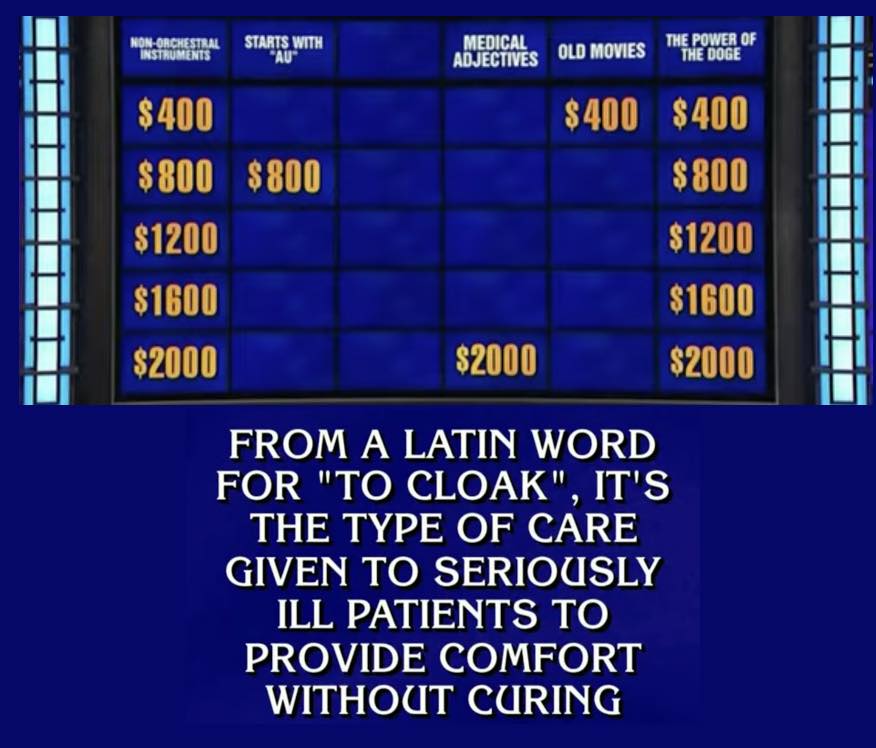

Earlier this year palliative care was the correct response to the following clue on the game show Jeopardy:

From a Latin word for “to cloak”, it’s the type of care given to seriously ill patients to provide comfort without curing

What struck me most was not that palliative care was a question, nor that it made it seem that palliative care isn’t provided alongside care directed at curing, nor was it that hospice was the first buzzed in response, but it was that palliative care was the $2000 question in the Double Jeopardy round! The fact that palliative care was the hardest of questions told me that we have a massive messaging problem in our field.

So what do we do about it? Well, on today’s podcast we talk with Marian Grant and Tony Back, who with support form the John A Hartford Foundation and the Cambia Health Foundation, have done a deep dive into the research on layperson perceptions of palliative care, hospice, and advance care planning. The result is a new toolkit to help us fix our messaging & engage the public: seriousillnessmessaging.org

Questions we talk about include:

- What do we know about the public’s perception of palliative care, hospice, and advance care planning?

- What’s wrong with the “pictures of hands clasping each other” as our palliative care meme?

- How can we bring in marketing strategies into our public messaging?

- Don’t palliative care clinicians already know how to explain things with empathy? Why is this different from clinical communication skills?

- If we avoid talking about death, is it just contributing to the public death denial that is rampant in American culture?

Related links

Public Perceptions of Advance Care Planning, Palliative Care, and Hospice: A Scoping Review

https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/full/10.1089/jpm.2020.0111

Public Messaging for Serious Illness Care in the Age of Coronavirus Disease: Cutting through Misconceptions, Mixed Feelings, and Distrust

https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/full/10.1089/jpm.2020.0719

Effective Messaging Strategies: A Review of the Evidence. Communicating to Advance the Public’s Health: Workshop Summary

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK338333/

Eric: Welcome to the GeriPal podcast. This is Eric Widera.

Alex: This is Alex Smith.

Eric: And Alex, who do we have with us today?

Alex: We are so fortunate to welcome back to the GeriPal Podcast Tony Back, who is a professor of medicine and palliative care physician at the University of Washington, and co-founder of VitalTalk. Welcome back to GeriPal, Tony.

Tony: Hey, thank you.

