Think about the last time you attended a talk on communication skills or goals of care discussions. Was there any mention about the impact that hearing loss has in communication or what we should do about it in clinical practice? I’m guessing not. Now square that with the fact that age-related hearing loss affects about 2/3rd of adults over age 70 years and that self-reported hearing loss increases during the last years of life.

Screening for addressing hearing loss should be an integral part of what we do in geriatrics and palliative care, but it often is either a passing thought or completely ignored. On today’s podcast, we talk to Nick Reed and Meg Wallhagen about hearing loss in geriatrics and palliative care. Nick is an audiologist, researcher, and Assistant Professor in the Department of Epidemiology at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Meg is a researcher and professor of Gerontological Nursing and a Geriatric Nurse Practitioner in the School of Nursing at UCSF.

We talk with Nick and Meg about:

- Why hearing loss is important not just in geriatrics but also for those caring for seriously ill individuals

- How to screen for hearing loss

- Communication techniques we can use when talking to individuals with hearing loss

- The use of assistive listening devices like pocket talkers and hearing aids

- Their thoughts on the approval and use of over the counter hearing aids

If you want to take a deeper dive into this subject and read some of the articles we discussed in the podcast, check out the following:

- Hearing Loss: Effect on Hospice and Palliative Care Through the Eyes of Practitioners

- COVID-19, masks, and hearing difficulty: Perspectives of healthcare providers

- Association of Sensory and Cognitive Impairment With Healthcare Utilization and Cost in Older Adults

- Over-the-counter hearing aids: What will it mean for older Americans?

- Addressing Hearing Loss to Improve Communication During the COVID-19 Pandemic

- Over-The-Counter hearing aids: How we got here and necessary next steps

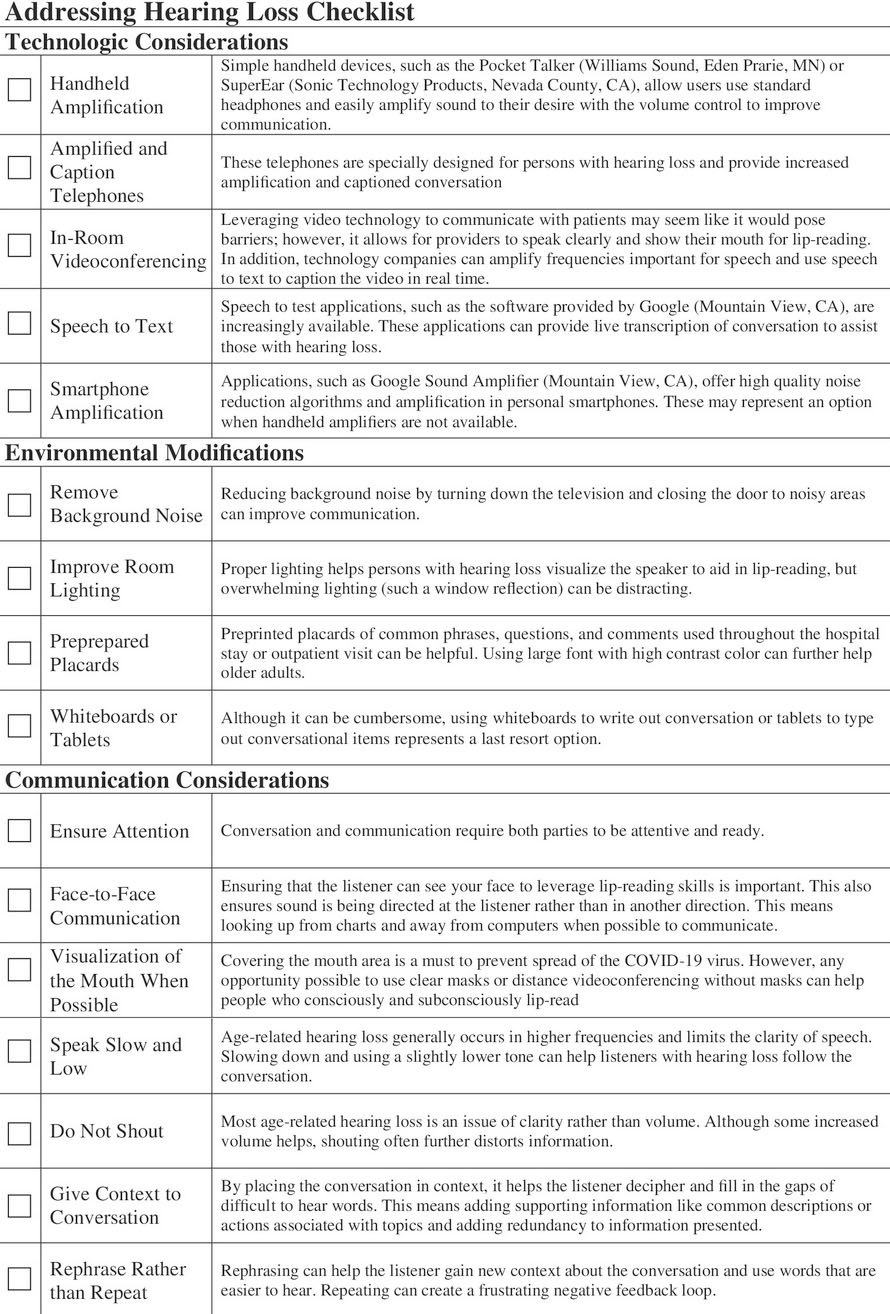

Lastly, I also just want to give a shout out to the last article above which also includes this lovely checklist of methods to address hearing loss in clinical encounters.

