Hospice may not be a great match for all of the care needs of people with dementia, but it sure does help. And, as often happens, when patients with dementia do not decline as expected, they are too frequently discharged from hospice, an experience that Lauren Hunt and Krista Harrison refer to in an editorial in the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society (JAGS) as feeling like being “expelled.”

We talk on this week’s podcast with Elizabeth Luth, author of a study in JAGS about her study of patients in a large New York Hospice with dementia who either are discharged from hospice or live longer than 6 months. Turns out this happens – brace yourselves – nearly 40% of the time!

And we talk with Elizabeth and Lauren Hunt, who helps us contextualize these findings in the setting of larger issues around the fit of hospice for persons with dementia and hospice Medicare policy.

We will add the link to the editorial when it’s uploaded to the JAGS website.

-@AlexSmithMD

Eric: Welcome to the GeriPal podcast. This is Eric Widera.

Alex: This is Alex Smith. Oh, I almost didn’t come in.

Eric: That’s what I was going to say. You’re going to join us?

Alex: That’s happened before.

Eric: Alex, who are our guests today?

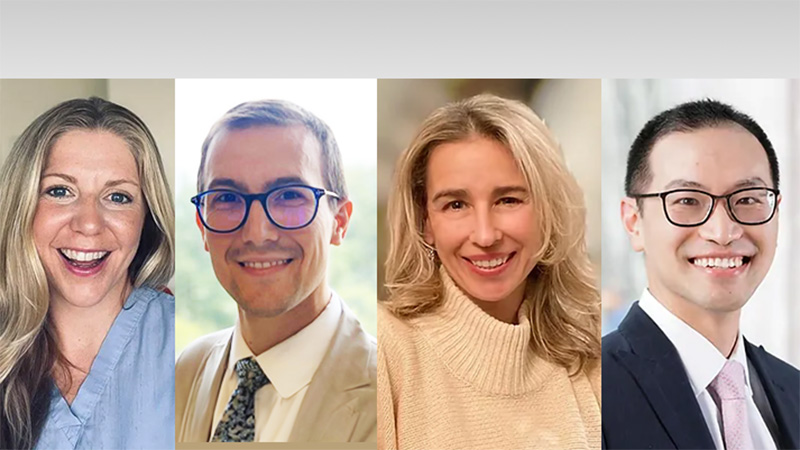

Alex: Today, we are delighted to welcome Elizabeth Luth who goes by Libby. She is a post-doc at Weill Cornell in Geriatrics and Palliative Care. Welcome to the GeriPal podcast, Libby.

Elizabeth: Thanks for having me.

Alex: And we have Lauren Hunt who is an assistant professor in the UCSF Department of Physiologic Nursing and a Senior Atlantic Fellow in the Global Brain Health Institute. Is this your first time on the GeriPal podcast, Lauren?

Lauren: I think it’s my fourth. [laughter]

Alex: Okay. Yeah. Why did I think it was your first? [laughter]

Lauren: Glad you remembered [sarcastically] [more laughter]

Eric: Alex is on Service. I heard Service is busy, so I’m going to give him a pass. [laughter]

Eric: We’re going to be talking about ‘Survival in hospice patients with dementia’, an article that Libby came out with just recently. It was published in JAGS, I believe.

Elizabeth: It was either end of January, beginning of February. Yeah.

Eric: And an accompanying editorial by Lauren and Krista Harrison titled… And I love this. I love this title. I think it’s really important to talk about, how we use words… ‘Live Discharge from Hospice for People Living with Dementia Isn’t Graduating, It’s Getting Expelled’ We’re going to be talking about both of those but before we do, you got to sign a request for us. Who has a song request?

Elizabeth: I do. I do. I’d like to request Landslide by Fleetwood Mac.

Alex: Why this song?

Elizabeth: Well, first: because Fleetwood Mac. I’m dating myself, but they’re a great band. And because I think it does a good job of sort of alluding to some of the issues with how people change and dementia and lose themselves relationships change over time and thinking about what happens with loss at end of life.

Alex: Yeah. Great choice. I think I’ve done it before, but I’m always excited to try a re-do.