Alex: And we’re so delighted to welcome to the GeriPal Podcast Marian Grant, who is a palliative care nurse practitioner and marketing consultant, and she is at the University of Maryland Medical Center in Baltimore. Welcome to the GeriPal Podcast, Marian.

Marian: Thank you. Great to be here.

Eric: On today’s podcast, we’re going to be talking about evidence-based messaging for serious illness care. This is going to be a lot about talking to the public about three things: advanced care planning, palliative care, and hospice. But before we jump into that topic, I think somebody has a song request for Alex.

Marian: I do. We would very much like to hear him do I” Heard It Through the Grapevine.”

Eric: I’m assuming I know why you chose Heard It Through the Grapevine, but can you tell us why?

Marian: Well, we’re going to talk about this amazing new online toolkit that we’re launching and we thought we need to find a grapevine to tell people, and we thought of you guys.

Alex: Ah, okay. That’s not where I thought you were going to go. I thought you were going to go with… I heard about palliative care through the grapevine and this is what I heard, and it may be totally wrong.

I wish I had heard it directly from you because that might have been a different message. So there are a lot of ways that this song could work. All right. I like it. Here’s a little bit.

(singing)

That’s a fun one.

Marian: Yay.

Tony: Beautiful.

Eric: First, thank you for both coming here. We’re going to be talking about, in some ways, marketing hospice, palliative care, and advanced care planning. How did you both get interested in this? I’m going to turn to Marian first.

Marian: I have been a palliative care nurse practitioner for a number of years. But before I became a nurse I had a long career at Procter & Gamble in brand management and I worked on the Covergirl and Max Factor business. It was my experience as a hospice volunteer that maybe leave the corporate world and go to nursing school and ultimately become a palliative care nurse practitioner. From the beginning of coming to palliative care, I’ve noticed we’ve had a messaging opportunity, perhaps a problem.

Eric: I liked how you start off with opportunity that seemed very…

Marian: Doesn’t that seem very marketing oriented? Yes.

Eric: Yes.

Marian: I knocked on a lot of doors and offered my help as a former market brand person. It was only this project and Tony where we were finally able to let me contribute in this way.

Eric: And Tony, you got like five million things on your plate. Why this?

Tony: Well, what happened was several years ago I did a think tank project on the future of palliative care with a bunch of stakeholders, people in and out of the field. We did this big scenario planning about what’s the future of palliative care going to be? What would it look like? And what are the factors that would really be the big influences on what happens?

The two factors that we came up with that would really influence and change the future are one was the existence of the payment model and two was public engagement and public acceptance. There were other people working on the payment model, and so we decided in the next project to work on public engagement and public acceptance.

I had had a phone call with Don Burwick at the time, who was in his car and on his way to work and the first thing to me he said was, “You guys have kind of an image problem. You have a messaging problem. I love what you guys do, and it’s not working.” I thought, “Hmm. That’s kind of an interesting confirmation.” So that’s how I got into this world of public messaging. I was also interested in it because I’ve seen and participated in so much direct-to-the-public communication from people in the field that is heartfelt, beautiful, based on vast experience. It’s all been about the really hardest parts of dying. I feel like in my own development as a palliative care person, I’ve kind of come through a certain arc of that and then to see now where we’ve been doing in this project, interviewing of regular people who aren’t necessarily the patients, like their views, honestly, it was an eye peeling, humbling, horrifying experience.

Eric: Can you give us some examples of what are the eye opening or horrifying things that you found out?

Tony: Oh, yeah. First, nobody knows what we’re talking about. We did all these focus groups worldwide from every part of the country and we were talking about advanced care planning at the end of this. We were talking over the interview and the moderator goes, “You know, nobody used the term advanced care planning.” And he was right. Not one single person actually knew what advanced care planning was, used that term, had it right. I was like, “Hmm, that’s kind of an issue, isn’t it? Since we constantly are talking to lay people, the general public about advanced care planning.”

Eric: Well, I think it’s also fascinating because we’ve done how many podcasts on advanced care planning last year, Alex?

Alex: Yeah. We’ve done like eight because there’s a little controversy. You may have heard…[laughter]

Tony: I know. So I get that that’s a whole other layer of it. Like, what should we even be doing there? But the fact is that when you talk to the general public about what we think we’ve been doing, they’re like, “What?” So that was one was of the examples that was kind of interesting.

