Truth telling is an ethical pillar of medicine. But, are there instances when it is ever ok to lie to a patient? In this episode of the GeriPal podcast we explore the use of deception and lies in modern healthcare, from those sweet little “therapeutic lies” commonly used in dementia care to withholding a diagnosis like terminal cancer.

While we don’t pretend to know all the answers, we do have some wonderful resources that have helped shape our thoughts on the use of lies and deception in medicine:

- Tony McElveen. Lying to people with dementia: treacherous act or beneficial therapy?

- Schermer M. Nothing but the truth? On truth and deception in dementia care. Bioethics. 2007.

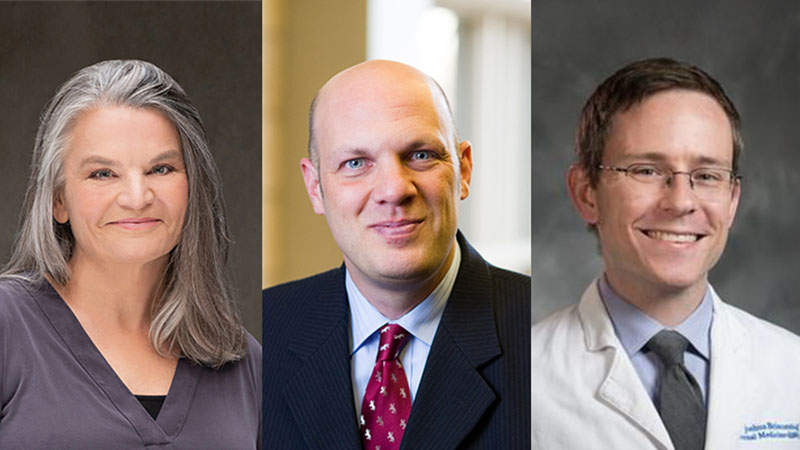

by: Eric Widera (@ewidera)

Eric: Welcome to the GeriPal podcast, this is Eric Widera.

Alex: This is Alex Smith.

Eric: Before we start, Alex, do you want to give us a little song?

Alex: Yes, this is an appropriate song given the topic of today. “Tell Me Lies” or “Little Lies” I think it’s called.

Alex plays “Little Lies” by Fleetwood Mac.

“Tell me lies, tell me sweet little lies, tell me lies. Oh no, no, you can’t disguise, you can’t disguise. Tell me lies, tell me sweet little lies.”

Alex: The topic today is “Sweet Little Lies.” Eric, is it ever appropriate to lie to a patient?

Eric: I remember being taught in med school that no, the fundamental principle is medicine is trust and the trust that we build with our patients and their family members. Lying is bad.

Alex: Lying is bad. Is it really so black and white? Maybe we need somebody else to help us think through us. I’d like to introduce Kathryn Eubank, who is here at UCSF and is the Ethics Steward. She has some experience that she’s going to share with us, not just clinical experience but also we’re going to rely on her ethics background as we talk about this issue of whether it’s ever appropriate to lie to our patients. Welcome, Kathryn.

Kathryn: Thank you. Thanks for having me.

Eric: Is it ever okay to lie to our patients?

Kathryn: No, I think Eric is right. We’re taught from very early on in medical school that the basis of our relationship with our patients is trust and absolute truth-telling. I think we may have all used… is it lying?… definitely falsehoods, or little white lies at times with our patients.

Eric: Sweet little lies.

Kathryn: Maybe sweet little lies. We have had some cases where we do this specifically with patients who may not understand that they’re being lied to. I think it’s probably most often used in pediatrics and dementia care with older adults.

Alex: Let’s start with one end of the spectrum because I think there is a spectrum here about lying in those. Some of these are sweet lies, or I think what we sometimes call therapeutic fibbing, therapeutic fibs. Then the other end are things that are really nefarious, intended-to-harm lies. There’s a spectrum in between. Maybe we could start with talking about some things on one end of the spectrum that are the sweet little lies, variety.

Eric: What would be an example of a therapeutic lie?

Alex: What about those black mats that we have that we’ve seen in nursing homes? They’re actually tiles that are black, outside of the elevator.

