by: Alex Smith @AlexSmithMD

Wouldn’t it be great if we came up with a standardized approach to caring for hospitalized patients in the last two days of life? Think of it. Experts in hospice and palliative care could come to consensus on the best palliative care pathway for hospitalized patients nearing the end of life. Standardized assessment of distressing symptoms, the use of opioids, and other common medications used near the end of life. We could incentivize use of pathway, and improve care across the board. We should do it, right?

Well in the UK, they did it. It was widely adopted in the UK and throughout Europe. And now they’re retracting it.

The Liverpool Care Pathway was just that – an intervention designed to export the best of hospice and palliative medicine to non-palliative care clinicians caring for hospitalized patients in the UK. And now the government is scrapping it.

How did this happen? First, two critical must reads for more details. Stories in the media and medical literature documented serious concerns about the quality of care for patients dying under the Liverpool Care Pathway. An investigating review panel found serious issues with the implementation and dissemination of the pathway. The full report of the review panel can be found using this link.

The second source is a fantastic essay by palliative care pioneers Andy Billings and Susan Block on take away lessons from the failure of the pathway, published in the Journal of Palliative Medicine. Some of theirtake home points:

- Interventions should be evidence based. A recent Cochrane review concluded there was insufficient evidence for palliative care pathways for the dying.

- Interventions should be simple. The Liverpool Pathway had over 50 steps; it’s hard to implement such a complex pathway effectively.

- Interventions require sustained monitoring, support, and/or coaching. The early adopters are often “true believers” – later adopters not so much.

Here I will restrict my comments to two main take home issues.