The other really eye peeling example for me was the deep, deep distrust of the medical system that came out in every conversation. The anecdote I really remember was this woman talking about her experience at an ICU. We had tried to actually select people who didn’t have a serious illness. She did not have a serious illness at the time. She was talking about a past experience. She remembered this time when something happened and all of a sudden all these doctors descended on her and her husband said, “Wait a minute. No, no.” He said, “My wife is not going to be a cash cow.”

The assumption for most of these focus group members was that medicine is a business, that there are incentives that physicians and other clinicians are responding to that are not transparent, and that decisions are being made that are in the interests of the health system, not in the interest of the patient and family. And nobody wants to talk about it. I know it’s a little bit of a conspiracy theory thing, but whoa, the mistrust and distrust, it was really humbling. That really made me concerned about this.

Marian: But some of the eye peeling things we were kind of anticipating, which is when we told the public, these people in the focus groups, about things like palliative care in an optimal way, they said, “Wow, what is that? I like that. That sounds really good.” And then they said …

Tony: This sounds too good to be true.

Marian: Really, we were just discussing what it is we normally do. But…

Tony: Garden variety.

Marian: … then they said, “Wait a minute. I’m confused. I thought that was for end of life.” I mean, it confirmed all the work that CapC has done and work that other people have done, which is that people that they do know about palliative care, which is not many people do, they think it’s for end of life. It just reiterated that if you did messaging better, if you actually use the right concepts and the right terms, people thought, “I’m going to ask about this.” By the end of the focus groups people were willing to do advanced care planning. We had talked them into that. But also they walked out saying, “I need to ask about this because I know people who would benefit from this.” That just confirmed that if we could help the field do more of that and less of some of the things that are not helping, more patients would ask for these services.

Eric: You have this new website, just came out, seriousillnessmessaging.org. Why even do this? Because you bring up CapC. They did focus groups. I can’t even remember. It has to be over a decade ago now…

Tony: Big national survey. Yeah. What their big national survey showed is no progress whatsoever in public awareness of what palliative care is. So, let me be super clear. What we have been doing for the past decade has not been working in terms of reaching new audiences in the public. Even with this whole discussion about diversity, even in our regular community, we are not actually making progress when you look at nationally weighted surveys. So that’s the other part. That’s the other piece of data on top of our focus group anecdotes.

Then there was that New England Journal catalyst study that showed that the healthcare executives thought that 60% of the people in their hospitals who could benefit from palliative care weren’t getting it. So, it’s kind of on top of that. So that’s the thing.

What we’re trying to do with this toolkit is give clinicians, all of the people who listen to this podcast, who do talk to the public in different ways, to make them aware that that is a different thing than talking to a patient that they’re taking care of or family who they’re working with, and that when they talk to the public, they could take advantage of all this empirical research that we’ve dug up that actually shows what regular people are ready to listen to. Because Marian, you can probably talk about the marketing principle here, because we’re constantly telling people what we think they should know. But what do the marketers do?

Eric: Well, hold on before we give the marketing principles, because I really want to dive into that. Tony, I’m going to push you. I’ve done VitalTalk training, I teach VitalTalk to all of our fellows. Most fellowships give their fellows communication training. We are experts at communication. Why focus on this? We should know how to talk about palliative care. We’re experts.

Tony: Well, yes. We know how to communicate with patients, but communicating with the public is a different beast. Marian, how would you put that?

Marian: Well, yeah. When you are talking with a patient, you are already in a medical context. They are a patient. They have a serious illness. You’ve been introduced, hopefully. So they’re already set up for that. But if somebody is looking at a brochure in the waiting room of the ICU or they’re somewhere online and they’re getting social media and they hear about palliative care, you have to help them understand what’s in it for them, and leading with a better death is really not the way to do it.

Tony: But the thing I will just say, the parallel there is think of the big public health campaigns that have been really successful: drunk driving, smoking cessation. Look at the way they talk to the public, referral like HIV prep. Look at the way they talk to the public. It’s very different than the way that clinicians talk to patients inside. That’s because you’re getting people out of context. You’re getting them with a little teeny slice of their information and you’re just trying to build some willingness for them to hear more. But go ahead with your thing there. Yeah.

Eric: Yeah. Well, let’s talk about that then because how is it different? You mentioned not leading with good death.

Tony: Yeah.

