In a new study in JAGS, Matthew Growdon found that the average number of medications people with dementia took in the outpatient setting was eight, compared to 3 for people without dementia.

In another study in JAGS, Anna Parks found that among older adults with atrial fibrillation, less than 10% of disability could be explained by stroke over an almost 8 year time period. She also talked about the need for a new framework for anti-coagulation decisions for patients in the last 6 months of life, based on an article she authored in JAMA Internal Medicine with Ken Covinsky.

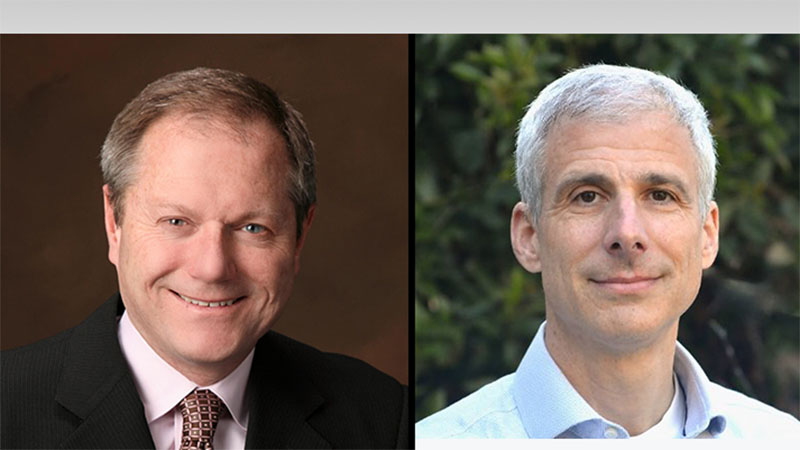

In today’s podcast we talk with Matthew and Anna, joined by co-author Mike Steinman, to talk about polypharmacy, deprescribing, where we are and what we need to do to stop this freight train of ever more medications for older adults and those living with serious illness.

We start by addressing the root cause of the problem. Clinicians want to “do something” to help their patients. And one thing we know how to do is prescribe. It’s much harder psychologically for clinicians to view deprescribing a medication as “doing something.” This attitude needs to change. It will take teamwork to get there, with robust involvement of pharmacists, and likely activating patients to advocate for themselves.

And Eric might have mentioned aducanumab a time or two…

-AlexSmithMD

Eric: Welcome to the GeriPal Podcast, this is Eric Widera.

Alex: This is Alex Smith.

Eric: And Alex, who do you have with us today?

Alex: Today we are delighted to welcome Anna Parks, who is an aging research fellow and a hematology fellow and is soon to be an assistant professor at the University of Utah. Welcome to the GeriPal podcast Anna.

Anna: Thank you. Thanks for having me.

Alex: We’re also delighted to welcome another aging research fellow and geriatrician Matthew Growdon who is also at UCSF currently. Welcome to the GeriPal podcast Matthew.

Matthew: It’s great to be here.

Alex: And were delighted to welcome back Mike Steinman who’s an Aducanumab lover. [laughter]

Mike: You’re giving me a bad rap… [laughter]

Alex: I shouldn’t say that – it’s not true. He’s a professor of Medicine at UCSF Co-PI of the USD prescribing research network, welcome back to the GeriPal podcast Mike.

Mike: Thanks Alex and Eric.

Eric: So this is kind of a polypharmacy, deep prescribing, super special. We’re going to be talking about a couple of papers that are linked to that subject but before we do, who has a song request for Alex?

Matthew: I guess I can speak for myself and Anna, we picked this week, Joni Mitchell’s Case of You. And this is a favorite song of both of ours and we also felt like if you really stretched your minds you could come up with some analogy to taking a lot of meds. [laughter]

Matthew: But we really just want to see Alex singing a perennial favorite.

Alex: Yeah, and it’s the 50th anniversary of the Blue album, Joni Mitchell’s Blue album. So appropriate. I won’t sound anything like Joni Mitchell but here we go.

