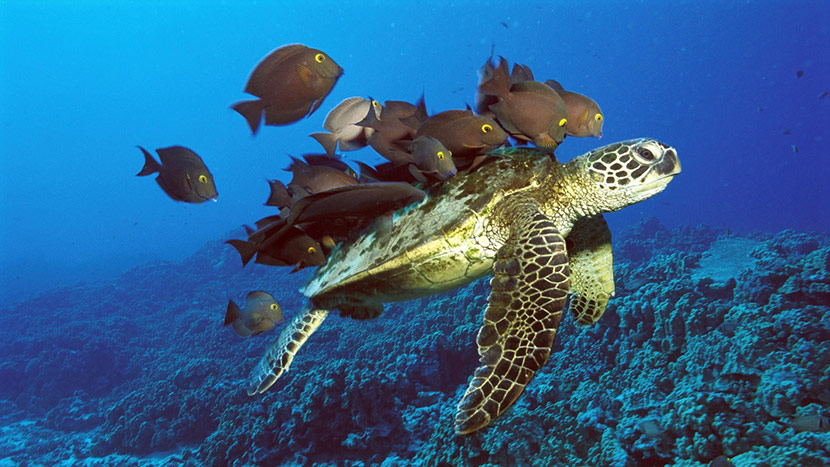

Symbiosis. Remember the idea that the fish and the sea turtles live in symbiosis? The fish eat the algae and parasites off the sea turtles back, and the turtles get a free shell cleaning. Both are rewarded. (You’re wondering why I’m talking about sea turtles and fish. OK, I’m in Hawaii and just heard this example from a naturalist/kayak instructor).

The ideal of co-managment is symbiosis: both clinicians contributing symbiotically to make each other better, resulting in better care for patients.

I can’t think of a higher example of a symbiotic relationship between clinicians than what Vicki Jackson, Chief of Palliative Care at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), and David Ryan, Chief of Oncology at MGH have achieved.

It shines through in this weeks podcast. We challenged them on a few occasions about their terrific new book “Living with Cancer.” Listen to how they tell the story of learning from each other, working with each other, and making each other better clinicians. To the point that they decided to write this book TOGETHER.

For our readers and listeners, who are primarily clinicians, this is a book for any of your friends or relatives who, newly diagnosed with cancer, calls you to ask, “What do I need to know about x cancer?”

This book is a thorough resource, almost a textbook, of a palliative oncology approach to cancer. For example, they reframe the initial clinical encounter with the oncologist, remarkably suggesting that patients first question to the the oncologist should be about goals of care, “What is the goal of treatment?” Toward the end there is a remarkable chapter where they talk plainly about types of deaths that are preferable, and “bad” deaths to be avoided (they had to fight to keep this chapter in the book).

Key quotes:

- David: The hardest thing I think we do in the oncology clinic, and palliative care has been a great help with us, is prognostic awareness. I think that, we decided we thought long and hard about how to frame these first oncology meetings. I always try to meeting with people for the first time, and Vicki can attest to this, I always spend the bulk of the time at the end talking about what is our goal of treatment. Is it to … and there’s really only three things we can do for any patient sitting across from us, right? You can cure them. You can help them live longer or you can help them feel better. So, we talk about that in the book. It’s cure, live longer, feel better. Once you get patients oriented around those three topics, everything else kind of falls into place.

- Vicki: This whole idea of pairing hope and worry became to me from a patient of mine. Who actually, when I was doing fellowship he was in his 20’s and he said to me “Vicki, I want you always to be hopeful and always honest.” And I was like, “Ooooo, how do I do that?” Right? I said to him “What if I had information that is honest but not particularly hopeful?” And he said, “I just want to know that you hope I would beat those odds.”…So, I think if we can continue that human connection, we don’t have to be perfect. We’re just trying to help them, help patients and families, so they can make decisions that feel right given what our best estimate is.

