Do We Ask for Permission to Treat First? Or Treat first & Ask Questions Later?

As we are educated on the ethical & financial concerns surrounding end-of-life care, we are informed by

Institute of Medicine that end-of-life care is broken and accounts for $170 billion in annual

spending (1). This projection will exceed $350 billion in less than 5 years. To better align

patient wishes, living wills & POLST (Physicians Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment) are

necessary documents and processes. Whether you like them or not they are here to stay are we

need to assure provider competency. Additionally, Medicare now reimburses for advance care

planning conversations in the office or via telemedicine. In the past, Physicians have tried

to embrace living wills and more recently, the POLST paradigm has emerged to the national

forefront. POLST & POLST-like processes have grown rapidly, which has outpaced the ability

of states to educate to ensure the safe & effective utilization of this process. Both living

wills & POLST have limitations but are good documents with many benefits and are very much

required to allow patients to preserve their autonomy (2,3). How these documents are applied

by others, in clinical situations, such as critical illness, has led to the unintended

consequences of both “over” & “under” resuscitation. By way of their success, we have

essentially introduced a new patient safety risk which has no quality oversight. As a

result, we now must recognize these risks & act to protect patient wishes and outcomes.

Living wills require interpretation. POLST does not and is an immediately activated

medical order set. So can we correctly interpret living wills and can we trust the POLST

becomes a question. Most living wills are created by attorneys years in advance prior to the

onset of medical conditions. The POLST are completed by other providers (ex. Social Workers

or admission nurses) & signed by physicians who may or may not have been involved in the

conversation. So, how do frontline physicians (such as Pre-hospital, Emergency Medicine,

Trauma and Hospitalist physicians) interpret these during a brief interaction? Specifically,

Emergency Medicine physicians do not know these patients or families & have no established

trusts or report, yet, within seconds, are expected to understand the patient’s wishes to

either accept or decline life-saving interventions based upon a form. Of what is often

documented, the “Full Code” appears understood. However, with a do not resuscitate order,

things are less clear. Further, with POLST, there are many combinations of treatment

options, which make the water muddier.

The TRIAD (The Realistic Interpretation

of Advance Directives) studies have questioned whether or not providers understand what to do

with Living wills, do not resuscitate & POLST orders. It questions whether we are trampling

on patient wishes to better control costs. We need to figure out who is better off with a

living will vs. a POLST. We need to set quality standards & abide by them universally for

both the living will & POLST. More importantly we need to standardize Goals of Care

conversations, so they are balanced & can accurately predict the patient’s wishes. That

information then requires the ability to be conveyed to a totally different & disconnected

medical provider in a safe & effective manner that ensures no patient safety risk to the

actual patient.

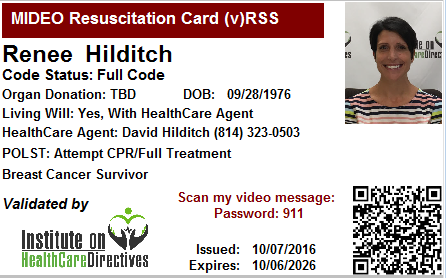

Volandes, Wilson & El-Jawahri have performed pioneering work with

clinician to patient video. It has been shown that clinician to patient educational videos

can help patients make informed decisions about CPR (4,5,6). So, could we then utilize

patient to clinician video testimonials to help providers make informed medical decisions for

patients in a safe & effective manner? In March 2017, the Journal of Patient Safety

released the TRIAD VIII Study. This was a Multicenter Evaluation to Determine If Patient Video Testimonials Can Safely Help to Ensure Appropriate Critical vs. End of Life Care. From this work, we can now say that we can do things

better to ensure we get it right for patients. Figure 1 is just an example of how we can

bring patients back into the actual decision-making process.

With patient video clarification, we can now

hear from patients, in their voice and expressions, when they are critically ill & receive

their guidance rather than providers guessing after reviewing a form that may or may not have

been completed correctly. We know that forms when not fully completed lead to errors in

treatment(8). We know that POLST forms can be discordant with patient wishes (9).

Resuscitations are complex & physicians need to know what to do initially in the first

seconds to 15 minutes of an event. Furthermore, the physicians comfort in the process to

trust and act on what is documented is of paramount importance. Paper forms at present do

not do this well or provide the necessary level of assurance to Physicians. We still need

POLST & living wills but we also need to hear from the patients to clarify the patient’s

wishes. With emerging technologies, we also need to be able to incorporate patient to

clinician video in a safe & cost effective manner.

In conclusion, we have a safety

problem with living wills & POLST documents. TRIAD VIII presents an opportunity to do

better. The traditional treat first and ask questions later approach is already being

challenged by the development of malpractice litigation. To do what is right for patients,

we need to embrace both living wills & POLST & be sure we set quality standards for their

completion & understanding. We must also investigate patient to clinician video and

technologies to allow the clinicians to hear from the patient to accurately guide their

care.

References:

- Institute of Medicine. Dying in America: Improving Qualityand Honoring Individual Preferences Near the End of Life. National Academies of Sciences,

Engineering, Medicine. September 17, 2014. Available at:

http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/Reports/2014/Dying-In-America-Improving-Quality-and-

Honoring-Individual-Preferences-Near-the-End-of-Life.aspx. Accessed January 3, 2016.

- Nicholas LH, Langa KM, Iwashyna TJ, et al. Regional variation in the association betweenadvance directives and end-of-life Medicare expenditures. JAMA. 2011;306:1447-53.

- Fromme EK, Zive D, Schmidt TA, et al. Association between Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment for Scope of Treatment and in-hospital death in Oregon. J Am Geriatr

Soc. 2014;62:1246-51.

- Volandes AE, Paasche-Orlow MK, Mitchell SL, et al. Randomizedcontrolled trial of a video decision support tool for cardiopulmonary resuscitation decision

making in advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:380-6.

- Wilson ME, Krupa A, Hinds RF,et al. A video to improve patient and surrogate understanding of cardiopulmonary

resuscitation choices in the ICU: a randomizedcontrolled trial. Crit Care Med.

2015;43:621-9.

- El-Jawahri A, Paasche-Orlow MK, Matlock D, et al. Randomized, controlledtrialof an advance care planning video decision support tool for patients with advanced

heart failure. Circulation. 2016;134:52-60.

- Mirarchi FL, Cooney TE, Venkat A, et al.TRIAD VIII: Nationwide Multicenter Evaluation to Determine Whether Patient Video Testimonials

Can Safely Help Ensure Appropriate Critical Versus End-of-Life Care. J Patient Saf. 2017 Feb

14 [Epub ahead of print] PubMed PMID: 28198722.

- B Clemency et al. J Am Med Dir Assoc 18(1), 35-39. 2016 Sep 28. Decisions by Default: Incomplete and Contradictory MOLST in

Emergency Care.

- Hickman SE, Hammes BJ, Torke AM, Sudore RL, Sachs GA. The Quality ofPhysician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment Decisions: A Pilot Study. J Palliat Med. 2016

Nov 1 [Epub ahead of print].

Disclosures:

Ferdinando L. Mirarchi,

D.O. has disclosed that he is the Principal Investigator of the TRIAD research series. He

has an independent medical practice that focuses on advance care planning. He further

discloses that his patients receive an ID Card depicted in this publication.

Kate

Aberger MD, was a study site Principal Investigator for the TRIAD VIII study and has no

further disclosures.

by: Ferdinando L. Mirarchi and Kate Aberger