“Tell me about the problems you have with your medications.” A simple open-ended question that is probably rarely asked, but goes beyond the traditional problems that clinicians worry about, like non-adherence, inappropriate prescribing, and adverse reactions.

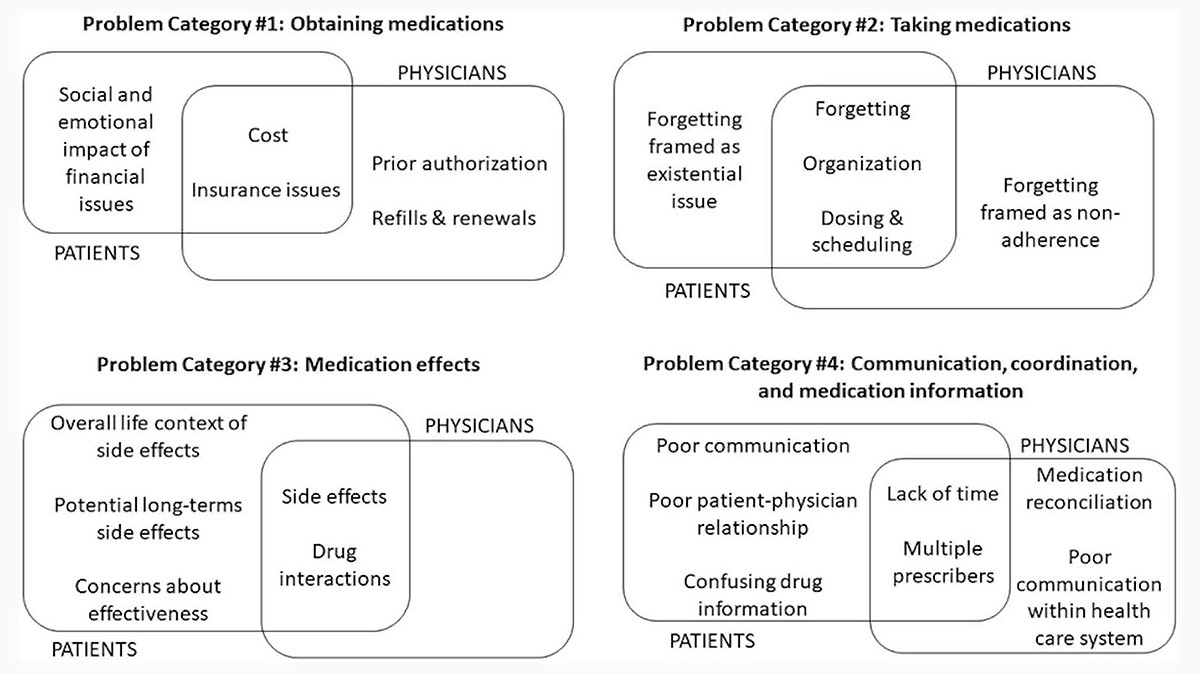

What do you find when you go deeper? Well we talk with Francesca Nicosia and Mike Steinman about the work they have done around deprescribing and medication related problems, including a recent JGIM study that attempts to better understand patient perspectives on medication-related problems. This study also gives a pretty fascinating picture of where the overlap and divergence is between what patients and physician see as medication related problems as shown in this figure from the article:

In addition to medication related problems, we talk about some other important updates in deprescribing, including their work in the newly formed US Deprescribing Research Networkand new pilot awards of up to $60,000 in funds to catalyze investigator initiated research projects around deprescribing.

by: Eric Widera (@ewidera)

Eric: Welcome to the GeriPal Podcast. This is Eric Widera.

Alex: This is Alex Smith.

Eric: And Alex, we have two people in our studio audience.

Alex: We have two people in our studio audience. We have Francesca Nicosia, who is a ethnographer, researcher… I’ve already forgotten everything, but she is associated with both the UCSF Division of Geriatrics and the Institute for Health and Aging. How close was I?

Francesca: Pretty good.

Alex: Pretty good?

Francesca: Yeah.

Alex: Ethnographer, researcher…

Francesca: Medical anthropology.

Alex: Medical anthropologist. Okay.

Francesca: Exactly.

Alex: Great. And we have Mike Steinman. Is this your first podcast, Mike?