Marian: Right. Yeah. Because I hate to break it to this audience, but most Americans are not interested in dying at all. To many of them, a good death just sounds like a crazy notion. Well, how could a death ever be good? I often look at what our pharmaceutical competitors are doing in their advertising, and we are not suggesting you go to those extremes. But people who are taking those medications are looking good. They are having fun. They are living positive lives. Those are very effective marketing things. I worked on the Covergirl business. We used supermodels, right? Because if you want to get people’s attention and you want them to be interested in what you’re talking about, you have to paint a positive picture. Now, I think what we’re advocating for on this toolkit is not to be unrealistic, but showing frail, older people and hands is not going to stop anyone and have them say, “My God, what is that? I think I need that for my mother.” No. You have…

Eric: So, you’re saying that the palliative care and hospice meme of having two hands clasped together showing…

Marian: It’s terrible. It’s terrible.

Tony: It’s over, you guys. Yeah.

Eric: Wait. Why is it so terrible?

Marian: It is not appealing. It is not distinctive. You have cancer centers offering them cures and you are offering them frail hands? You need to show them how palliative care could help them live better. And frail hands does not do it. Yet, because we have done that so consistently, we have persuaded the media when they do stories about us, they use frail hands. Medicare, on their brochures, frail hands. If we do nothing, we have to stop that.

Tony: And what it signifies is you’re dying. If you look at public opinion polls about what Americans are interested in hearing about, it’s about 10% of them that are interested in dying. I’m a longtime Zen practitioner. I’ve been thinking about this for a while, and actually I’m a weirdo. It is not normal to be thinking about dying in American culture, and it’s not aspirational. In our culture, the way it is given to us now, looking forward to your death and what happens, that is not a highly prized experience. I mean.

Alex: I wonder if I could push back on this point a little bit and that if we bombarded the public with images of, let’s say in geriatrics, that aging is older adults playing volleyball on the beach, and if we bombard the public with images of palliative care as being younger patients with cancer, ballet dancing, which I know has been a marketing…

Tony: Yeah, I know.

Alex: Then we are exacerbating this issue that already exists in our society, that aging is to be avoided, that being frail is undesirable and should be out of sight, that dying and the loss of muscle mass, loss of function associated with dying is something that should not be in the public sphere. That’s sort of playing into this and exacerbating what is already a strong theme in American culture and marketing, rather than confronting and putting forward positive images of, say, happy older adults in wheelchairs with disability, or people who have end-stage cancer who are smiling and with their family though they may have profound muscle wasting, be emaciated in bed. So that rather than trying to sweep some of these images of disability and frailty and the challenges of the impact of serious illness, we should instead be reimagining them as positive. Just try push back here a little bit and see what your thoughts are.

Marian: Lovely thought. Not what the public is interested in. So what is your objective? Are you going to try to re… And you talk about bombarding them with messages. We will never have the money to bombard them with messages. We have such a small footprint in terms of advertising.

So, I think what we have seen in this project and what we have looked at from the evidence is when we go with our best foot forward, when we tell positive stories and use positive images, and we’re not talking about supermodels, we’re talking about no old hands, people start to think, “Oh, what is this?” Because most people don’t know what it is. If you can get into their attention with something that sounds like something they would want an extra layer of support, team-based care for them and their family. These are ideas that CapC has tested multiple times that we know are strong. So we’re just saying to the field, let’s use the evidence we have, and let’s speak purposeful about this and not grab the standard hand shot and do things a little bit differently because what we’re doing right now has not changed anything. We have a problem in the field that we’re considered the acute death team at the hospital. Well-

… talking about a good death is not going to fix that.

Tony: Yeah. I would also say that, and I know there is a long honorable strain of thought that is from hospice, that we need to embrace death as part of life and we need to be a little bit confrontational with this. If you look at what’s happened over the past 20 years, it hasn’t really worked. I guess I point to a different kind of meme about aging, which I think has been very successful and very interesting in a different way, which is women who don’t color their hair. They’re beautiful, accomplished woman and they have gray hair. Actually, I think during the pandemic, we’ve actually seen that change. Beautiful accomplished, experienced, successful women, they have gray hair sometimes. Actually, we’ve kind of detoxified this whole… I would say we are in the process of detoxifying it. I wouldn’t say we’re done because there’s that Canadian anchor who just got fired.

But I do think it’s this thing where that is changing and I actually wonder if what we need to do is a little bit more on the edge of incremental change because if you talk to the experienced marketers, they say go to what the public likes and approve of first, then build on that. What we’ve been trying is let’s change their views to our way, and the honest answer is we’ve been struggling. I get you guys live in San Francisco. There’s the Reimagine Conference and all this sort of stuff.

