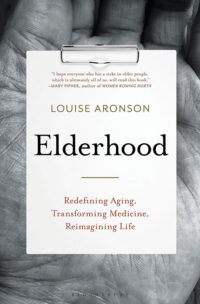

In this week’s podcast we talk with Louise Aronson MD, MFA, Professor of Geriatrics at UCSF about her new book Elderhood, available for purchase now for delivery on the release date June 11th.

We are one of the first to interview Louise, as she has interviews scheduled with other lesser media outlets to follow (CBS This Morning and Fresh Air with Terry… somebody).

This book is tremendously rich, covering a history of aging/geriatrics, Louise’s own journey as a geriatrician facing burnout, aging and death of family of Louise’s members, insightful stories of patients, and more.

We focus therefore on the 3 main things we think our listeners and readers will be interested in.

First – why the word “Elder” and “Elderhood” when JAGS/AGS and others recently decided that the preferred terminology was “older adult”?

Second – Robert Butler coined the term ageism in 1969 – where do we see ageism in contemporary writing/thinking? We focus on Louise’s delectable takedown of Ezekiel Emanuel’s Atlantic Article “Why I hope to Die at 75”

Third- Louise’s throws down the guantlet to the field of geriatrics. She argues that we have held too narrow a view of ourselves as clinicians for the oldest old and frailest frail. Instead, we should expand our vision of the field to include all older adults – including healthy 60/70 year olds & healthy aging – and become the default clinicians for all people entering life’s last stage.

Elderhood is a terrific read, and you are listeners/readers will all be inspired by the ideas, moved by the stories (you will identify with them), and challenged to re-imagine our clinical practice.

(apologies – I had a cold so sort of struggle through the singing, far different from my usual perfect rendition!)

Eric: Welcome to the GeriPal podcast, this is Eric Widera.

Alex: This is Alex Smith.

Eric: And Alex, we have a guest in our studio office today — which is just my office so this isn’t as fancy as some of the places where our guests will be over the next few weeks — Louise Aronson, who is professor of medicine in division of geriatrics here at UCSF and an author. We’re going to talk about her second book today titled Elderhood. Welcome to the GeriPal podcast, Louise.

Louise: Thank you. It’s an honor to be here. I often listen to you two while driving.

Eric: So before we get into the book and some of the aspects of it, we always ask our guests, do you have a song for Alex to sing?

Louise: Well, this was actually the hardest decision I had to make about this interview, but I’m going to go for Grandma’s Hands by Bill Withers.

Alex: (singing)

Eric: Nice. Why did you pick that song?

Louise: I actually had a hard time picking the song because there are so many, but a lot of them are pretty negative and that one really talks about grandma just as a person and women in particular will talk about aging hands as a bad thing, and so I loved that Bill Withers talked about them as a symbol for all she meant to him and all her power in their family and community.

Eric: That’s great, I mean just having read your book (which I got as a PDF)…wait, before we talk specifics about your book, when can people actually start purchasing your book? When is it out there?

Louise: Well, so you can purchase it right now anywhere, any bookstores, Amazon, Barnes and Noble, anything online and if you buy it now, it will arrive at your house on June 11th which is publication day.

Eric: And as you’re reading the book, there’s a lot about the kind of the words we use about some of the biases that we have about ageism, I’m hoping we have time to talk at least about some of these aspects. Maybe we can start off with just the title. How did you come up with the title?

Louise: Well I actually started with Oldhood as the title. That was my working title for a couple of years and-

Eric: Sounds like a place in Connecticut.

