by: Jessi Humphreys, MD (@jessi_humphreys)

Across the world, millions of individuals, largely from developing regions, suffer and die in pain, with no access to palliative care services or pain relief. This includes 2.5 million children dying annually with serious health-related suffering. This is inexcusable. We must intervene on this well-demonstrated inequality. Moreover, fixing this problem would be surprisingly cheap.

In the past, global health initiatives have had many key priorities: maternal and fetal mortality, immunizations and infectious diseases among them. The importance of these areas cannot be overstated (remember the damage that polio and small pox caused!). Global palliative care is one of the newest priorities. With increasing energy dedicated to chronic and life-limiting illness including oncologic disease, health care providers discovered that globally we lack the supportive care and pain relief to enable quality treatment of these diseases. In 2014, the WHO published the first-ever global resolution identifying palliative care as a core component of a well-functioning complete health system1.

In preparation for World Hospice and Palliative Care Day on Oct 14, the Lancet released a commission: Alleviating the access abyss in palliative care and pain relief – an imperative of universal health coverage.2 This hot-off-the-press report presents the current burden of palliative care needs, the cost required to intervene, and recommendations for moving forward. It estimates that in 2015, 45% of deaths worldwide experience health-related suffering and a need for palliative care and pain relief. However, ~70-85% of patients lack access to these services. In other words, up to 38% of patients worldwide die in pain.

As opposed to looking at outcomes such as morbidity and mortality, the report measures the global burden of severe health-related suffering, which is illness-related suffering that compromises physical, social or emotional functioning. They also introduce the concept of a SALY (suffering adjusted life year), in contrast to a DALY (disability adjusted life year) or QALY (quality adjusted life year). This shifts the narrative, framing global palliative care and the alleviation of suffering as an ethical imperative, independent of economic outcomes. From the perspective of human rights, all individuals deserve the right to die with dignity, even if there is no financial gain. There are also economic arguments, and hypotheses that patients with less suffering have the ability to contribute more, but this is not what drives our responsibility to right this inequality.

The primary recommendation of the report focuses on the lowest-cost essential palliative care package that could alleviate suffering. This package includes key medications, basic equipment, and human resources that would be required for the delivery of care.