- David: I think we came to the conclusion that there’s not an oncologist or a pilot care clinician who can’t bring up a patient when you ask them “Do you believe in a bad death? Would you want to die that way?” All of us who’ve done this over and over again, know exactly what we mean when we say bad death. Inevitably, a bad death is the opposite of what Monica experienced in the story. There wasn’t acceptance. There wasn’t a family around to help to take care and there were symptoms that Monica had that were easily controllable. If you don’t have acceptance, if you don’t have friends and family around to help you, and if you have terrible symptoms that are out of control, that’s a bad death. While some of it is out of our control, a lot of it is within our control and I think this chapter, the reason why we decided to ultimately go with it, is to make that point. In clinic we are always trying to tell people, in fact we are arguing with patients, I would say more often than not, not to do chemotherapy. Not to keep pursing that clinical trial. Not to go for that phase 1 trial that is available in New York or Boston or Philly.

Enjoy!

By: Alex Smith, @AlexSmithMD

Eric: Welcome to the GeriPal Podcast. This is Eric Widera.

Alex: This

is Alex Smith.

Eric: And Alex, who are our guest today?

Alex: We have

our first repeat guest today. We have Vicki Jackson, who is Chief of Palliative Care at the

Massachusetts General Hospital and she’s joined today by David Ryan who is Chief of

Hematology/Oncology at Massachusetts General Hospital.

Welcome to the GeriPal

Podcast.

David: Thank you.

Vicki: Thanks guys, great to be back.

Eric: We start out with asking our guest for a song for Alex to sing. Do you have one

for Alex?

David: Sure. Springsteen’s “The Promised Land.”

Alex:

Alright.

Alex sings “The Promised Land” by Bruce Springsteen.

Vicki:

Bravo.

Eric: That was awesome.

Alex: So, you wrote a book together:

Living With Cancer: A Step-by-Step Guide for Coping Medically and Emotionally with a Serious

Diagnosis.

Vicki: We did.

Alex: We’re excited to talk to you about

this book. My first question is how did you come to decide to write this book together?

David: So Vicki and I do …Every other week we do rounds up on the in-patient

service and it’s basically tough cases that are on the floor that the residents and the nurse

practitioners are struggling with. As usual, we have to wait for them because it’s 11:00 and

they’ve got a lot of things going on and Vicki and I were sitting there and I said “Hey, Vic,

do you have to call back friends of friends, and friends of family with cancer diagnosis and

explain what’s going on and how to understand the diagnosis, the cancer and the treatment and

the end of life stuff?” She said, “All the time.”

David: And I said “Do you tell

the same stories over and over again?” She said, “All the time.” I said to Vic “Why don’t we

write that down together and talk about all the stories that we tell patients to help them

understand what they’re going through and how bout we have a book that’s like ‘What to Expect

When You’re Expecting?’ Except it’s not for pregnancy.”

Alex: Good analogy. That’s

great. And tell us about the process of writing this book together. How does that work?

Vicki: Wow. I would say Dave and I have learned a lot in this that we didn’t know at

all both being sort of in an academic and medical institution and not having ever written a

book before. We actually had to get an agent to help us sort of figure out how to navigate

this. Then had to get … We have a writer, who is a medical writer, who helped us sort of

take the stories and the information and make sure that it was really accessible.

The thing that we didn’t know is basically before you write a book, you have to write a

book proposal. Which is every single chapter … A portion of every single chapter in entire

chapters and I think ours is 80 pages. Something like that.

David: Right.

Vicki: Then they shop it around to different publishing houses. And the thing that was

really interesting for Dave and I in this, is that there were a bunch of commercial houses

that were like “This is great. You guys are great. It’s a fabulous book. Fabulous idea, but

could you take out that scary last part of the book and then put in something about

nutrition? Something like that?”

Dave and I were pretty clear that that just

wasn’t the book we were gonna write and if we couldn’t have anyone interested in this book,

then we just weren’t gonna do it. Thankfully, John Hopkins University Press was interested in

it. We kinda went from there, but it was three years start to finish?

David: Yup.

Three years.

