by: Bree Johnston

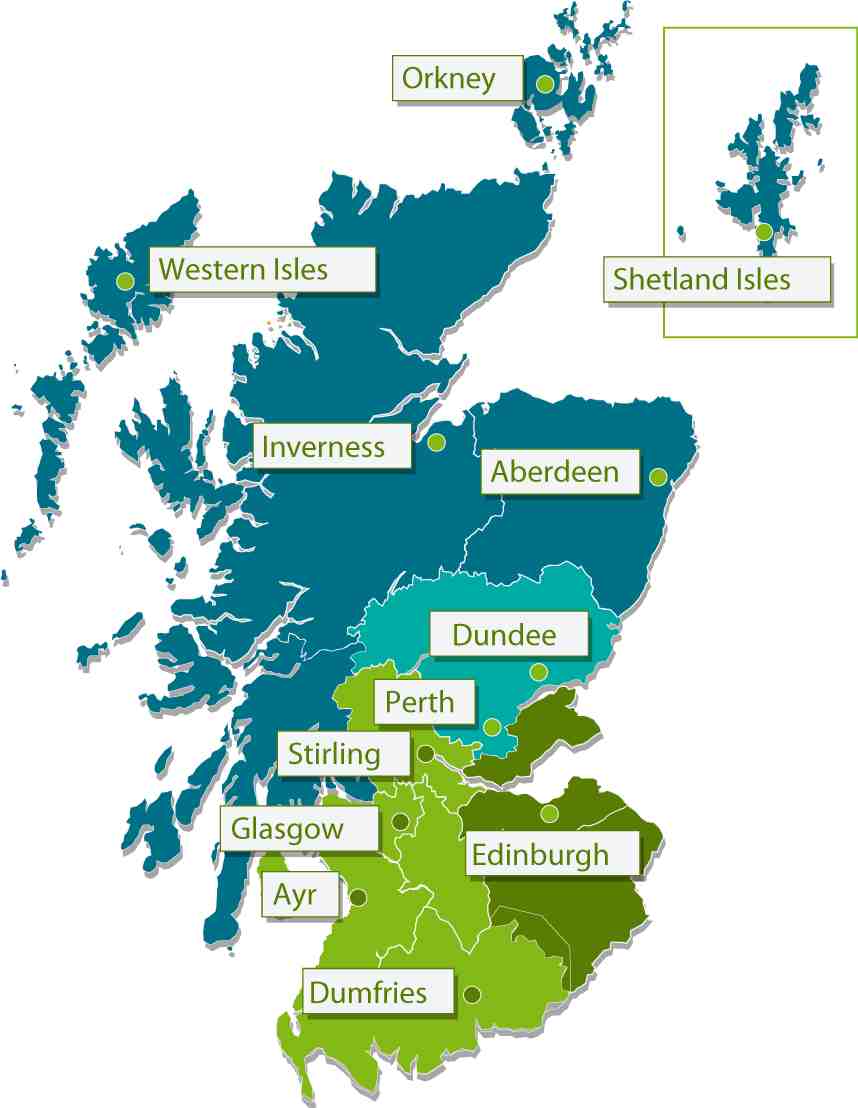

For the past two months (started July 2010) I have been in Scotland working in variousgeriatrics and palliative care settings. Most of my geriatrics (as opposed to palliative care) work has been at the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh, Liberton Hospital in Edinburgh, and Western General Hospital in Edinburgh. My many hosts here have been extremely lovely and generous with their time (and tea) and I can’t thank them enough.

Here are some thoughts on geriatrics, presented in no particular order. Some of what I will say here is a repeat of my earlier GeriPal blog on palliative care.

NHS Scotland

Although funded centrally from national taxation, NHS services in England, Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales are managed separately and have some differences in structure. Despite the minor differences, the NHS is similar in most respects throughout the UK and continues to be considered a single, unified system. One interesting difference between the NHS in Scotland and England is that there is much less of a parallel private health care system in Scotland than in England. Some of my hosts attribute that to a less individualistic culture in Scotland than England that may be partly rooted in the Scottish Calvinism.

