Growth in inpatient palliative care over the last decade has been remarkable. A study published this monthshowed that in 1998 only 15% of hospitals with more than 50 beds had an inpatient palliative care program. That numbers is now 67% nationally. While this is great news, one can’t help to think that the majority of patients facing a serious illness, such as advanced cancer, are not in the hospital. A study published this week in JPM by Colin Scibetta Colin, Kathleen Kerr, Joseph Mcguire, and Mike Rabow gives us more weight when advocating for improved early access to palliative care through the delivery of outpatient consultations.

What they did

The authors included patients with solid tumors who died between January 2010 and May 2012 and who received care in the final 6 months of life at the UCSF Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center. They used claims data to identify patients who had involvement by either the outpatient or inpatient palliative care service. The categorized these indivudals as either having:

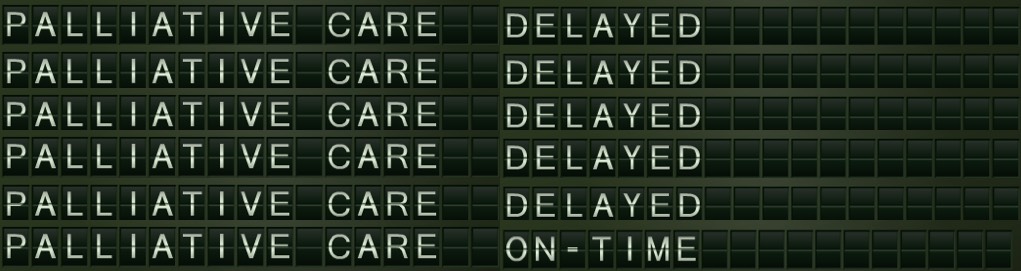

- early palliative care: the initial palliative care contact occurred more than 90 days before death

- late palliative care: the initial contact was within the last 90 days of life.

The outcomes of interest included NQF EOL quality metrics to assess differences in utilization (ICU days in final month of life and multiple emergency department visits in the final month of life) as well as death in the acute care setting, 30-day mortality, death within 3 days of hospital discharge, and inpatient admissions in the last month of life. They also looked at direct cost of care to the health system for care delivered in the inpatient and outpatient settings in the 6 months preceding death.

What they found

Among the 297 decidents included in this study, 93 (31.5%) had early palliative care, while 204 (22.1%) had late-palliative care. Both the early and late group looked the same, except that patients with urologic or gynecologic cancers were more likely to have early palliative care than those with other cancers. Most of the early palliative care was attributed to being seen as an outpatient, while late palliative care was mostly delivered in the hospital, despite being seen in an outpatient oncology clinic during the 91–180 days prior to death.

Utilization – earlier is better

Compared to the later palliative care group, those who got early palliative care had:

- lower rates of inpatient admissions in the last 30 days of life (33% versus 66%)

- lower rates of ICU use in last month of life (5% versus 20%)

- fewer emergency department visits in the last month of life (34% versus 54%)

- a lower rate of inpatient death (15% versus 34%)

- fewer deaths within three days of hospital discharge (16% versus 39%)

- lower 30-day mortality rates post hospital admission (33% versus 66%)

Cost of care – earlier is better

Compared to patients who had late palliative care, the early palliative care group had significantly less direct costs ($32,095/patient versus $37,293/patient). This was largely due to a significant decrease in inpatient direct costs (average of $19,067/patient versus $25,754/patient, p = 0.006), as the direct costs for outpatient care in the final 6 months of life were not statistically significantly different (average of $13,040/patient versus $11,549/patient), p = 0.85).

Take Home Points

I think there are three main take home points from this study:

1) If you want to significantly improve early access to palliative care, you must deliver this care outside of the hospital setting. We’ve seen this with our own data at our medical center. The second we opened up a palliative care clinic nearly a decade ago, our time from consult to death increased from a little less to a month to now over half a year.

2) If you improve early access to palliative care by developing an outpatient clinic, you will see a drop in inpatient deaths. Again, we’ve seen this in our own medical center. The drop in inpatient deaths though creates problems if quality metrics are only measuring what happens to inpatient deaths (the easiest deaths to capture). For high quality metrics, all deaths need to be captured, something that is difficult in a fragmented health care system.

3) The delivery of high quality of care can also be cost-effective care. This study further adds to the growing list of studies that palliative care can not only can improve the quality of care for patients with serious illness, but can do it in a way that also reduces total health care costs.

by: Eric Widera (@ewidera)