Eric: Alex remembers the song, but not the guest. Uh-oh. [laughter]

Alex: Alright, here we go.

Alex: (singing) I took my love, I took it down . I climbed a mountain and I turned around. And I saw my reflection in the snow-covered hills . Till the landslide brought me down.

Eric: Wonderful. Thank you, Alex. Did you like this version better or the last one, Alex.

Alex: This one. Yeah, definitely. I think last time I didn’t finger pick it correctly, so. I appreciate the opportunity to learn these songs and hopefully they get better with time not worse.

Elizabeth: I thought it sounded great.

Lauren: Beautiful.

Eric: Let’s dive into it. Again, topic around hospice patients with dementia. Libby, how did you get interested in this subject?

Elizabeth: So, I’m interested in for two reasons. The first is that my grandfather died of Alzheimer’s and my grandmother was his caregiver for over 10 years, the sole caregiver for over 10 years, and so there’s a personal angle. The other is that I’m a sociologist by training so I am not a clinician and sociologists like to understand sort of patterns and what happens to folks and why. And death is the one thing that happens to everyone. You can’t buy your way out of it. It doesn’t matter what color your skin is. It doesn’t matter what sex or gender you are. And so when I went back to get my PhD in sociology, I knew that I wanted to study end-of-life care and the outcomes at end-of-life. So, this is sort of the intersection of the two.

Lauren: Death and taxes. [laughter]

Elizabeth: Death and taxes. In fact, I have a slide. Why this? The slide has a picture of a quote from Benjamin Franklin.

Eric: My wife is a trust and estate lawyer and I do palliative care and hospice. So we always thought about opening up a shop right next to each other could be called Death and Taxes. [laughter]

Alex: Lauren, how about you? How’d you get interested in this topic?

Lauren: So my interest is, was really born out of my clinical experience. I worked for a number of years as a hospice nurse. And my experience was… I was taking care of all of these patients. Almost half of my patients had dementia. I was surprised to learn that when I went in, to go in and working as a hospice nurse, and this is my personal clinical experience, but this is also now just coming out in the literature that almost half the people in hospice have dementia.

Lauren: So, I was taking care of all of these people with dementia. And I just felt like the way the hospice benefit was set up for people with dementia was really not working with them. And one of the issues that I saw was people with dementia having these long enrollments that then ended with these really disruptive live discharges. And I worked as a nurse practitioner doing face-to-face visits. Some people would dread my visits because I would sometimes have to go and tell them that they were no longer eligible for hospice. And so then, we were taking away all of these services. So, this was really driven my interest in this area, my research focusing on this topic.

Eric: And how about we turn to the article or just talk a little bit about kind of what did you do and Libby, what did you find? So, first of all, what brought you to kind of doing this article and, and how did you do it?

Elizabeth: Right. So we looked at the electronic hospice record for a large New York city hospice provider over a five-year period. And we had access to all of the records. And we looked specifically at patients who had either a terminal dementia diagnosis or a comorbid dementia diagnosis. And that gave us about 4,000 patients over a four year period. And what we wanted to look at was sort of a combination of a couple of things, like one: what are N-related. So one is what our outcomes that hospices themselves are interested in long length of staying in live discharge or things that clinicians are worried about. Lauren spoke about her experience. The hospice administrators are worried about it, because the second thing that we were interested in was looking at sort of the hospice policy and the Medicare policy, and the reason administrators are worried about it is because those things get measured and they get measured by CMS and through PEPPER reporting guidelines.

Elizabeth: And so we wanted to see what’s going on with these folks with dementia in terms of their experience of hospice as intended. And I use quotation marks around that because of course, individual’s experiences are very different over time and care plans and hospice respond to those changes and are individualized. But from a regulatory standpoint, Medicare expects that, you go into hospice with enough time to get benefit from it. So you don’t go in and die later that day and that you receive the benefit for no longer than six months or 180 days. And so that’s what we really wanted to say. We really wanted to look at, it was like, what’s happening with folks with dementia who are receiving care for longer than a week so maybe they’re getting some of the benefit and what happens after that. Are they dying within the six months that Medicare says that they should die within ideally?