Vicki: Three years start to finish. A lot of writing on Sunday

mornings.

Eric: Now it also seems like you include language -which is incredibly

important- you include some fairly detailed language using specific diagnoses words that

often that are not discussed in the lay press. I can’t remember

Alex: NK1

inhibitors, 5HT antagonists. Specific types of adjuvant chemotherapy etc.

David:

So we wanted it to be accessible, but not dumbed down. So we wanted this to be something that

patients and families, when they’re taking notes in front of us could go back and say “Okay,

what she’d say? What did he say?” And go to this specific chapter on nausea or diarrhea or

whatever it was and then match up their pill bottles and say “Oh I get it now. I remember

what he said. He said just like it is here.” And we got great feedback on the symptoms

chapters from … Turns out Hopkins sends it out to oncologist and physicians to review. The

symptom chapters came back with great reviews. They almost had nothing to say. They said “Can

I send this out to my patients ’cause it’s a perfect little review for patients.”

Alex: I can imagine that patients hear these words all the time like pneumonitis and

neutropenia, which generally probably makes no sense to the vast majority of patients and

family care givers. But they’re gonna hear it. Did that come into the thinking too? Is that

we have to label these words as they would hear it in the medical system?

Vicki:

Yeah. I think the way Dave and I really thought about this was when we meet patients for the

first time the way I frame it and the outpatient clinic is, “My goal is for you to become a

competent capable cancer patient. I wish you didn’t have to, but you will and we’re gonna

help you do that. Part of the way to do that is to educate you and empower you to ask

questions.” So we felt that, we were going to try and let them in on what we were thinking as

the clinicians and how we frame these issues and the different tools in their tool box that

they could ask their clinical team about.

So we really did try to make sure that

it would be something that would be useful and as Dave said, not dumbed down. This is about

empowering people to understand themselves and understand how they can advocate for

themselves.

Alex: Have you gotten feedback from patients or family members?

David: Yeah. Yeah, I was really scared that the patients, my current patients,

wouldn’t like it. Because, we had done these videos. I’d done a few media things in the past.

My past experience was that the current patients hate it because it’s very truthful and

honest and the patients’ family members or my old patients loved it. So, I was really worried

that the current patients were going to hate it. But, we have had great feedback. In fact,

the patients knew we were writing it, and when it came out, they all bought books and then

they all brought them into be signed. They said different parts of it that they really liked.

Alex: We should mention at this point that we’re gonna have a link to the book,

on the GeriPal post and you can find the book there. I wanted to ask you a question about …

So the first question that you suggest they ask their oncologist. The first question you want

to ask after staging is, “What the oncologist hope the treatment will do for you?” What is the goal of

treatment. By knowing the goal of treatment you can choose the options that are right for

you. It strikes me that … I don’t know that I ever have or heard of a patient ask their

oncologist, that boldly, about the goal of treatment up front. Is this something that’s

starting to happen in clinical encounters with new diagnosed patients?

David: So

that’s a great question. We just … the thing we wanted to impart about that was the

beginning of understanding prognosis. The hardest thing I think we do in the oncology clinic,

and palliative care has been a great help with us, is prognostic awareness. I think that, we

decided we thought long and hard about how to frame these first oncology meetings. I always

try to meeting with people for the first time, and Vicki can attest to this, I always spend

the bulk of the time at the end talking about what is our goal of treatment. Is it to … and

there’s really only three things we can do for any patient sitting across from us, right? You

can cure them. You can help them live longer or you can help them feel better. So, we talk

about that in the book. It’s cure, live longer, feel better. Once you get patients oriented

around those three topics, everything else kind of falls into place.

If you

decide to take shortcuts, or ignore that I’ve always found in my own practice I’m backing up.

So every time I’m sitting and talking to an initial patient, I’m saying “Are we trying to

cure you? We trying to help you live longer/ We trying to help you feel better?”

Eric: So that seems like much more accessible language than remission, response,

progression

David: Yeah. Yeah. And I don’t think we do good job of teaching the

fellows, particularly the oncology fellows on how to communicate that in a good way.