Eric: Reimagining death, right?

Tony: Those are edge-of-the-culture pushing things. EndWell is an edge-of-the-culture pushing thing and I think those are really valuable. I’m not saying those should stop. I am just saying that we need to create a way of looking at what happens in serious illness care as people living well. So the images that you were talking about, Alex, people having a good time with their family, people who are with people who are obviously connected to people they love. You’ll see there’s a whole image gallery in our toolkit that has images like that that you can use in place of the hands like this. The hands like this. Right?

Eric: So Marian, I got a question for you. When you think about this and this toolkit, are there some really basic marketing ideas or tips that you have when we think about messaging, advance care planning, hospice or palliative care. In that, again this is GeriPal Podcast, geriatrics falls into the same boat. There are 86-year-olds living in a nursing home with frailty, who I say, “I’m a geriatrician.” “Oh, yeah. That’s great. I could use that one day in the future.” Okay. Like, we have a messaging problem. Are there tips from a marketing standpoint?

Marian: Well, there are. I guess we should also step back and say that this project has been funded as a grant by the John A. Hartford Foundation and the Cambia Health Foundation. We had wonderful resources to do this.

One of the things that we started with was the recognition that although we had better messaging for all these three components, advanced care planning and palliative care, and hospice, different organizations had different needs and we couldn’t come up with phrases that everybody was going to be able to use. So, we came up instead with messaging principles.

The first principle is kind of marketing 101, which is you lead with the benefits. You lead talking about whatever it is you’re offering, with what is in it for your target audience. We know that for palliative care, because of the work that CapC has done, that the idea that it’s team-based, that it is appropriate in any age and stage of an illness, all of those are the benefits for palliative care.

The other thing that we know is very compelling is using stories. But our field has historically used horror stories, and we’re saying you need to use stories but you need to use stories where it ends well, which doesn’t mean that the person lives forever. It just means that it’s telling people about horrible, serious illness experiences or horrible deaths isn’t motivating to the public. They’re like it, “I don’t want to know that.” But if you tell somebody about a situation where somebody got help in the hospital or in the community with palliative care, and it helped them on all these levels, then we have such stories on the toolkit. When we told them, that’s when people said, “Man, this isn’t what I thought palliative care was.” Bingo.

Eric: Yeah.

Tony: So remember, Art Field has started with don’t end up doing this; don’t do this; don’t do that; don’t have a bad death. There was a lot of well-meaning bioethics that really got that started, this whole thing about futility. We have assumed that that would be good public messaging. I think what we’re saying is that there is a lot of evidence to show that is not good public messaging. It’s still good bioethics. It’s just not good public messaging.

Eric: Well, I think it’s also interesting because it’s probably a feedback I give not infrequently in the hospital because, for example, hospice, I see a fair amount of residents and fellows talk about hospice, and they’ll start off with all the things that hospice won’t do. “We’re not going to do this.” You change the code status.

Marian: Who’s going to sign up? Right?

Eric: Yeah, it sounds terrible. Those are the things that you think about first. We did a podcast on nudging. I think I mentioned that podcast, Every single podcast. But it like nudges people not to want it. It’s a strong motivating nudge. If you talk about the things that it won’t do, it pushes people to not choose it.

Tony: Totally.

Marian: Because they have other choices. I don’t think we realize that. As a marketing person, you have to not only be aware of what you’re saying in your messaging, you have to be aware of what is going on around you. What do people with serious illness hear? Who do they hear from? Well, they hear from the pharmaceutical business. So we know what that’s all about. They hear from hospitals, I see advertisement for the hospitals where I’ve worked and I’m like, “Oh, my god, really?” They hear from…

Tony: Come to us for the miracle cure.

Marian: They hear from cancer centers.

Alex: Yeah. Cancer Centers of America.

Marian: Right? That is the competitive messaging space that people with serious illness are actually living in. Not to mention the fact that they and their families don’t want to die and want to do everything they can. Then we have to be part of that. We have to recognize we don’t have a lot of money, and if we get their attention at all, we have to sound like we are a valid choice versus CyberKnife technology. So, I think we have wonderful things to talk about, and none of the things in the toolkit are untrue.

The best marketing tells the truth, but in a way that people find appealing and refreshing.

Tony: Compelling.