Eric: Welcome to the GeriPal Podcast. This is Eric Widera.

Alex: This is Alex Smith.

Eric: And Alex, I’m really excited today. We’re going to be talking about hearing loss in geriatrics and in palliative care. And we have two guests with us to talk about this.

Alex: Two wonderful guests. I’m delighted to welcome a friend, a research mentor, a colleague, a donor to GeriPal, Meg Wallhagen, who is professor in the UCSF School of Nursing. She’s passionate about issues related to hearing loss. She’s a former chair and board member of the Hearing Loss Association of America. Welcome to the GeriPal Podcast, Meg.

Meg: Thank you very much. Well, it’s really interesting being on this side of GeriPal rather than the other side, looking in.

Alex: And we’re delight to welcome Nick Reed, who is Assistant Professor in Epidemiology at Johns Hopkins University. And he is also a clinical audiologist, which is going to be key for this podcast. Thank you so much for joining us, Nick.

Nick: Thanks for having me. Super excited.

Eric: So Nick, before we dive into the topic of hearing loss, do you have a song request for Alex?

Nick: I do. How about Walk by Foo Fighters?

Eric: And why’d you pick that song?

Nick: Yeah, super personal song for me, but does have a hearing loss connection. Several years ago, a very close friend of mine passed away from Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome, unable to suppress tumors in his body. And the last thing we really did before he really took a turn for the worst was, we saw Foo Fighters concert together. So that band generally reminds me of Scott, but for not having tumor suppression at the end of Scott’s life, he also due to a tumor pressing up against his internal auditory canal, lost some of his hearing. And in those last few months of his life, he wore a pocket talker that I’m sure we’ll talk about today, these amplifiers, every single day. And it was his connection to his wife, child, and they would send me pictures and stuff. And this had such a profound movement on me that I actually like tore up a grant and rewrote my entire research line. And so for me, I don’t know, hearing and Foo Fighters just goes together. So, I know a long story, but you asked.

Eric: Let’s hear it, Alex.

Alex: And Dave Grohl, front man for the Foo Fighters and former drummer for Nirvana, who sings this song, has also talked about his own issues with hearing loss. So here we go, a little bit of Walk by the Foo Fighters.

Alex: (Singing)

Eric: All right, Nick, who did it better?

Nick: Oh, clearly Alex, definitely, right?

Meg: Right. That’s great. Wow.

Nick: Sounds great.

Eric: So I think this is our very first podcast on hearing loss, which is shocking. It’s such an important geriatrics topic. Although we’ll get into this, I don’t think it’s very much covered by palliative care curriculum. Meg, can I turn to you? How did you get interested in this as a topic both clinically and from a research perspective?

Meg: Well, to be honest with you, this was a long time ago. I’ve been doing some work, actually with the Alameda Chemistry looking at the data, and was looking at my own research. I’d been working with persons who had diabetes and also caregivers and so forth, trying to go at the direction and realize as I look more and more at hearing loss, that it was totally unrecognized in clinical practice. So I started asking around in terms of even my colleagues and so forth, you read about these little, like you say, paragraphs in books that say something about what you should do with hearing loss and testing for hearing loss, and making sure hearing aids are in place.

Meg: And they said, “Do you know anything about putting hearing aids in place or anything?” So it became really so pertinent to me that this was a humongous communication issue, and so many older adults just didn’t recognize their own hearing lots or didn’t acknowledge it. And nurses and other healthcare practitioners knew nothing about it. And so I wanted to see if I couldn’t do something from a very clinical perspective. So I totally turned my research into this area at a time actually, when it was so under-recognized and very unfunded. I had to convince nursing that it was even a nursing issue.

Eric: Thank you, Meg. Nick, how about you? How did you get interested in this from a clinical and a research perspective?

Nick: Yeah, totally different perspectives too, for me. Honestly, I grew up around hearing aids. My great-grandmother in particular had a very profound hearing loss and I don’t know, as a kid, I was obsessed with taking them apart and wanted to do more of the engineering side. And honestly in undergrad I was like, “Engineering is really hard. I don’t like this anymore.” And I switched to psychology and linguistics, and became this person interested in just speech. And somebody put in my head, “You should do audiology because you’re interested in hearing.” And I was like, “I never want to do that. I don’t see myself in that world.” I was actually a program coordinator for a high school at-risk youth program in Indianapolis, Indiana. And one of the parts of that was actually doing physicals for the students and putting them in job placements.

Nick: And we saw hearing loss in a significant number of our kids. We only had 300 in the program and there’s 10 with hearing loss. That doesn’t line up at all. And these are at-risk kids, they’re struggling in school. And I was like, “I want to do something about this.” And I went back to school, did audiology. Fast forward, I was doing pediatrics only, basically all day long at Georgetown University, had a random student fellowship, and I ended up at a poster next to Frank Lynn from Hopkins. He was an otolaryngologist and epidemiology person too, might have an appointment in geriatrics too. He is one of those superstars here. And he liked some of what I was doing, which was really on diabetes and hearing loss.

