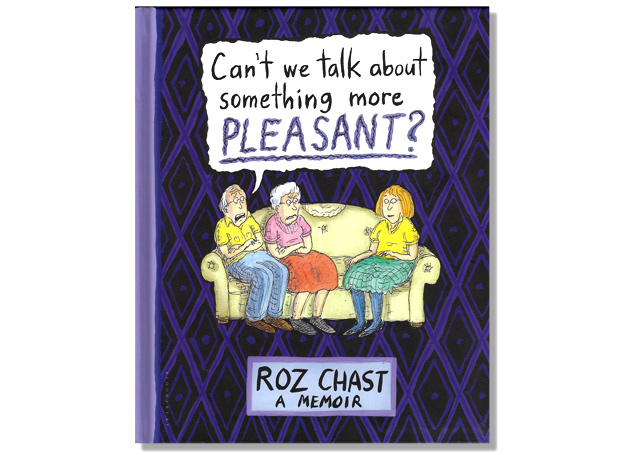

Roz Chast, a beloved and well known cartoonist for the New Yorker, has written a brilliant book that should be required reading for the geriatric curriculum. It is entitled “Can’t we talk about something more PLEASANT,” and the title comes from her parents’ refusal to discuss their advancing years and the prospect of death. As I read it I literally saw my entire field flashing before my eyes.

Known for her nervous looking pen and hilarious observations of urban life, she presents a starkly realistic portrayal of the last years in her parents’ lives and their progressive physical and mental deterioration. An only child, she takes on the responsibility of caring for them in their 90’s as they face a trajectory of decline that is the bread-and-butter of any geriatrician. Through the artist’s words and images, elder care is depicted in a way that is heartbreaking, funny, and quite accurate.

We observe Ms. Chast’s ailing parents through simple pen and ink and watercolor as they trundle through their last years, often in denial. The artist grapples with her feelings of guilt and anger as she takes charge of her parents’ finances and living situation, while deftly documenting the quirks of their personalities and the tenderness of their relationships. She fearlessly steps into their world of frailty and describes falls, social isolation, and cognitive changes, all while juggling her own family responsibilities. Her cartoon panels are peppered with personal photographs and the occasional flashback when we learn of her life as an overprotected, nerdy child with an overbearing mother.

Difficult and important challenges of geriatric caregiving are illustrated, including discussion of advance directives and driving after cataract surgery. Ms. Chast describes her shock at discovering the extent of her father’s cognitive deterioration, and does an outstanding job of presenting the anxiety and behavior changes that commonly occur in people with progressive dementia, as well as the stress and fatigue she experienced as a caregiver. When I read about her father getting lost in his apartment building and leaving the stove on, I was vividly reminded of events I have seen so many times with my patients.

The book realistically presents her interface with the healthcare system, including long waits in the emergency room, visits to the neurologist, and the transitions from assisted living to hospital to nursing home to hospice. On the way, she brushes nearly the entire gamut of geriatric syndromes including falls and fall related injuries, deconditioning due to hospitalization, depression, fecal incontinence, dysphagia, pressure ulcers, pain management, and progressive dependence in ADLs that often accompanies frailty. On the way she describes doctors who have no clue how to deal with frail elderly, and the difficulty of making choices regarding operative interventions in people of advanced age. Throughout her journey, Ms. Chast remains remarkably rational in evaluating her options and abiding by the choices of her parents.

At the very end when her dying mother enters hospice and becomes nonverbal, she presents a series of drawings that eliminate captions in a way that echoes her mother’s wordlessness. This series in particular brought back images from my years working as a nursing home physician.

The most important aspect of this book is the unflinching yet touching way her parents’ trajectory of decline is presented through simple drawings, and the very realistic observations and stream of consciousness that appear in the captions. This book can serve as a starting point for any student or family member interested in principles of geriatrics and the experience of growing old in America. Roz Chast is not a doctor, but with an accurate pen and sharp wit she combines art and medicine to create not just a memoir but a realistic portrayal of progressive frailty and death in a society and culture that usually ignores these issues.