Louise: Yeah, Oldhood, yeah, it’s true. Just up the highway. So I wanted to do Oldhood because I was really thinking about it in terms of a long and meaningful phase of life, no different than childhood or adulthood. The longevity dividend basically pays out in our older years and so I wanted to have a phase, an analog to childhood and adulthood and I wanted to use old because we act like that’s a bad word instead of what it is, which is a neutral descriptive term for something that’s been around a while. But when I used that term in an article in the New York Times, a very wise reader sent me a note, many people sent notes saying, “I’m not old,” and exactly proving my point, but this smart woman said, “Well, it doesn’t work grammatically because if you have childhood, you have child, adulthood you have adult. If you have oldhood, you have an old, what is an old?” Right? So then I realized I had to go with Elderhood and elder.

Alex: And there’s a story here too about the meaning of the word old and the meaning of the word elder.

Louise: Yeah. So early on in the book, I tell a story about a geriatrician at UC Berkeley called Guy Micco, who for years (he’s recently retired) did this exercise with his students where he would write the word old on the board and say, “You’ve got one minute, write every word that jumps into your mind, don’t filter, just write.” And after a minute he’d say, “Stop.” And then he’d write the word elder on the board and have them do the exact same thing. And what he found consistently over years, and not just with medical students, mind you, but with his friends who were themselves, no spring chickens exactly at that point, was that everybody had negatives about old, wrinkled, sad, frail, etcetera, etcetera, and when it came to elder, it was wise, powerful, wealthy, important. So if you look up these two words in the dictionary, the definitions are basically identical. So all of that is cultural overlay and biases that we indulge as individuals and as a society.

Eric: Wait a second. So both me and Alex, we are part of the Journal of the American Geriatric Society and part of AGS, I thought I was supposed to be using older adults when I referred to that specific population and elder is out.

Louise: Right. So it’s important to know the origins of that preference. So that is societies and the American Medical Association has the same sort of guidelines for that when you’re discussing someone who’s over age say 60 or 70, you’re supposed to use the terminology older adult. And that’s based on work, everything from Ina Jaffe at NPR to the FrameWorks Institute, which sort of talked about how do we talk about aging as a society. And they all found that the preferred terminology basically no one liked any words for being old, but if they had to pick one, what they wanted was older adult. So I too initially began using that and substituting it. And then I realized in writing this book that that too was pandering to the very prejudice that makes people dislike words like old, elder or really any words for being old. And what they dislike about them is that they’re associated with being old.

Louise: And so they inadvertently reinforce the prejudice. Older just means more than, right? So I am an older adult than you guys, even though I’m not an older adult yet. It’s just a relative term. And then perhaps most importantly you get the word adult in there. And that’s because we consider adults the most powerful phase of life. And so it’s basically negating your very identity and by doing that you actually make it more onerous and more negative. Instead of saying, “Hey, I’m 70 it’s great.” I mean if you look at happiness curves, people at age 70 are way happier than people at age 40 or 50. Anxiety goes down, life satisfaction goes up, happiness goes up. So instead of saying 70 is the new 50 as if 70 never has anything to recommend it, 50 would do well actually to be the new 70 because people in their 70s are happier. Anyway, I decided we were pandering and that we should stop.

Eric: Didn’t that also have something to do with the us versus them mentality like older adult is… it acknowledges that yes, we all will become older adults versus elderly, if I’m remembering this correctly, like there’s this other group, they’re the elderly and I thought older adults had something to do about that, that reframing of this is something that we will all experience and be a part of. I could be just making this up in my head right now.

Louise: No, and I think that’s another argument for it potentially, although really what seems to be going on is people wanting to be seen still as adults instead of as elders. But if you were to line up an eight year old, a 48 year old and an 88 year old, there’s not going to be any question that these are different animals in terms of what their bodies do, how they spend their time, how they feel, what their priorities are, how we’re going to deal with them medically, they’re just different. And yes, it’s all us, but it can also be all us if we know that unless you die early, you’re a kid, you’re an adult and you’re an elder and each phase has multiple subgenerations and substages and great pleasures and great difficulties.