Nick: I was just peripherally interested in it, but he got really interested when I said, “Yeah, I’ve read some of your stuff. And I’m using these personal sound amplification products, these PSAPs for young adults who are in their mid twenties, transitioning off of their parents’ insurance, or they’re going to college and they no longer qualify for Medicaid as a child, and they don’t have hearing aids anymore. They grew up with hearing aids and they need something.” So bridging the gap, honestly, he offered me a job at a conference because we had posters next to each other. And now I focus on age-related hearing loss in just a completely different world.

Alex: Great story.

Eric: And let me ask both of you. So this is a podcast going at the geriatricians and palliative care providers. I actually pulled open a textbook on geriatrics. It has a whole chapter on hearing loss. I pulled open same size textbook in palliative care and had a small little paragraph that was a combined paragraph on hearing loss and vision.

Alex: Wait, which textbook had the small paragraph?

Eric: I’m not going to mention it. I may have been an author in one of the chapter.

Alex: Oh, okay. But the palliative care textbook had a small paragraph?

Eric: Palliative care one had a very… Yeah. Why is this important when caring for… Why it’s important for aging? What about for the palliative care listeners out there? Meg, what are your thoughts?

Meg: Well, you’re really addressing a problem that I’ve been proselytizing about for a long time. How do you have sensitive conversations with people about goals of care, if they can’t hear you? You think about the ways in which palliative care practitioners are taught to have sensitive conversations, to be sensitive to individuals, and yet it’s never raised in terms of addressing hearing loss. But individuals who have hearing loss, there’s several problems. One is, many people don’t even realize how much of a loss they have. But it’s not just a decrease in sound, it’s distortion of sound. And when you think about that, they’re hearing pieces of the information and their brain is trying to make sense of it. So, it’s very effortful, it’s very tiring when you have hearing loss to try and listen. And you’re bound to miss some information, but you’re also often left out of the conversation if the person feels that it’s taking too much time, they may talk to your partner instead of you, they don’t engage in the care, and we’ve done work with this and we’ve got some perspectives on the palliative care practitioners who acknowledge that they may misinterpret the person’s cognition.

Meg: They may think the person is not needing to be engaged or it’s going to take too much time. So they leave them alone. So, it’s a critical component if you really want to have conversations about goals of care, you want to have conversations about the types of treatments that the person wishes to have, or doesn’t wish to have, and to really engage the person and the family in these conversation. And that’s true across the spectrum of care, but it becomes increasingly important when you think about people with multiple chronic conditions, who really do have to make some of these very difficult conversations and decisions.

Eric: And hearing loss is associated with a bunch of bad outcomes. Is that right? Including more hospital utilization or healthcare utilization, maybe cognitive impairment issues. Is that right, Nick?

Nick: Yeah, absolutely. I think the one that gets all the attention is the dementia part. And there’s multiple survival analyses looking at incident dementia, and hearing loss is strong, independently associated with the time to event dementia. But when you put all those together, and this is what the Lancet Commission does, and this is what I think a lot of people take away and you start to do population level attributable risk for all the modifiable risk factors for dementia. And the non-modifiable risk factors is just genetics. And you pull that all out and hearing loss accounts for 9%. The easy way to interpret that based off of their models is, if you wiped out all the hearing loss in the world, you’d wipe out 9% of dementia. That assumes a lot, but I think that’s pretty amazing that of the modifiable risk factors, it’s the largest attributable risk, right?

Nick: More than obesity, more than education, that’s the one that people pay attention to. But then to your point on the other side, we’ve seen work that hearing is related to decline in gate speed falls. My own work focuses on hospitalization and health utilization over time. And we see things like over a 10-year period, adults with hearing loss have a 40% higher risk of experiencing a 30-day re-admission, 2.5 days longer duration of hospitalization if they are hospitalized, just spending, accounting for everything else under the sun we can think of, including baseline health and utilization metrics. They spend $22,000 more on average over a 10-year period. It’s a lot.

Eric: Why do you think that is?

Nick: I think it’s multifactorial-

Eric: Spoken like a good researcher.

Nick: Yeah. I think one thing I always acknowledge is, we’re never going to capture everything in launching of claims data or launching of surveys, right? There’s tons of people that you say you adjust for everything, but I’m sure there’s other things going on. So there’s always residual confounding, but I think it’s very much three pathways and it’s not understanding your care and then limiting treatment effectiveness and treatment adherence. I think that there’s stress and confusion during care, especially hospitalization leading to delirium, less satisfaction. And then there’s a synergistic piece here where when you’re not satisfied with your care, you don’t seek care in the future. If you’re not satisfied with your care and you’re ending up more likely to be readmitted, why would you look for care the next time?

Nick: And we’ve got some work showing that people with hearing loss, they don’t worry less about their health or anything like that. But if you ask them questions about, “Do you seek a doctor when you feel sick or do you disclose certain things to a doctor? Or do your perceptions of your care, absolutely different from other adults the same age?” Nothing about their own health. They worry, they care about their health, but they don’t engage with the healthcare system the same. So I think there’s this snowball effect over time and leads to preventable issues.