Alex: (singing) “Just before our love got lost you said, I am as constant as a northern star and I said, “Constantly in the darkness. Where’s that at? I’ll be in the bar”. On the back of a cartoon coaster, in the blue TV screen light, I drew a map of Canada, Oh, Canada. With your face sketched on it twice, oh, you’re in my blood like holy wine. You taste so bitter and so sweet. Oh, I could drink a case of you, darling. And I’d still be on my feet, I’d still be on my feet.”

Eric: Excellent! Thank you Alex! So we usually start off these episodes on how you all got interested in this subject and we already had Mike Steinman on so I’m going to first turn it over to Anna. We’re going to be talking about two Jags papers that just came out, one Matthew did on polypharmacy in older adults and Anna did one on longterm functional outcomes in older adults with a-fib. I know you’re a hematology fellow too, how did you get interested, especially for older adults?

Anna: Sure. Honestly it came from clinical experiences and I think many listeners to the podcast have probably experienced this, where you have a patient in your practice who has a very good reason to be on blood thinners, maybe they’ve had a lot of problems with clotting but you also have seen the downstream effects and the way that it may uniquely affect older adults. So they have a lot of bleeding, they call a lot about nose bleeds and maybe they feel afraid to lift up their grandkids because they’re worried about bleeding. I felt like those experiences and voices are not well represented in the hematology world and in clinical trials. And so, I got interested in trying to better understand those experiences and then use those insights to improve the way that we manage that fine balance between clotting and bleeding. So atrial fibrillation is sort of a model condition in that way, but there’s a lot of them within hematology so that is my story.

Alex: Yeah, this is a big clinical issue, right. Anna or Mike, maybe you know off hand, there are a huge number of older adults who are eligible for anti-coagulation by guidelines, who just don’t take the medication. So they’re voting with their feet, and what we consider to be nuisance bleeding, to them may be a lot more than nuisance in terms of the impact in their lives.

Anna: Yeah exactly, it’s over 50 percent of patients. For a-fib for example, by clinical guidelines, which are really based heavily on chronologic age, which we know is an issue, should be taking anti-coagulation but they don’t and I think we can gain a lot of insight both from clinical practice and also talking to patients in trying to better understand their experience. And then through papers like Matthew’s and hopefully mine as well.

Eric: Well let’s do that, so I’m going to turn over to Matthew. Matthew how did you get interested in this? And then we’ll talk about Matthew’s paper, then Anna’s paper just thinking about particularly diving in to this anticoagulation topic. Because I know Anna also had a JAMA-IM editorial on it. So lot’s to cover. Matthew, how’d you get interested in this, polypharmacy?

Matthew: Yeah, I think similarly to Anna, for me a lot was born out of clinical experience and in particular, in training as a Geriatrician but also in internal medicine residency. And in my early years working as a Geriatrician I’ve just been struck by some of the toughest cases I’ve seen are patients who are taking a numerable meds often, 10 to 20 range and I think, some people talk about finding your area that makes you angry and I feel like this is something that I get worked up about. Where I feel like there are many cases that we come along where the amount of good that we’re doing with our meds may not actually exceed the amount of harm that might be caused in some cases. It can be very challenging but I think also, really meaningful to patients and intellectually stimulating to work through that with them and figure out where things can be cut back or rationally de-prescribed and we can talk more about that. Then I think, just from a policy standpoint, and I know a lot has happened in the Geriatrics world with the recent approval of Aducanumab. But I think a lot about the cost to society for medicines and to Medicare and what we could do to maybe reign that in. So it’s kind of those two experiences together that got me going.

Alex: Are you suggesting paying 56 billion dollars more than the NASA budget for just one drug that doesn’t work may not be the right thing with Aducanumab? [laughter]

Matthew: I’m hinting at that yeah. [laughter]

Eric: That’s another podcast. [laughter]

Alex: On our last podcast which had nothing to do with Aducanumab, Eric managed to work it in three times.

Eric: Let’s see how many times I get it in this time.

Alex: Keeping score over here.