Mike: It is.

Alex: Oh, we have been remiss. You’re a treasure right under us. Literally his office is downstairs.

Eric: Right under us.

Alex: Mike Steiman who’s a professor of medicine in USCF Division of Geriatrics and is the co-PI of the US Deprescribing Research Network. Welcome to the GeriPal Podcast, Mike.

Mike: Thank you Alex and Eric.

Eric: All right, so we start off every podcast with a song. So just to give people a preview of what we’re going to be talking about, we’re going to be talking about medication related problems including a JGIM paper that you guys just published titled, What Is a Medication Related Problem: A Qualitative Study of Older Adults. But before we do, song request for Alex.

Francesca: A Spoonful of Sugar.

Alex: Yes. Helps the medicine go down.

Alex: (singing)

Francesca: (singing)

Eric: We’ve got Julie Andrews on too!

Alex: Thank you for your company Julie Francesca Nicosia Andrews.

Eric: You can reach some highs. I want to really hear that. We’re going to do that again at the end…

Alex: Everybody’s going to join at the end.

Eric: You’re ready, Mike?

Mike: You might want to end the podcast a little earlier for listening, but go right ahead. [Laughter]

Eric: All right. So medications, medication adverse events-

Alex: Older adults…

Eric: How did you guys get interested in this? I’m going to turn to you first, Francesca.

Francesca: I got interested specifically in what are medication related problems because Mike had a study that he needed some help with. I mean, aside from just general concerns, being interested in older adults’ health and healthcare, I don’t know. Mike, do you want to talk a little bit about how this project came to be?

Mike: Sure. So I had one of my earliest mentors say that medications are the internist scalpel. It’s what we as many clinicians who aren’t surgical specialists actually do to help patients and it is one of the primary roles that we have. And so it really struck me as both just a clinician in general, but also as a geriatrician that medications are where it’s at in terms of how we can really in many ways help people. And as a geriatrician, I had exposure to seeing the many ways we harm patients with medication. So that got me interested in thinking about ways how we can reduce medication burden as one strategy for actually improving the drugs that people take so that it helps them live better and more consistent with the things that they want and care about.

Alex: Too much scalpel.

Eric: Wait, wait, wait, wait. When I think of medications and the physician scalpel, I think about debreeding medications. Is that what we’re really good at, just making sure that we’re taking off all necessary medications?

Alex: It’s got to be an analogy here for the geriatricians.

Mike: Yeah, I know. Well, it used to be that our prescription pad was our scalpel, but now we don’t really have prescription pads anymore. So the analogy cuts a little less. But if only we did have the scalpel to debreed medications because it’s a whole heck of a lot easier to add something than to take it away. And it’s easy to talk about this, it’s much harder to do it. And I recognize as a man of clinical practice, even as a purported expert in this area, I just find that deprescribing in some ways is much harder than prescribing and therefore it requires more attention to actually do it well.

Alex: So unlike others like Eric or Mike or Ken, I don’t have many tweets that go viral, but one of my tweets was actually a quote from Mike Steinman from, I think one of your grand rounds talks where you said… it was just so tweetable. “Any new symptom in older adult is a medication side effect until proven otherwise.” It’s just a great pearl that is easy to remember and yet is so true. I see that again and again and again. In fact, I’m caring for a patient right now who’s admitted to the hospital and he has pain and cancer, but it’s not cancer pain. It’s pain as a side effect of the medication he’s been taking.

Mike: Really interesting. I mean, these things happen all of the time. As you mentioned, I try to keep that parallel. I certainly can’t claim credit as the inventor of that. I just passed it on. I think if we actually think about it, we can often recognize these potential side effects. Just the challenge is thinking about it because as a clinician, my go-to reflex when I see a new symptom or a complaint is, “Oh, what disease is causing that?” And so unless I take a step back and think, oh, could this be a medication side effect, it’s easy to miss.

Eric: Just a couple ideas of why you think medication deprescribing is so hard to do?

Mike: Well, part of it is the technical aspect. There’s a lot more guidance about how to start medications and how to stop them. How to do a taper effectively, for example. But a big part of it is the psychology. So when we add a medication, there’s a perception that we’re doing something positive to help the patient. But we stop a medication, there are many more barriers. So for example, the condition you might feel like they’re giving up on the patient. If you stop, for example, a medication used to treat a chronic condition or prevent a chronic condition, for example, statin or bisphosphonate for high cholesterol or bone health. And then on the patient’s side, there’s a concern that they might feel like the doctor is giving up on them.

