Although I usually think with my stomach, I have been particularly preoccupied with how we feed our most vulnerable elders this week. That’s because my Home Based Primary Care team took up the #ThickenedLiquidChallenge in order to raise our awareness of what we put our patients through. The challenge is admittedly biased to make one hate thickened liquids. Participants have to thicken everything they drink with corn starch until it resembles honey in consistency. Those of us who have fed these products to our patients are well aware that “nectar-thick” liquids are much more palatable (i.e. less disgusting).

It has been fascinating to watch a transformation take place as we accept the challenge. Our dietitians are speaking up in team meeting. They are questioning whether or not thickened liquids are consistent with our patients’ goals and wishes. We care for patients at home, so we are well poised to ask this question. HBPC can even bring a provider and the RD out together on a house call in order to discuss the lack of medical evidence about risks and benefits. More importantly, we can sit in the kitchen and address what we definitely know about the burdens of gagging down thickened liquids and the burdens of attempting to enforce a “chin tuck” when feeding thin liquids to a person who has dementia. This is not just patient centered care, it is family centered care.

I’m also a nursing home doc who has taken care of SNF patients for a decade, so I was delighted to see that this week’s Journal of the American Medical Directors Association (JAMDA) has published a special research agenda to improve food and drink intake in nursing homes. It was even more exciting to see an exhaustive literature review of the research, such as it is, about increasing fluid intake and decreasing dehydration. They found modest evidence that dehydration was reduced when nursing home residents had a greater choice of things to drink, when staff were made aware of the need to encourage fluids and became more involved assisting with drinking and toileting. Not surprisingly, it concludes with a plea for well-designed studies.

Getting back to the thickener question, we need well-designed studies that examine quality of life, incidence of pneumonia, and hydration status before and after we choose to abandon thickened water.

Qualitatively, I can tell you that my patients with dementia so severe that they were wheelchair bound appeared much happier when liberated to plain water. So did the ambulatory patients. Shoot, so did everyone. And the only significant aspiration I’ve ever witnessed involved a desperate theft of a big hunk of meat from a neighbor’s plate. To be fair, giving plain water carries burdens for help dysphagic patients to drink. After 15 minutes of saying “tuck your chin” before every swallow, I get twitchy with frustration, yet that is what is needed to reduce coughing and sputtering. If I had to choose between my own impatience and my patients’ happiness, I choose their happiness. No question.

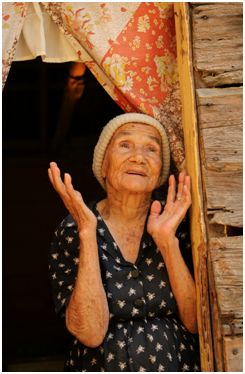

At the end of the day, food is love. Drink is no different. It hurts us in subtle ways when we force people to eat and drink the things they hate. We often demonstrate affection through the food and drink we give to those who we love. When the Speech Pathology report comes back showing high risk of aspiration, we should put that love on the table as we discuss goals of care and the burdens of treatment.

by: Theresa Allison

Note: This post is part of the series on the #ThickenedLiquidChallenge. To watch the videos of this challenge go to our original post here, or check out the videos on YouTube:

- The Hospice and Palliative Care Team taking the challenge

- Alex Smith taking the challenge

- Eric Widera taking the challenge

- Dawn Maxey taking the challenge

- Ken Covinsky taking the challenge

- Allen Tong taking the challenge

- Mike Steinman taking the challenge

- Nancy Lundebjerg taking the challenge

- AAHPM staff taking taking the challenge

- San Francisco VA ACE team taking the challenge

- Christian Sinclair from Palmed taking the challenge

- Suzanne Gordon taking the challenge

- Home Base Primary Care taking the challenge

- UCSF Interprofessional Geriatrics and Palliative Care Elective taking the challenge

- Gigi Trabant taking the challenge

- SFVA iPACT team taking the challenge