Marian: You know when they get palliative care, they’re going to be happy. They’re going to be sorry they didn’t get it sooner. Just like when they get hospice, they’re sorry they didn’t get it sooner. We’re just talking about getting your foot in the door to get them to at least reach out and ask for information about these things.

Tony: I do think the example you bring up, Eric, which is how a resident introduces hospice, is where the messaging and the communication kind of overlap a little. I do want to say that we are talking in this toolkit about how do you get the public’s attention and get them to a point where they would ask for more. Like, when a resident is talking to somebody about hospice in a clinical situation, they need to introduce it and explain it as a valid option and talk about that in the context of the choices the patient is facing and the clinical situation the patient is facing. I will say that conversation rapidly goes into a different place, which I would say that’s patient-clinician communication. But the thing about leading with benefits, it’s the exact same psychology.

Eric: Also, since we’re talking about cancer centers, too, we did a post. There was an article that came out about cancer center advertising. God, that was a while ago. We’ll include it in the show notes. But the vast majority of advertising included emotional appeals and that is…

… evoking hope. This is your hope. Or battle language, like, continue to be a fighter. Are you a fighter? Or like, fighters welcome. Fighters, welcome was one of those from Cancer Centers of America.

Tony: Totally.

Marian: … and we offer hope as well, but what we want to try to get the field to talk about is the hope is living well with a serious illness. The hope is having help for you and your family and support and not being physically uncomfortable. Those are valid hopes.

Tony: Yeah.

Eric: Yeah. And also…in the cancer centers, it was patient testimonials. It was never…patient testimonial is, “Oh…this bad thing happened.” It was, “Look how amazing things turned out.”

Tony: Totally. Now, I think there’s a way we can do this messaging without falling into the hype machine. I do think the cancer centers are in this hype machine and they have learned over time that they get volume and donations from those emotional appeals. That’s why they just continue. It’s not just Cancer Centers of America. My cancer center does that kind of stuff. Academic cancer centers all over the country, they do a version of the same thing. So it’s all over, and it’s for different kinds of motivations, honestly.

Marian: But the idea of an emotional appeal is also a marketing principle.

Tony: Totally.

Marian: Because what we’re learning in behavioral economics is we don’t make pretty much any decision without there being an emotional component. We certainly don’t buy appliances without there being emotion involved. When you come to serious illness, very much emotion involved. So, we’re talking about you can have messaging that is very negative in terms of emotions, between the visuals, between the concepts that you’re talking about. People are not drawn to that. You can have messaging that’s positive emotionally, that sounds like or paints a picture of an appealing yet realistic future that people are drawn to. Again, it’s the supermodel thing. Women were more predisposed to buy things that made them think, “Wow, I could look better. If I wore that lipstick, I could look better. My life could be better.” It’s not realistic but it’s emotional. But good marketing recognizes that.

Alex: Mm-hmm. I wonder if I could just put you on the spot here and say, okay, let’s pretend you’re one of our GeriPal listeners. In your idealized world, they’re getting a phone call from a friend who’s like, there’s some situation. They have cancer, and you want to recommend palliative care, or maybe it’s… Concoct for us the situation in which you would ideally have our listeners use this language that you’re proposing. And then what would you say? What words do you want them to say, if you could channel that language?

Tony: Well, I’m going to give you a slightly different example, use this case, because that use case a friend calls you about a friend, that’s like a curbside consultation to me, right? They’re going to tell-

Alex: Yeah. Fair.

Tony: … you some… I think the use case that I would like your listeners to consider is a journalist calls you. They say, “I’m writing a story about what’s the difference between hospice and palliative care.” What you would say is, “Let me tell you about this patient who really benefited from palliative care. She was a blah, blah, blah. She was a grandmother. She loved to crochet. She has five grandchildren. She always wanted to be with them, and her current passion is to try and help them go to college. She got a horrible cancer. All during the cancer, she also saw a palliative care team. The palliative care team helped her deal with her pain, helped her make good choices about her cancer treatments. She got to go to all of her grandson’s baseball games, and she got to make every grandchild something special for them when things were getting really serious. That’s what she loved about palliative care. And she said to the team, ‘God, I didn’t realize I could do all this even while I had cancer.'”

That is what I tell the journalist. The journalist say, “What about hospice?” I’d say, “Hospice is a different thing. Palliative care and hospice are two different products, and we have to stop talking about them in the same breath.” So I would say, “Palliative care is this. Hospice is…” But I would tell a story first, and say this is what palliative care is. This is what your readers need to know about what palliative care can do for you.