Eric: All right Matt, I’m going to turn to your paper first, just published in the Journal of American Geriatric Society. So tell me, is this whole polypharmacy thing, specifically for people with dementia, is it common, is it something that we should actually be worrying about? Is it more common than people without dementia?

Matthew: Yeah, I think that our paper, going in to our paper I had a hunch that the answer to those question was going to be yes and in writing it up and getting it published I was blown away by how common it is. It’s in fact super common amongst people with dementia that they are affected by polypharmacy, which we narrowly define as taking five or more medications. Some people talk about this notion of hyper-polypharmacy and taking 10 or more medications, whatever definition you use. In our study it was highly prevalent, both in older adults generally, but especially people with dementia.

Eric: How prevalent?

Matthew: Off the top of my head I can’t remember exactly, I believe in the people with dementia it was around 70 percent, were affected by taking five or more meds. I think one thing that was important and unique in the approach was that this description applied to people with dementia living in the community, so a lot of the prior work, very valuable initial studies looking at people with dementia focused a lot on people living in nursing homes and then in populations that were attending less representative settings. Like Alzheimer disease centers and this is people who are going to their doctors offices and having regular outpatient visits with their docs and so it kind of is a real world sample of people with dementia.

Eric: And why do you think that is? Do you think it’s just because people with another co-morbidity are more likely to take more meds or is it something specific about dementia?

Matthew: Yeah, I think those are really good questions and we know a couple of things. We certainly saw this as well in our paper, but we know that people who have carrier diagnosis in dementia tend to have more co-morbidity, or to have multi-morbidity above and beyond the general population. So that is one thing we tried to do, in this analysis was to adjust for the number of co-morbidity, to adjust for age, to adjust for sex, these are well known phenomena that can affect the number of meds that people are on. The findings really held up beyond all those factors so it kind of answers the question of whether the number of meds was being driven by co-morbidities and it seems like there was something above and beyond that.

Matthew: And as to what that is, in your question I think some of this is really just conjecture but based on my experience and based on some of the other articles I’ve read over time I think you could pause it. Many possibilities, some being the discontinuity of care that people with dementia have as they go through the medical care system and then they have a number of different doctors who are looking at their medications. They may find that it is harder to communicate, either with the doctor or with their caregiver, depending on the stage of dementia about which meds are working and which ones are not. There may be other factors related to the care of dementia in terms of behavior management that leads to a cascade of prescribing, whether or not that’s indicated or has good data which I would argue it doesn’t. It is common practice to treat some of the behaviors that go along with dementia with certain medications.

Matthew: I think those are all possible candidates for why. It was very striking looking at the results on the paper. Just how polypharmacy was common but it was also polypharmacy that was driven by medications from a multitude of categories. It’s not just central nervous system medications or dementia medications, it’s medications for the heart and anti-coagulants. Anna works on vitamins, it was pretty telling that it went across categories.

Eric: And I’m seeing some, so I’m just going to look at your table too from jags. One side of the table is probably a visit with a least one prescribed medication use and if we just drill down since you mentioned anti-coagulants, coagulation modifiers, 18 percent in those with dementia, 13 percent in those without. Now is that 18 percent of people with dementia are on it or 18 percent of visits? How should I think about that?

Matthew: Yeah, it’s kind of a quirk of this data set, it’s that these are estimates about office visits. So the way to interpret that table and that statistic is to say that of a nationally represented sample of office visits in the United States, 18 percent of them will have someone that’s on at least one anti-coagulant for the people with dementia compared to the non-dementia group that you mentioned. So people walking in the door for their office visits, it’s like one in five.

Eric: Anti-coagulation, very common for individuals with dementia. It is interesting that Aducanumab the exclusion was anti-coagulation yet it’s still, FDA makes no notion, no mention of that in their labeling. That’s two Alex says, I’ve got one more Aducanumab.

Alex: You’ve got two, we have the Mike Steinman one so it’s been on a podcast three times. [laughter]

Eric: Oh come on! I’ve still got one more! [laughter]

Matthew: That was pretty good too, that was a nice, sly, glide into it.