Louise: One of the problems is we tell all the bad stories about old age and none of the good ones. Basically we don’t take an evidenced based approach to the facts of old age within medicine or in society, and who wants to be a teenager again or the sandwich generation with a full time job and kids and older parents. There are lots of stressors and difficult things along the way and I think we just need to be starting to tell the real stories and making it okay to be old and you start that by calling it what it is.

Alex: Yeah. I’d like to move on to talk about a related topic which is this term ageism coined by Robert Butler who spoke very eloquently about the reasons that this phase of life has such negative connotations in our society. But before I do, I just want to note for our listeners who are mostly people interested in gerontology, geriatrics, practicing clinicians, palliative care clinicians, this book is tremendous and you should go out and get this book. It is perfect for everybody who listens to this podcast or reads the transcript. It is filled with stories which we probably won’t have time to get to today and pushes us in both geriatrics and palliative care (we’ll get to a little bit of this today) to rethink and push us in a number of different areas to expand our focus or to think differently about our own fields. But sort of continue the thread, I wonder if you could talk a little bit more about what is ageism and what is it about that phase of life that has such negative connotations in our society?

Louise: What’s really interesting it’s not just our society. So part of what I did for this book was read the sort of the history of old ages across as many cultures as I could access, which was mostly Western cultures admittedly since I only read Western languages. But traditionally in different societies at different points of time people have either revered elders and given them a special and prominent place or disparaged them, and sometimes both. When you were the young-old or the go-go or go-slow sorts of older adults, you were revered and included in the community and once you became really frail, then you were sort of left. The initial hospitals were really sort of poor houses for abandoned old people, very poor and very old people, that was how they started.

Louise: So it’s not really new and I think it’s a few things, it’s that other thing we were talking about before and old is always other when we start life, right? Because we’ve never been there before, by the time you get there, you can’t go back, so you don’t know. And I think it’s also self perpetuating that because we see life as this getting stronger and more powerful, when we start losing things, we interpret it partly I think in the modern era it’s because we think of human beings as machines since the industrial revolution…it’s about function and efficiency and we don’t value other things so much and we do in our individual lives, but as a culture we really don’t. So it’s just easier to put people aside or say, “Well they’re slow,” or, “They’re different.” I mean ageism isn’t the only ism, there’s every ism possible, it’s what human beings do, we have us and we have other. The weird thing about this one is that if you stay alive, you will become this other so it’s all the more self-defeating, not that there’s ever an excuse for it, but I mean you’re basically hurting your future self as well as your current older relatives every time you say something ageist, or do something ageist or support these policies that are so ageist.

Alex: Right. And there are example after example after example in here in this book of people unwittingly, inadvertently even Atul Gawande in his opening line of his the Being Mortal book and Zeke Emanuel who said this, he wasn’t subtle about it, right? When he wrote about this issue. After age 75, to summarize, he’s opposed to euthanasia, but he also doesn’t want to continue treatments that are likely to prolong his life because he views it as a diminishment of his abilities that is not compatible with who he sees himself being, productive, thoughtful person.

Eric: How old is Zeke right now?

Alex: I don’t know.

Louise: Later 50s maybe, I feel like I looked it up.

Alex: Something like that. But you sort of do a terrific take down of this perspective, I wonder if you could go into that a little bit.

Louise: Well, I think it’s probably not coincidence that he has been a very successful white male. So there is that harder they fall phenomenon, which has been studied by sociologists and anthropologists.

Alex: I just want to make sure that everybody knows Zeke Emanuel because some people may not know him. Right, he’s a bioethicist, he’s a professor at the University of Pennsylvania, I think chair of their ethics department, his brother was mayor of Chicago and formerly worked in the Obama administration and he’s one of the leading sort of thought leaders in the ethics and healthcare space.

Louise: Right, and the part I responded to was first an article in the Atlantic and then an interview on the New Yorker podcast with David Remnick. So I think a few things, he defines himself clearly by his power and abilities and I felt like he didn’t take into consideration the other demographic factors that enabled him to become the person he was. And that in saying lives that aren’t as intellectually, because he wasn’t just speaking for himself, he literally makes comments that if you’re a grandmother and you’re looking forward to seeing your grandkids and being in your garden and watching some TV, your life is essentially not worth living. And I felt like he was both judging in a way that he doesn’t really have a right to judge if somebody else is happy, who is he to judge?

