Providing palliative care to patients in their homes has been an irreplaceable experience that helped me refocus on the humanity and complexity of my patients’ lives. It helped me understand that there are deep underpinnings to why and how patients make difficult decisions about what treatments they want, where they get care, and what help and advice they are willing to accept.

Having caught a glimpse of the value of home-based palliative care (HBPC) and seeing how it could be a lifeline to functionally debilitated patients, I wondered why I had not heard more about HBPC programs during residency, especially given the robust evidence base for HBPC.1,2 I wondered whether these types of programs were accessible to most patients and what challenges existed to running and expanding these programs.

These questions ultimately led me to talk with a few leaders of HBPC programs around the Bay Area and California during an elective on HBPC. My goal was to get a sense of the practice of HBPC in my local area, understand the models being used to deliver HBPC, and learn about the challenges for expanding HBPC.

Overall, I learned that there is a lot of heterogeneity in the field. From programs with less than 10 patients to programs that have enrolled more than 1000 patients, HBPC is still in its nascent stages. Despite the many difference in the programs, the challenges they face were similar and worth reflecting on in the hope of acknowledging the hurdles for the next generation of palliative care providers to overcome.

1.) Finding and Keeping Clinicians

Several programs I spoke to described difficulty recruiting and retaining clinicians. Given the relative paucity of HBPC programs, few training programs offer mentored experiences providing palliative care in patients’ homes outside of hospice, and thus, physicians may have less comfort with providing palliative care without the support of a clinic or hospital structure. Also, in the Bay Area, where the cost of living is remarkably high, finding clinicians with palliative care training who are willing to live in the area is difficult.

Multiple program leaders described that providing palliative care for patients with evolving and often ambiguous goals of care can be especially taxing for providers. Even for providers who come from a hospice background, the change in mentality from exclusive comfort-focused care to a more fluid balance of risks and benefits and highly individualized treatment plans adds a layer of complexity and emotional weight that can take a toll over time. Navigating this space requires a high degree of comfort with uncertainty and ability to adapt from one patient to the next.

In addition to the strain of patients’ evolving goals of care, program directors described high rates of burnout with several programs expressing concerns about providers experiencing social isolation while providing HBPC. They described that clinicians may be part of a very small team and given that much of the work is done on the road and by a single provider for any given visit, most providers are separated from other team members for much of the week. This isolation prevents some of the important in-the-moment debriefing that can help clinicians sustain their practice. These anecdotal comments are supported by studies documenting rates of burnout among palliative care providers as high as 62%, with home care associated with higher rates of burnout compared to other palliative care contexts.3,4 These rates of burnout threaten not just HBPC but the entire palliative care workforce.5

2.) Finding the “Right” Patients

Multiple programs described the challenge of finding patients who are the “right fit” for the program. Mismatches seemed to come from many directions. A common theme was difficulty enrolling patients who were the “right level of sick” for the program. While some programs described having patients who were healthier, living longer, and having more stable goals of care than anticipated, other programs enrolled patients whose functional decline and social needs pushed against the resources available to meet these needs. These challenges were especially notable and problematic in smaller HBPC teams. Defining the role of the HBPC team and distinguishing primary care and palliative care needs for homebound patients also emerged as a common challenge for developing programs.

Even when using automated methods or algorithms to help find the right patients, programs enrolling patients based on pre-determined diagnoses, utilization, or costs described that these methods still identified patients either too early or too late in their disease trajectories to make meaningful impact on outcomes.

Matching the patient population to meet the expectations of payors or other organizations supporting the program was another stress point. Some programs described being unsure of how to best select a population for whom patient preferences, clinical care, and desired outcomes of the health system or insurer would be well-aligned. For example, if a program enrolled patients not frequently hospitalized or frequently seeking care in the ED, it is difficult to demonstrate ongoing value from decreased utilization.

3.) Paying for the Program

Similar to the findings of a study conducted by the Center to Advance Palliative Care (CAPC), financial stressors were a major concern across nearly all programs regardless of size.6 There is an incredible degree of heterogeneity in payment models ranging from philanthropic support, fee-for-service, shared savings, and per-member-per-month models, each with their own pros and cons.

Regardless of how the program is reimbursed, having a nurse, nurse practitioner, or a physician visit a patient in their home is an expensive endeavor. Figuring out how to optimize this was critical for many programs’ survival. Programs based on a fee-for-service model had to rely on nurse practitioner and physician visits in order to bill for their services, and there was much effort put into co-locating visits and minimizing the amount of “windshield” time for providers.

