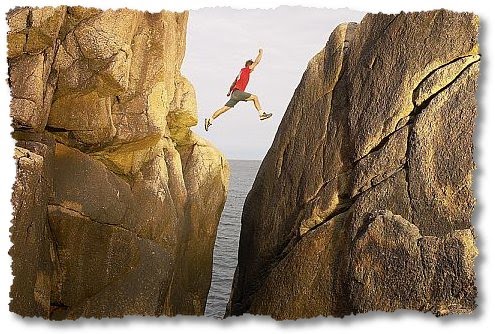

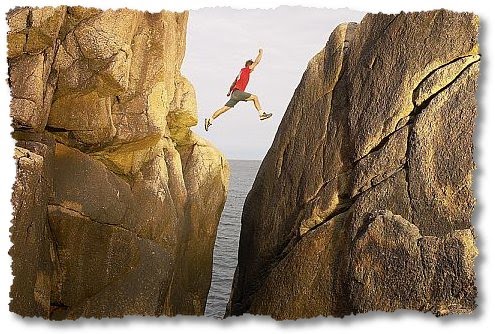

As the health reform debates continue, I am struck by the lack of attention to what seems to be a critical issue in poor health care delivery. With the technologizing of medicine (and more recently the hospitalist “movement”), delivery of health care has come to be centralized around acute care hospitals. Over time, patient care has been divided into acute inpatient care and ‘ambulatory’ outpatient care. While transitions of care, hospital-at-home, and health reform measures such as Accountable Care Organizations attempt to address the divide between inpatient and outpatient care, I keep wondering when providers, change-makers, and policy advocates are going to discuss an inherent problem in the separation of inpatient and outpatient care. The current reimbursement system through Medicare provides a clear example of the problem in defining inpatient care as one thing and outpatient care on the other extreme–when we all know that patients are the same individual regardless of setting. The inpatient-outpatient divide is akin to the systems-based division of care for patients who see cardiologists, pulmonologists, nephrologists without adequate primary care attention to whole-person care. How did we come to define certain types of care as inpatient only and others as outpatient? Barring physiologic instability in a patient, we have the capacity to perform many highly technical procedures on an outpatient basis and to do so safely. Yet we continue to insist that certain types of care require patients to be “admitted” for reimbursement–a sure means to increasing costs, occupying hospital beds which could be better allocated to more ill patients, stressing limited workforces, and, most importantly, forcing patients into hospital environments that they wish not to be in.

As the health reform debates continue, I am struck by the lack of attention to what seems to be a critical issue in poor health care delivery. With the technologizing of medicine (and more recently the hospitalist “movement”), delivery of health care has come to be centralized around acute care hospitals. Over time, patient care has been divided into acute inpatient care and ‘ambulatory’ outpatient care. While transitions of care, hospital-at-home, and health reform measures such as Accountable Care Organizations attempt to address the divide between inpatient and outpatient care, I keep wondering when providers, change-makers, and policy advocates are going to discuss an inherent problem in the separation of inpatient and outpatient care. The current reimbursement system through Medicare provides a clear example of the problem in defining inpatient care as one thing and outpatient care on the other extreme–when we all know that patients are the same individual regardless of setting. The inpatient-outpatient divide is akin to the systems-based division of care for patients who see cardiologists, pulmonologists, nephrologists without adequate primary care attention to whole-person care. How did we come to define certain types of care as inpatient only and others as outpatient? Barring physiologic instability in a patient, we have the capacity to perform many highly technical procedures on an outpatient basis and to do so safely. Yet we continue to insist that certain types of care require patients to be “admitted” for reimbursement–a sure means to increasing costs, occupying hospital beds which could be better allocated to more ill patients, stressing limited workforces, and, most importantly, forcing patients into hospital environments that they wish not to be in.

Recent events with two of my patients illustrate this problem.

A gentleman I see on housecalls with hospice has clearly stated his desire to not be hospitalized. With his level of frailty and the excellent palliation through hospice, this didn’t seem to be an issue until his nephrostomy tube came out. While he has been preparing himself to die within a matter of months, he wasn’t ready to die from urinary obstruction and renal failure in a matter of a few weeks. His first great grandson had just been born. We had a long discussion and he chose to have the nephrostomy tube reinserted. With the hospice medical director’s agreement, I made arrangements for him to be transported to the local hospital for the procedure. Our plan was to transport him in, have the tube replaced, and to bring him right home where he had excellent caregiving. Unfortunately, in order for the hospice to be reimbursed for this intervention, he had to be admitted as an inpatient for an overnight stay. My patient asked me why he had to stay overnight. It reinforced for me how ludicrous some protocols and requirements are under current DRG/inpatient-driven reimbursement processes. As such, what could have been a simple, cheaper, more patient-friendly few-hours event was drawn out into a more costly, more resource-heavy, and assuredly less patient-friendly 24h stay in a hospital.

Similarly, another patient I care for with dementia recently fell and broke her hip. After a series of discussions with the family, orthopedic surgeon, and anesthesiologist, we agreed on non-surgical management to preserve what cognition she has left as she was, remarkably, having minimal pain from her fracture. The care plan for convalescence and subsequent rehabilitation to teach slide board transfers and possible weight-bearing transfers after 6 weeks was discussed with the orthopedist prior to discharge. It took considerable coaxing and authorizations for us to arrange for the SNF as they at first declined since hip fracture rehabilitation is normally only covered post-surgery. And, now safely convalescing at the SNF, the patient is being asked to see the orthopedic surgeon to get an “OK.” The situation leaves me frustrated on multiple levels: a) orthopedic surgeons understandably don’t make housecalls/SNF visits and so this would require gurney transport to clinic, b) we had already made decisions for non-surgical care and the orthopedist had ‘signed off’ in the hospital so an outpatient visit to the orthopedic office was rather useless in this situation, c) that rehabilitation-potential is defined so narrowly for our frail geriatric patients that they must have surgery after a hip fracture rather than considering the potential that non-fixed hip fracture patients may still have to sit up, slide, or transfer into wheelchairs for mobility and to interact with others.

Patient’s experiences with illness are fluid. But care delivery is (literally) broken–and, frankly, often seems haphazard. How would it be if we reformed health care delivery to truly be patient-friendly, to provide care in the settings patients wish to be in (especially when it is feasible and cheaper!) and to reduce the divide we have created over time between inpatient and outpatient care? What if we dispelled regulations that require patients to have “qualifying stays” in the hospital or qualifying procedures in order to access the myriad intermediate and home-based options that exist and could be better integrated to care for our patients?