Alex: So you had a joint outcome in this study of people who were discharged alive from hospice, or who lived longer than 180 days, half a year. Is that right?

Elizabeth: Yes, exactly. So we compared people that died within six months to people that either had a long length of stay, longer than six months, or who experienced a live discharge.

Alex: Can you tell us more about… Oh, go ahead, Lauren, you look like you’re going to ask a question.

Lauren: Oh, well, yeah. I was interested in that as somebody who’s, who’s working on a similar study and struggling with these issues, why you decided to go with that approach as opposed to parsing out these different outcomes?

Elizabeth: As opposed to having like separating long length of stay and live discharge?

Lauren: Yeah. I was just curious about what your thought process was around that, or if you guys had considered different alternatives.

Elizabeth: Yeah. So, one of the reasons that we chose survival analysis as the method, which required that we group the long length of stay in live discharge together was that we wanted to be able to look at how nurse visits or patterns. We were particularly interested in the relationship with the timing of nurse visits and how those were pattern relative and what influence or association they had with whether somebody died within six months or experienced an unexpected outcome.

Alex: And conceptually, you are also thinking of these both things as poor outcomes, like outcomes that are not desirable from the perspective of the hospice who enrolled these patients in the first place. Is that kind of an idea?

Eric: Probably from Medicare, right?

Alex: Perspective of Medicare, who’s paying the hospice who enrolled these patients in the first place. I think it’s important to get, yeah.

Elizabeth: Hospice they provide the best care to patients that according to what the patients need, right?

Eric: They help, yes.

Elizabeth: So they are not driven by the six months or the live discharge. You know, this is a… I mean, of course there’s a variety of studies around this. This is a non-profit hospice. So they are not that creates a slightly different context than the vast majority of their characters in the community setting, as you can see from the descriptives. So they’re not a nursing home that also is a hospice, so they’re sort of particular drivers. Yeah. So, but from a Medicare perspective, whether you’ve got a long length of stay or a live discharge, it’s not good.

Lauren: Well, I think this issue of perspective is really interesting. Cause I think the long enrollments are definitely… from the Medicare perspective, that’s a bad outcome for Medicare because that means they have to pay more money, right?

Lauren: At least under the old system… I mean, this is at least the way I kind of been thinking about it, but live discharge is… I mean, the long enrollment isn’t necessarily a bad outcome from the patient perspective, right. Because they are getting all those services all the time. I mean, it’s really, it’s a theory, but then live discharge from the patient perspective is definitely a bad outcome because then they’d lose the hospice services and Medicare is concerned about quality.

Elizabeth: Right, so I’m going to play devil’s advocate and I have not run the numbers on this, but I do know that the outcomes for people that are discharged alive from hospice aren’t great, right? They tend to end up in the hospital, which Medicare pays for. It is expensive, much more expensive than keeping somebody in home hospice.

Elizabeth: They often die within six months of being discharged, which indicates that they could have benefited from continuous hospice care if they had remained continuously enrolled. And there are these transitions between care settings that often result in sort of intensive and expensive care. So I would posit that it possibly continues to cost Medicare money. The other is, is that even with these long lengths of stay, if folks are continuously, hospice is a relatively cheap form of end-of-life care, relatively cost-effective compared to nursing home stays, compared to hospitalization and long-term care facilities. So yes, they’d be more under the hospice benefit, but whether they pay more overall for the care of that individual, the healthcare of that individual over time, I think is up for debate.

Eric: Because a lot of what we’re thinking about hospice and Lauren, I think you’ve mentioned this in your commentary is that this was a benefit that was created, what, in the eighties? When we were really just about cancer, HIV and the trajectory of both of those have changed significantly. And we are enrolling other people with non-cancerous conditions like dementia, where it just doesn’t follow that same curve. So even looking at, from a financial standpoint, it doesn’t make much sense in really either case. There was a really lovely article. I was just reading from Joan Tino called ‘Financing the Care of the Seriously Ill — “Hell No, I Won’t Go”’ that was published in JAMA forum. We’ll put a link to it on the website.

Alex: Hell No, I Won’t Go?

Eric: Hell No, I Won’t Go.

Lauren: Another good title.