Mike: And then of course there’s the fear of the unknown. Maybe this drug is helping them and will I harm the patient if I stop it, and patients might have similar fears. And then finally there’s all the issue, a lot of times as a clinician I’m dealing with a patient whose medication were prescribed by another clinician. And I don’t know exactly why they were prescribed or exactly the reason for it. But maybe I’m hesitant to stop because maybe the other clinician knows something I don’t know about the patient. So it just creates all these challenges.

Eric: It’s like everybody being on a PPI or gabapentin, no idea why somebody is on it yet they still are on like 300 QHS of gabapentin which probably isn’t doing anything.

Alex: Right. And so many of these issues arise as you’ve shown recently when patients are hospitalized and they get started on new medications or their blood pressure medications get intensified to outpatient guidelines and then they get discharged and sometimes bad things happen.

Mike: Exactly. So you start these medications in the hospital is one of many examples where this can happen and then the medication is on their medication list since once it’s on your med list, then it just has a high chance of being perpetuated. And the issue is not only that patients are paying for something and having to put another pill in their mouth that they probably don’t need in many cases, but actually you can experience the harms.

Alex: So in the setup for this article, you talk about how prior approaches to deprescribing have focused largely on physician centric views around things like adherence. I wonder if you could set up for our readers why it was important here in this paper to go to older adults themselves for the first time and ask them about what a medication related problem is for them.

Mike: I think a big part of it is because we fail a lot. A lot of trials of deprescribing or other interventions to improve medication use are either not effective at all or they’ve been only minimally effective. So clearly we’ve been missing something in how we can actually tackle this problem effectively. So one of the things that got me interested is what if we take a really patient centric view and really try to understand what’s going on from the patient perspective? It doesn’t mean that the clinician perspective isn’t important or should be ignored, but if we don’t really understand what’s going on with patients, we’re not going to be able to meet them where they are.

Mike: And so we’re going to fail in doing the things that we feel are important, but we also might fail the patients because we might be doing things against their will or in ways that make them feel uncomfortable or feel like we’re not taking good care of them.

Alex: And Francesca, you’re a medical anthropologist. Tell us why you chose to approach this issue from a anthropological… if I’m using that word correctly – perspective.

Francesca: Like Mike was saying, I think the importance of including patients and patient understanding of a phenomenon or what’s going on with their experience of their medications is really important. And so from an anthropological perspective, starting in the mid ’70s and into the ’80s, anthropologists were really concerned with looking at the illness experience and illness narratives and understanding how patients understood their lived experience or whatever illness or chronic disease that they had, the treatments that they were going through, and their relationship with their healthcare providers.

Francesca: And so in the early or the mid ’80s, around then, social scientists started to problematize their question, this idea of adherence and compliance as it’s often talked about. And so of course, from a medical perspective, not adhering to medications can cause many problems from a patient centered perspective, just thinking more broadly like why would somebody not be adherent or not compliant to their medications? And so that was the perspective that I brought into this and just really wanting to turn to patients and understand broadly in comparison to these taxonomies of what are medication problems, how do patients think about them?

Eric: Right. Go ahead Mike.

Mike: No, it has been a real pleasure to work with Francesca. As a physician, we’re trained to think that we know everything about everything.

Eric: We don’t?

Mike: Rarely we don’t. But this was one of those rare situations where it was just great to step outside of my usual comfort zone in that clinician perspective and really have a chance to work with Francesca as an anthropologist and think about these things in a different way. Taking advantage of the tools of anthropology and using those to really explore patients’ perspectives in a way that I as a clinician having seen patients for decades, I learned a lot of new stuff just reading the transcripts and thinking about this problem that in retrospect I should have completely identified when I was taking care of patients in the office or in the hospital and I often completely missed.

Eric: So let’s go to the paper. So this article was published in JGIM. And again, it’s focused on medication related problems. Now I think probably for a lot of people, maybe even me like medication related problems, not adherence to medications side effects, okay, I got my list. Is there more? Is that what we’re looking at, not adherence and is that a leading question?