Louise: But he also seemed to have no understanding of the larger social context that partly, I’m not saying he didn’t work hard or he isn’t brilliant, right? But the larger social context that gave him advantages, often invisible advantages all along the way that enabled him to get to that height and to devalue people who are differently abled or who are born with darker skin in this country and we know how insidious and horrible that is for people’s opportunities, it’s not a complete deal killer, but it makes a colossal difference. And I just felt like he was shortchanging all of those really important factors. There’s just one other thing which is that he also takes a sort of not age informed approach to old age because he picks a number and as we in geriatrics and palliative care all know it’s not about the number.

Eric: And it’s a very classic number 75. I’ve always wondered where did that number come from? Whether it be like stopping colonoscopy screenings, was there one pivotal prevention study that use 75 and then everybody else jumped on it? It’s not connected to anything else, right? Alex, you know where 75 came from?

Alex: No.

Eric: No, but it’s repeated over and over again whether it be from old guidelines around colonoscopies or mammograms or-

Louise: Yeah. And it’s really different from the 65 because you can find 65 and 70 in history but not so much 75.

Eric: 75 yeah, right?

Louise: And I wonder if it’s because it’s not in that 60 to 70 range where we consider, okay, most people are doing still well by adult standards, which already I disagree with, we judge if you applied adult standards to your toddler, they would have physical, emotional and intellectual deficits that were very significant. So we shouldn’t do to elders what we don’t do to other people. And then everybody 80 is considered as old, so I bet they just split the difference…random.

Alex: I thought you made a terrific point here as well about there being a gender story here, it also discounts the value of society and individualize of the same sorts of work that often go unpaid or underpaid, so-called women’s work, most particularly caregiving and volunteering of all sorts. A quarter of America’s 40 million unpaid caregivers are themselves over age 75 and most are women, yeah, terrific point. And then you bring up a wonderful counterexample, which is Anne Fadiman’s father, who… I’ve read “The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down,” so I’m more familiar with her than I am with her father, although as you noted in our conversation before we started, many older adults will remember her father. I wonder if you could tell us that story about him.

Louise: So Clifton Fadiman was one of the most famous men of his generation. He had a radio show that I guess everybody tuned into on Sundays and he was then the editor I think, or maybe that was Anne, anyway, he was an intellectual writer, one or both of them were at the American Scholar. So in his 90s, if I recall correctly, he had an eye condition that rendered him essentially blind. And this was a man who loved to read and write, I mean his whole identity aside from wine and the book is called The Wine Lovers Daughter, but wine and family, but beyond those, it was about reading and writing and suddenly he couldn’t see. And he says to his daughter that he just assume die and she says, “Let’s give it a few months and we’ll discuss it again. I’m not putting you off, but this just happened. Let’s give it some time.” And so they end up signing him up for a visual aid class basically, coping with being newly blind. And he goes, and they stay home and they wait and he comes back after a full day and they say, “How was it?” And he breaks into this grin and he says, “That was maybe the most interesting day of my whole life.” And he ended up listening to books on tape and hearing things and living many years longer and very, very happily.

Alex: Yeah. So this idea was, I think there are so many interesting things about this story. One is that our preconceived notions of what it’s like to be old, to be an elder, to be disabled, to have impaired function, visual, sensory, physical, cognitive. We vastly under appreciate our ability to adapt to adverse circumstances and discover new ways of making life interesting and finding meaning from life. And that’s one of the pieces that stuck out for me from that story.