Elizabeth: Another good one.

Eric: That came from a patient experience, a case she actually talked about where somebody said, “Hell no, I won’t go” after being enrolled in hospice and actually disenrolled.

Alex: Is it “Hell no, I won’t go. I won’t leave hospice” or “Hell no-

Eric: No. “Hell no, I won’t go. I won’t stay in hospice.” Yeah. But anyways, thoughts on that. Thoughts on the generalizability of hospice that was great in the eighties to what we’re dealing with now?

Elizabeth: I think it’s a different beat and we know that government is the last institution to sort of be able to have the slowest to respond, to changes and realities on the ground, but you’ve got different patient populations with different end-of-life trajectories. They all have to meet the same eligibility criteria in order to be enrolled in hospice, whether they have cancer dementia, but it’s, you have to… and the other thing too is that the six month benefit wasn’t based on the clinical trajectory of that post with advanced cancer or HIV, it was based on sort of what was available on the budget at the time. So now that you’ve got a completely different patient population, it makes you sort of wonder, “Do we need to rethink some of the time and some of the…?”

Lauren: Yeah, I mean, I think I completely agree. And I think hospice was originally designed for an advanced cancer and HIV model, and it still has not caught up to the current situation where the majority of patients in hospice now do not have cancer. And people with cancer, it’s advanced cancer, it’s relatively easy to predict when what their prognosis is, but it’s notoriously difficult to predict in, especially in dementia. And Alex is hard at work on trying to make better models.

Lauren: The other thing that I wanted to add is an addition to a change in the patient population over the past 20, 30 years, there’s also been a really big change in the hospice marketplace over the past 20 years. So it used to be that the hospice organizations for mostly non-profit. There was a lot of volunteer involvement. And now, hospice is a multi-billion dollar industry and there’s been a shift in the total number of hospices in the industry so it’s gone from one to 4,000 in the past 20 years. There’s been a shift from predominantly non-profit to for-profit. I’m on this hospice industry newsletter, I get these updates daily. It’s like this company merged with that company. Private equity is bullish on hospice. So, that has accompanied a lot of these changes in patient population characteristics. And what is motivating hospices in enrolling and providing care for patients.

Eric: Yeah. And if you’re beholden to shareholders or to stay in the black, then part of your goal is potentially enroll patients that are going to be a steady stream of potential income that aren’t going to require a whole lot of resources. And that will be on the books for a while and potentially leading to a very long length of stays. I think targeting diseases like dementia, where the people with very advanced disease can be alive for a year and a half for two years. There is uncertainty around prognosis. It does decrease significantly beyond that. And it sounds like Libby, that’s what you were saying too around, yeah, just because they also graduate from hospice doesn’t mean that everything is fine all of a sudden.

Elizabeth: Right? I mean, they’re likely to be discharged alive because of hospitalization number one, and number two, this concept of graduation, which is actually conditioned stabilization, right? So it’s that they don’t decline fast enough in order to remain eligible for hospice. It’s not that they’ve gotten better. They’re not going to get better. It’s that they’re not getting worse, kind of a fast enough pace.

Alex: I’ve seen some patients get better clinically, you put them on hospice, you get services arranged to help them. And maybe they start putting on weight and improving in a number of ways and thriving. That’s not common, but that does happen. But, we should get to results. Right? Eric, did you have another question before we got results?

Eric: I just want to go to results. I want to know.

Alex: What’d you find?

Elizabeth: So, we found three things. We found that 40% of patients with dementia had one of these undesirable outcomes of a long length of stay or a live discharge. So that means that for a significant proportion of folks, hospice isn’t working as intended if you have dementia. The second thing that we found was that home hospice patients were at particular risk for live discharge in a long length of stay. And then the third we found was that having a nurse visits at any point, regardless of how long you were in hospice, if you were in hospice for two weeks or six months, if you had a nurse visit in a previous week, then you were more likely to die within six months.

Eric: And that last one kind of makes sense to me, right. Nurse visits. Something’s up. Is that right? Like your experience Lauren as a hospice nurse?

Lauren: Yeah, definitely. Yeah. I mean, you’re watching those patients more carefully. I mean, you should be going to see them more often.