Alex: Mike we should get your perspective too on this. What makes, you’re both on this paper and your co-pi of the USD prescribing research network, what makes prescribing so easy and de-prescribing so hard in general for patients with dementia in particular?

Mike: That’s a great question. I think there’s not one single answer and it’s probably the way our entire health system and our culture of medicine has been constructed. But I think probably some of the key factors are that we as doctors and clinicians, we want to do something to help patients and often times the way we persevere something as doing something and the patients perceive something is being done or to help them is to give them something. In this case, give them medication. In the act of taking something away, either denying it in the first place or god forbid stopping something already taking can be taken as a sign of lack of caring or lack of attention to them. It doesn’t of course mean that’s actually what’s being intended but they can be persevered that way and so the psychology of it really plays in I think both the clinician part and on the patient part. We just want to do these positive things for our patients and patients want positive things to be done to them. And often the simplest thing that we reach in our tool box is the medication.

Mike: There’s of course the unintended consequences of the guidelines, and clinical [inaudible 00:15:20], there’s a bunch of other factors as well. But I think that really plays into it. Why it’s especially prevalent for dementia, I think is not fully understood. One can hypothesize like Matthew said about a bunch of factors, patients having more difficulty disclosing difficulties with medications, side effects difficult with adherence which can further bury de-prescribing and de-escalation. And again in the instance of dementia, such a devastating disease. We all want to do something to help these patients because we know we can’t do that much for the dementia itself. And so I imagine those things might be playing a role, either way it’s unlikely to be one single factor but the positive spin on this paper is we have a lot of room for improvement which is a challenge but also says there are things that we as clinicians can do to help our patients. Probably by more judicious and how we think about giving medications for them.

Eric: And it is interesting that for a disease like dementia where caregiver burden is such a huge issue, that when we’re looking at people with dementia, these visits I think more than five medications or five or more medications. 72 percent with dementia that’s had five or more, 43 percent 10 or more. In a simple intervention to relieve caregiver burden may also just be decreasing some of the meds so you’re not fighting over the meds everyday, you don’t have to get it refilled as much. Why isn’t that a bigger issue and why aren’t we stopping some of these medications because of that? Matthew?

Matthew: Yeah, you’re getting close to the things to the things I guess that Anna may be get fiery but I think part of my interest in polypharmacy is really just the fact that in a case like this it seems so clear to me that non-pharmacologic support for caregivers and kind of thought poll approach to which medications are really helping, is the intervention more than kind of the totality of medicines that were giving. None of these meds are really, some of them may be guideline concordant for various chronic diseases but it’s clear that an aggregate in medications are not the solution to this big societal problem. You could make another reference to Aducanumab at this point but I think as to why, obviously I don’t think my study answers it.

Matthew: I do think it’s really important to think about what is the burden to taking a lot of medications and in particular what’s the burden in dementia when there maybe a diad or caregiver who’s suffering from burnout. There are some research scales and whatever to scale that amount of burden but I think clinically we see that when people come into the office, that they’re like “I have three medication administrations a day and some of them are inhalers, some of them are PRN and then I give half a dose of this”. It also to me represents a very radicalization of people’s life, they can kind of take over the cadence of the day to day in a way that if people have limited time or are thinking or focusing on quality, that may not be what someone wants kind of priority. I know that doesn’t quite answer your question but it’s kind of related thoughts.

Eric: Yeah. I also wonder, Anna, going to you and your paper. We talk about some of these medications may be guideline concordant, for example, anti-coagulants in people with atrial fibrillation, we want to prevent a stroke. A stroke may be devastating to somebody. Keeping these people or starting these people on anti-coagulation may prevent a stroke and decrease further disability and frailty. What are your thoughts on that and what have you learned from your studies?