The global recession is hitting the UK hard, and there is widespread concern that the NHS funding will be severely curtailed in the years to come. The change in government at 10 Downing Street is unlikely to improve the commitment to NHS funding, either. Let’s stop on this vein before I get too political…

Training

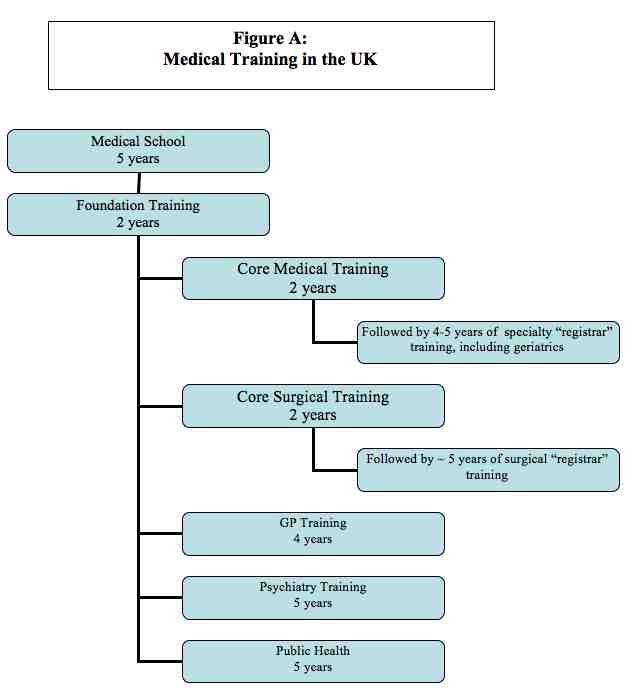

Training in the UK is quite different than in the United States. Perhaps the most notable difference being that medical training begins directly after secondary school (when I queried one colleague about whether they felt they missed out on a well rounded education, he wryly replied that our US liberal arts education didn’t produce doctors that seemed more humane, as evidenced by “our” tolerance of millions of people with no health insurance). Since the training is incredibly confusing to me, I have depicted it in figure A below, thanks to my colleague Jennifer Mullen. I can’t guarantee that it is completely accurate, but it is probably close.

Medical school in Scotland is 5 years. All students receive some exposure to geriatrics and palliative care, although the experience varies between medical schools. At the University of Edinburgh, students have a one month rotation in geriatrics during their fifth (last) year. The course consists of two days of geriatric didactics, a one day introduction to palliative care, and three and a half weeks of clinical geriatrics, which is inpatient. Geriatric exposure in post-graduate medical education is variable. Scotland recently reformed its postgraduate medical education with The Modernising Medical Career (MMC) program. Following medical school, physicians enter a two-year foundation program that includes new disciplines such as team-work and patient safety, in addition to more traditional rotations. The training is competency based. Although many physicians will have a four month rotation through geriatrics (Medicine of Elderly or MOE) or palliative care during their foundation years, not all do.

Foundation Programs are followed by progressive specialty or general practice training programs. Specialists in hospital medicine will all rotate through MOE wards; some, GPs will, as well. Geriatrics is a fairly common specialty (although I cannot give you figures at this time), and there is also a combined general medicine/geriatrics pathway. Geriatrics and palliative care are quite separate specialties here. Geriatricians in training do rotate through palliative care, but in general, there seems to be much less overlap between the two fields than in the US.

The Practice of Geriatrics

Geriatrics can only be understood within the broader context of primary care in the UK. General practitioners (GPs) are the backbone of the NHS, providing almost all primary care, and accounting for over half of all physicians. All GPs make home visits, and most make nursing home visits, as well, which provides terrific continuity for patients.

In Scotland, as the rest of the UK, geriatrics is primarily an inpatient specialty. I believe that the vast majority, if not all hospitals have MOE wards that are staffed by geriatricians. Geriatricians, not neurologists, also care for most stroke patients and staff stroke units. “Orthogeriatrics” is another common branch of geriatric medicine here in the UK. There is at least one hospital (Liberton in Edinburgh) that is entirely devoted to MOE. Liberton has acute care and rehab wards, but tends to accept older patients of lower acuity, as it lacks some services such as ICU care and advanced imaging services.

Some geriatricians also have clinics, but the clinics are entirely consultative, with GPs always assuming the primary care role. Geriatricians also do very few home visits (although they used to be common) and provide little nursing home care; those areas are the purview of GPs. Patients who need assessment but do not require an inpatient stay are seen in geriatric day hospitals (I am not attending a day hospital until next week, so can tell you more about them then).

Services for Elders

“Social care” is funded separately from medical care, paying for nonskilled community home care (home health aide in US terms) and nursing home care (I believe that is not the case in England).

Elders who need unskilled services at home get referred for “packages of care”, generally from 1-4 times daily. For patients over 65, the services are generally free as long as the service if for personal care; IADL assistance may be charged based on means.