Eric: I’ve seen those.

Alex: What’s the idea there?

Eric: I think they are to prevent people with dementia from crossing it because they fear it’s a cliff. People often put them in front of elevators or doors going to stairs, because it’s supposed to create some type of fear that they’re approaching a cliff, so they back off and wander somewhere else.

Alex: What do you think about those, Kathryn? Ethically are those acceptable?

Kathryn: Yeah, that would definitely fall in the realm of what we would call deception. I think what we’re intending there is that we believe that we’re acting in the patient’s best interest by preventing other things that we may not fee are as beneficial for the patient. If we don’t block them from going on the elevator, then what happens?

Eric: They wander outside and they may get hit by a bus or …

Kathryn: Yeah. Then we might have other ways to block them from going on the elevator. Most we would not choose to have, either restraining a patient, tying them down, or giving them medications to do that. I guess we would say, if you’re going to weigh out risk and benefit, maybe that’s the lower risk, the lesser of the 2 evils.

Alex: What we choose for our patients, sometimes we’re choosing the deceptive method as the least restrictive method or the least potentially harmful method for the patient.

Eric: Is that a lie or is that something less than a lie?

Kathryn: Well, it’s absolutely deception. There’s no question that we plan to deceive when we lay out those black tiles for the patient.

Eric: Well, what’s the difference between a lie and deception then?

Kathryn: I think some people would say a lie is something that’s verbal, spoken or written in some way, whereas deception is much broader than that. A lie can be deception, but deception would encompass more than that. Deception is even me withholding something from you, the thing that I don’t tell you.

Alex: Other examples of this. What about just common, every day that seem to be more accepted. When we mix medicines and apple sauce and give them to patients with dementia, that is deceiving them because we’re not telling them that there’s medicines in here. The idea is to get their medicines into them mixed in a substance that they want to eat, is it?

Kathryn: Seems benign, but here’s what I think is interesting. If that was a younger person with a mental disorder, we could not do that without either some type of informed consent from a guardian if they were present, or we have to go to court before we can force medications on them.

Somehow we’re very paternalistic to these older adults who we think have this almost childlike demeanor and that we’re going to hide their meds in their apple sauce, and we don’t ask necessarily permission to do that. We’re making that unilateral decision to do it.

Eric: I’m going to turn it up just a notch, then. We had a patient who, he was in his 60s, with a metastatic cancer to the brain, he’s got a big lesion right next to the hippocampus, couldn’t remember anything past 5 minutes, so you’d have a discussion with him about his cancer, and 5 minutes later he would completely forget.

He was undergoing radiation therapy. Every morning the intern had to go talk to him about why he had to go and wake up from his sleep, get ready to go to the radiation treatment center to get this lesion treated. Every time it was an emotional catastrophe for him. It was the first time that he found out that he had cancer, and at some point people were questioning, “What are we doing to him? Should we not tell him he has cancer?”

I guess that’s again, more deception than lie at that point, or potentially coming up with a therapeutic fib of where he’s actually going.

Kathryn: I think that some of the same principles would apply that we use with other patients. Is there somebody that you could check with before you deceived him?

Eric: He had no family, but good point, could have asked a family member.

Alex: Interesting. There might be something about going to family members to obtain permission to lie to loved ones with dementia, or in this case cancer affecting the brain. Well, I guess the other thing that I was taught, we lamented how even 10 years before our training doctors would routinely not tell people about their cancer diagnosis.

Oftentimes it was a family member who said that they shouldn’t be told because it would be too hard for them to hear. In that case you’d have somebody who we have reviewed it with a family member, the family member said, “Don’t tell them.” Should we not tell them? What’s different?

Kathryn: Time is different. I mean, honestly, that was an accepted thought at some point. I do wonder about that with these dementia patients, if we’ll look back at this 20 years later and say, “What were we doing, thinking that it was okay to lie to these patients.”

Alex: The norms have changed over time and what was acceptable then is no longer acceptable. Some of these sweet little lies that we partake in now may no longer be acceptable normatively in 20 years. What about these, sometimes the lie or the deception brings the surroundings into that patient’s world view.