Meg: Yeah. I’d like to also bring it back to the personal level in terms of, I’ve had people share with me the issue of how prepared they need to be to go to a practitioner. Well, one, I talk to people and they always say the practitioner never asks about their hearing loss or takes it into account unless they have to self-advocate for themselves, if they’re aware of their hearing loss and they’re willing to self-advocate. But on that other level is that, it takes so much effort to hear what’s going on, especially have significant hearing loss. But on the personal level, it’s an engagement issue as well. We talk a lot about the issue of cognition and, yes, that’s a critical importance. But when you talk to people about relationships, the fact that they’re trying to communicate at church or any kind of house of worship, or go out to meetings, the fact that people stop going out to events, that they restrict what they’re doing.

Meg: I had someone talking about the fact that there were buildings they couldn’t go into, where they had to have tinnitus at the same time as the hearing loss, but that they just were very uncomfortable going out to any kind of meals or stuff like that because they couldn’t communicate. So they’re left out. So while we think about these other things, in terms of the cognitive stuff, the relationship stuff, the fact that engagement is so critical, is another humongous reason for taking into account hearing loss and paying attention to it, screening for it, which it doesn’t occur.

Eric: Well, how common is hearing loss in let’s say older adults? Or, do we know anything even how common it is, serious illness, palliative care populations?

Nick: I don’t know about that specific population, to be honest with you. But like just taking a big picture, if you use and he’s data, NHANES, National Health Examination Nutrition Survey, objective data, they actually measure hearing with pure-tones, the clinical goal standard. And if you look at adults or if you look at, I think everybody in the country, 20 and older, as of census a few years ago, you get around somewhere between 38 and 40 million Americans with hearing loss. But if you just look at some prevalence by age groups, once you get over the age of 60, half of all adults have a clinically meaningful hearing loss.

Nick: Once you get over the age of 70, it’s two thirds of all adults. And I’ll be honest with you too. If you pay attention to these things, which there’s no reason for anyone else to pay attention to this, but the World Health Organization has actually changed their criteria for hearing loss, and they’ve lowered the bar. And if you actually look at the numbers now, we went from two thirds of adults over the age of 70 to 97%. So, they’ve redefined hearing loss that it’s even more generous, if you will, the metrics here. So you’re getting to a point when almost everybody over a certain age just inevitably has hearing loss.

Eric: Well, that’s interesting, too. Meg, I’d love your thoughts, 10% don’t. What are they doing that I should probably start doing now? What’s going on with that 10% that are not having any hearing loss?

Alex: Stop listening to Alex Smith play Dave Grohl loudly. [laughter]

Meg: So, protect your hearing. Well, there is a genetic component. There are certainly a lot of environmental factors that go into causing, or at least contributing to hearing loss. One thing we’ve looked at a little bit, but it has not been well studied is the accumulation of ototoxic medications. I worked with a doctoral student at looking at that in terms of, because when we think of ototoxic medications, we usually think of high dose types of medications and certain ones. We certainly know that’s true of chemotherapy, that people who are post-chemotherapy again, often unappreciated and unscreened is that the ototoxic events of the chemotherapy leave them with hearing loss along with, even if they survive, which is great, but they have these other neuropathies and hearing loss along with it. But if you take a lot of the lower dose things around blood pressure medications and other things long-term, we don’t know enough about how much that affects hearing loss.

Meg: And there is some data that we looked at that suggested, yes, the incidence of hearing loss was greater in persons who had multiple types of drugs, even at lower doses. But people who don’t have it, one, maybe they didn’t go to a lot of loud concerts and so forth. They didn’t have the genetic exposures, but we still don’t know. And we do know that hearing loss is associated with a lot of other comorbidities. Nick raised the issue of diabetes, that for sure, and they’ve even come out with some criteria, but other chronic illnesses that affect cardiovascular system, cardiovascular disease, HIV, those kinds of things tend to be more commonly associated with hearing loss, which suggested if you have someone who has that kind of chronic illness, it’s especially important to do screen for hearing loss.

Eric: And how do we screen for it? What should I be doing as a clinician?

Meg: Well, I’d be pleased if you even asked about it.

Eric: Well, what do we ask? What’s the question?

Meg: You can ask, “Do you have difficulty hearing?” It’s better maybe to also say, “Has anyone ever told you that you may have difficulty hearing?” It’s helpful now that we have some other screens to use something we happen to test the finger rub, which we found, if it was standardized to be quite effective. Some people have advocated for the whisper it again, effect by noise, but increasingly there are also some apps on the cell phones and so forth that allow you to screen with various tones, and they are for persons themselves. We’ve been trying to use this. The WHO has what’s called the hearWHO, which you can do online and test your own hearing. And it’s using three digits in background noise, which is a pretty good way of testing for hearing loss. And it gives you an idea of how bad your hearing is, if you will.

Eric: And what’s that site? WHO?

Meg: Yeah. The WHO, it’s called the hearWHO.

Eric: Okay. We’ll have a link to that on our show notes.

Alex: It’s very punny.

Eric: Nick, when should we refer to an audiologist?

Nick: That’s a good question. I think the screening question to me actually to back up is a little bit of like, “Well, why are you screening necessarily? And what’s your goal here?” And I think from a practical standpoint, certain things just take too much time and the self-report questions, we know that people are not good self-reporters, but does that always matter as much? And so the one thing I’ll say about using self-report is, use a scale for example. And I actually use the NHANES’s question directly from that survey, and I use it for a very specific reason. And I’m happy to share it with your audience if you want to put a link.