Nursing home care is not free, and is paid for based on means. Because social care is relatively underfunded in Scotland, and because it is paid for separately from medical care, there is often frustration on the medical side of the long waits that patients may experience. Inpatient stays on MOE units are long by American standards, somewhere in the range of 20 days, and much of the length of stay is due to waits for nursing home beds.

Skilled home care is provided by district nurses in close collaboration with GPs. Other skilled home services such as PT/OT are also available.

Again, there is widespread concern that social care funding will be cut even further in the years to come, due to the recession and the more conservative government at 10 Downing Street.

Inpatient Practice

The organization of inpatient care is interesting. A&E (accidents and emergency) is the emergency department. For some years, there has been an A&E target that “ no patient will wait more than 4 hours from arrival to admission, discharge or transfer for accident and emergency treatment”. Although this provision has been controversial and is probably being dropped in England, it still drives much of the organization of acute care in Scotland, and it appears that the four hour target is met in > 98% of the time.

After an initial assessment in A&E, a patient is either discharged home or sent to the “combined assessment area”(CAA) unit for further evaluation and triage. In general, patients will not stay in CAA for longer than 48 hours. Of interest, PT and OT are available in CAA, so that patients needing those services can be assessed and treated quickly.

Geriatrics at the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh employs nurses (ECAT – evaluation combined assessment team) to assess all patients over age 65 who are in CAA. The nurses will assess the patient’s medical diagnoses, functional status, cognition, and social context, and then determine if the patient is appropriate for a MOE inpatient unit, MOE hospital (such as Liberton), discharge home with a package of care, or other disposition. The ECAT nurses have protocols that help guide them in the appropriateness of MOE admissions. In general, MOE admissions tend to have multiple morbidities AND functional impairment; elders with a single disease and no functional deficits may go to a cardiology, respiratory, or other unit, depending on the underlying pathology. The ECAT nurses work closely with the geriatrics consultants to determine which patients are most appropriate for the MOE unit. Older patients who initially go to other specialty units are often followed by the ECAT nurses, who determine if they become appropriate for an MOE Unit at a later time.

It was exciting to see that (almost) all patients over age 65 seen in CAA get mental status testing (10 question abbreviated mental test score, including such wonderfully British questions as “what is the Queen’s name?” and “when did the First World War begin?”. Also, it seemed routine to try to determine if patients were delirious or demented, and it seems that the ECAT nurse presence served to promote the culture of thinking about delirium, dementia, and function in the CAA.

Dementia and Delirium

NHS establishes HEAT (Health, well being and Care Targets) Targets that are goals for quality improvement that will result in bonuses, if achieved. Based on estimates of the prevalence of dementia in Scotland, the Scottish NHS established numerical goals for GP diagnosis and early management of dementia, to be fully met 2011. Some of the goals of the HEAT dementia target include:

- Recording of treatment for cognitive impairment;

- Ensuring service users who develop behavioural or psychological dementia symptoms receive an intervention matched to their needs; and

- Ensuring that advance care planning is in place in relation to end of life care.

More information is available at:

http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Topics/Health/health/mental-health/servicespolicy/DFMH/dementia

From data presented on the NHS website and personal communications, it appears that the HEAT dementia initiative has been successful in increasing diagnosis of dementia by GPs.

Alasdair MacLullich, Professor of Geriatric Medicine at the University of Edinburgh and the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh (and my gracious professional host here in Edinburgh) is doing exciting work on delirium, both in the areas of pathophysiology and identification. Among other things, he chairs the Delirium and Dementia Implementation Group (DDIG), which aims to improve the care of delirium and dementia through (a) higher rates of formal diagnosis, (b) better inpatient management, including prevention of delirium in vulnerable patients, and (c) appropriate follow-up after discharge. Dr. MacLullich is piloting a delirium/dementia assessment tool that I am hoping to trial in the US. Dr. MacLullich is also working with the European Delirium Association, which is doing outstanding research on delirium pathophysiology, treatment, and prevention.

There is much more to say and I realize that this blog has left many gaps and unanswered questions, but hopefully it gives a bit of an overview. I am happy to blog more on any topic that GeriPal readers might be interested in hearing more about. I also welcome any corrections from people who know the system better than I do!

Related Websites

http://www.europeandeliriumassociation.com/

http://www.bgs-scotland.org.uk/

http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Topics/Health/health/mental-health/servicespolicy/DFMH/dementia