Louise: Well it also illustrates one of the huge points of the book, which is a lot of the stuff that we blame on age, whether in healthcare or in society are things that we do. Not everybody could have gone to a class on blindness or could have afforded somebody to come take dictation or all those other things, and that was part of why I paired those two men because they were similar. But we could make that easier and then we could see that old age was pleasant even though you had to change and adapt and then people wouldn’t be so scared and then we could use the word “old.” That is a very simplistic rundown but basically that’s the general concept.

Eric: Yeah, I think this is the particular challenge that a lot of what we do. We have these goals of care conversations with our patients and we’re trying to predict future states and what their wishes would be and whether or not from our conversation from Zeke or how we adapt to new situations, does it call it a question at all the concept of advanced care planning because we are so adaptive that we imagine a future state that is worse than it actually will be because we may adapt to it?

Alex: This is a terrific point, Eric. Jodi Halpern, who’s another professor at UC Berkeley and a psychiatrist has written about this, affective forecasting. We think that life is going to be terrible if X, Y and Z circumstances, but we’re not actually very good at predicting what life will be like under X, Y, and Z circumstance.

Louise: Not only that, and I quote this in the book too, but Becca Levy a psychologist, researcher at Yale has really good data, like 20 years of data showing that the more you internalize those negatives, the more you internalize ageism, the worse your health and life outcomes and that’s everything from how well you recover after a surgery to your chances of heart disease and death from heart disease being years earlier to having Alzheimer’s markers in your spinal fluid. It makes a big difference.

Alex: So I think we need to get into this. We have to get to this part of the book because many of our audience listeners are practicing geriatricians and you argue for what I’d call a sea change in geriatrics that geriatrics has too often defined themselves as focusing on the most complex, the frailest, frail, the oldest old and that narrowing of our scope, it does a disservice to the field and we need to expand our vision to include all older adults, all elders and focus on healthy aging, prevention, etcetera, not just this particular subtype. I wonder if you could say more about that challenge to the field.

Louise: Well, my whole career, so I first got interested in geriatrics almost 25 years ago now and the entire time and then go back before that as well, people have been saying, “Well there’s so few of us we have to focus on the oldest old.” And that’s been great for the oldest old, the minority of oldest old who are able to see a geriatrician. But yes, you can say it doesn’t really matter which field takes care of people as long as they’re getting good care. But here’s what we know, they’re not getting good care, we’re not making more geriatricians than we were, and even the old frail people, there are nowhere near enough geriatricians for them. So to keep doing what we’ve been doing when it has clearly failed over a period of decades isn’t right. Now, I don’t know if my suggestion is right, but I went back to where the word geriatrics came from, which was in 1909, Ignatz Nascher was speaking to Abraham Jacobi, I think was his name, the famous pediatrician at the time, and coined the name geriatrics to be an analog for pediatrics.

Louise: Well, for pediatrics, people are trained in neonates, infants, toddlers, tweens, teens, young adults, right? We should be trained in all of old age. Otherwise we need to stop complaining that people see us as small and no one wants to join geriatrics. Let’s make it about all those phases of old age. There’s lots of cool aging science. There are tens of thousands way more people in the anti-aging and basic aging and healthy aging spaces than there are in geriatrics. So either we take care of all old people, we are doctors for old people or we are a small field and we need to stop whining.

Alex: Eric, you’re a fellowship director for geriatrics. You are involved in the geriatrics leadership nationally. How do you feel about this proposal?

Eric: Yeah, I do feel like in the last several years there feels like there is a change in the direction, I actually feel like there’s more uptake of geriatrics from healthcare organizations. It feels like just recently there may be more interest in geriatrics so I do worry a little bit about like every other year we talk about redefining geriatrics, it’s the same thing with palliative care like what should we call palliative care? Who should we target? There’s not enough of us. And I think it’s true for probably every specialty out there, there’s not enough nephrologists, there’s not enough… and this is just something doctors like to complain about and you see it with every-

Louise: Except for the disproportion between numbers of specialists and target population is far greater for geriatrics than for anything else.

