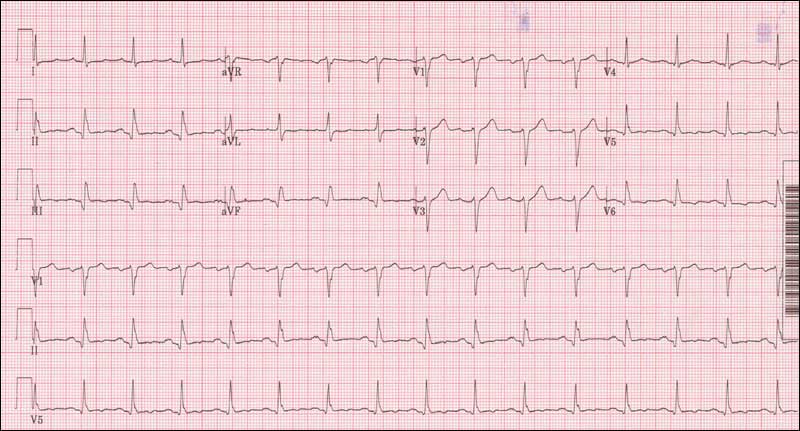

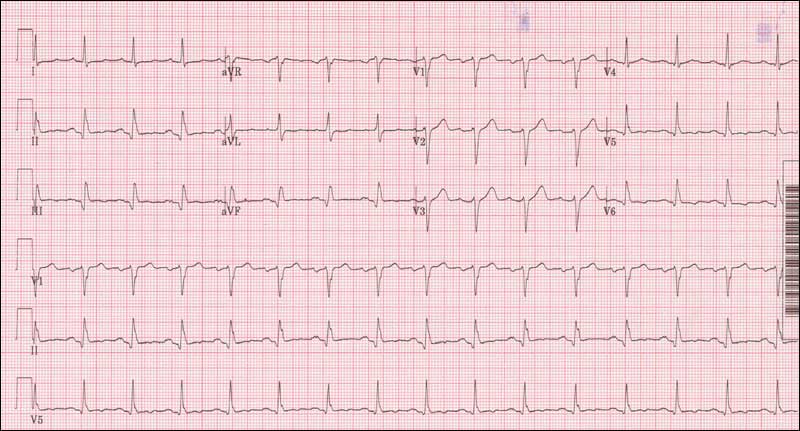

On my last day of ward attending, I handed out an EKG that resembled the Dow Jones industrial average over the last 10 years (not pictured). The normal pattern of an EKG was completely disrupted: ST segments were markedly elevated, P waves were hidden, and beats were grouped in odd patterns. My medical team laughed and shook their heads. I asked why. A brave intern responded that he was completely at a loss. Over the previous two weeks, our teaching rounds began with an EKG every day. We had developed a structured approach to reading EKG’s, albeit with simpler tracings. Someone finally said, “OK, let’s start with the first step – what is the rate: normal, fast, or slow?” Immediately, the focus shifted, from fear and doubt to problem solving. Patterns emerged. Small details contributed to a cohesive understanding. And the students and house officers realized that they could do this. By breaking a seemingly insoluble problem into smaller, more manageable steps, these trainees succeeded in interpreting an EKG that would have challenged a cardiology fellow.

On my last day of ward attending, I handed out an EKG that resembled the Dow Jones industrial average over the last 10 years (not pictured). The normal pattern of an EKG was completely disrupted: ST segments were markedly elevated, P waves were hidden, and beats were grouped in odd patterns. My medical team laughed and shook their heads. I asked why. A brave intern responded that he was completely at a loss. Over the previous two weeks, our teaching rounds began with an EKG every day. We had developed a structured approach to reading EKG’s, albeit with simpler tracings. Someone finally said, “OK, let’s start with the first step – what is the rate: normal, fast, or slow?” Immediately, the focus shifted, from fear and doubt to problem solving. Patterns emerged. Small details contributed to a cohesive understanding. And the students and house officers realized that they could do this. By breaking a seemingly insoluble problem into smaller, more manageable steps, these trainees succeeded in interpreting an EKG that would have challenged a cardiology fellow.

We moved on to discuss a challenging conflict that occurred during a recent family meeting. The patient was in her 80’s, had advanced dementia, and had experienced a precipitous decline in her health status since suffering a compression fracture one month prior to admission. She no longer walked due to back pain. She had developed bedsores. She was admitted to our service with urosepsis, her third admission in the last month. In the family meeting, the patient’s husband agreed to the suggestion that she not be resuscitated in the event of a cardiac arrest. The patient’s son and daughter, however, strongly opposed a “Do-Not-Resuscitate Order,” saying, “We want everything done for our mother.” I asked the intern, who ran the family meeting, how he felt when this conflict came up. He said that while he wanted to support the husband, he didn’t know what to say to the adult children. He felt he had lost control, as family members had begun talking over each other and the medical team, and tensions were rising. I passed out an article published in the Annals of Internal Medicine by Quillet al., “Discussing Treatment Preferences With Patients Who Want ‘Everything.’” This terrific article describes a structured approach to addressing these issues with patients and families, beginning with an examination of the underlying reasons and emotions behind the request, an exploration of the benefits and burdens of treatment options and their alternatives, and culminating with a recommendation for care that encompasses what is known about the patient’s values and preferences. We role-played the family meeting, with the other house officers playing the part of family members. The intern used the suggested structure and his own words. He still struggled, and we had to rewind a few times to play parts over, but ultimately he learned, and felt more prepared to run a “real world” family meeting.

Before rounds were over, we compared the two experiences: the EKG and the family meeting. In each case, my trainees had felt at a loss, inadequate to the task, not knowing where to begin. In each case, a structured approach had helped them work through the problem. In the case of the EKG, however, a structured approach was more familiar to the trainees, whereas a structured approach to communication challenges was novel. The contrast to them was striking. It was the juxtaposition that brought the message home to my trainees: fundamentally, communication is a skill that can be learned, in the same structured way that performing a lumbar puncture, or interpreting an ABG, or reading an EKG can be learned.