What I mean by this is, for example, in Europe there are some nursing home residences, long-term care facilities, where they recreate an environment that existed 20, 30, 40, 50 years ago because those are the memories that people with dementia retain. That’s entering into their world view in a way. They might have things like a bus stop, an old-time bus stop that they go stand at.

There’s no bus that’s ever going to come. We’re deceiving them, but they feel like they’re acting out their daily lives as they are experiencing them in the world as they see it, which is the world of 50 years ago.

Eric: Yeah, or some of the dementia villages where they have full grocery stores, bus stops, big open gardens, but it’s all enclosed so you can’t leave. It’s somewhat real, but it’s somewhat like the Truman show, where everybody is in on it that this is all fake.

Kathryn: Is it fake? We have cases where we’re definitely doing fake things with patients with dementia. We have a patient that needs to go pay his rent, so we set up a false landlord for him where he can take his play money up to the fake landlord in the hospital and pay his rent. That is a very fake situation. There’s nothing real about that, but the dementia villages are not fake.

If you’re going to the grocery store, they’re picking up their coffee and their bread, or if they’re going to the hairdresser, they really get their hair dressed. It’s not a fake hair-dressing. Is it truly artificial or not? Is that the same level of lying as me completely playing make-believe like I would with my 4-year-old nephew or niece?

Alex: This gets at an underlying issue about treating older adults as younger children, which has already come up a couple times today. The other article that’s been in the news recently is about doll therapy, for patients with dementia, where they give them a doll. The people with dementia hold it and cuddle it.

It’s not clear if they’re treating it as a doll or whether they’re treating it as a baby and they can’t quite tell that it’s a doll because they’re life-like dolls. In any case the issue is, are we treating them as children who play with dolls and not as older adults deserving of respect and esteem?

Kathryn: How does that compare? We know that for pet therapy, and we have plenty of research on pet therapy that that definitely can calm patients, that they find it comforting. They can form a relationship with that cat or puppy that wanders in the nursing home. There are even those studies that show that those animals are sensitive to that patient’s needs. On days they’re having a rough day they may spend more time on that person’s bed.

Are we using the baby doll because it’s cheaper and easier for us than the pet, which is somewhat less respectful to that patient than the ability to form a real relationship with an animal.

Eric: We don’t have answers to these questions yet, but maybe … We’ve talked about some of the considerations. One of the considerations is, would family approve or this, or a patient’s loved ones, surrogate decision makers? Another consideration is what are the alternatives? One of the things that might be helpful as we think about this is to push the envelope even more, ratchet up another notch.

We had a situation at one of our hospitals where a patient with dementia was given a letter by some well-meaning providers, and this letter was addressed from an organization that this patient had worked for previously. The letter was encouraging that patient to make the transition from the hospital to the long-term care facility. It didn’t work out so well, did it?

Kathryn: No, unfortunately, the patient realized that they had not worked for that organization for some time. Even though it was very well-intentioned, which was to make this transition easier so that the patient could adjust to it much easier than, for instance, their transition into the hospital, it actually ended up creating a lot of confusion both for the patient, because they were confused of why this organization would send them a letter 20 years after they knew they didn’t work for them anymore.

Then also for the staff who weren’t sure what to do. Once the patient realized the deception, do you double down on the deception and try to convince them that it’s real, or do you back off? Then what have you done with that trust with the patient if you say, “We’re sorry, it’s not real.”

Eric: I guess that’s the problem with deception and lies is you run the risk of destroying any trust that’s built up between healthcare providers and patients if the deception fails.

Alex: Right. If you’re caught in the lie it doesn’t look so good for the healthcare provider and can erode that trust. The other important piece that you bring out here is that the deception may have a pernicious quality in that it erodes the values of the healthcare providers who are trying to do their best in a difficult situation, so that over time they might feel uncomfortable lying and participating in this deception, or it may make it easier for them to deceive other patients.

Kathryn: Well, you’re teaching them to stop listening to that inner voice that says, “We shouldn’t go there.” It gets duller and duller and duller over time if you ignore that thing that says, “this is not the right thing to do.”