Eric: But 40%?

Elizabeth: 40%,

Eric: Long length of say. What was the live discharge rate?

Elizabeth: So the long length of stay was almost 60% of that. And 40% had a live discharge.

Alex: Live discharged. And that could be for various reasons. They were no longer declining and the hospice disenrolled them, that’d be one.

Elizabeth: Yes. That’s the second reason. The second most frequent reason. Most people who are discharged alive with dementia, go to the hospital. And that’s actually the case for regardless of patient population, about half of life discharges are due to hospitalization.

Eric: I’ve heard there’s a lot of state by state variation on live discharge rates and rehospitalization rates. Is that right? Or am I just making it up?

Elizabeth: It sounds like it could be right. I’m not sure.

Lauren: Yeah. I was just looking at an article by Joan Tino, another article by the illustrious Joan Tino, the other day. Maybe she’s listening to this.

Alex: Hi, Joan. [laughter] How are the dogs?

Lauren: Yeah. She did a study a number of years ago, looking at state level of variation and the rates range from like 10%. Like discharge rates to 40%.

Eric: And is the reason the live discharge rates to hospital is so high because when either people change their minds or they get rehospitalized for something and the hospice disenrolled them because…

Elizabeth: So you can’t be enrolled in hospice and hospitalized. There are some exceptions where hospice have arrangements with hospitals… You guys are clinicians, you know this better than I do… But where hospice have arrangements with hospitals to accept patients on a very short-term basis for symptom management. But what we hear from, and I’m doing a study where I’m interviewing clinicians right now as this clinicians about what goes on with live discharge is that the family members call 911 because there is some sort of change in the patient’s condition. There’s some sort of symptom and hospices available 24/7, but they’re not present 24/7 and physically present. And when something happens in the middle of the night, it might take some time for hospice to respond or to be able to be honest on site and family members call 911.

Alex: I wanted to ask Libby, what did you think of these findings? They surprise you? They kind of what you thought you were going to find?

Elizabeth: I didn’t find them terribly surprising given what we know about other folks who have done this research and other papers that we’ve done in terms of risk factors for live discharge and we found that in dementia… The literature consistently shows that dementia is a risk factor for live discharge in particular. And knowing about the trajectory long length of stay goes hand in hand with that. What I think is interesting is trying to figure out the why, right? What’s going on? Why are home hospice patients more likely to have a live discharge or a long length of stay, and if they are receiving hospice in a nursing home and we could think through that and come up with ideas, that I know of, there haven’t been studies that talk about that.

Eric: Why do you think that? Top two ideas.

Elizabeth: Lauren, you want to go first?

Lauren: Oh yeah. I’ve thought about this a little bit. We found a similar result in the study that we’re working on right now. And I think it’s probably two things. I think it’s, One: that the patients enrolled at home are maybe healthier. So, they might be getting enrolled earlier because there is a way to get services out to those patients where there’s really a vacuum otherwise. So I think that’s part of it. And then the other part of it is that they don’t have services around them, right? If you’re in assisted living or a nursing home, you have a nurse there all the time. And so if something an emergency comes up, then you can access that person. Whereas for the people who are at home, they’re especially vulnerable, because like you said, something happens in the middle of the night, you have to call hospice. Sometimes takes a couple hours for hospice to get out. The hospice might not have educated the patients enough about their options for not calling 911. So that’s my theory about that.

Elizabeth: I think you’re probably right. So we were wondering about that. Even though everybody had meets the same eligibility criteria, maybe home hospice patients are less sick than a little bit. Well, we did not find that in our data. We found a little bit of a variation on an assessment of functional status upon enrollment called the palliative performance scale. But the difference was statistically significant but not clinically meaningful.

Alex: Sorry, are you talking about people with dementia enrolled in hospice at home versus a facility?

Elizabeth: Versus in a nursing home, yeah.

Alex: Versus in a nursing home.