Eric: What’s a survey question?

Nick: I don’t remember the exact words, but essentially it’s like, which statement best describes your hearing? And then it’s excellent, good, a little trouble, moderate trouble, a lot of trouble. And then they use the term deaf, which some people do identify as deaf, but deaf’s more of like a cultural identity. So not a lot of people will take that. But the point is that you give people an out to put themselves on a scale. And then they’re more likely, if you ask, to put themselves at a good or a little trouble, right? And actually start to give you some indication of where they fall. The other thing about using objective national or a nationally representative data set like that, the big things that actually affect how people self-report and hearing loss, men, honestly, if you put it all together, you use like a measurement error model, Caucasian, older males are the worst self-reporters.

Nick: They under report their hearing loss by the furthest degree, whereas actually relatively younger, 60 to 70-year-old black females are actually over estimators of hearing loss. And so you can take these things to account and realize that if a 90-year-old Caucasian male or nine-year-old male in general, race actually starts to play out with age at a certain point. If they say they have a little trouble hearing, or they say their hearing’s good, they probably have hearing loss. The odds are it’s there when you get to this rate. So, I like thinking of it like that. And then your question, what are you doing it for here? if you’re screening in the hospital for how you want to communicate or screening to improve communication and palliative care, for example, well, then your self-report question, I think is very meaningful.

Nick: You’re helping people in that moment in time. But if you’re doing it as an early screener for referring to audiology, the cut point may be different. And I think you actually want to ask people more of the kind of questions of how hearing loss is affecting their life, or this is where you want to put them in that, the hearWHO, or the Mimi app or the SonicCloud app, all hearing test apps and get people, talk to them a little about that baseline number and going audiology for that. Like, “What is your hearing number to a certain extent? Where do you fall on the scale?” And let that guide things. So this is like a deeper conversation of getting into hearing aids early matters and things like that. So I think there’s no perfect couple in here. I think it’s a certain question of almost after, at a certain age, everybody should get a hearing test.

Meg: Yeah. I think the one thing that I would just add to that though, and I really like the idea of a scale, and we’ve been trying to look at that in terms of capturing better data in a clinical setting that’s fast, it’s easy to do, but is also putting it in the context of health. I think what practitioners really need to do is emphasize so much that this is part of healthcare. So often what I’ve heard is practitioners discount the hearing loss or say, “Oh, I’ve been told I have hearing loss, too.” And it’s implied that somehow, well, you’re older, you’re hearing naturally it’s not going to be as good, but why shouldn’t it be? And the fact is that it is a health parameter, and it is related to so many health conditions. So valuing hearing loss, making the person understand why hearing loss and hearing in general is so critical to their overall health and wellbeing.

Eric: Well, let’s talk about what we can do about it. So, let’s say somebody’s screens positive. I’m going to start with communication techniques. I’m going to give each of you three, if you had to choose the top three things you wished clinicians would do when communicating with somebody with hearing loss, what would those top three things be?

Nick: That’s a good question. Can I plug my paper from January?

Eric: You can plug. Plug it away. It’s one of the top three. You can do whatever you want.

Nick: So I will always point people to, so my entire research line right now is about developing programs to address hearing in the hospital and what we can do about it. And we actually basically just published our training checklists for JAGS. And so we have, I think it’s, I want to say it’s just after COVID started, maybe June 2021 or something, and the article’s called Addressing Hearing Loss-

Eric: Post-mask era.

Nick: Yes. This post-mask era. Yeah. Addressing Hearing Loss-

Eric: [inaudible 00:28:21] mask era, like while we’re on mask.

Nick: Yeah. That’s a good point. It’s during, and we list here. I think we pulled seven communication considerations. We also talk about tech and environment, and I’ll only say my favorite ones. Meg, you feel free to chime in. But I think that the big one that people don’t understand and I have to get through to everyone is shouting doesn’t help at all. It makes things-

Eric: And why is that?

Nick: Hearing loss is a clarity issue. It’s not a volume issue. You lose your hearing at very specific frequencies, high frequencies, but you don’t lose it at low frequencies. And if you can imagine a regular word has multiple frequencies in it. So the low frequency part is still loud to that person and disrupts, and distortive. So, shouting, not helpful at all. Slow and low. And I literally mean-

Alex: Slow and low. That’s good. I like that.

Nick: Keep it slow. And when I say low, I mean when we speak fast and when we get excited, we tend to raise our voices and we get really high pitched and we do this and makes it worse. Most people don’t hear high frequency sounds. And the other one for me is actually, I think relatively simple for people, rephrase, don’t repeat. And I think people forget this, that we get these weird feedback loops that make everybody crazy and frustrated. Somebody says, “What?” And you say whatever, “Get milk and eggs.” And they’re like, “What?” “Get milk and eggs.” “What?” Rephrase it. “Go to the store, buy eggs. We’re going to have omelets for the breakfast.” Rephrasing is the only thing that can help. It adds context. It changes the words. If they didn’t hear it the first time, it’s not because they weren’t listening. It’s because they literally couldn’t access the information.

Eric: Great. Meg, what are your three?