Alex: This is terrific. It makes my pilot of care heart sing. Starting the

conversation with the oncologist from the get-go by orienting around goals of care. This is

amazing! This will be a sea of change, right? If we can activate patients to get their

oncologist to refocus from the get-go from on goals of care. That would be amazing actually.

Vicki: Well you see why I love working here. But I think the other thing, to be

straight up about though guys, I, for the last fifteen years been hanging out with a lot of

oncologist, right? And I see them do this, and I see Dave do this and patients variably

uptake that information. Even though the oncologist’s been really straight about it and in

very plain language. Part of that piece that we also had to do over the years with talking

with the oncologists is saying “Okay, just so you know, you’ve done a beautiful job there.

The patient didn’t integrate that. They’re going to come back again in a month and ask you

‘What do I have to do to be cured?’ And Dave I don’t want you to think you did a crappy job

there, because you didn’t. This is just how … Right now, they’re not able to integrate that

information.” I think that sort of triadic relationship really helped, because I get it. If a

patient of Dave’s doesn’t understand, I don’t think it’s because Dave didn’t say it, and Dave

doesn’t think I think he’s a bad guy that he didn’t do it, we just know that this is how it

goes.

David: I would say 15 years ago when we started this project that seen

patients together in the cancer clinic, it wasn’t that way. I know that I always the

palliative care doctor thought I was a jerk. I didn’t talk to my patients and didn’t really

communicate. I always thought that I did a really good job of taking care of patients

symptoms. I’d say the two biggest lessons, I mean there’s a bunch of lessons that we’ve

learned from working with one another … I’d say the two biggest lessons that we’ve learned

are: A) I wasn’t doing a good job taking care of my patients symptoms. In part, because

you’re so rushed in clinic that you’re thinking about the chemo and the dose and getting them

upstairs to infusion. Is that port working? The nurse is yelling at you about not flushing

properly and yadeyadayada and then you never get to their diarrhea.

On the flip

side, what the pilot of care doctors learned was that it wasn’t that the oncologist … now

maybe 15 years ago some oncologist weren’t talking this way… Bbt it wasn’t so much the

oncologist weren’t communicating, it was that the patient weren’t hearing and maybe the

oncologist thought the patient heard and just never kinda went back to it.

Alex:

I want to continue on this vein about prognosis and introducing the idea prognostic

awareness. You have a section in one of the next chapters on survival rates and how

statistics themselves can be misleading. I’m looking at page 37 here. I thought it might be

interesting if we can ask one of you to read this section. My guess is Dave, you wrote this

section here when you say, “I work with two patients whose experiences with cancer were the

opposite of what the statistics indicated.”

David: Oh yeah. So, Melissa had stage

one colon cancer and a 90% chance of being alive in 5 years. And I told her so. Joanne had

stage 4 colon cancer and the survival statistics indicated that she had 10% chance of being

alive in 5 years. That was a difficult discussion. But I believe that doctors should talk

about what might happen if the treatments don’t work as well as we hoped. I was thrilled when

Joanne’s cancer responded wonderfully to therapy and even happier when she underwent surgery

and had the tumor removed.

Five years later, Joanne scolded me, saying I should

never tell anyone their survival statistics. She said she had lived in terror during that

first year thinking each holiday and family birthday would be her last.

Melissa

wasn’t so fortunate. Despite having very hopeful survival statistic, her cancer returned in

the fourth year after treatment. It became clear that the cancer had spread. She told me that

I should have warned her more strongly that this was a possibility. She said that she would

have lived differently if she had realized that time was so short.

Alex: Hmmm. One

of the things that strikes me about this book is how the stories illustrate the point. But

also sometimes the stories are surprising and they don’t go the way that you think they’re

going to go, like these two stories here. I wanted to ask you a little bit more how

palliative docs and oncologist should talk about prognosis with patients who are newly

diagnosed with cancer, given that statistics can be wrong. People are individuals, they’re

not averages and yet there is some valuable information there that what happens to groups of

patients like the patient in front of you.