Alex: Marian, anything you’d add to that?

Marian: Yeah. I’ll give you another example. My hospital, we finally have enough of a team that we want to do some marketing. One of the nurse practitioners contacted me the other day and said, “Take a look at these logos for our brochure,” because we’re going to do a brochure that’s going to be posted online and it’s going to be in the hospital. Hands. Hands. And I said, “Okay. No.” CapC actually has text for a public brochure that you can find outside of their paywall on their marketing section of their website. But I said, “We should use a much more appealing image and we should use these phrases to talk about palliative care.” Maybe you’ve been asked to speak to a community group; maybe you’ve been asked to speak to your church or some faith community about what you do. You don’t lead with death and dying stories. You open with a story like Tony talked about, and you use some of the CapC phrases and you use that to make people think, “Wow, I have not heard about…” Because 75% of people don’t know what palliative care is.

Tony: They don’t know what it is. Right.

Eric: Mm-hmm.

Tony: Yeah. Yeah. For example, imagine you are a family member who is looking through a hospital website, my hospital’s website, and you stumble onto palliative care. They have some kind of horrible illness. You look at the list of services, which is alphabetical in my case. And the first service is bereavement.

Alex: Oh no [laughter]

Tony: Hello.

Eric: And there’s a probably clasping of hands right next to it.

Tony: I’m not even going… I’m not even…

Eric: Well, I want to highlight… So your website, which is fabulous. I’m looking at the palliative care section. You scroll down. It gives you what you typically do and what you should do instead, giving you words that you can do that. You scroll down more, there’s a steal my message section where it’s short bite-sized chunks, like an extra layer of support; you can have quality of life while getting treatment for serious illness. You can steal that. Right next to it is a picture that is two people smiling. It kind of argues against Alex’s earlier thought that are we just showing a frail, older adult now water skiing in Lake Tahoe.

Alex: Yeah. Right. Supermodel. Yeah.

Eric: But one of them is, it looks like a caregiver and a patient both smiling, looking at pictures. It’s not like a supermodel with…

Marian: Right. This isn’t Beyonce. They’re normal. One of the things that we heard from… This project, last three years, we’ve worked with the leading organizations in the field, the palliative care groups, hospice groups, advanced care planning. They’re 13, 15 groups we’ve worked with. And they have changed. They’ve started to change their messaging. One of the things that they said to us though, was… So there were five messaging principles. You can see them on the toolkit. They said, “Okay. I get it conceptually, but I am not a marketing person. I don’t have money to hire a marketing person. How do I actually have messaging that I can use?” So, as part of this project, we paid a professional copywriter to write copy for us. We went into stock photos and chose what things that we thought were totally appropriate but appealing. We bought them so that the field can use the words in those headlines, and they can use those images for free on this website if they’re going to put a brochure together.

Tony: Right. If you don’t know the marketing or you don’t have time to do it, you can go to these and just steal these phrases.

Alex: I love that.

Tony: We’re trying to populate the field. To be honest, and there might be this thing where, oh, god, we need our own unique thing. But if you think about really good public messaging, they actually repeat the same thing over and over and over and over. The smoking campaigns, the drunk driving campaigns, that the repetition of this as a field actually helps people recognize and remember it because they’re hearing it second, third, fourth hand. So the repetition is okay.

Alex: I wonder if there’s a… Are you seeing that our field is not altogether on this? As you say, there are people within palliative care who very much believe that we should be confrontational about the death-denying aspects of our culture, and that we need to come to terms with the fact that we will all eventually die.

Tony, you said you’re a practicing Zen Buddhist. You think about death, think about suffering. These are things that you think about, and though you’re an outlier… When we talked about this, but I just kind of want to come back to it and say that if the ideas is that we have consistent messaging, how can we do that, if as a field, there’s tremendous disagreement on what the message should be?

Marian: Well, I think we have to be, look, we are evidence-based professionals. I think we have to look at the evidence. The evidence suggests that it is a very small part of the population that is going to be persuadable on just focusing on death. So, you can decide that you want to be Donkey Hodee and spend the rest of your palliative care career trying to change that. Or you can figure out a more effective way to get the services to real people and have them begin to start saying to their friends, “You’ve never heard of this palliative care thing. But I got to tell you, we had it for my father-in-law and it was amazing,” because that’s what really has to happen, is not we talking to the public, but the public starting to actually have direct experience and talk to each other.