Francesca: Definitely it’s part of it. Those two things are talked about and mentioned in our paper and in our model that we came up with from patient interviews. But I can run down the four main categories of patient identified medication related problems.

Alex: Great. That’d be terrific.

Francesca: Okay. So the first one broadly is obtaining medications. So anything having to do with actually getting the medications. Then the second category is taking medications. So that would include remembering to take medications, how they’re organized, things of that nature. The third category is medication effects. And so that’s where side effects would come in. But we actually found… patients talked about the effects of their medications much more broadly than just side effects. They talked about future side effects. That fear of, well, what might happen down the road. Where we found that physicians actually didn’t really talk about that at all.

Francesca: Another surprising thing regarding effects was that patients actually questioned the effectiveness of their medication sometimes, whereas it’s not something that we heard from physicians, most physicians assumed that the medication would do the thing that it was intended to do. And then the fourth category was just communication and care coordination between healthcare providers, between patients, within the healthcare systems. So anything else to add, Mike?

Mike: No, just to expand on what you were saying, I mean, some of these things, as a clinician you say, “Oh yeah, I knew that.” Sometimes patients forget to take their medicines or sometimes they have a problem with pending them from the pharmacy. But there was this extra layer that we uncovered and you were just talking about this, Francesca, for example, the issue of side effects. As a clinician, I’m thinking all about the side effects patients are experiencing. And people did note that clearly, but a lot of people brought up concern about future side effects. I’m taking this medicine, I’m supposed to take it for a long time, is it going to damage my liver 10, 20 years from now?

Mike: And that really gives me a lot of anxiety today and decreases my quality of life because I’m really worried this medicine’s going to eventually kill me. Or for example, we might think about the patient is not adherent to their medications because they’re forgetting. And as a clinician, we might stop there. But some of the patients said that not only is the issue forgetting, forgetting the medications triggers in them this whole idea of maybe I’m losing my memory and what does that mean for my health and my wellbeing and my future life? So it’s all wrapped in with these other things.

Mike: And then finally it’s the issue of communication with doctors. We as clinicians might think, oh, if I just tell the patient about what the medicine is for and what side effects to look for, I’ve done my job. But for patients, a lot of their perceptions of problems with medications were tied together with their trust in the physician and the nature of the relationship. So it wasn’t just the informational component, it was about establishing trust, feeling like their doctor was listening to them and taking care of them. And that was deeply embedded in the perception of problems.

Mike: And some people who had things that we might classify as side effects or adverse events, the patients weren’t really bothered by them. They just said, “I trust my doctor, I trust it’s the right medicine. I can live with it. That’s okay.” And other patients who had things that we really as a clinician might not think are important or really bothersome or meritorious of attention, patients were really bothered by the actual symptom but also were bothered by the fact of does this mean that my doctor isn’t taking good care of me, should I trust my doctor about future medicines. So there’s this whole extra layer that we uncovered. This goes beyond what I as a clinician typically think about when I see patients.

Alex: You use some big researchy you words in this article like, the older adults in these studies embed the medication related problems in their personal lives and their social, emotional aspects of their lives. And there’re some really nice quotes in your article that illustrate that. I wonder if you would like to read any, for example, taking the first one about financial barriers in this 73 year old woman who was talking about how her medications just got too expensive. I’m going to actually hand it to you so you can read it.

Francesca: So before I read this too, I think you bring up a really good point. And Mike was touching on it regarding this idea of the broader context of people’s medication problems. So this has to do with the social and emotional impact of financial barriers to obtaining medications. So there was a 73 year old woman and she explained how her medications, quote, “Got too expensive, but I got to buy them. That’s why I started going to the food pantry. Eventually I’ll probably have to sell my house and I don’t want to move, start with new friends and new ways to live. I’m too old for that.”

Alex: So this really illustrates… We just did a podcast about food insecurity and this is almost like medication insecurity. Because my medications cost so much, I have to skimp on other things in order to purchase the medications. In that other podcast about food insecurity, we talked about how they might skip their medications so they can buy their food. But the issues seem very analogous to some extent here. And Mike talked earlier just a moment ago about how these issues are relational and incur a medication side effect that might engender distrust in one’s physician for example, or it might build trust conversely if the medication is working effectively for that person.

