In this week’s GeriPal Podcast, sponsored also by the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, we talk with Tom Gill, MD, Professor of Medicine at Yale.

With guest co-host Dan Matlock, MD, from the University of Colorado, we talk with Tom about his recent JAGS publication on the relationship between distressing symptoms, disability, and hospice enrollment. Tom conducted this study in a long running cohort of older adults that has made a number of outstanding contributions to the GeriPal literature (see links).

Major points:

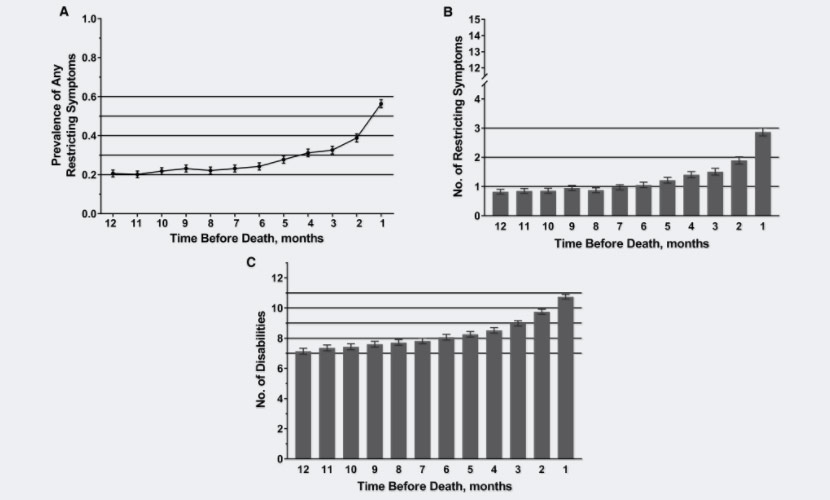

- Restricting symptoms start 6 months before death, but most folks didn’t enroll in hospice until 2 weeks before death

- Disability increased markedly over the last months of life, and precipitated hospice use, but most hospice and palliative care programs are not set up to help with a persons daily needs. There’s a mismatch between the need for daily assistance and the hospice and palliative care services offered.

Tom’s song request? Stairway to Heaven. This podcast was recorded at the recent Beeson meeting, an aging research meeting, near Albuquerque, New Mexico. At the end, you hear about 30-40 of us singing the end of Stairway around a campfire.

As in singing, “And as we wind on down the road…:”

Nailed it!

by:Alex Smith @AlexSmithMD

Links:

Alex: Welcome to the GeriPal Podcast, this is Alex Smith, and we have a special co-host with us today. We’re coming to you from the Beeson meeting in Albuquerque, New Mexico, and we’re joined today by Dan Mattlock, who is an Associate Professor at the University of Colorado. And welcome to the GeriPal Podcast as a co-host today, Dan.

Dan: Thank you very much, I’m excited to be here.

Alex: Terrific. And we have a special guest with us today at the Beeson Meeting. Beeson, for those of you who don’t know, is a geriatrics and aging-focused research meeting of clinicians, and this year it’s at a really fancy-schmancy nice resort near Albuquerque. And we’re joined today by Tom Gill, who is Professor of Medicine at the Yale School of Medicine, and an extremely well-known geriatrician researcher. Welcome to the GeriPal podcast.

Tom: Thank you, Alex. I’m looking forward to our discussion.

Alex: Terrific. So, we usually start out with a song request. What would you like us to perform?

Tom: How about ‘Stairway to Heaven?’

Alex: A terrific choice. We will give it our best shot.

Alex sings “Stairway to Heaven” by Led Zeppelin (Jimmy Page and Robert Plant).

So this is a podcast in a series of podcasts we’re doing between Journal of The American Geriatric Society and GeriPal. And today we’re going to talk about an article that is in early view on the JAGS website. And this is an article about restricting symptoms, disability, and hospice use from a long-standing cohort study that Tom has been running.

