by: Alex Smith, @alexsmithMD

Alone in the room with your patient, you think you have control over what happens? You think that it’s you and the patient setting the terms and content of what tests and treatments are offered, negotiated, and agreed to?

Think again.

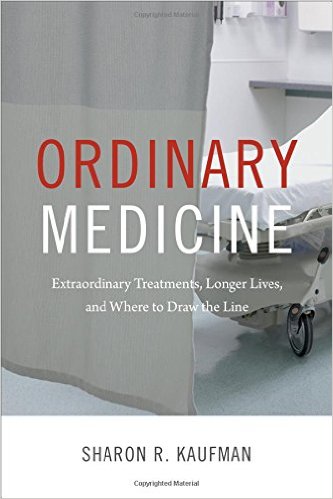

In a brilliant new book, Ordinary Medicine: Extraordinary Treatments, Longer Lives, and Where to Draw the Line, the medical anthropologist Sharon Kaufman illuminates the role of larger forces in shaping what is discussed in clinic examination rooms, at bedsides, and in consultation. We had the pleasure of hosting Sharon Kauffman for our fist ever UCSF Division of Geriatrics Book Club yesterday.

Her book took me back to my freshman Introductory Sociology Class at Michigan. I remember hearing about the “invisible hand” of larger social forces that, without our intention, guide our actions.

Here are two compelling examples from her book of how larger social forces are shaping conversations between patients and clinicians:

- The rise of the Medical Industrial Complex. In 1980, pharmaceutical and device funding accounted for 32% of medical research funding, now it’s 65%. That’s a huge shift. As we in medicine all pretty much bow down at the alter of Evidence Based Medicine, the evidence we rely on is increasingly set by industry, big pharma, and device manufacturers. This has played out, for example, in ever expanding criteria for Implantable Cardiac Defibrillators (ICDs). ICD’s are now being put into people in their 80s and 90s, into people who have never had a symptomatic arrhythmia, because doctors feel that if the evidence is there, they have to offer it.

- Once Medicare approves it, it immediately becomes standard of care. Doctors now feel that they have an obligation to address Medicare approved treatments. These forces are not just influencing doctors, who feel compelled to offer and discuss Medicare approved tests treatments they would not recommend, as Sharon Kaufman notes in her book. As we discussed in our book group, patients now search the internet and request these tests and treatments. I have an oncology friend who says, “My patients all want a the latest scan or genetic test. In most cases, it won’t change my management. I tell them that. They say, “Will my insurance pay for it? Then I want it.” Kaufman describes this as the “more is better” approach in medicine. My oncologist friend describes it as a patient approach to value-based health care: “I want all the tests and treatments my insurance will pay for.”

So you think you have control over what you talk about with a patient? Think again. You’re not alone with your patient in that exam room – there’s an invisible hand reaching in and guiding your conversation.

The hard part about these larger social forces is that it’s very hard to recognize them in your every day practice. It takes an outsider looking at the system with an anthropologists eyes to recognize what a strange system we work in, that the rules are rigged, and that health, well-being, and improved quality of life are hardly the goals and outcomes our health care system is designed to promote.