Elizabeth: Yeah. I agree with your hunch, Lauren. We unfortunately couldn’t find it in these particular data, but I think you’re probably right. The other thing too is that I think the family caregiver situation and in home hospice plays a significant role in patient outcomes, whether they have long lengths of stay. In order for somebody to have home hospice with advanced dementia, they either need 24 hour managed long-term care, which is quite generous in New York state that benefits relatively is generous relative to other states, where they need family caregivers who are there to provide in-home care, or who can afford to pay private caregivers to be there. And there may be something about that sort of constellation of resources and support that’s conducive to long length of stay, but also the stress on the other side of that then leads to them saying that “We can’t anymore.” And live discharge.

Eric: So I guess going back to the big picture, like “So what?”. So we have long lengths of stay. Maybe Medicare cares about that, but that seems like, “Hey, that’s great. These people are getting long lengths of stay or their needs aren’t getting met in hospice, so they get hospitalized or they’ve been in hospice for so long that they graduate.” Is that a bad thing?

Lauren: Yeah. So maybe I’ll take a stab at this one. I think when Krista and I were writing this paper, this editorial, we really just wanted to drive home this idea that live discharge is… it’s really bad for patients. Presenting people and they’re asking me these exact questions that you are like, “Oh, maybe, maybe it’s not so bad that they went on hospice. They had hospice for a while and then they got better” and, “Oh, isn’t it great that they got better. And maybe it’s good that they had these services for some period of time and then didn’t.” But based on my clinical experience and Krista has some personal experience with this, that this is a really negative experience for patients.

Eric: Particularly in patients with dementia, right? This is not like a cancer patient who is now in remission. This is people with dementia. Their dementia isn’t gone all of a sudden.

Lauren: Exactly. It’s not like a Hollywood movie where they thought they were going to die of cancer and then they’re miraculously cured. No, it’s a person with advanced dementia. They’re usually bed-bound, they can’t eat and then they’re just, they’re just not necessarily, they’re stable, maybe stable at that level, or even still declining slowly but not fast enough to stay in hospice. So then you have, hospices who’ve spent providing these comprehensive services and providing multiple layers of support for patients and caregivers,

Eric: And durable medical equipment.

Lauren: Yeah. Medical equipment, meds, medications, and hospice comes in and kind of acts like a HMO. So it’s taken over all of the patient’s care. And so when hospice leaves, it’s really a bad experience for patients. And what makes it worse is for people with dementia and their caregivers who are already, this is already research has shown, this is people with dementia end-of -life and the caregivers have a particularly bad time in the last year of life, but there’s no other services out there. They’re just discharged into a vacuum. It’s just they had all these services and now it’s gone. And so we really just wanted to emphasize that this is not a good outcome. Like we should not be…

Eric: I love that we should not be calling it graduation. This editorial is changing cause I called it graduation. After reading this, I feel like I’ve disrespected patients and family members by calling it that even informally, not in front of them. And I loved how you called it. It’s really getting expelled.

Lauren: Yeah. Yeah. So, so yeah. So we really want to just drive this home that, this is fragmenting care for patients. This is creating disruptions in our continuative care. We want seamless, integrated, comprehensive care for people with dementia end-of-life.

Eric: And just a perspective, it also seems like there’s two issues that you found here Libby is, one: you have people who get hospitalized. So, hospice isn’t meeting their needs at that point, because they’re being hospitalized for some reason, maybe it’s where they want to go, maybe it’s just their healthcare needs aren’t being met or the caregiver needs aren’t being met. So, that was one issue. The second issue I feel like Lauren is addressing is these people who have been in hospice for a while, stabilized and get discharged. I guess from your study is, do we have any data on those people who have been around for a long time and then have a live discharge? Not those people who’ve been around for four weeks and get rehospitalized. People who’ve been around for six months and then they don’t get re-certified for three months and then they don’t get recertified.

Lauren: Yeah. So, I’m trying to think. We actually published another paper in 2019 in JAGS that looked at risk factors for live discharge due to conditions stabilization, which is the technical term for expulsion or graduation. And those folks were more likely to have dementia. They were more likely to be members of underrepresented racial and ethnic groups. I haven’t looked at that paper recently and I don’t recall all of the details. I don’t think that there was a difference based on Medicare and Medicaid dual eligibility status. And then they also were… they met eligibility requirements upon enrolling in hospice, but they were higher functioning. Right. And then those who died sooner, or didn’t experience live discharge due to condition stabilization.