Do you want to tell us a little bit about … Just to set it up for our audience, and mostly clinicians, why this study is important? What clinical question are you addressing here?

Tom: Yeah, we know that the use of hospice is … Or, it’s underutilized in a few ways. One is, a minority of older persons, or persons in general will take advantage of the hospice benefit. And second, length of stays in hospice are extraordinarily short. And, so from our perspective, it’s a wonderful resource that’s been underutilized.

Alex: Terrific. And could you tell us a little bit about the cohort in which you study this issue?

Tom: We assembled a cohort back in 1998 of 754 persons seventy or older living in the greater New Haven community. They were all living in the community, and they were all non-disabled. And we were interested in primarily trying to determine the mechanisms underlying the onset of new disability and functional decline over time. It was supposed to be a two, and then a three year study, but we’ve continued to follow this cohort for now twenty years, interviewing them every month.

Alex: Incredible study, and a number of important publications related right at the geriatrics/palliative care interface have come out of this. Audience members may be familiar with the study in the New England Journal about trajectories of disability towards the end of life, and Sarwat Chaudhry published a paper about restricting symptoms, and sort of delved into which specifics symptoms change in frequency towards the end of life.

Dan: Yeah, that’s one of my questions from reading this. So, what is a restricting symptom, and how is that different from disability?

Tom: Sure. Every month we asked the participants two questions; Whether they’ve cut back on their usual activities because of an illness, injury, or other problem, or whether they’ve had to spend at least a half a day in bed because of an illness, injury, or other problem. And the reason for those questions was because that was going to be our mechanism to identify bad things that happened that didn’t lead to a hospitalization.

This was the precipitating events project. We were interested in identifying the events that precipitate disability. Our prior work had focused almost exclusively on hospitalizations, but the majority of persons who became newly disabled were not hospitalized. So we thought there must be other bad things that are happening. So restricted activity was our mechanism to identify less severe events.

And then we were also interested in determining the reason for restricting activity. So, if someone said yes to either of those two questions, we asked a series of questions about specific symptoms, and for this study, we focused on fifteen of those that varied from shortness of breath, to osteoarthritic pain, to fatigue, et cetera. And if they said yes to the symptom, we asked whether that caused them to have the restricted activity. So we linked the two.

Dan: And then how did you define, or how did you assess disability?

Alex: And how was that different?

Dan: And how was that different?

Tom: Right, so we … Every month during the same interviews we ask about thirteen different functional activities for basic ADLs. Bathing, dressing, walking, and transferring. And we asked them, at the present time, do you need help from another person to do those tasks? There are five IADLs and four mobility-related … Or, three other mobility-related items.

Alex: Terrific. And in this specific … This particular study, you looked at the relationship between hospice use amongst decedents, and there were about four hundred some odd decedents, and I think about 40% of them ended up using hospice. And you looked at the relationship between restricting symptoms, disability, and when they enrolled in hospice. Is that …

Tom: So, the supposition was that there would be either no relationship between restricting symptoms and the use of hospice, or disability and the use of hospice, in part, again based on what we know of hospice, that it’s generally underutilized. And we thought that folks were taking a disease-specific approach to the use of hospice, as opposed to focusing either on function, or on these restricting or troublesome symptoms.

So that was the underlying kind of premise, and we thought, “well, if doctors aren’t putting much stock in these very important features, that might be an explanation in why hospice is not used to the extent that it might otherwise be.

Alex: And can you tell us what you found?

Tom: So, contrary to what we found, or what we thought, there was actually a fairly strong relationship between the occurrence of restricting symptoms in any one month, and the use of hospice. Restricting symptoms increased the use of hospice by 62% in any one month.

The relationship for each additional restricting symptom, I believe the increase was about 9%. And for disability, for each additional disabled activity was around 10 or 11%.

But, that has to be interpreted in the context of the median length of stay in hospice, which was only twelve days. So there were strong relationships between these exposures and the use of hospice, but hospice was used in more than half the participants in less than two weeks. So it was fairly late in the game.