Vicki: Yeah, it’s a great question. I

think the way we talk with patients and teach other to talk with patients, is we really love

pairing hope and worry. So it’s a way to get some broad scope of we’re hoping that you can do

well for a couple of years. We also worry that because we see these other things that time

could be shorter. And often just people are not … What I think clinicians and hopefully

pilot of care clinicians don’t worry about this, but I think what many clinicians were not

trained and us worry about is that we’re going to be wrong and then the patient is going to

hold us to that and we’ve either over or underestimated and we lose all credibility.

And I think this … I don’t know if I’ve said this to either of you before, but this

whole idea of pairing hope and worry became to me from a patient of mine. Who actually, when

I was doing fellowship he was in his 20’s and he said to me “Vicki, I want you always to be

hopeful and always honest.” And I was like, “Ooooo, how do I do that?” Right? I said to him

“What if I had information that is honest but not particularly hopeful?” And he said, “I just

want to know that you hope I would beat those odds.”

And I think that is a way

to be very genuinely connected and I think I would have to say in my clinical experience,

when I’ve been wrong and people have lived much longer … Like I remember a patient of mine

who was actually a hospice medical director who asked me for a time based prognostic

disclosure, and he said “How long do you think I have?” I said ” You know, I hope I’m wrong,

I worry it could be as short as a few weeks.” And he was going home with hospice and he had a

delayed response to chemotherapy and lived another nine months. He came back to see me in

clinic he’s said to me. ” You know, I’m doing great.” I said “How do you feel about the fact

that I was wrong?” And he said “Well you said you’d hope I’d be right, so I just thought

you’d be happy.” I thought you’re absolutely right, I’m thrilled that I was wrong.

So, I think if we can continue that human connection, we don’t have to be perfect. We’re

just trying to help them, help patients and families, so they can make decisions that feel

right given what our best estimate is.

Eric: I think that’s a great analogy. I

always think about it like, don’t tell our listener audience, but I play the lottery

occasionally. I know I’m not gonna win the lottery. Like what are the statistics? One in 500

million? But I hope I will.

Vicki: That’s right.

Eric: And yo can

tell me “No, Eric, you’re not going to win the lottery” I’ll think that’s kind of rude, I’m

still hoping. You can’t take away my hope. But like, I know I worry I may not win it. I worry

that I should not put my retirement ideas solely based on my hope for winning the lottery.

David: Yeah you know, it was purposeful that we use that story. That story actually

happened to me and I’ve actually since that story happened often in the first visit

particularly around adjuvant chemotherapy, it doesn’t work so well in the metastatic setting.

But around adjuvant setting, it works really well. I think the reason it works well, is that

the person who wasn’t suppose to do well, did really well and the person who was suppose to

do great did really poorly. And so, it switches it and makes people think for a second. In

that process of thinking all of a sudden the emotion gets crowded out by the thinking. It

allows people to focus. I’ve found that’s story is a great tool to help people understand

that issues that we have with statistics. It frames it in terms of best case, worst case

scenario.

Alex: Right.

Alex: So what is this section that struck me is

maybe because this comes up so often in clinical work with patients with serious illness and

you see this so often in TV – John McCain just diagnosed with cancer, right? And all of the

messages are about positive thinking and he’s a fighter.

Eric: He’s gonna fight

this cancer.

Alex: He’s gonna fight this. Right? So, you have a section in your

book. I’m looking on page 242, 243 on the negative power of positive thinking. And I wonder

if there’s a section of this you might read for example the story about Julie. I think, Vicki

perhaps you write this? I’m not sure.

Vicki: Well, you know just to be clear, we

would alternate back and forth writing chapters, but then we would edit each other’s

chapters. So I think, we can’t even remember who wrote what anymore. Because if it became

between us and Michelle, it’s all blur. So we just we kind of run with it.

So

this is really thinking about the unfortunate negative power of positive thinking.