Eric: Yeah. Although endocrine, nephrology, they’re facing very similar shortages they have difficulty attracting new people coming into the field and I think it’s true for any cognitive specialty, you just don’t get paid as much and that matters.

Alex: Well, what would this be like? Imagine a world in which geriatricians, were the pediatricians of older adults. When you thought about taking somebody who is like 65 or 70 years old and relatively healthy to a doctor, you think about taking them to a geriatrician. Right now you generally don’t do that unless they have functional…it’s not just age, but-

Eric: And they don’t consider themselves old so they would not go…I think you talk about this in your book too right?

Louise: But it’s self-perpetuating, right? We define it as the very oldest old, right? We’re doing with geriatrics exactly what we’ve done with the word old is we’ve made it really small and stage when if you’re going to use it accurately, both historically in terms of the dictionary definition and in terms of how we change physiologically, it’s a much bigger thing. And actually in my new clinic, which incorporates all of this, my youngest patient is 62 and yes I did a little double take the first time I saw that because she’s not that much older than I am, but she’s thinking about aging and what I do with her is really different from what I do with a 72 year old or 102 year old and I see them too. And it actually makes it fun, I mean the more varied the field is, the more people are attracted. And we also in coming in at the end, fall prey to what so much of American medicine does or medicine generally is we wait for people to get sick or to have problems and then we come in with our fancy technology and drugs to rescue them. If we started earlier, we could increase people’s health span and function spans by really helping them using our expertise on the aging body and aging lives and preferences to keep them healthier and more functional longer.

Eric: Yeah. I think the challenge is also around that value equation is where can geriatrics add the most value, not just for the individual, but given it’s a limited resource to healthcare organizations. And I think what we’re currently thinking is that value proposition is around frail, older adults. However, maybe we should be rethinking what it sounds like.

Louise: But so I would argue that if you look at the huge marketing literature and people get advanced degrees in this, or you look at how to raise money, the broader the goal, the more you get, right? So in saying we’re narrow, we keep ourselves small. So I think the value proposition should change. Also this one really isn’t working, it’s not serving older adults which is the most thing. But also if we say we’re all about old age, then it becomes something that’s more, excuse me, attractive to everyone from patients to clinicians to funders.

Eric: Do you have similar thoughts on where we should be going in palliative care?

Louise: Well, I think palliative care is actually doing a little better than geriatrics in this regard because it really thought about clearly how it’s going to articulate what it does in a way that people can listen and then working on the value proposition for health systems and we’re just getting there in geriatrics, but we’re a little bit behind palliative care there.

Alex: And in your book, in fact you say there is a war going on between aging and death, between… and in some sense between palliative care and geriatrics.

Louise: Yeah, I think it’s more the former than the latter, although, because we live in such an ageist society, do we have colleagues in palliative care who sometimes really disrespect geriatrics and will act like it’s irrelevant to what they do whereas if you really look at death curves, we know it starts going up in the 50s and by the 70s it’s looking pretty steep.

Louise: So but I think the bigger thing is really for the cultural imagination between aging and death and in this era of sort of rapid fire information and efficiency, in some ways death is more efficient, right? It has a finite end point. Whereas geriatrics, I mean now we have generations of older adults, one of the recent discussions that the American Geriatric Society was what happens when you start taking care of two generations in the same family as a geriatrician, which is happening to all of us more and more. So geriatrics is much bigger and involves far more primary care and we know what a tough sell that is. But I think in the public’s imagination, aging is really scary and death, oh, well, if you could make it comfortable, I guess I have to do that, so that’ll be okay.

Louise: And there is more of a romance to death than to aging currently. I also see that changing.

Alex: You see that changing?

Louise: Yeah, well, at least more attention to aging, which comes in a variety of ways. But I’ve been looking out for stuff on aging for years and I used to find something every six months and then it was every month and now I can’t keep up with all the reading I can do about aging every day, like who has time?