Alex: And I think clinically, you know we’re all clinicians, I think it makes sense intuitively that as somebody’s symptoms progress, they’re more likely to enroll in hospice. I remember early on in my clinical training in palliative medicine, David John Syracuse, one of my mentors, said, “you can ask patients, what is your body telling you?” And when your body is hurting and suffering, then that’s often when they sort of make a change in their goals of care, and there’s a shift and they might be more open to hospice.

Does that ring true with your clinical experience, Dan?

Dan: Oh, yeah, completely. I think … And that actually was another question I have. So, did you … If you started this in 1998, palliative care wasn’t very pervasive at that time. Do you see any changes over time, or do you have enough people to look at that?

Tom: I think we did look at time as an interaction, and we probably were not powered to evaluate that. There was not an interaction for time. The hospice movement was still in place in the late 1990’s. Palliative care as a field wasn’t, but hospice care was. The cohorts aged, and I think the use of hospice is increased in part because of the aging of our underlying cohort.

Now, one thing I didn’t mention early … I mean, we looked every month for the last year of life for the prevalence and the severity of the symptoms and the disability, and they were relatively flat for the symptoms until about six months prior to death. And then the prevalence of restricting symptoms started increasing, and the severity of restricting symptoms increased. But it was really not until the last month or so in which hospice use started being used … Hospice being used.

Alex: So, this twelve day thing, I’ve heard from hospices, this is something that they really would like to see increase. They would love to offer hospice for longer periods of time for folks. After looking at this, do you have thoughts on ways hospices could increase the number of days they are able to provide for people?

Tom: Well, I think this is where that palliative care field can … If folks would avail themselves more to palliative care, not to hospice … Because earlier in the last year of life, they’re not ready to make a decision for hospice. But, I think they might make a decision for hospice sooner if they’re already being cared for by a palliative care clinician.

And those discussions, they need to start earlier. The decision to opt for hospice is often not made overnight. It’s a decision that needs to incubate, and perhaps be revisited over the course of many weeks and sometimes months. So as these symptoms increase, and these are all folks that had clearly terminal conditions, about … A proportion had cancer, and another proportion had organ failure, and dementia. And frailty was actually the largest group. But there weren’t that many differences within those conditions. So the results were fairly robust.

But I think earlier discussions in the context of palliative care I think might improve some of those statistics, and I’m not sure if that’s where the field is heading.

Alex: Hopefully that’s where the field is heading. I would say, that’s the idea that we get people enrolled in palliative care from the time of diagnosis with serious illness. It’s a little bit trickier in many of the older adults that we care for who don’t have a clearly terminal condition, who have that frailty, who have multiple chronic conditions, who don’t have a clearly terminal illness, who nonetheless are nearing the end of their lives.

Tom: But, I mean, palliative care need not be limited to the end of life, and again that’s where the symptoms came in. The prevalence of symptoms, of these restricting symptoms, I believe was 20% a year prior to death, and then increased quite significantly in the last six months of life.

So, even if it’s not obvious that someone is in that last phase of life, they clearly have a large burden of symptoms, and it would be I think to the patient’s advantage to have input from clinicians who have expertise in palliative care. Because that extra layer of care in addition to their usual care I think could be quite beneficial.

Alex: And we’ll have links to the article itself, and the terrific figures, because I think the figures really tell the story. And we’re describing about sort of acceleration of symptoms and disability, and I want to touch on the disability point because I think that’s important too. Showing that disability increases before somebody enrolls in hospice. And that … Is hospice … How well does hospice and palliative care provide for the needs of disabled older adults?

I know your study didn’t address that directly, but it’s certainly something that’s worth commenting on.

Tom: And I believe that one of our prior … We have a couple prior papers looking at hospice in the last year of life. Descriptively, looking at symptoms before and after the start of hospice, and the restricting symptoms are reduced after the start of hospice. And … Difficult to make causal association, but the data were fairly compelling, in terms of the value added to hospice. That’s what you would hope to expect.