Alex: In another quote, you talk about this woman or this 82 year old woman who’s talking about the impact of the medications on their daily lives. Because I think as you note here… when we think of side effects, we see this dry list of symptoms or signs that somebody might be having as side effect. But for them it’s really about the impact on their daily lives and being able to participate in activities that are meaningful to them. So you have one nice quote there and another quote about somebody who likes to bicycle or sail. I wonder if you could read some of those or one of those.

Francesca: Sure. So the first one I’ll read… and I really remember doing the interview with this woman. She had multiple chronic health conditions and multiple different medications and the interactions between them, it just caused a lot of problems in her life. And so she was on diuretics. And so she said, “If I’m going to drive an hour away, I have to stop on the way to get off the road and to go to the toilet somewhere. So I either try to hold it or I have to not take the water pill. My granddaughter lives an hour away and I need to see her much this year.”

Alex: So it’s really important to her to go see her granddaughter. And yet if she takes this pill, it means she can’t go see her loved family member. Huge impact on their daily lives.

Francesca: And can I read the second one?

Alex: Yeah. That will be great.

Francesca: And so this person… it actually gets to the issue around… and I think Mike mentioned this – identity. It’s like, well, gosh, if I’m forgetting to take my meds, what does that say about my memory? Am I getting older? In this person it had more to do with how he felt about himself and who he was in the world. And so he said he used to be an avid sailor and a bicyclist and would ride his bike all over the hills of San Francisco. But in recent years he wasn’t able to do that because medical conditions and side effects prevented him from riding his bike. And so he said his doctor would prefer… “My doctor would prefer I didn’t ride a bicycle because of the medications, but if I don’t ride a bicycle, I just feel useless.”

Alex: So here we have medications impacting somebody’s identity. Who are they? How do they see themselves and what is their place in the world? Okay, so the doctors in this study didn’t get these underlying issues, right?

Francesca: I know.

Alex: They complained about the healthcare system. Well, what did the doctors do? Well, what were the problems for the doctors?

Mike: So this was really interesting and I just framed who these doctors were. So we interviewed patients individually in individual interviews, but we interviewed doctors in the context of focus groups. And we had three focus groups with general internists all affiliated with an academic medical center in different practices or some of their practices. And then a group of family physicians and in another community-based but academically affiliated practice. And so these are kinds of people who… they are local institutions, so I know some of them and these are good people. So it’s not like we’re interviewing clinicians who are just not caring or not skilled or not competent in social medicine as well as in more clinical medicine.

Mike: But still the clinicians were first of all focused much more on the concrete problems that we think about, oh, the person’s having side effects or the person can’t afford medications. And often didn’t really get into these deeper layers. But another thing that very interestingly came out when we were talking to these clinician groups is they fairly quickly in many cases, veered away from talking about the patient’s problems to talking about their own problems with medications. So for example, we started talking about patient medications and then it got into, oh my God, we try to do medication reconciliation in my clinic and it’s really hard. And then the pharmacy is always calling me and I can’t ever figure out what the pharmacy, it’s actually dispensed to the patient.

Mike: And these are real problems and they’re not to be minimized at all. But it really drove home for me that even in a group of caring, dedicated, high-quality clinicians, that we are oftentimes so overwhelmed by our own challenges with making the health system work if there’s just less mental space for us to really attend to patients’ concerns.

Alex: So you just gave the docs an out. You just said that they’re so wrapped up and they do have real problems that there may not be space for them to attend to patients’ concerns. Is that the answer here that we shouldn’t put this on docs to uncover the deeper layer of what this means for their patients and their daily lives and their relationships and their relationship with their doctor, the relationship that they have with their own patient and instead put it on somebody else. I think you suggested in the paper maybe pharmacists or other staff members, clinical staff could take up this role. To what extent is it the physician’s or clinician’s responsibility?

Eric: Maybe we just need another line in our med rec notes saying what are the social emotional factors that you maybe having that do or do not result in you taking this medicine?