Eric: Right, it may erode their integrity and their honesty, and that may compromise their ability to be the best physicians or whatever kind of healthcare providers they are.

Kathryn: If I deceive [a patient] in this situation because I think I’m really, honestly I’m doing this in the best interest of the patient, then why can’t I not tell the guy he has cancer if I think it’s going to be stressful to him? I can make him have a good life till the end, without ever telling him he had cancer.

Eric: Then the question is, because I feel like after listening to this conversation that there are these small little lies, therapeutic fibs, individual with severe dementia who thinks his wife is still around but she died 10 years ago. Where not every day you want to remind them that the love of their life is dead, where there may be a role in participating in this therapeutic fib versus going down all the way to the other side where it feels very uncomfortable where there are some lies that go too far.

Not telling the patient that they have metastatic cancer or are dying because one of their family members wants to protect them. Where do we draw this line?

Alex: I don’t know that there’s a line that you can draw. It seems that it might be more helpful to think of, what are the considerations at stake? I think we were coming up with a list here. We added to that list, what is the effect on other healthcare providers? How many people are needed to maintain this fiction and what’s the corrosive effect there? Which would argue against lying unless it’s one of the only choices available in order to protect the patient’s best interest.

Kathryn: I think another point that was brought up, too, is that we have to have a way to better assess what their true capacity and dementia level is before we lie. You might think that they’re going to fall and go along with that, but in these cases where they’re not quite that far along then you have really created a lot of anxiety and mistrust with them.

Eric: I’m sure this situation comes up even in everyday nursing care across nursing homes throughout the US. “What are you putting in my applesauce? There’s something in here?” They’re picking up on that and that builds mistrust between the patients and the nurses.

Kathryn: Would this be something you could think about beforehand and say, “I’ve been diagnosed with dementia. I still have my faculties about me and can make decisions.” Would you sign an advance directive that says, “If it comes down to restraining me or deceiving me, I’m okay with just deceive me. Don’t give me those drugs.”

Alex: That’s a creative idea, an advance directive for deception. I like it.

Eric: It sounds like, to summarize what I’m hearing, it’s important first that we figure out, “Does this person have the ability to make their own decisions?” Whether or not they actually want to hear the news or not, assessing their level of capacity, their ability to make autonomous decisions. For instance, the patient with cancer, asking them how much information that they want to know.

Individuals with advanced dementia, severe dementia, also assessing what would it take also to create that deception and the harms and the risks of doing so.

Kathryn: I think, in general, in the system what we want are checks and balances. We know historically that when clinicians are doing things with the very best of intentions, if they’re the only one that’s so focused on that, they can get this tunnel vision and they’re not seeing the full picture and they go down the wrong pathway.

Part of that checks and balances has been that we very highly honor patient autonomy or a court has to step in and give permission for that, or a surrogate has to step in and give permission for that, or an ethics committee steps in and gives permission for that. There are checks and balances to make sure that your desire to do well by me does not go askew.

Eric: With that probably comes transparency, that it should be clear to everyone involved what’s going on and then if people are upset about it or feel uncomfortable about it, that there’s some way that they could appeal?

Kathryn: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Alex: Another scenario that I read about in this book, “The Moral Challenge of Alzheimer’s Disease” by Stephen G. Post, is this story called “The Last Tango in Paris.” The story is of 2 residents of a dementia care unit, a man with earlier stage dementia and a woman with more advanced stage dementia. This woman is a widower and she believes that this man, other resident, is her husband. She keeps buying him gifts and treating him as if he is her husband.

The man is enthralled by this and asks permission of the higher-ups at the nursing home if he can quote/unquote “cohabitate” with her. This would be, as he says, his last tango in Paris. The nursing home administration goes to the woman’s daughter and asks her for permission for her mother to cohabitate with this other resident.

She refuses, flat-out refuses, and says, “No. This does not respect my mother and who she is as a person. She was very faithful to her husband her whole life. Sleeping with this other man who she thinks is her husband but who is not, dishonors who she is and doesn’t respect who she is as a person.” Heartbroken, this resident of the dementia care unit was eventually hospitalized, developed pneumonia and died, his relatives say, of a broken heart.

