieve in order to meet these new bundled payment incentives, is by reduction in post-acute care. I’m wondering if there’s been an impact on LTACs in particular.

Anil: From acute care, from Accountable Care Organizations?

Alex: Yeah, from Accountable Care Organizations, bundled payments, healthcare reform.

Anil: I think it’s influencing, we see it in probably more the Medicare Advantage. We’re not seeing, but assuming, because that’s not data that is available until recently.

Anil: But I think the idea is Accountable Care Organizations, their biggest impact in savings is through reduction of post-acute care. Typically through skilled nursing facilities and home health. I don’t think LTACs have necessarily been on the radar.

Alex: Okay.

Anil: Largely because the population’s much smaller. But if you look at their subsequent utilization, I would imagine these are folks who would be in the highest spending group, “high users” of healthcare.

Eric: Medicare’s looking into LTACs, right? You mentioned site-neutral payment policies. What’s that?

Anil: Yeah. The context here is a big boom in the industry, in the ’90s and early 2000s, especially as the payment changed in 2002, which reimbursed LTACs similar to hospitals, where they got bundled payments. Over the early 2000s, we saw an increasing use of LTACs, increasing number of facilities.

Anil: As a result, CMS has passed a couple of moratoriums. Then most recently, instituted the first patient criteria for reimbursement for LTACs. It doesn’t say that people can’t go to an LTAC, but you have to meet certain patient criteria to get full reimbursement on an LTAC. That started in 2016, slowly phasing in, and is fully implemented as of October 1st of this year.

Eric: That’s what, I always think LTAC; oh, somebody who we have difficulty weaning from a ventilator. Let’s send them to an LTAC. That is the minority group; I think 1 in 5 patients had, they were mechanically ventilated. A lot of those for a short period of time.

Eric: But the majority of patients, those weren’t those patients, right?

Anil: That’s right. One of the takeaways, I hope, for your listeners who aren’t familiar with LTACs is their role in post-acute care is a lot more beyond just chronically vented, prolonged mechanical ventilation. That’s definitely their ideal case, and what they’re best suited for, and where they originated from.

Anil: But people on mechanical ventilators in our data is only about 1 in 5. Meaning that 80% of people in an LTAC aren’t on a ventilator. But as I mentioned, the new criteria, one of the criteria is having either prolonged mechanical ventilation needs in an LTAC, or surviving an ICU stay in the hospital before coming to an LTAC. So we’ll probably see more in the future.

Alex: So the acuity of LTACs will go up.

Anil: It will go up.

Alex: Because right now, they’re taking people who are on long-term IV antibiotics, or wound debridement and treatment-

Anil: Exactly. I think it will go up, but not completely. One of the quirks of how I see user defined by CMS is also includes step-down floors and telemetry. So this isn’t like classical, what healthcare clinicians would think of as an ICU, necessarily.

Eric: Wow. So TCUs, they count.

Anil: They would count as an intermediate care unit for in the ICU definition by CMS.

Eric: Huh.

Anil: Still, I would think, moving forward, we’ll see an increasing burden of the chronically critically ill population in LTAC. But I don’t imagine that they’re going to be more than a third or half of the population.

Eric: I can’t think of any palliative care study, like a randomized controlled trial, of palliative care in LTACs or really any; can you think of any?

Alex: No. None.

Eric: Are there any palliative care interventions in LTACs? Any come to mind?

Anil: There’s actually, there’s just not a lot of research in LTACs in general.

Eric: Yeah.

Anil: Most of the work is on vent weaning and on the chronically critically ill: how many get off of a ventilator, what’s their survival. Very little research is on quality of life, palliative care, goals of care.

Alex: Hm.

Eric: Black box. Callout to our listeners. Let’s start figuring out this LTAC, how to actually get geriatrics or palliative care in these areas.

Alex: Anil wants to do that.

Anil: Yeah, no, something I’ve been increasingly interested and frustrated by, as this study was actually a prelude to a series of comparative effectiveness studies of just do LTACs offer better care and outcomes compared to the alternate setting; which is staying in a skilled nursing, or staying in the hospital or going to a skilled nursing facility?

Anil: This was our first study in just what happens with people, and it was just an eye opener for me. And it raised a lot of the questions you guys are bringing up. Is it the care people want? What’s their quality of life? What’s their burden of care?

Eric: What is the next step for you?

Anil: Looking at palliative care in the LTAC, writing a grant right now. Looking at, are people aware of their prognosis. We know that people have high mortality rates, and they spend a lot of time in the hospital. But people do survive. But what is their quality of life? Do they actually recover?

Anil: Then I think, ultimately, are they engaged in advanced care planning? This is what I would call tertiary prevention. My analogy to cardiovascular disease is, we think of advanced care planning and outpatient setting when people are well and healthy.

Anil: I as a hospitalist, I often see people what I would call secondary prevention, when they come in sick and we have to make decisions in the hospital, as well as future decisions. But this is like even after they survive a serious illness, and they go to an LTAC. But there’s still opportunity, I think, to engage people in advanced care planning.

Alex: Great.

Eric: That was awesome.

Alex: That was awesome.

Eric: I learned a ton about LTACs.

Alex: Me, too. I’m worried.

Eric: That they’re big in Texas. Do you like that-

Alex: Deep in the heart of Texas.

Anil: Deep in the heart of Texas.

Eric: Deep in the heart of Texas.

Eric: Anil, thank you very much.

Alex: Yeah, thank you.

Eric: Alex, would you mind; can we have a little bit more?

Alex: All right.

Eric: Deep in the heart of Texas?

Alex: (singing).

Eric: (singing).

Anil: (singing).

Eric: Whew!

Alex: Yee-haw!

Eric: That’s fabulous. Anil, big, big thank you for teaching me a little bit about LTACs. And a big thank you to all of our listeners out there.

Eric: If you have a moment, please, we would really appreciate; our hundredth episode is coming up. If you can take a moment and call our listener line at 929-GERI-PAL; that’s 929-GERI-PAL; and just leave a little blurb about one of your favorite episodes, or something else you liked about our podcast.

Eric: Thank you everyone.

Alex: Thanks. Bye.

Anil: Thanks for having me.