On June 12, Betty Jean Collins of Warsaw, Missouri, executed a Durable Power of Attorney for Health Care Choices (DPOA-HC) and Health Care Directive appointing Tina Shoemaker (Collins’ grand-niece) as her health care agent. On June 16, 2012, Betty was involved in an automobile accident near Lincoln, Missouri, and was pronounced dead at the scene. What happened after that is absolutely fascinating, and should make all of us look at our state laws on who has the right of disposition of a loved ones body.

Collins’ advance directive stated that her DPOA became effective only after one physician certified that she was incapacitated and unable to make and communicate health care choices. It further indicated that her health care agent would carry out Collins’s wishes “regarding autopsy and organ donation, and what should be done with [her] body.”

Shoemaker, the health care agent named in the DPOA form, wanted Collins’s body cremated. Collins’s daughters, who would have had the power to dispose of Collins’s remains in the absence of an effective DPOA, wanted her to be buried in a family burial plot and motioned for a temporary restraining order to stop cremation. Long story made short, the matter was taken up by the Probate Court and then taken up by the Missouri Court of Appeals.

I suggest you read all of the arguments in the Appeals Court decision, but the gist is as follows: the daughters argued that the DPOA never became effective, because it “sprung” into effectiveness only upon a physician’s declaration of Collins’s incapacity. To put it in another way:

Because Collins had never become incapacitated before her death and because no physician had ever certified her as incapacitated, the health care agent never became Collins’s attorney in fact under the DPOA, so Shoemaker never had the rights to the disposition of the remains.

Shoemaker, the health care agent assigned in the DPOA form, agreed that Collins was never certified as incapacitated by a physician but argued (and I love this) “that death conclusively establishes incapacity sufficiently that no physician certification should be required.” They further argued the physician certification requirement was only meant to apply to the powers related to health care decisions during life and not to the right to dispose of remains (which most people probably think when they sign a DPOA form).

The appeals court took the position that the clear, unambiguous language of the DPOA executed by Collins expressly provides that none of its provisions become effective until the physician certification requirement is satisfied (springs into effect). So in the end, the DPOA was ruled not effective, and Shoemaker had no right to the remains.

So, from my non-lawyer perspective, it seems, at least how Missouri’s laws are written, if you want your DPOA to be making burial decisions for you, you should indicate in your DPOA that it is immediately effective, as opposed to “springing” upon incapacity.

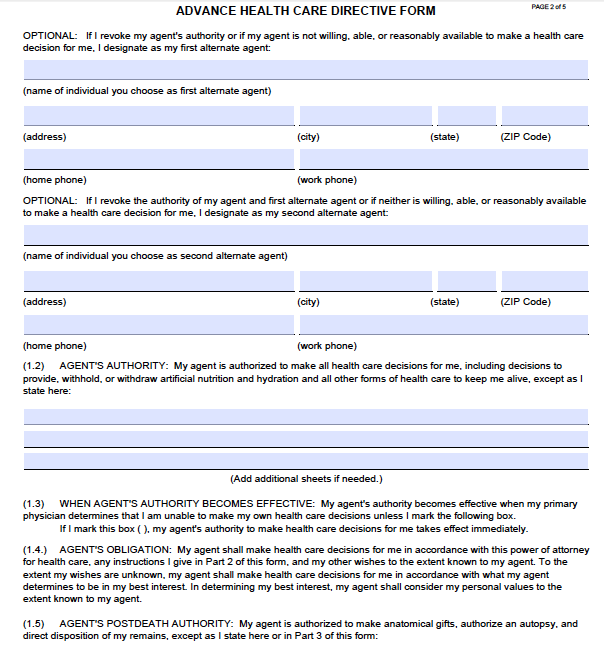

I’ve asked my legal counsel (my wife) if this same issue would come up in California. Her quick response is that “incapacity,” and certification thereof, are not the requisite conditions in the California statutory form (though in the Probate Code provisions governing custom made forms, incapacity is mentioned as the override-able default). The statutory form simply says: “If my primary physician finds that I cannot make my own health care decisions.” She admits that “incapacity” (living, presumably, but legally incompetent to make decisions) might have been what the California drafters meant, but likely in an effort to make the form more easily understandable, its “clear, unambiguous” language doesn’t include the word “incapacity,” or, maybe, its legal implications. All of that notwithstanding the fact that one could still argue that a dead person is actually incapacitated.

I’ve asked my legal counsel (my wife) if this same issue would come up in California. Her quick response is that “incapacity,” and certification thereof, are not the requisite conditions in the California statutory form (though in the Probate Code provisions governing custom made forms, incapacity is mentioned as the override-able default). The statutory form simply says: “If my primary physician finds that I cannot make my own health care decisions.” She admits that “incapacity” (living, presumably, but legally incompetent to make decisions) might have been what the California drafters meant, but likely in an effort to make the form more easily understandable, its “clear, unambiguous” language doesn’t include the word “incapacity,” or, maybe, its legal implications. All of that notwithstanding the fact that one could still argue that a dead person is actually incapacitated.

So it sounds like the stars aligned to make a perfect storm in this case, but lets just take a second to imagine what would happen in your state if this same scenario occurred and a DPOA didn’t spring into effect before a patient died? Who would have the rights over the remains? Would a physician need to certify incapacity? If so, what happens if a patient dies before that occurs, like in this case?

by: Eric Widera (@ewidera)

Note: If you are worried about your family fighting about this or are clear on what you would want to happen to your remains, give specific instructions about your preferences in an Advance Directive and in a Will (and anywhere else you can think of).