Coffee is one of the most widely consumed substances in the world. I suppose many drink coffee because they believe it tastes good. But for many, the appeal of coffee is for its medicinal properties-specifically the stimulant effects of caffeine.

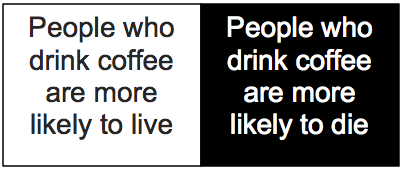

The popularity of coffee and its dual use as a beverage and drug make its health effects an important public health issue. So, it is not surprising that a recent study in the New England Journal of Medicine received a lot of attention. The study had two important findings:

(1) People who drink coffee are more likely to die

(2) People who drink coffee are more likely to live

Huh?

Well, it is actually true. The study really did say both of these things. And in the end, the study does not really answer whether coffee is good or bad for you. But it is worth taking a few moments to try to understand these contradictions. Because if you do understand, you will be a better consumer of the research you read about in the medical literature and the popular press.

The study design is simple enough. The researchers administered a dietary questionaire to nearly 400,000 people between the age of 50 and 71 in 1995. They asked them if they drank coffee, and if so, how much. Then they determined who died by 2008. They compared death rates in those who did not drink coffee, light coffee drinkers, and heavy coffee drinkers.

And after 13 years, coffee drinkers did worse–actually a lot worse. In men, 13.1% of those who did not drink coffee died. 18.8% of those who drank 6 or more cups of coffee per day died. In women, 10.4% of those who did not drink coffee died. 15% of those who drank 6 or more cups of coffee per day died. This sure seems bad. No more Ventis for me. Oh Well. Perhaps I can put that $2.25 to better use.

But wait a second. Have you ever heard of the concept of confounding? In medical research studies, a confounder is something that is strongly associated with the risk factor (coffee drinker), that explains its association with the outcome (death). One way to think about this: Up to now, we were assuming that the higher rate of death in coffee drinkers was due to the coffee. But what if coffee drinkers are very different from non coffee drinkers? And what if those differences, rather than coffee consumption is what really explains the higher death rate in coffee drinkers.

Well, as it turns out, coffee drinkers are MUCH different from non coffee drinkers. They actually are a fairly unhealthy group. Most notably, coffee drinkers are much more likely to smoke. For example, in women, 8% of non coffee drinkers smoke, while 48% of those drinking more than 6 cups a day smoke. Coffee drinkers are also less physically active and have worse dietary habits. Could it be all this bad stuff (confounders), rather than the coffee that is leading to more deaths in coffee drinkers?

It turns out that if one can measure a confounder, it is pretty easy for the researchers to account for it. The researchers are able to use statistical tools to adjust for these confounders. This makes it possible to see what the difference in mortality would be if rates of smoking and other measured health markers were the same in coffee drinkers and nondrinkers. The point of these statistical procedures is to get closer to the truth by making apples to apples comparisons. For example, how would mortality rates compare in nonsmokers who don’t drink coffee and nonsmokers who do drink coffee.

The result of this statistical adjustment is a rather stunning reversal of fortune for coffee drinkers. After accounting for all of the bad health habits of coffee drinkers, those who drink coffee actually have a lower risk of death than those who do not drink coffee. Men who drink 6 or more cups of coffee a day have a 10% lower risk of death than those who do not drink coffee. 6 or more cups in women is associated with a 15% lower risk of death. If you smoke and drink coffee, you live longer than if you smoke and don’t drink coffee. If you don’t smoke and drink coffee, you live longer than if you don’t smoke and don’t drink coffee.

So, coffee is good for you? Well not so fast. While it is true that researchers can statistically correct for confounders like smoking, they can only adjust for confounders that they actually measure. What if there are other unmeasured factors that make the coffee drinkers live longer? For example, what if wealthy people are more likely to drink coffee? What is people who have more medical problems drink less coffee? The study was able to do little to account for either of these highly plausible scenarios. It is quite possible the better outcomes of coffee drinkers have nothing to do with coffee.

So, the study first showed that coffee drinkers are more likely to die. When the researchers accounted for smoking, coffee drinkers were less likely to die. It is possible if they were able to account for additional differences between those who do and do not drink coffee, the results would swing back in the other direction.

So, in the end, we still do not know whether coffee is good or bad for you. (My best guess–it is probably neutral–drink coffee is you like coffee. If you don’t like coffee, drink something else).

In the end, the most important lesson: Have some healthy skepticism when you read the latest news in your medical journals or newspaper about which foods are good or bad for you.

by: Ken Covinsky (@geri_doc)