Mike: Right, if we just put that as a series of check boxes…

Alex: Check boxes! [laughter]

Mike: Solve the problem. [laughter]

Alex: Reminders [laughter]

Eric: Clickable boxes. [laughter]

Alex: Unable to prescribe. You have not yet checked the box about the social or emotional context of this medication. [laughter]

Mike: Right. I mean, we joke about it but I think that everything is of course gray and nothing is completely black or white. Yes, it would be great if all conditions could and would attend to this. I wish I did it better in my own practice, but it’s just really hard. We all have limited time. Everyone is telling clinicians to do more and more stuff and there’s just only so many minutes per visit. And so from a realistic, practical perspective, we should be encouraging this and supporting this. But I think if we just assume that it’s all on the doctors or the nurse practitioners and they’re the only ones responsible is just kind of fail.

Mike: So what we really need to do is take advantage of other people who have the time and have the skills and have the ability to access patients in meaningful ways to actually help to uncover this and then work collaboratively with the prescribing clinicians so that everything can be aligned. And one prime example of that is pharmacists. There was this great… an article I saw just yesterday that had a great quote and I’m going to try to remember it as best I can, but it’s something along the lines of imagine if pharmacists are kind of… imagine if you were setting up a series of nutritionists that were based in a supermarket and the nutritionist really wanted to help people eat better and healthier food.

Mike: But all the nutritionists were tasked with doing was putting food into people’s shopping carts. And that if the shoppers ask the nutritionist for guidance about what they can do to eat healthier and better the nutritionist said, “Sorry, I’m not paid to do that. I’m only paid to put money into shopping carts.” Now we take that to the pharmacy level. What are most people… their experience with pharmacy? They go to the pharmacy, the pharmacist give them their meds, maybe gives them a brief spiel about their side effects and then sends them on their way. And the pharmacists have the skills, they have the resources, they have the training to be able to do this, but they’re not being tasked with that because we don’t currently have our systems of care in a way that provides the financial structures or incentives or the systems that will allow that.

Mike: And it can be a non-health professional, it can be a patient navigator or it can be a nurse or it can be a whole bunch of different people. And I think we need to find creative ways of engaging different sorts of people to get at this information because it is critical for patient’s health and wellbeing, but we’re just not doing it well.

Francesca: I should add too that we did an interview and do focus groups with pharmacists. So a lot of what we’re talking about isn’t just our thinking about, oh yeah, pharmacists should do this. But they had really great feedback and in many ways are much more closely aligned with patient perspectives on what medication related problems were and then the physicians themselves in particular around communication. Some of the pharmacists talked about how… and these were pharmacists that were embedded in primary care clinics in some capacity. And so their role is maybe a little bit different than certain types of pharmacists in the healthcare system.

Francesca: But many of them told us how this patient will confide in them that they’re not taking their medications, but they won’t tell their doctor for various reasons. So that was pretty interesting.

Mike: Very much.

Eric: So given everything that you learned from doing this study, publishing this, are there things or take homes that as clinicians I should have in my mind as I see my next patient and I’m thinking about medication problems?

Alex: If you could wave a magic wand and you as a medical anthropologist or as a clinician researcher who’s in geriatrician who’s thought about this a great deal and get each doctor or pharmacist to ask one or two or three questions of each patient about their medications, are there key questions that they should think about asking in order to uncover this deeper layer as you put it of context around medication prescribing?

Francesca: You could ask them just an open ended question like we did, “Tell me about the problems you have with your medications.”

Alex: That’s great. So that was one of the questions that you asked in these interviews?

Francesca: Yes.

Mike: I mean, everything I’m about to say is completely not evidence-based because we had this comprehensive interview guide and we certainly didn’t test what are the three best questions to ask that are going to elicit the information most effectively. But some of the questions we might ask in addition to the open ended one are like, do you have any worries about any of your medications or are any of your medications affecting your ability to do the things you want to do, your day to day life? Or do you have any concerns or problems with your medications that affect your life and how you want to live and I would really be open and interested to hear about them? So just creating the space I think is really helpful.

Mike: One thing we actually struggled with in this study, and I don’t think we really found a great solution to it, is what the label is that we attached to this. Because when we say medication related problems, people think about what problems mean in different ways. Some people define problems very narrowly and then we went to medication related concerns and I don’t think we really hit on one word that captures it all. But when we think about this, I would just tend to shy away from maybe using the word problems exclusively and maybe very explicitly just really open it up using language that makes sure that the person who’s hearing that question understands that’s inclusive of a very broad range of their experience.