Anna: Yeah, absolutely. I think that’s been the dominant perception and I think this whole paper started with us questioning that, questioning those guidelines because if you were to follow guidelines the vast majority of older adults will qualify for anti-coagulation and as Alex was mentioning that’s just now what happens in real life practice. It’s not clear, I don’t think whether that’s clinical, wrong or not, meaning is that too many or too few. So I think what we really tried to understand is, just as you were saying, stroke is really the most feared complication of atrial fibrillation, but most of the information that we have about how it affects people in the long term is very short time courses, like 30 days. And that’s in terms of mortality but also most importantly in terms of outcomes that we know older adults and their families care most about, like function.

Anna: What we tried to do was using a similar set of data, basically look and see over the long term what happens to those who have a stroke and who have atrial fibrillation and suffer a stroke, and how does that compare to a patient who has atrial fibrillation who does not have a stroke. Cause as we all are aware, atrial fibrillation is a co-morbidity that often happens in conjunction with a lot of other co-morbidities. It also tends to happen at the same time as other geriatric syndromes. The hallmark one is falls because that’s what we always are worried about and thinking about in these patients when were thinking about starting anti-coagulation. And so they have a lot of other risks and other reasons that they might lose function over time aside from a stroke.

Anna: We were really trying to get those two questions, so hopefully that answers your questions. That was the goal. We know it’s bad in the short-term but what happens in the long-term? And also how bad is it compared to just a patient who has atrial fibrillation who doesn’t have a stroke.

Eric: I can imagine. Just my clinical gestalt, you have a stroke, you’re going to have worse disability. Is that what you found?

Anna: We did find that, so big surprise! No not at all. So yes, we did find essentially that there’s a big drop in function right after stroke. So underscoring that stroke prevention is super important but the other interesting things that we found, there’s a couple things. So first is that just as I was saying patients who have atrial fibrillation alone without stroke, they’re function declines over time as well just because most likely it’s a marker of frailty and disability in and of itself. But also interestingly, after stroke there’s that big drop but it doesn’t look like stroke actually accelerates disability. People continue to climb at the same rate as if they never had a stroke. So that’s kind of interesting but the second part of the analysis is that really what I hope we drove home in the paper is that when you take all patients with atrial fibrillation, those who experience stroke which is about 1 out of 13. It’s very devastating, no question about that. But the vast majority of disability in that whole group comes from other things.

Anna: Stroke in and of itself only accounts for less than 10 percent of disability and that includes things like ADL function and IADL function and move to a nursing home. So for all three of those outcomes, stroke is a very minor contributor. And so I think that is what we’re trying to get home but it’s very important for the people who experience stroke but that can’t be the end-all be-all when were managing these patients. There’s a whole host of other things that lead to disability in patients with atrial fibrillation.

Alex: And Mike, I’m interested in your thoughts about this as somebody who’s a geriatrician and has cared for patients I’m sure who’ve had atrial fibrillation and weighed this decision about whether to anti-coagulate or not. Thoughts from you on the implications of this study, for your practice?

Mike: I mean I think it was really great, important work that Anna did and probably the most important thing of all is to sort of helps to keep our eyes on the prize. I think there’s this idea that we often have when we think about medication treatment that’s like we give the preventative medication whether it be anti-coagulation or Statin or something and if we don’t give it the persons going to have the event. And if we do give it, they’re not going to have the event and aren’t we so great. But of course we know the number needed to treat is high for many of these drugs. Meaning that many people who we’d give the drug to will have it anyways and many people who we don’t give the drug to will never have the event and would’ve never had it. Whether or not we would give them the drug.

Mike: So our difference in these things is often marginal. Maybe five percent number of people we reduce an event, maybe 10 percent if we’re lucky? Something like this really helps keep us focused on the fact that a lot of these medication treatment choices are not going to make a big difference for our patients and it doesn’t mean that we should ignore them and we should not ever treat anyone with anti-coagulation. Far from it, but it means that we need to put it in perspective, both in terms of being realistic about what these drugs can achieve and balancing that against their harms. Like leading events or patient, or like Anna was saying, disrupting their quality of life because they’re afraid of going out, because of the risk of bleeding. And also it keeps our eyes on the prize about doing other things, but what else can we do to prevent functional decline. Even if the person doesn’t have a stroke and are there other things we can do. We know we’re not God and we can’t fix everything but I think it frames it in the big picture is the most important take away that I got from this paper.