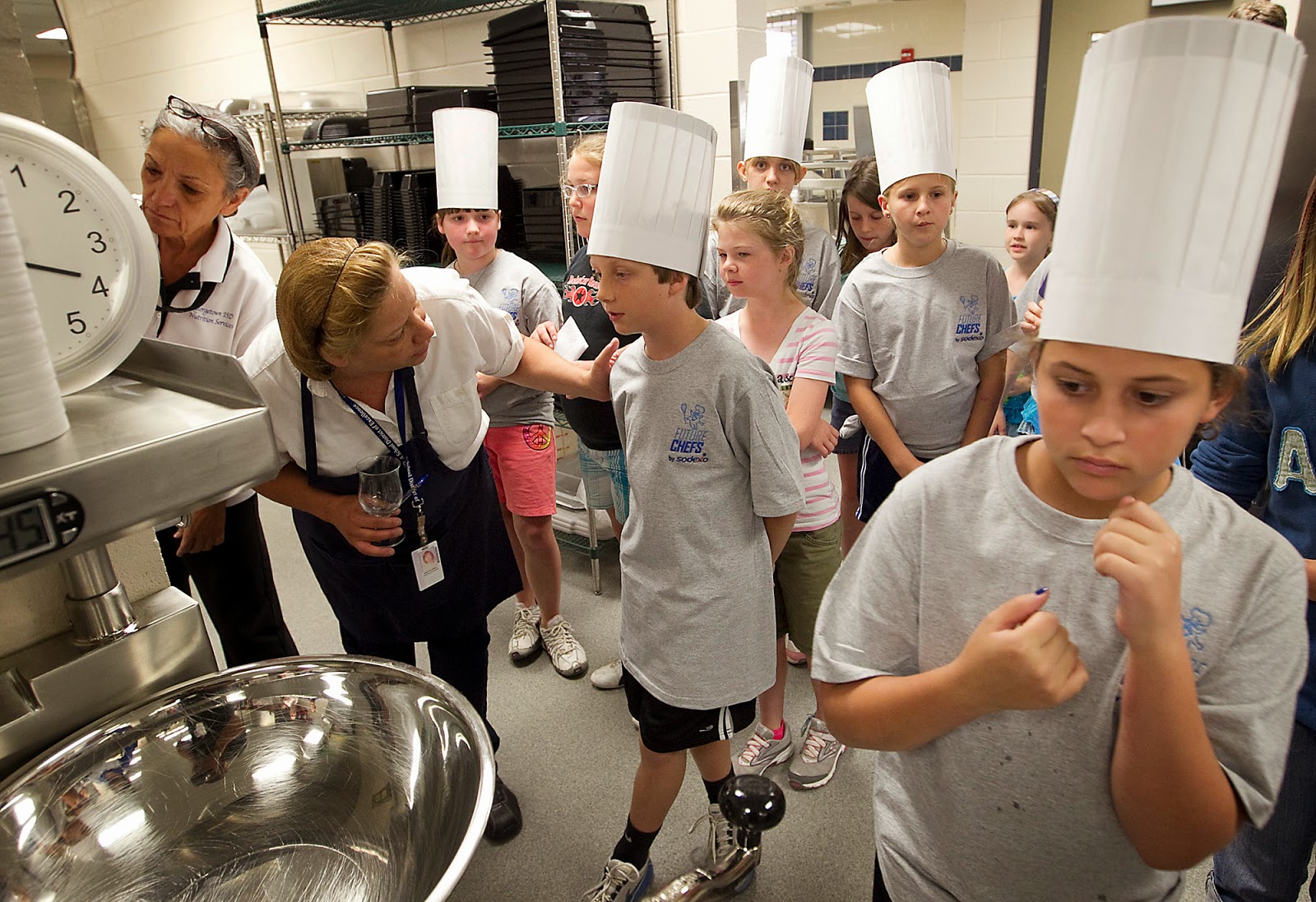

First, the “cook” issue. Tim Quill and Amy Abernathy wrote a compelling argument in NEJM for training all clinicians in basic primary care – everyone should be able to at least cook pasta. As we expand our horizons to train hospitalists, emergency providers and primary care clinicians in primary palliative care, we have to do so with a deep respect for our profession. We have selected palliative care because we have a deep sense of commitment to care for patients with serious illness. Ken Covinsky has observed that palliative care providers approach their work with “missionary zeal.” We are the true believers. We have all drunk the Kool-Aide. But the non-palliative care providers we train have not.

When I conducted focus groups with emergency medicine clinicians about incorporating palliative care into the emergency department, one physician said:

This is an overgeneralization, but I think that palliative care has a little bit of a negative connotation in the emergency department. If you think about people who go into emergency medicine, they want to sort of act and do, cure. When someone comes in and their status is DNR or comfort care, it is not necessarily seen as a priority or as a good thing. The first reaction is almost “Why are they here? Why are they bothering us? This is not an emergency.” “

As we train others, we have to be acutely attentive to the fact that those we train do not have the same internal incentives to provide outstanding palliative care for their patients. This is not to say that non-palliative care providers cannot do a great job of caring for patients with serious illness. Rather, it’s to say we need to work twice as hard and be twice as diligent in training others to do this work, monitoring their progress, and providing feedback.

Second, the “cookbook” issue. Those of us in palliative care have received some serious training. Palliative medicine physicians now must complete a one -year fellowship and pass board certification. Our specialty is not easily reducible to a formula. We attend to emotional, spiritual, and social concerns. We learn advanced communication techniques so we can walk with patients and caregivers through the tough, painful, sad experiences of serious illness that would send other clinicians running scared. This is not easy “anyone with a cookbook can do it” care.

We need to respect our profession and the complex work we undertake. We cannot reduce it to a cookbook. For this reason, I’m generally not in favor of “end-of-life” order sets. I’d rather tailor each decision to the clinical situation at hand.

To be sure, many palliative care concepts can and should be taught to primary care clinicians, hospitalists, cardiologists, etc. But we must do so with full awareness of the differences between our missions and the complexity of decision-making for patients with serious illness.

I’ll leave you with some painful experts from the Review Panel report on the Liverpool Care Pathway. Clearly, the care pathway worked well in some settings, and poorly in others. Overall though, what strikes me most about the Review Panel’s findings is the lack of patient or family involvement in decision making:

The Liverpool Care Pathway has its own generic document, designed to replace the contemporaneous medical records written by the clinical staff. In some hospitals, training had been supplied for those tasked with filling in the forms. But the Review panel was told that this training can be as little as an hour-long lecture which it was considered acceptable to miss. It was also told that filling this form in could be delegated to the most junior doctor who was sometimes tasked with “completing it at 3 o’clock in the morning”.

Many people recounted that agreement not to attempt cardiopulmonary resuscitation had been taken by the clinical staff as a proxy for agreement to start the LCP, which is clearly unacceptable.

Evidence from relatives and carers strongly suggested that care of the dying elderly is of the greatest concern: the Review panel suspects that age discrimination is occurring, which is unlawful. Nor should old age be taken as a proxy for lack of mental capacity. Each patient lacking capacity, of whatever age, on the LCP or a similar approach, should be represented by an independent advocate.

The Review panel heard many instances of both good and bad decision-making. Repeatedly, they heard stories of relatives or carers visiting a patient, only to discover that without any forewarning there had been a dramatic change in treatment. There now appeared to be no clinical care or palliative care, and the patient appeared to be unnecessarily or excessively sedated. As if caught in the midst of a perfect storm, relatives and carers would discover that a previously sentient person was now semi-comatose. They were told that, following an overnight decision by a relatively junior clinician, this patient had been ‘placed on the pathway.’ One senior consultant who gave evidence to the Review panel related

how a surgical professor was apt to conclude discussions in Multidisciplinary Team meetings about certain patients with ‘this patient is unfit for surgery, so Liverpool Care Pathway.’ This is entirely unacceptable.There were many stories of relatives and carers being handed a leaflet with ‘Liverpool Care Pathway’ on the cover, without any explanation. A common theme among respondents was that they were simply not told that their loved one was dying; this clearly contributed to a failure to understand that the patient was dying, compounded their distress and subsequently their grief, after what they perceived to have been a sudden death.

‘It seemed to us that once he was placed on this plan there was no further review. It seemed that he had simply been written off.’