Alex: That’s great. Those are great questions. And hopefully the pharmacist… usually we don’t like to screen for problems that we can’t do anything about although there is use in just understanding your patient better and understanding what’s going on and the impact of the problems they’re having with medications in their daily lives. But you could imagine that if there’s an issue in the relationship that comes up and the pharmacist uncovers it and they communicate it out to the physician, the physician might be able to address that. Or if there are issues with affordability of medication, then the physician might be able to change to an alternative or generic, less expensive medication.

Francesca: I think you hit on a really important point is that communication and rapport and the patient-provider relationship is really important. So even if, well, okay, fine, you can’t do anything as a physician about X, Y or Z, even just having the opportunity to talk about that for a patient with their provider can be really helpful. And actually one of the things in the communication category that was identified actually as a medication related problem was communication with providers, that patient said actually conceptualizing communication as a problem related to their meds.

Eric: Now, I can’t remember, was it the food insecurity podcast that we did where people were actually more open to discuss issues the farther away they were from the physician?

Alex: Yeah.

Eric: So it’s opposite of what I thought, they’d be more-

Alex: Comfortable-

Eric: … comfortable…talking about their food decision, about food insecurity, but it was actually the front desk stuff.

Alex: The front desk stuff about food insecurity.

Eric: Do we have any idea with patients around medications? Is there a similar phenomenon, is this better to do upfront with some questionnaires by non-physicians and then thinking about problem focused solutions with the physicians? Thoughts on that?

Mike: The shorter answers I don’t think we know for sure, it certainly makes sense that the example that Francesca gave about patients would often confide things in their pharmacists that they wouldn’t feel comfortable sharing with their clinicians may be a good example of that and hints to this phenomenon. But who is the right person to ask, how far away is too far, will written questions work? I think these are really important things, but we haven’t really uncovered them. There have been work asking… There has been some research and other clinical work having people fill out questionnaires in the waiting room like are you having any side effects from your medicines? Things like that.

Mike: But again, those tend to be the more narrowly focused clinician centric ways of thinking about these medication-related issues. And so we need to explore other ways of getting the broader series of concerns. How you do that in a questionnaire might be hard, but it’s probably necessary to explore.

Eric: And what I really like about this paper kind of… because I always think about side effects of medications, but that’s only one component of these medication problems and concerns that you’re bringing up from financial issues, it’s impact on your daily life from biking to doing anything else. And if you had a way like the pros of a medication for cholesterol versus getting somebody exercising out on their bicycle, that’s a balance that you should probably be thinking about rather than you should stop biking and use this medication.

Mike: Right. And just to maybe riff off something we were saying before, so in that case of, should I take my statin because I’m having some muscle pains or nonspecific symptoms, maybe diarrhea or maybe my nose is running and the patient might attribute that to the statins. And if they don’t feel like they’ve got a trusting relationship with their clinician, they might say, “That’s a statin side effect. I’m not going to take the statin.” Or might take it and then worry about what it’s doing to their health and their body and their wellbeing.

Mike: But if there’s a way of building a trusting relationship between the patient and the clinician around the medication use as well as around everything else, then maybe that patient would maybe have more trust in the clinician that when the clinician explains well, that running nose probably isn’t a statin side effect, and so let’s do these other things. So the patient feels like they’re being listened to and taken care of that actually can help to resolve the medication related to problem that the patient is feeling.

Alex: Mike… oh, do you have a question, Eric?

Eric: No, go ahead.

Alex: Mike, let’s say we’ve uncovered a number of important issues here on this podcast. Who is the best person to ask these questions? What questions should be asked? What questions are most effective at uncovering these sorts of issues? And then what can we do about it? What can clinicians do as a result, if that you are a US physician interested in studying these medication related problems or deprescribing and you are a researcher, is there anything that you could do to study this issue further?

Mike: Thank you for throwing this. Such a softball question, Alex.

Alex: You don’t have to be… do you have to be a physician to study this?

Mike: No. So you’re in good luck because we have recently formed something called the US Deprescribing Research Network, which is a network of people who are doing research in topics related to deprescribing as well as patients who are consumers of research on deprescribing, people who are consumers of deprescribing research. That can include the patients who are taking the medicines. That can include health systems. It can include anything, professional societies or anything in between.