Eric: I feel like for some of the medications were seeing polypharmacy from Matthew’s paper, like anti-psychotics. It’s fairly clear that we should be trying to reduce those. I think some of the cardiovascular stuff like blood pressure medicines there’s still maybe benefit like anti-coagulation I find anti-coagulation really hard in my own clinical practice. Like for example, we had a recent patient with severe dementia, not end-stage but had other co-morbidities, admitting him to hospice and the medicine team said “Oh my god why is this person even on anti-coagulation, we should absolutely stop it”. I said “You know sometimes we actually have hospice patients that we continue anti-coagulation”. This person was on it for a-fib, had a high chadsvasc score. It’s one of those things that we think about but as I thought about it for this particular patient, I wasn’t worried about that massive stroke that was going to cause death because that was something that he was not worried about. I think what was worrying people was what if he had a small stroke that caused some disability or a series of smaller strokes with his chadsvasc I think gave him a 10 to 12 percent chance of having a stroke within the year.

Eric: So Anna, as a hematologist, what should I do for that patient? And also given your paper that his function is going to decrease no matter what I do, but maybe there will be a bigger drop right after he has a stroke. Should I use the palliative care mantra, depends on their goals which is also not incredibly helpful cause it also depends on the evidence. Is it going to benefit someone, is it going to hurt someone?

Anna: Yeah, that’s the power ball question and like Matthew was saying I think this is one of the things that really gets me riled up cause it’s a super common question even for hematology consultants.

Eric: Yeah, and the paper that you did the Jama editorial on, the Jama IM showed that a third of nursing home residents with advanced dementia were on anti-coagulation.

Anna: During the last six months of life, yes.

Eric: Given the last six months so they were in the last six months of life, they’re on anti-coagulants just like my patient and I actually think because it was two weeks ago, I continue the anti-coagulation. Did I do bad? Is that the wrong answer? Am I one of those bad one third of providers?

Anna: No, I think the other interesting thing about that paper and maybe this is sort of where you were coming from is that, the sickest patients who’d been in the nursing home longest and had the most severe markers of dementia were the most likely to remain on anti-coagulants.

Eric: Yeah.

Anna: Which is exactly the opposite of what you might anticipate but I think that paper really just should service the people we were editorializing on, it really should service a cause to action, that there’s really no rational framework. At all. So I think the issue comes down to, it’s sort of similar to Louise Walters seminal work on how do you decide which patients benefit from cancer screening, and I really think I was influenced by her work in that area. In that we use, just as you’re saying, we need to integrate evidence, for us were trying to prevent from quantitatively, how much is this preventing thrombosis and stroke versus quantitatively how many bleeds are we going to cause. Sure, those should be the pillars and that’s what the chadsvasc score and all the bleeding risks scores are trying to get at. But there’s all the stuff in the middle that we need to integrate in a rational way and that I think has not been done, and that’s where I do think that the art of medicine and the role of geriatricians and palliative care doctors and hopefully hematologists, cardiologists, with that same esos. Trained impeccably by Dr. Smith and Steinman, and you obviously Dr. Widera, can come into play.

Anna: And that we should think about how long do we estimate this person has to live, such that they might get the benefit. So that’s jumping off of Alex’s work on prognosis. Because there’s so many things that could affect them before a minor stroke does. We should also think about, just as you did, thinking about if my patient doesn’t care about the major stroke but really still wants to be able to walk around the grounds with a walker and a minor stroke might prevent that, that should go into that calculation.

Eric: Yeah.

Anna: Or will they be completely scared to do any kind of activity because they get a cut or a bruise from gardening and it just never stops bleeding. Those are the things that we don’t always ask about and definitely researchers do not measure in clinical trials for example and that I think is where we just need to blow this thing up.

Eric: I think in that paper you editorialized on, people all had very advanced dementia.