I had a patient recently, Julie, who was having a lot of trouble sleeping. She had trouble

falling asleep at night and would wake up at 2 or 3 in the morning with her mind racing. I

asked her what she was thinking about when she couldn’t sleep, but she didn’t want to tell me

at first. Finally, she admitted she was worrying about what would happen if her cancer got

worse. She worried about her husband and how he would care for her if she were really sick

and how she would be letting him down if she didn’t get better. Then she sat up straighter

and said, “But I can’t think like that. I have to stay positive.” She wasn’t really talking

to me at that point she was lecturing herself. She also said that if she didn’t stay

optimistic, she was inviting her cancer to grow.

Alex: So why do you say to

patients, when their family members, when they say “We have to stay positive. We can’t talk

about this.”

Vicki: Yeah. I would say in palliative care, I ask patients how

they’re sleeping because it’s actually a really important key question. Really, I think with

understanding how much anxiety their having even when they don’t endorse anxiety when I ask

them about it. Also with how comfortable they are with what their illness understand is and

how much they can tolerate emotionally, being able to think about a likely illness

trajectory.

So what I say to patients, is – and we try to teach them strategies

about how to deal with that intense emotion- I say to them, “you know the reality is the fact

anybody who has cancer, curable or not. If they don’t have times that they were worrying

about what the future holds, that would be crazy. Cause that’s just not normal. Everybody

should be worried about it.”

And what I say to them and what I notice in my

patients is that, sometimes there worry if they give voice to that, then that means that

they’re not going to do well, that they’re going to give up, that they’re going to become

depressed. Sometimes if people want to know data about it, I say our early intervention

studies show the exact opposite. Like being able to have a safe space to have these

conversations. Actually is associated with people having a better quality of life, less

depression. I typically say to them, I think it impossible, no matter how strong you are, to

block all those thoughts out. Typically what happens, is they come up at 3 in the morning and

bite you in the backside.

So we have two choices to either completely try to

block it out, which unfortunately I think is just not successful, or find a way that doesn’t

feel overwhelming to begin a dialog about these things. For people who are super resistant,

we do what I call “talking about talking about it.” I’ll say “What would that look like to

start talking about these topics. Who would be there? Would you want to make a list? Should

it be on a week that you’re getting chemo or not?” It’s a really kind of motivational

interviewing sort of approach.

Then folks who are really more open to it, we

sometimes use this, and a patient taught me this idea of using the box metaphor, which we

write in the book too. Is to say “You know what? All these things that you’re worried about,

let’s sort of put them in this box and use that to, sort of, contain it and compartmentalize

it. And that we can decide together when we are gonna open the box and how long the box stays

open and when you’re gonna close the box.” Because patients will often say to me they worry

if they start talking about these hard things, that they’re never gonna stop and then it just

feels so overwhelming and flooding.

So it’s some conversation like that. I try

it for a little bit. What if we open the box and talk about one thing that feels tough when

you’re thinking about what keeps you up at night. Let’s do that for a bit and see how that

goes. Then you can close the box.

So to typically my goal is to have them feel

safe and connected, but build the emotional and intellectual muscles to look at these hard

topics.

Eric: Those are two great keys right there. Especially the sleep question.

I never thought about that. I just think about myself. I do all my worrying right before I go

to sleep lying in bed and then I can’t go to sleep cause I’m worrying so much.

Vicki: Yeah… Yeah exactly.

Alex: I wanted to ask you about a section that

comes toward the end of the book, where you talk about the good death in Chapter 24 here. And

also what a bad death is and I think there’s some controversy about using these terms like is

there such a thing as a good death? Is there such a thing as a bad death? This ties in with a

little but about the way the bat of ethics is swung and the norms of what’s acceptable for

doctors in society. And it’s swung from “doctors know best” the other way towards “we should

respect patients what their preferences, their goals and values, even if that means dying in

the ICU.” I think it maybe swing back the other way because as you write about here, you do

have a conception what a bad death is. And you even label dying in the ICU as a bad death. I

wonder if you could say little bit more about that balance between respecting patients’

preferences, their wishes and coming to it with your own sense of what a good death and a bad

death is.