Meg: Yeah. Well, I just want to echo the fact that, with the loss of the high frequency, it’s the continents. It’s what makes sense of the word, which is why people will also say you’re mumbling and so forth. And I laugh about the third time effect when people’s voices go up, and then all of a sudden you’re sounding angry. But I would say one is, face the person for sure. Make sure they can see your face, make sure the lighting is not behind you so it washes out your face, but in front so that the person can actually see your face. I know that’s affected by masks, but even being able to see the expression can be very, very helpful. So facing the person. Telling them when you change the topic so that you prepare the person for what they would like to hear, for sure.

Eric: So, putting things in context, going to the rephrasing.

Meg: Right. Yeah. Keeping the context. I like the one about rephrasing, because I do think that’s something that we overlook. And then, of course, I think just in terms of the communication strategies being really clear and asking the person if they understood what you were saying, make sure that the person almost like the teachback, but make sure the person did understand and ask them right up front. “Let me know if you don’t hear what I’m saying. I want to make sure that you can hear me clearly, and this is a noisy environment,” or whatever you can put it in context, but making sure and just reflecting on the fact that you want the person to hear you, and checking on that.

Eric: And where do personal amplification hearing aids, how does that all fit into this and whether we’re seeing people in their homes and clinics in the hospital?

Alex: Can I tell an anecdote here?

Eric: Yeah. Anecdote away.

Alex: Yeah. I’m on palliative care service right now. And so often we get consulted by teams that say, “I have this older patient and they’re pretty isolated and I think they have dementia. I wonder if you could engage their family in the goals of care discussion.” And we go see the patient and their heart of hearing, and we put a pocket talker on them and we start talking with them, and then we show the primary team and the primary team say, “It’s a miracle. It’s amazing. They don’t have dementia.” And similarly, today we saw patient in the ICU, critically ill, had some strokes, and the ICU team was saying, “He’s not interactive, less interactive.” Turns out the pocket talker was broken. But use a functioning pocket talker and suddenly, “Whoa, okay. He’s answering, yes, no appropriately.”

Eric: Nick, what’s a pocket talker for our audience that doesn’t know what that is?

Nick: So a pocket talker is the handheld amplifiers, as Kleenex is to tissues. It’s a certain brand of handheld amplifier, but we use it ubiquitously. So just keep that in mind though, if you look them up, there’s other brands, but a pocket talker is essentially just a very basic amplifier. It uses regular headphones that plug in just like you would on an old Walkman, Discman or something like that, if you’re referencing back to the ’90s or ’80s or before, I guess, I don’t know. It generally though makes all sound louder in a room. So it’s a great product for a static listening situation, very different from hearing aids, which are meant to be more like moving through dynamic situations.

Meg: I think the one thing that people need to realize about any kind of pocket talker, they do make very, very inexpensive ones. If you want to call the little personal amplifiers, you have to be really careful because these are not regulated necessarily. And you don’t want to put them on with the volume up. You want to make sure the volume is down all the way and put them on and then slowly increase the volume so that you don’t blow out somebody’s hearing.

Eric: Back to the slow and low. Start slow.

Meg: Right. Same thing with a pocket talker or a personal amplifier. But they all-

Eric: We give all of our geriatric fellows pocket talker or whatever they’re called. The more generic pocket talkers at the start of the year. I think we should probably do that with our palliative care fellows too.

Nick: The thing is though with pocket talkers, I know people don’t want to hear this, but there’s a certain downside to the pocket talker. We’ve turned them into this like cure-all miracle working pill. But when we talk about hearing loss, we just talked about how it’s frequency specific. And the pocket talker doesn’t do a great job. Even though it has some frequency settings, it doesn’t do a great job.

Eric: Has a little knob on the side often.

Nick: Yeah. People don’t do a good job of recognizing frequency. First off, like if you turn up the base on your car stereo, you notice it. You do the treble, you really have to be looking for trouble. Right? Clarity is different from volume.

Eric: I think one of the challenges though is when somebody is in your clinic or in the hospital, is that they often either their hearing aids are at home or there’s no battery in them.

Nick: No, you’re jumping ahead and you’re thinking, I’m saying something I’m not. Totally, the pocket talker are 100% phenomenal, but if you give it to someone and think that it cured hearing, you’re wrong. The bigger thing, and the more important thing is what we talked about a few minutes ago, which is the communication techniques. They’re going to go a million miles further even if you didn’t have a pocket talker, than the pocket talker alone. There’s a certain level of hearing loss where you have to have amplification. But the vast majority of hearing loss is mild in nature, and has a lot more to do with just being a decent communicator than trying to throw something at people. So for our research, we find that if you just use the pocket talker, people rely on it and they start to do things like just give it to people and think of a cured hearing. They turn around, they turn their backs when they talk to people. If we focus only on the communication, we get a lot better results in the hospital in terms of what our patients report.

Alex: Oh, fascinating. That’s really interesting, Nick.

Eric: So can we talk about hearing aids? We only have a couple minutes left, but you solved that problem. Right now hearing aids are over-the-counter. Everybody should have cheap access to them. Right, Nick?

Meg: No.

Nick: Yeah, no-

Eric: Are they over-the-counter yet? I see it like Amazon, you can buy hearing aids now, but then I see news reports, like FDA is still deciding what to do five years later. What’s going on there?