Anna: Yes.

Eric: Very poor functional status. Some of the patients like the patient I admitted still was able, not advanced, severe, still was able to walk around, still had some potential benefit as far as reduction and disability.

Anna: Yeah.

Eric: I think the challenge that I’m also thinking about, I’d love your thoughts about this too, Mike or even Alex. For colonoscopy, it’s clear there’s lag-time of benefit. It takes 10 years to see a benefit because you’re trying to find something that’s either incredibly small or pre-cancerous. Is there a lag-time benefit for anti-coagulation or is it, you start some anti-coagulation you see the potential benefits and harms around the same time? Or do we even know the answer.

Alex: I think the answer is, I remember talking to Sachin about this. Who’s senior author on Anna’s paper, that the benefits accrue almost immediately as you say and the curves diverge almost immediately. So that there is, this is a different paradigm from our usual lag-time to benefit paradigm. That said, we’re talking about risk, the study talks about risk over a period of time and it’s usually a year rather than the short period of time that the patient has left to live. So what do you do with that risk? Do you divide it up into the increment of time that the patient has to live? I completely agree with Anna, we need a new way of thinking about this that incorporates plans, goals, patients preferences for function their fears, concerns. It does come back to the geriatric palliative care mantra of goal focused decision making. And this has come up not just in atrial fibrillation but also as I’ve talked about with Anna for venous thromboembolism.

Alex: Patients who have a DVT or have had a history of PE. They often come to hospice or we’re taking care of them in the setting of palliative care and we just don’t know what to do often with these patients. Should we continue the meds, what benefit are they getting, is it symptomatic, what would happen if they had a massive PE as a result of the DVT, is that something that they would likely end their life quickly and hopefully painlessly. Again, the similar scenario we have to come back to goal focus care Anna any thoughts from you on that?

Anna: Yeah, I think I totally agree. This is my pet issue, I think we undervalue the patient experience of weening. We’re all really scared of the clots but my clinical experience has told me that patients suffer a lot from bleeding and we may not know it because it doesn’t always come to medical attention. I think that’s another area that needs to be further explored as were making these decisions.

Matthew: If I could just interject on this topic, two things that you guys are saying that I feel really riled up about right now. One is that the way that teach and learn about medication prescribing is a complete void with respect to this kind of life long decision making. The medicine is started by maybe a hospital team or a very well meaning physician at one point in time and I don’t think there’s a stewardship of really analyzing every medicine at the level of graceful detail that you guys are going into here. And then as well with the studies, with the way that we decide whether or not to approve medications, how we think about the benefits as they accrue, especially to older people with frailty or old people with cognitive impairment. There’s so much richness to what you’re talking about that I feel like is not yet translated into what we use to say whether or not we want to pay for medicine. So I agree.

Alex: So here’s a question, what can we do about this? What can we do about these issues? If you could wave a magic wand, we’ll take each of you in turn and do one thing differently. What would it be, would it be education, would it be the way that we approve drugs, would it be something about incentives for clinicians? Mike, why don’t we start with you first.

Mike: You give me that easy and hard question at the same time. I wish I had a clear answer but I think to build on what Anna and Matthew were saying which is about just taking the time to talk to the patient. Not only in the gross abstract but like you’ve been taking Coumadin for a long time or DOAC, what’s it like for you, are you worried about these things, do you bleed, how often, does that bother you or not? Does it restrict your activities? You get a really different answer depending on who you talk to but those conversations take time and for busy physician/nurse practitioner at a clinic, that time is really valuable so I think a lot of the positive directions we can have in this sort of taking it at of the physician or nurse practitioner’s hands to have those conversations. Engaging pharmacists more in clinic, and finding other creative ways to have these conversations to really build an understanding of what the patient is actually experiencing taking that medication and how their goals and values play out into that specific decision.

Alex: Yeah I think that’s critical, it doesn’t get at the underline issue that you talked about before, Mike. Which is, clinicians feel like they need to do something and the prescribing is the doing something and the de-prescribing is going in the opposite direction. That’s got to be a part of it somehow too.