Programs paid on a “per member per month” model had more flexibility in which providers went to see their patients, but also struggle to find optimal ratios between providers and patients and finding the right amount of “touches” for each patient in a given timeframe. Several programs are beginning to use video visits as a way to extend care between in-person visits, minimize windshield time, and address urgent concerns that do not require an in-person evaluation in a timely manner while also reducing costs.7

4.) Scaling the Program

Challenges for growing programs came from both practical and theoretical concerns. On the practical side, there was a persistent tension between supply and demand. For some the theory of “if you build it, they will come” guided their teams to build robust interdisciplinary teams that then worked on filling the team’s capacity with patients. Other teams found themselves stretched thin and in need of expanding capacity to meet the demand that they took on while less well resourced. Regardless of which end programs find themselves, growth is challenging and there is rarely perfect harmony between the palliative care needs of a community and the capacity to meet that need.

Outside of practical concerns, some programs discussed concerns that growing larger could mean a loss of a patient-centered and human connection focus of the program. Whether this was a personal touch from a small team or a larger ethos of how palliative care should be provided, concerns about growth were common but often balanced with a recognition that there is ongoing unmet need in the community.

Next Steps:

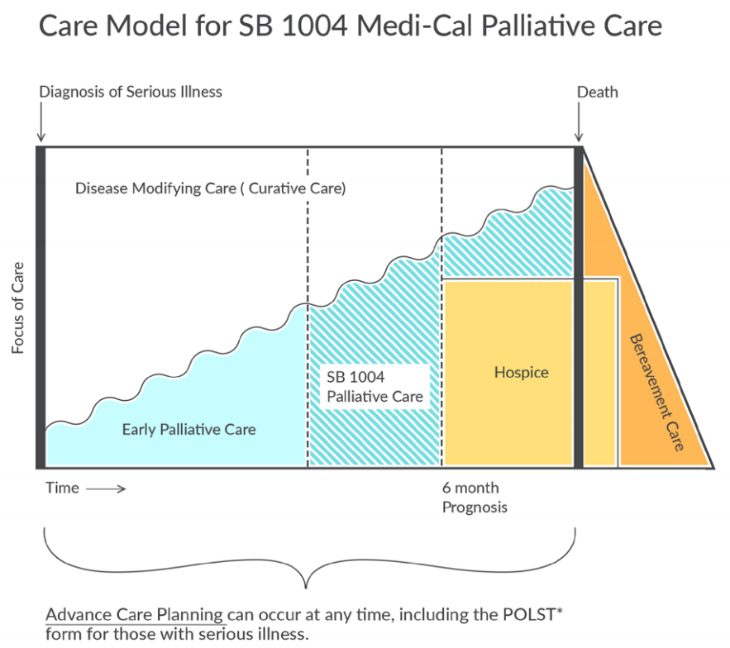

Despite these many challenges to sustaining and growing HBPC, there is progress in supporting this work. In California, the passage of Senate Bill 1004 (SB1004) expanded the ability for providers and health systems to get reimbursed for palliative care patients under Medi-Cal, our state Medicaid program. Some programs have used this funding opportunity to start HBPC programs. Funding models through SB1004 are diverse and include enhanced fee-for-service, per-member-per-month, and shared savings contracts, allowing enhanced reimbursement for palliative care to fit into many different systems.

As a palliative care fellow, these incremental changes are exciting stepping stones that I see as opportunity to continue refining and expanding access to palliative care services.

Grant M. Smith, MD

Clinical Assistant Professor at Stanford University School of Medicine – Primary Care and Population Health

References:

1.Gomes B, Calanzani N, Curiale V, McCrone P, Higginson IJ. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of home palliative care services for adults with advanced illness and their caregivers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013:CD007760.

2.Rabow M, Kvale E, Barbour L, et al. Moving upstream: a review of the evidence of the impact of outpatient palliative care. J Palliat Med 2013;16:1540-9.

3.Kamal AH, Bull JH, Wolf SP, et al. Prevalence and Predictors of Burnout Among Hospice and Palliative Care Clinicians in the U.S. J Pain Symptom Manage 2016;51:690-6.

4.Parola V, Coelho A, Cardoso D, Sandgren A, Apostolo J. Prevalence of burnout in health professionals working in palliative care: a systematic review. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep 2017;15:1905-33.

5.Kamal AH, Wolf SP, Troy J, et al. Policy Changes Key To Promoting Sustainability And Growth Of The Specialty Palliative Care Workforce. Health Aff (Millwood) 2019;38:910-8.

6.Bowman BA, Twohig JS, Meier DE. Overcoming Barriers to Growth in Home-Based Palliative Care. J Palliat Med 2018.

7.Calton BA, Rabow MW, Branagan L, et al. Top Ten Tips Palliative Care Clinicians Should Know About Telepalliative Care. J Palliat Med 2019.