Mike: And long with Cynthia Boyd at Johns Hopkins, she and I are co-leading this network. And the real idea is to bring a whole bunch of people together from all sorts of specialties, medicine, pharmacy, nursing, as well as stakeholders outside of medicine, patients, health systems, professional societies, and bring them all together around the table to figure out how we can actually research deprescribing in a way that’s going to move the dial to improve the research and then to actually bring interventions into reality that are actually going to improve patient outcomes and do so in a way that’s actually responsive to the needs of the people who are going to be using this information and intervention.

Alex: And are there any upcoming opportunities related to this network that our listeners should know about?

Mike: Funny you should ask. So there are two upcoming opportunities or several actually. So one is we have a call for pilot awards of up to $60,000 in funds to catalyze investigator initiated research projects around deprescribing.

Alex: When are those due?

Mike: Those are due on March 9th and there’s a letter of intent that’s due in early February as well. But the letter of intent is optional.

Alex: This podcast may come out too late for that opportunity.

Eric: Oh, we’ll see.

Alex: We’ll see.

Mike: All right. Well, it’s going to be annual, so if you miss it this year, get onto it next year. There’s also a junior investigator intensive which will be an annual thing. This year on 2020, the applications are due March 1st. And that’s providing resources for junior investigators in an intensive way to promote their research in deprescribing. But everyone is invited to attend our annual meeting, which is May 6th in Long Beach, California, which is adjacent to the American Geriatric Society Annual Meeting. And it’s really open to anyone who is interested in this research, either if you’re doing it or want to do it or are a consumer of this research.

Mike: And if you go to our webpage, deprescribingresearch.org, all the information is there.

Eric: I’m guessing that there’s not a lot of pharma booths at your deprescribing national meeting.

Mike: We were thinking about that and we were thinking maybe one firm would have a booth about how to deprescribe their competitors’ products. [laughter]

Alex: Unless there’s a medication that can prescribe that, we’ll deprescribe other medicines. [laughter] Well, any other things that you guys want to talk about before we end here?

Francesca: I just have to say that, Mike mentioned that working with an anthropologist brought him insight that he wouldn’t otherwise have. And likewise, I think from my end working with Mike and someone who thinks a lot about medications and deprescribing and as a geriatrician, I think it was a great collaboration. And as far as the paper goes, I think it’s a paper that neither one of us would have actually written on our own. And in that ways, it was great.

Mike: Yep. And this is a good example of teamwork as some of the things we’re trying to do with our deprescribing Network. We realized that physicians don’t have all the answers, pharmacists don’t have all the answers. Stakeholders don’t have all the answers, much less anthropologists or anyone else. But if we can bring people together across disciplines and across areas of expertise and perspective, then that’s really where we shine.

Alex: And I love the way that you start this paper saying, we have all these models, they’re all physician centric. They haven’t really gotten very far. We’re just beating our heads against the wall. Let’s go back to ground zero and start over again from a basic fundamental level and build theory from the lived experience of people, of the older adults who are taking these medications. And that’s where anthropology really shines when you’re starting from the ground up, what is going on here?

Mike: Yeah, exactly. I just want to acknowledge that we are not the first people who have ever thought about this.

Francesca: No.

Mike: There are other people who have been involved in this work and we must acknowledge. A debt of gratitude to the researchers who have come before us and hopefully will come after us.

Eric: Great. And with that, I really want to thank you for joining us on this podcast…

Alex: Thank you, Mike. Thanks Francesca.

Francesca: Thank you.

Eric: … but before we end, can we get Gerry Anders back here?

Alex: And everybody singing in the chorus.

Eric: Yeah. Even our listeners.

Alex: (singing)

Francesca: (singing)

Alex: It’s great.

Eric: I love it.

Alex: Mary Poppins.

Eric: With that, again, big thank you for joining us today. And thank you all our listeners for supporting GeriPal.

Alex: Thank you to Archstone Foundation. Thank you, Mike. Thank you, Francesca.

Mike: Thank you.

Francesca: Thank you both.

Eric: Goodbye.

Alex: Until next time, thanks. Bye.