Nick: The big picture is there’s always been amplifiers out there that paint themselves as hearing aids, and the internet is still the wild west. So even though hearing aids were meant to be sold only through very individual practitioners, which is a policy dating back to the ’60s and ’70s really, when hearing aids were dangerous, truly dangerous in the hands of somebody that doesn’t know what they’re doing. The internet changed everything. And so, yeah, you could basically get a hearing aid on the internet or you could go buy one of those unregulated amplifiers that Meg talked about earlier. The OTC Hearing Aid Act is meant to a certain extent-

Eric: OTC, Over-the-Counter Hearing Aid Act, right? 2017.

Nick: Over-the-Counter Hearing Aid Act, 2017 rider on the FDA bill, bipartisan. Wonderful. It is meant to create a FDA regulated direct-to-consumer hearing aid path for mild to moderate hearing loss. So to a certain extent, you’re really empowering the word hearing aid as a label. So if you go to a store, those same things that you would see that are amplifiers and called personal amplification products, they couldn’t call themselves hearing aids, but they could market themselves for hearing, even though they weren’t supposed to. It’s not hard to get around those kinds of things. But if the word hearing aid is weaponized as a stamp of approval, that does give people some minimum trust in what they’re buying, whether it’s a cure-all though, for everybody getting hearing aids suddenly, that’s a different story, right? I think it’s a good thing. I think it changes competition in the market. I think it changes access points. I think it changes care. I think it changes the entire care model of audiology because it separates the services from the device.

Eric: Is that a good thing or a bad thing?

Meg: Well, I would argue that for several reasons, you really need good consumer education, where you’re talking about trying to give input on the incorporateness of labels. Because if people think this is a cure-all, it’s certainly not. People have to know what they’re really for. And that’s mild to moderate. I’m also still concerned that they’re going to be beyond the price range of many individuals, who we really wish to target. Because if you’re resource poor, you’re still not going to invest money in a over-the-counter hearing aid.

Meg: That’s not going to be one of your priorities. So maybe it will be something that will be used more by individuals who are fairly tech savvy and able to do the adjustments. But the directions for many of our older adults, they won’t be appropriate because, one, the hearing loss will be too extreme or too moderate to severe. But the other is that just from a manipulation standpoint, if you have any kind of dexterity problems, you may not be able to work with them. So yes, they certainly could be helpful and may get people into the market. But I’m hoping also that they don’t use it and find that they don’t like it very much. And then just not go to an audiologist or follow through and use other strategies to address their hearing loss.

Eric: But isn’t it a step forward? Hearing aids, you had six big manufacturers of hearing aids. Five big manufacturers.

Nick: Two of them merged a few years ago.

Eric: They’re 4,500 to $1,400. They’re you go to audiologists, they give you the ones that they’re working with. It seems like it’s ripe for disruption. I just looked at the Bose hearing aid. They’re calling it a hearing aid. Yeah. I figure Bose’s nice. It’s like $699. It’s better than 5,000.

Meg: That’s true. But the fact is that unfortunately, what you’re seeing in so many situations is that’s a bundled cost. They’re pricing their services and you’re paying for the hearing aid along with the service. There are efforts to unbundle stuff and to have you know exactly what the price of the hearing aid is, versus the price of the service. And that can help at least have you understand that it’s not necessarily the hearing aid costs all that money, but you’re actually paying for the fact that, that audiologist is going to be doing all the hearing fitting and so forth.

Meg: What’s sad about that is that often because they’re needing to have you purchased the hearing aid along with the service, is that they don’t do the oral rehab. And I think that was what Nick was referring to too, is that hearing aids are aids. They don’t cure the hearing loss. You have to learn to work with them. Your brain has to relearn how to listen. You’ve got to use them, but you need to also use really good communication strategies along with them and relearn how to do that. Because often people have had hearing loss for quite some time before they even go to get hearing aids or other kinds of services.

Nick: Well, part of this though, is that, yes, in the immediate future, disruption is sometimes rough. And I do actually have worries. I don’t think this is a cure-all. I think there’s many more things we need to do. I actually worry about our Medicaid population. When things go over-the-counter, Medicaid doesn’t exactly want to cover it anymore. It suddenly changes the model. So something that used to be covered by Medicaid, even though it’s cheaper on the open market, may suddenly not be covered by a Medicaid. And that’s not something people are going to access, right? But in general, to your point, Eric, it’s a disruption where the current model is very low volume, high cost integrated. You almost have a gatekeeper model. People think I’m saying that negatively.

Nick: I’m not. It’s just the model of care. I love the idea of getting hearing aids separated from me as an audiologist, because right now the only thing anyone sees is that $4,700, whether bundled or not, they darn well don’t see my services. They see the cost of a hearing aid and they think I’m just some separate sort of car salesman. But in reality, I’m a mechanic and a mechanic is a great thing to have, a good mechanic, right? Everybody wants a good mechanic. Everybody forgets about their car salesman. I don’t want to be seen as the person who sold you a hearing aid and that’s all I’m associated with. I want to be seen for my skillset. And so when we separate the device from the services and make them separate unbundled purchases, not a bad thing, and this disrupts the entire flow, right? We get new competition. Bose may be expensive, but Bose won’t be the only one to get involved.