The same is not necessarily for disability, at least the way we defined it, because it’s the need for personal assistance. And that need is likely going to be maintained through the end of life.

Dan: Yeah, your question is a good one. I mean, hospice is great, but it can’t do everything for everybody, and that’s kind of a tough thing for people to realize sometimes when they’re sick. And disability … If somebody’s home with their family with disability, they might not be getting everything they need in hospice.

Alex: Yeah, the major needs, palliative needs, moving away further from the end of life to people living with serious illness, and the older adult patients that we care for are often needs for daily assistance type care. And hospice doesn’t provide that benefit. Palliative care doesn’t provide that benefit. I think it’s an argument for restricting of the healthcare system to better meet the needs of older adults who are living with serious illness, which includes not just symptoms, but also disability.

The systems were mostly designed around fifty year olds with cancer, but the way demographics are changing in this country, we really need to shift the symptoms to meet the needs of older adults we’re caring for.

Anything else you want to say about this particular study, or point out to our audience? Any take home points that we haven’t covered yet?

Tom: Well, it’s just … These are questions that we’re addressing now that weren’t on the radar screen twenty years ago. For a variety of reasons, this was not designed to be a study of death and dying, but because we followed this cohort for such a long duration of time, and the vast majority of our participants have died. And it is just fortuitous that we had collected all this data, and now can start addressing some of these questions. And we would welcome ideas from the palliative care community about other questions that these data potentially can help address, because I think they’re quite unique.

We’ve completed almost 90,000 phone interviews over the past twenty years, and have had less than 5% attrition in this cohort for reasons other than death. And we go out to the home every eighteen months to do a very comprehensive evaluation. Evaluating cognition, and depressive symptoms, and physical performance, and things of that nature. So we often say we know these participants better than they know themselves.

Dan: I’ve got to say, that’s one of the coolest things about this, is this cohort you’ve followed for twenty years. So, if four hundred people of them have died, and you enrolled seventy year olds twenty years ago, that means you must have a cohort of three hundred ninety year olds you’re following. Is that true?

Tom: Well, for this study, because we needed to link the data to CMS to identify the hospice cases, I believe they were cases through 2014. So we only have, I think, sixty or so participants who have not yet died. And we are continuing to interview them, and we’re planning to interview them all until they’ve died.

The other interesting footnote here is this project was my Beeson project from 1997. I had the good fortune of combining the Beeson winner Robert Wood Johnson Generalist Award, and this got the cohort assembled. And then we exhausted the money, and I’m one of the few Beeson scholars that spent the money before the three years were out. It was a very wise investment. And then we had the good fortune of getting an NIH grant that allowed us to continue to follow up, although when I applied for that NIH grant, we had enrolled five hundred participants and had followed them for about six months with monthly interviews. The biggest criticism, and it wasn’t funded the first time around, was, we don’t believe you can do this.

So we resubmitted the grant the next possible cycle, and we now had follow up for about thirteen months. And 99% completion rate for these interviews. Very little attrition rate. We says, “do you believe us now?” So we were funded on that second go-around.

But there were a few times during this twenty years in which the funds were almost on fumes, and we were able to patch things together and allow us to continue. And these participants were grateful for, because we were learning a lot about the course of disability, and a lot now about what’s happening in the last phase of life.

Alex: Well, that’s terrific. Thank you so much for joining us. We will again have links to the article itself, and is there a website for the cohort?

Tom: It’s off our … The Pepper Center, the Yale Pepper Center site. There’ll be a little blurb on the pep study.

Alex: Terrific. We’ll have that link as well. Thank you so much for joining as co-host, Dan.

Dan: Oh, it was my pleasure. This was fun.

Alex: And thank you so much for joining this JAGS/GeriPal podcast, Tom.

Tom: Thank you, Alex.

Alex: Alright, let’s end with a little ‘Stairway to Heaven.’

Alex sings “Stairway to Heaven” by Led Zeppelin (Jimmy Page and Robert Plant).