What do you think about this scenario? What are the considerations at stake here? Should the nursing home administration have argued more forcefully for allowing them to cohabitate or not?

Eric: Be part of the deception.

Alex: Be part of the deception, right.

Kathryn: Right. I think you have to separate this out from the other issue that’s taking place in the nursing homes right now about whether older adults are allowed to have a sex life. I think this is separate from that because of the deception. Does she call the man by her husband’s name?

Alex: They didn’t mention it in the story. How would that change your perspective?

Kathryn: Honestly I’m not sure how much it would, but it would clearly mean that she really, truly … That’s different to saying, “I have a new relationship and now I think he’s my husband because that’s the kind of relationship I have with men. I don’t sleep around with men. I think he’s my husband. I’ve just remarried again.” I do think that’s different than saying, “This is Henry, my long-lost husband.”

Alex: My understanding is she thought this person was her husband.

Eric: The “ick” factor for me would be if he was pretending to be her husband, which would seem …

Kathryn: It’s taking sexual advantage … You could take this same scenario and move it out of there into any other adult situation…

Eric: A dark corner in a bar, where you think …

Kathryn: We would not think this was okay.

Alex: Right, an inebriated person or somebody who’s been given some one of these date rape drugs, for example, to make them forget, a temporary dementia, so to speak. It would seem abhorrent.

Kathryn: It would be abhorrent.

Alex: It would be abhorrent, but in this case you’re talking about maximizing happiness. Another consideration that people have raised is this idea of maximizing happiness for people who are in this state permanently. It’s not a temporary state.

Kathryn: Would she be just as satisfied buying him gifts, having dinner with him, spending the evening with him, or did she truly want the sexual relationship? I think that matters, too.

Alex: Right.

Eric: I think that goes back to the Truman Show is, the premise of the Truman Show is that you created this false environment for this individual where his life was perfect. He was happy. There were no lots of ups and downs, though, in his life. I think that there is something to uncertainty, not knowing where things go, and downs, too. If we just try to create the perfect, happy environment for people with dementia with no periods of sorrow or sadness, I doubt anybody in this room or listening to this radio show would want to live a life like that.

Alex: I wonder if we could go around and briefly summarize just 1 take-home message that our listeners could take away from this discussion. I’ll start. I think this idea of the pernicious quality, the corrosive effect on the virtues of, not the patient but the care providers, and all those who have to engage in the deception, is something that needs to be taken into consideration here.

Is this eroding their honesty and integrity in ways they might not appreciate because its happening so subtly. That bleeds over into the way that they approach other patients.

Kathryn: I think one of the take-homes for me as I’ve thought about it is that there are reasons that we have these checks and balances in the system. As well-intentioned as we may be at times, I think that those balances need to remain there in some form or another. If we’re going to use deception I think we should try to follow the same guidelines that we’ve set up for other things.

There needs to be some type of informed consent that’s involved if we’re going to do it, whether that’s from a patient themselves, if possible, or from a surrogate or a court system. Part of it is because I feel like the dementia patients are being treated differently than other patients. Somehow we think it’s okay in this population while it would never be in a younger adult, like with mental disease.

Eric: For me I guess the main take-home is I’m just going to pause more before I think about therapeutic deception. Is it the right thing? Or do you use something else? Instead of using deception, maybe just inquiring more about how they see the world and just validating their experiences. Alex, that was a great question. Maybe you can just end this off with a song as well.

Alex: This song starts out with one of my favorite lines from The Eagles, “City girls just seem to find out early.”

Alex plays “Lyin’ Eyes” by The Eagles.

“City girls just seem to find out early, how to open doors with just a smile. Rich old man and she won’t have to worry, she’ll dress up all in lace and go in style. You can’t …”

Sorry, I’m advancing this.

“You can’t hide your lying eyes, and your smile is a thin disguise. I thought by now you’d realize, there ain’t no way to hide those lying eyes.”