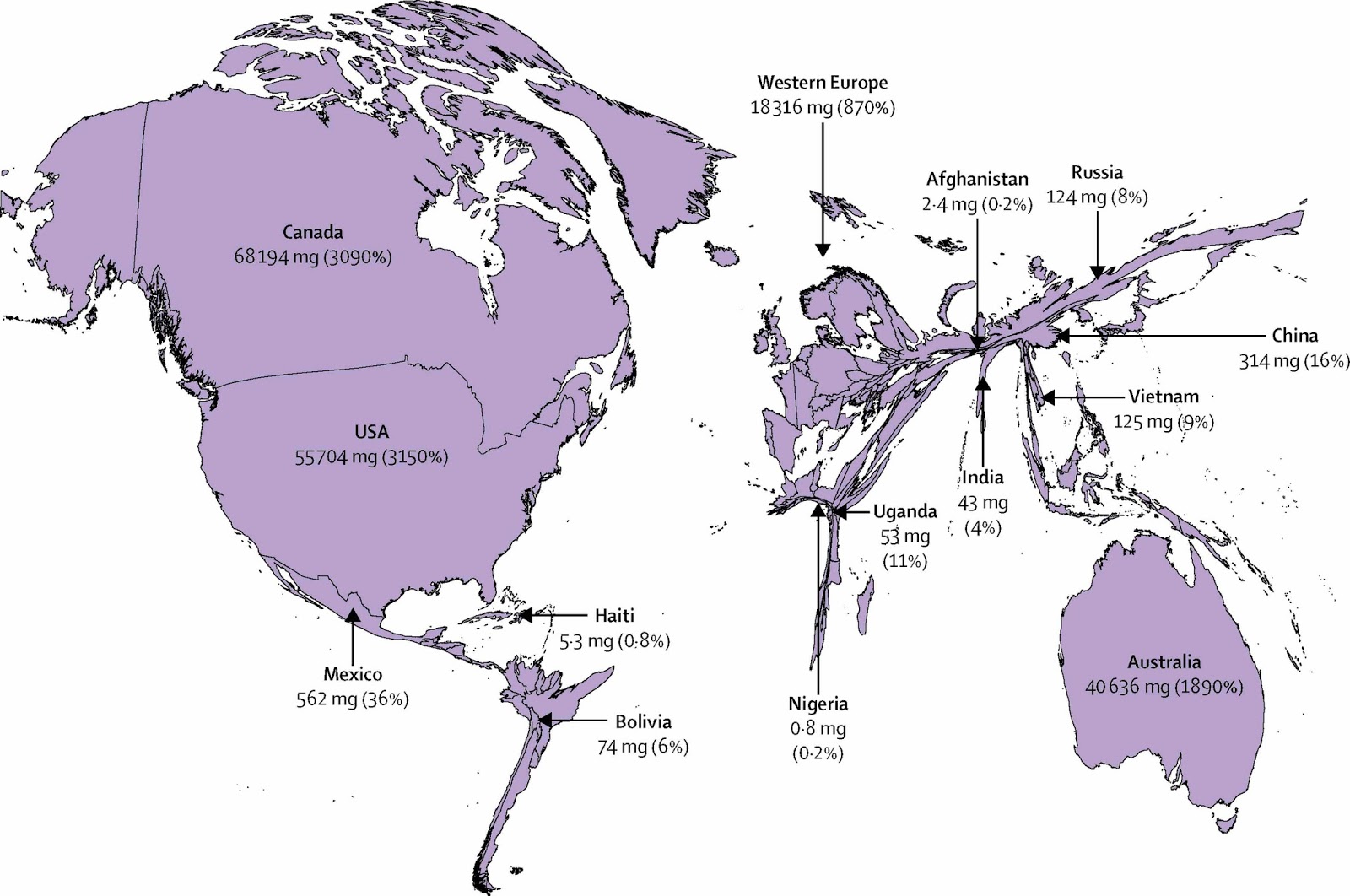

Considering that the majority of patients in need of care in this study had suffering related to pain, access to morphine was a primary focus for intervention. In studying over 170 countries, of the roughly 300 metric tons of oral morphine equivalent,

Oral morphine is off-patent and cheap; it is estimated that one million dollars per year would provide adequate pain control to all children under 15 years-old in the world. Meeting the global opiate shortfall for children and adults would total $145 million (assuming a price discount that has been gifted to wealthier countries). Lower income countries are frequently sold medications at higher costs as compared to their higher income cousins. These costs, however, are uniformly low when compared to the $12.8 billion in global health aid the United States contributed in 2016,3 or the $100 billion the world’s governments spend on enforcing drug prohibition annually.

Other than economic concerns, the barriers to morphine access within low and middle income countries are largely legal and systemic. Many countries do not legally allow patient access to morphine, and often only allow access to morphine in the hospital. As a result, patients may have access to pain control in the hospital, but then are sent home to suffer and die in agony.

Underlying the systemic and legal barriers is what has been called an “opiate-phobia,” a deep-seated fear about potential misuse of opiates, fed in part by the visible opiate epidemic in the United States. It is assuredly wise to be mindful of excessive opiate use and have systems in place to prevent opiate misuse. However, in developing countries where access to morphine has increased in conjunction with improved palliative care, we have reassuringly not seen a concomitant increase in opiate use disorders. Uganda serves as an encouraging success story. Advocates overcame legal barriers and enabled mid-level providers to prescribe opiates. Through extensive policy change, and widespread education, they created a network of outreach services and revolutionized their delivery of palliative care services, largely to patients in their homes.

As a call to action, the commission proposes a multi-pronged approach characteristic of global health initiatives. It calls for increased nursing and provider training, improved access to off-patent affordable oral and injectable morphine, and the recognition that an integrated, comprehensive, and universal health coverage system must include palliative care.

This commission reminds us to be angry, and hopeful. It is appalling that millions of people die in pain, and that this suffering is disproportionately layered on those living in poverty. It is striking that only one million dollars would allow children globally to die without pain, while Americans spend nearly 3000 times this amount on Halloween candy annually. But we are also uniquely empowered and able to close this gap in inequitable palliative care and pain relief. This is one of those diminishingly rare opportunities where solving a problem would be both ethical and affordable. We need to get to work.

References:

- WHO | Palliative Care Fact Sheet. WHO Palliative Care Fact Sheet. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs402/en/. Accessed October 24, 2017.

- Knaul FM, Farmer PE, Krakauer EL, et al. Alleviating the access abyss in palliative care and pain relief—an imperative of universal health coverage: the Lancet Commission report. The Lancet. October 2017. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32513-8.

- Financing Global Health 2016: Development Assistance, Public and Private Health Spending for the Pursuit of Universal Health Coverage. http://www.healthdata.org/policy-report/financing-global-health-2016-development-assistance-public-and-private-health-spending. Accessed October 24, 2017.