Alex: Right, and maybe this has to do with demographic shifts in the population.

Louise: Do you think? I think it could be.

Alex: Yeah, it could be.

Louise: Boomers aren’t having it.

Eric: If you talked to a lot of palliative care providers, including myself, part of the reason I went into palliative care and I’ve always had this fascination and interest with death and dying and from medical school and on and I always attended those kind of lectures and I don’t think that there’s that same, that fascination with aging that you’re seeing at least I don’t see it the same with med students. Even the aging interest groups don’t have that same, what’s the right word? Draw, I think.

Alex: Yeah. It’s like a mission. Ken Kavinsky likes to describe it as, it’s like the Kool-Aid. It’s like I am on a mission in palliative care and they have that sense of purpose and zeal and in aging and geriatrics we haven’t quite clearly articulated our vision such that people buy into it and are just sort of taken with that passion and zeal.

Louise: Well, I think that ties back to enlarging geriatrics, right? We’ve got three main phases of life, the third one we make harder and more fearsome than it needs to be. Isn’t geriatrics about making the third phase of life as long and meaningful and happy and healthy as it can be? That’s a pretty great thing, I mean, yes, a good death is good, but hopefully it’s pretty short and quick, right? Whereas we’re talking decades of life and one of the things I like to say is do I know enough palliative care to give you a good death? Yes, but more importantly, I know enough geriatrics to give you a good life.

Alex: That’s great. And there was a… I was looking for it, I couldn’t find it right now, a great quote from Robert Butler again about this issue of fascination with death and we sort of skip over this huge period that often precedes death that is older, aging and living in the old age.

Louise: Right. And that’s where palliative care is winning because if you look at a lot of health systems or other places, you’ll see, oh here’s pediatrics, here’s adults, here’s death. Oh, what happened in between? Oh we became invisible, we don’t matter. And that’s why we need elderhood because there are three phases whenever you’re talking about kids and adults or childhood and adulthood, you need to invoke the elders and elderhood as well.

Alex: And Louise Aronson by the way in this book talks about her evolution as a person, her own health and health of family members, aging family members, her own perspectives on aging, aging of her own body and changing perspective and her own clinical work and how she’s worked at house calls, ACE Units and now this new clinic, which is targeted more towards health and wellbeing and is… is it located in the Osher Center?

Louise: It’s in the Osher Center, but it’s health and wellbeing whether… like last week’s clinic, I had a person in her 100s who is mute from dementia and wheelchair bound, but I’m still working on her health and wellbeing. It’s not healthy aging like the dot com version of it.

Alex: What you call the clinic?

Louise: The clinic is called Integrative Aging.

Eric: Integrative Aging.

Alex: That’s good.

Louise: I mean it was the clinical site that would let me have this broader vision of geriatrics as something for everybody.

Eric: Well, there’s so many other topics that we could talk about in the book, but not to give away all the spoilers on this podcast, I really encourage everybody who’s listening to pick up one of these books. When’s it out again?

Louise: June 11th.

Eric: June 11th

Louise: You can order it now though.

Eric: Pre-order the book. I really love the historical aspects too. You really took a deep dive into the history.

Louise: It was fascinating, absolutely fascinating. So almost everything we think we’re doing now that’s novel, the way we’re doing it might be different, but none of it is new. Our species has been at this for Millennia.

Alex: Right, time is a wheel and history repeats itself.

Eric: Yeah. Well, maybe we can end off with a little bit more. What was the song entitled again?

Alex: Grandma’s hands by Bill Withers.

Eric: Grandma’s Hands.

Alex: (singing)

Alex: Thank you so much, Louise this is wonderful, a lot of fun.

Louise: Thank you for having me.

Alex: I really enjoyed this book, it’s terrific.

Eric: And thanks to all our listeners for joining us today. Pick up the book Elderhood, and we look forward to having you on our broadcast next week.

Alex: Bye folks.

Eric: Bye folks.