Eric: I’m going to give each of you a magic wand. You got magic wand does one thing and only one thing.

Alex: Just the one?

Eric: Just the one.

Alex: That’s going to make it harder.

Eric: Yeah. Here, should I give them two? Should I give them two of these wands?

Alex: No, one’s good.

Eric: All right, one thing. One thing, each of you. If you have a magic wand, you make one change to the hospice benefit to address this issue. What would that change be?

Alex: Your benefits can be additive, so.

Eric: You don’t have to say the same thing unless it’s really important.

Elizabeth: Should I go first?

Lauren: Yeah.

Elizabeth: Cause you’re probably going to have a better one, Lauren. So you can add to mine.

Elizabeth: I think the one change is that we really need to revisit the six month or you’re out rule. I don’t know what the response is, but perhaps it has something to do with looking at actual clinical trajectories for folks and expanding-

Eric: But doesn’t the recertification period actually do that? Like, “You can recertify. Oh yeah.” I still think they have less than six months to live at six months.

Elizabeth: Yeah. And of course there are people that receive hospice. A lot of people receive hospice for more than six months. I mean, a lot of these long length of stay folks weren’t necessarily discharged alive. They actually died in hospice but the problem is, is that the way that it’s set up is that hospices with large numbers of patients with long lengths of stay on their roles are then subjects to audits, right? Yeah. Inspector general. And there’s research on that. So it becomes this sort of it makes things tough. I think.

Eric: Yeah.

Eric: Lauren, magic wand.

Lauren: Yeah. Okay. So, so I decided I’m going to hedge this question.

Eric: Let’s hear the hedge.

Lauren: Cause I really go back and forth about this. I think about, do we want to try to change the hospice benefits and try to adapt it, to make it more suitable for people with dementia and non-cancer diagnoses? Like, for example, getting rid of the six month prognosis or changing the payment structure. However, but then, I also think that another approach would be to try to develop another benefit, a long-term care benefit that which is similar to hospice, it provides the same level of comprehensive supports in the home, but doesn’t necessarily have to be for at the end-of-life. And then you really keep hospice for those last weeks and months of life. And I go back and forth on this because there’s so many great things about hospice and it’s been around for a long time and it’s really well established. People know what it is. It’s already scaled, but then it’s not working and meeting the needs for people. And also there’s all the people who aren’t necessarily ready for hospice. So, I don’t know. Maybe someday I’ll come back on the show and I’ll give you a…

Alex: You don’t have the answer. You have the magic wand.

Lauren: Maybe Alex will remember the next time I’m back unlike before.

Alex: I feel so terrible.

Alex: Is there anything else that we didn’t talk about that you want to talk about? Either about the study or something you said in your editorial or other thoughts that have come up today?

Elizabeth: No, I mean, I think I just want to definitely give a shout out to my close collaborator, David Russell and everyone else who helped on this study and the other studies that we published in conjunction with this grant. It was wonderful to have such a great team to work with and so much depth and knowledge to drawn. So, thank you.

Lauren: Yeah. It’s been great to follow your work. I’ve been following all the papers that have been coming out of your group. Yeah. I’ll thank Krista Harrison who’s my partner in crime here, and it’s a great to work with her on these projects as well.

Alex: She sounds familiar. Maybe she’s been on GeriPal. [laughter]

Eric: I want to thank both of you for joining us but before we end. You got a little bit more Landslide for us, Alex?

Alex: Well, I’ve been afraid of changing . Cause I’ve built my life around you . But time makes you bolder . Even children get older . And I’m getting older too. I’m getting older too. I took my love, I took it down.

Eric: Again, very big thank you Libby and Lauren for joining us today, it’s been a great experience. Learned a lot.

Alex: Terrific topics.

Eric: Yeah.

Elizabeth: Thanks for having me.

Lauren: Thank you so much.

Eric: Big thank you Archstone Foundation for continued support and all of our listeners for continued support. If you have a second, please rate us on your favorite podcasting app. And with that, goodnight everybody.

Alex: Goodnight everybody.