Mike: Yeah absolutely. I’m saying education in a broad term cause it’s really more than just education, it’s about motivation and getting people to start buying and really embrace what you’re talking about, as opposed to just lecturing to them and understanding where clinician values are and what their concerns are. But this applies as much to clinicians as it does to patients and their caregivers. It really involves, it’s going to be a long term process of changing the culture of how, in the practice of how we deliver care.

Alex: Yeah, we know academic detailing works, could we do academic de-prescribing and detailing, something like that.

Mike: I don’t think so, I do and I don’t think so. If you have highly protocolized decisions like it’s clear this is a bad medication for this patient, for almost all patients with this situation, then yeah academic detailing is something that can work. But how you apply academic detailing to embracing these complex conversations and creating the structure to allow this to happen, for people to act appropriately and get over the deeply entrenched cultural and psychological barriers that we as clinicians have, and patients under caregivers have. Academic detailing could probably start to get us that place but I suspect that the current model of academic detailing is going to be insufficient to really get us towards that goal, it’s going to involve a much deeper level of change.

Alex: Mm-hmm (affirmative) Anna how about you? You have a magic wand.

Anna: Yeah, I mean I wish I had the wealth of experience to draw on. I’ll just pick one thing, I come from hematology, oncology where clinical trials are all we care about but I guess I would say, I think that there’s a moral responsibility to make clinical trial populations reflect the patients who actually end up getting prescribed medications. I think that’s done in certain areas but not so much in the realms that I work in. Secondarily, making it a population more reflective of the patients who get the drug and then making sure that the outcomes that we measure are the things that matter to patients and their families. As opposed to just medicalizing everything. That’s my dream

Eric: So Anna, hypothetically if I were to develop let’s say an Alzheimer’s drug that may barely work, I should probably also if I’m going to do it indication as the FDA, I should probably, the indication should look like the people enrolled in the trial?

Anna: Yeah you might consider that. [laughter]

Eric: Mild dementia maybe just keep it to those individuals.

Anna: Yes, agreed. Yes, this has wide ranging implications just as you say.

Mike: Two trials not just one and then pick the one that works the best.

Eric: That’s evidence based medicine. I remember that’s what they taught me in med school around evidence based medicine. Pick the trial that proves your point.

Matthew: Actually shut the trial early and bring it back many months later, with new evidence that you bring to light. Sorry, we’ve gone off the rail.

Eric: Any other magic wands Matthew?

Matthew: I’ll keep it brief and build on something Mike mentioned. If I had the magic wand I would wave it and it would have a profound cultural ripple effect. Cause I do think research is important but I really think that root of a lot of what we’re talking about is culture and biomedical culture and it would bring patients, physicians, insurers, FDA advocates, everyone into line around exactly what Anna was talking about. Making sure that the things we do in medicine, so today we’re talking about medications but the medications that we give to people on balance are doing more good than harm. They’re helping them reach their each individual goal. It sounds easy and obviously it’s extremely hard and everyone who’s listening to the podcast knows that it’s often extremely gray but I think we can do better.

Eric: Well I want to thank you all before we leave. Alex do you want to end with a little bit more song?

Alex: Little bit more, could drink a case of you. (singing) “Oh I am a lonely painter, I live in a box of paint, I’m threatened by the Devil and I’m drawn to those that ain’t afraid. I remember the time you told me, you said, “Love is touching souls”. Surely you touched mine cause a part of you pours out of me, In these lines from time to time. Oh, you’re in my blood like holy wine you taste so bitter and so sweet. Oh, I could drink a case of you, darling and still I’d be on my feet, I’d still be on my feet.”

Eric: Matthew and Michael big thank you for joining us for this GeriPal podcast.

Group: Thank you

Anna: Beautiful Alex.

Eric: Always a big thank you Archstone Foundation for your continued support of the GeriPal podcast and to all of our listeners. Thank you for continuing to support the podcast. Goodnight everybody.

Alex: Goodnight!