Nick: Some people will jump in and be at a different price point. I guarantee there’ll be a more expensive ones. There’s always people who are going to buy Lexus. And over time when you align and realign this device with the consumer and you don’t have someone in between anymore, this changes what the companies make and do. So hearing aids right now, it’s somewhat of a false logic when we apply current hearing care models to OTC, because the OTC devices won’t look necessarily and always be the same as current models. Right now, a hearing aid company, they advertise to me because I choose the hearing aid, right? They advertise audiologists. You flip the switch, you get rid of that person. And suddenly the hearing aid companies are making things for someone in the end. And we might see some crazy innovation actually that works for older adults, right?

Nick: We may see almost like a flip back to devices that are easier for people with finger numbness or dexterity issues that are easy to put in. I love these concepts of where we can go, but please don’t get me wrong. I do think it will be a rough picture for some people. And I do think in the immediate future, it’s going to be hard, right? It’s not easy, but change is never easy. And sometimes it’s a good thing to kick up a system that has basically been operating the same way since the 1940s and ’50s when audiology was founded.

Alex: And since, was it ’70s when Medicare legislation came to be, and they explicitly prohibited inclusion of hearing aids and coverage under Medicare policy, right?

Nick: Alex, I’ll be honest with you. I’m very biased here, but my personal thing is that OTC hearing aids are never going to fully succeed, the whole concept of it, until we get Medicare coverage for the audiologist. And you have this services are covered. You have a world where… And I don’t mean just hearing aid coverage under Medicare. I literally mean cover audiology services. People can go by hearing it on the open market. Let that do its thing. But build in safety nets for Medicaid and build in services. You can go to an audiologist four times a year, for example, they can help you with whatever product you bought. Right? You buy it on the shelf at Walmart, great. Bring it to me. Again, I know people hate it. They hate the mechanic and car analogy, but cool. You buy Lexus, you don’t need me? Sure. You bought a Hyundai. Buy a driver Hyundai Accent. No offense to Hyundai, but I need a good mechanic.

Alex: GeriPal is sponsored by Hyundai. I was just kidding. [laughter]

Eric: Okay. We’re wrapping up. I have a lightning round question. Two of them, actually. I don’t know if Alex does. I mainly see people in the hospital. I also sometimes see them outside of the hospital. And they’re putting in their hearing aids. It doesn’t seem to be working. We finally give up, we put on the pocket talker. Is there a way to figure out whether or not… How long do the batteries last, and how do you figure out if they’re actually on? Especially in people with some cognitive issues, they’re fumbling.

Meg: Well, the batteries actually don’t necessarily last all that long. And it depends on what the hearing aid is doing, because if it’s using Bluetooth, it’s using its batteries faster.

Eric: On average, one to two weeks or less than that?

Meg: Well, it’s not even that long at times, depending again on how well they’re used. And probably Nick has some other ideas about how it is, but one of the things you can turn it out and hold it in your hand and just see if it squeals partly because of the feedback, if the battery’s working-

Eric: So, bring them together?

Meg: Yeah, right. Or, just put it in your hand so that it gets the feedback in the hearing aid. And you’ll hear it squeal if it’s working. It may be clogged with wax. That’s one of the not uncommon factors to do, and checking to make sure the battery’s in place. And as you are obviously asking, of course, that assumes they’re bringing new batteries with them.

Eric: Great. Next lightning round question for me, cochlear implants, we can have a whole other discussion. Anything I should know as a clinician when caring for somebody with a cochlear implant?

Meg: Well, depends on whether then, again, I’m sure Nick will comment on this, but the issue is that if it’s one sided, usually right now they are changing the strategies, but that little tiny wire goes right into the cochlear. And it tends to destroy the hair cells that are there, which means that when you take that cochlear implant off, the person can’t hear. So they take them off at night or whatever, the person is basically unable to hear it all. They may have a hearing aid in the other ear and sometimes they have bilateral cochlear implants. But also just to know, is that the person themselves, when you’re thinking about it is that they have to learn a whole new way of listening because they’re not using their hear cells. This is an electrical stimuli of the nerve. So the person who gets them has to relearn how to hear with this new type of sound. And you have to work at it, for sure.

Nick: Very difficult uphill process. If you happen to know when your patient got their cochlear implants and it’s not been over a year even, or even a few years out, they may still be in the throes of that rehab period, or they may have peaked there, to be honest with you. It’s not easy for older adults to necessarily get used to the cochlear implant. It really is a totally different listening.

Meg: Right.

Eric: Alex, do you have any other questions? I want to thank both of you for joining us, but before we end, we’re going to actually turn to Alex for a little bit more Foo Fighters.

Alex: (Singing)

Meg: Wow.

Nick: That was awesome.

Alex: Hopefully nobody lost hearing. [laughter]

Meg: No.

Eric: Well, Meg and Nick, big thank you for joining us.

Meg: Well, thank you so much for your interest in hearing loss.

Alex: Thank you so much.

Eric: And we’re also going to have in our show notes, we’re going to have links to the articles that we referenced here, including Nick’s new JAGS article that’s coming out on over-the-counter hearing aids. And also, where was the one about the hospital?

Nick: Also JAGS addressing hearing loss, I think, during the COVID-19 pandemic. I can’t remember my own title. I’m sorry.

Eric: Great. We’ll have links to that too. And with that, big thank you to Archstone Foundation for your continued support, and to all of our listeners.