David: I say we argued and argued about this chapter “What is a good

death?”, more than any other chapter. In fact, Michelle who’s not here felt it was too

negative. She was really upset and then Vicki and I argued about the three lessons and how to

frame the three lessons the story that Monica showed about a good death.

I think

we came to the conclusion that there’s not an oncologist or a pilot care clinician who can’t

bring up a patient when you ask them “Do you believe in a bad death? Would you want to die

that way?” All of us who’ve done this over and over again, know exactly what we mean when we

say bad death. Inevitably, a bad death is the opposite of what Monica experienced in the

story. There wasn’t acceptance. There wasn’t a family around to help to take care and there

were symptoms that Monica had that were easily controllable. If you don’t have acceptance, if

you don’t have friends and family around to help you, and if you have terrible symptoms that

are out of control, that’s a bad death.

While some of it is out of our control,

a lot of it is within our control and I think this chapter, the reason why we decided to

ultimately go with it, is to make that point. In clinic we are always trying to tell people,

in fact we are arguing with patients, I would say more often than not, not to do

chemotherapy. Not to keep pursing that clinical trial. Not to go for that phase 1 trial that

is available in New York or Boston or Philly, which is our access. The perception in the

public and the media is different. They think that we’re … The public is constantly saying

“Don’t. I don’t want to do it. The doctor’s making me do it.” I would say if anybody who’s

done this job, 9 times out of 10, it’s the patients arguing for more and you’re trying to

convince a patient not to. So that’s why… it’s a long winded explanation, but it’s we why we

ultimately said that chapter needs to be there.

Eric: Yeah I think that

interesting thing though, is that there’s probably a lot more influences cause you can open

up magazines and see ads for cancer centers that say, “We won’t give up on you.” You can see

commercials. We had a past Geripals post that included a bunch of commercials of cancer

centers saying “we will never give up on you ” or “Do you want to fight? Come to us.” And

even with messages like John McCain it’s … There is this battle analogy where it’s like a

good vs. bad, kinda like, good death vs. bad death. I think that influences that patients may

not even realize that maybe changing how they’re thinking.

Vicki: Right, and I do

think the problem …another really problematic message is the “battle” metaphor. What Dave

and I are continually saying to people is unfortunately, it’s the biology. Right? You haven’t

lost if this cancer progresses. It’s the biology.

I would say for this chapter, I

think one piece that, I think where we settled, was that we wanted to say from our own

experience what we, as what Dave was saying, what we felt like were deaths that could be

different. I think acceptance doesn’t mean like this kumbaya moment, where everybody is great

about it and everybody is all around them like with Monica. That doesn’t happen with

everybody. There are patients who we care for who we try to help them along the way. We have

difficult ones we share sometimes. Those folks may end up that may be necessary that they die

in the intensive care unit.

What I always say when I’m teaching this stuff – you

know we teach a bunch of this stuff in our courses at HMS Center for Palliative care- is, “we

have failed, not if the patient dies in the ICU, we failed if we haven’t tried to talk with

them, about what that role really looked like, what our worries are, and that there are

alternatives. And that we are going to stay partnered with them no matter what happens.

That’s when we fail.”

So, I think the other piece we tried to do with the book

was to have it be honest and open about how we feel and how we’re emotionally connected to

our patients and we feel badly when patients are suffering at the very end of life. It’s

hard. It’s hard for us too.

Eric: So if readers or listeners to this podcast are

interested in learning more about the book, is there a website they can go to?

Vicki: Yeah there is. It’s called livingwithcancerbook.com.

Alex: Great.

Terrific.

Eric: Well, we’d like to thank you both for joining us today. Maybe

Alex can take us out with a little verse at the end?

Alex: Welcome to join in

over there on the East Coast!

Alex sings “The Promised Land” by Bruce

Springsteen.

produced by: Sean Lang-Brown

by: Alexander Smith