Tony: Yeah. Alex, I totally am with you on the need to change the culture. I’m all about culture change. I totally understand that there is a kind of dialogue in our culture that needs to happen about what it means to really get older, get sicker, face your death. There are places in our culture where that dialogue is happening in a really valuable and vivid way. There are movies; there are novels; there are memoirs that come out. I don’t want to do anything to discourage that. I don’t think this does discourage that. I am not saying that we should not have people write their memoirs and not write these accounts that help all of us understand the inner experience of these people.

I am just saying that if you look in the marketplace of images and the marketplace of messages at where regular people are getting information about the healthcare that they choose, that we could be more competitive in getting the public to start to choose us. We are kind of at a point in the field where if we don’t have the public asking for us, the people who control resources are going, “You guys are pretty good. We don’t see the next growth spurt here.” I think the question is, we have to be clear that what are we doing here? This is about changing part of the culture. What you’re talking about, I would say, is changing a different part of the culture. That’s a different dialogue of people who are ready to dive into that. And God bless them. I would not be here without them. I’m saying that is not the way to reach Joe Q public who has a mom with cancer who’s looking at a website about their hospital.

Marian: And that is not the way to talk with journalists. We’ve had a lot of news coverage during the pandemic about palliative care, but much of it is focused on death. I’m a palliative care doc, and here’s how I helped a COVID patient die better. Okay. But again, if we had had stories during the pandemic of how people… Because many people got better from COVID, in part because they had palliative care. I have a really good friend who had palliative care and she had lymphoma, and that was 15 years ago and now she’s cured. Those are the kinds of stories we should be also prepared to tell because if you’re sitting and reading the New York Times and you read a story about palliative care that talks again about just dying as opposed to how somebody might get actually better, might get cured with palliative care, it just reinforces the misconceptions.

There was a study done a few years ago that we have in our scoping review where they asked the public, “Do you know what palliative care is?” And 24, 25% said they did. Most of them thought it was end-of-life care. Well, that’s incorrect. We’re just perpetuating those misconceptions, which come back to haunt us when we are in the hospital and we say to our colleagues, “Could I see this person?” And they’re like, “No, we’re not there yet.”

Tony: Right.

Marian: Right?

Tony: I mean, those journalists are getting background from all the people who are listening to this podcast. They’re journalists who’ve talked to you on background and said, “What is this stuff? What are you guys doing? What is palliative care really?” That’s where we really have to be careful-

… because we can actually influence how they see the field in a totally different way. There’s some things that we can’t control about the press. There’s a lot we can’t control about the press, but because we can’t control what they do and we know what they’re going to do, we’ve got to get our point of view out there.

Eric: Well, I want to bring up one more thing. We’re running up at the end of the hour. But there is a section on your website. The website again is…

Tony: Seriousillnessmessaging.org.

Eric: Seriousillnessmessaging.com. There’s a section on inclusivity. Now, when I think about palliative care, hospice, especially hospice and advanced care planning, there’s a lot of messaging out there about communities. Black patients use advanced directives, advanced care planning, hospice less than white patients, a lot of things that are deficient as far as use. We just need to get these populations.

Tony: I know.

Tell me your thoughts on that messaging.

Yeah. Well, that whole deficiency message is you don’t do enough of this. I don’t think so. I think we need to have messaging that comes from people in those communities that says, “I did this and it helped me live better. I did this and it helped my mom.” I think the age of me as a big medical expert coming to talk to these other diverse communities, that is over. We are going to have to learn to do something different. So, we’ve laid out some principles here in the toolkit. But thank you for noticing.

Marian: The toolkit has a way to contact us. We’re going to put it out there. We want to hear from the field, and we are happy to have these conversations and answer questions and provide more resources because we think we’re on the right track, but we are not going to go anywhere unless we as a group can go there together.

Alex: Can we do a lightning round to wrap it up?

Eric: I just want to say one thing too. I’m going to plug in. We did a great podcast on structural, institutional, and interpersonal racism, about what? Like, six months ago. I just love this because there’s so much focus on distrust. But I forgot which of the folks said this, but trustworthiness is really challenging where the onus of change was. It really was that as healthcare providers, we have to demonstrate our trustworthiness and to demonstrate that we can communicate in effective ways rather than focusing on distrust. I think that’s-

Tony: Totally.

Eric: … a lot of what we’re hearing here.

Marian: Part of that is hearing what people are telling us, which is, “I don’t want to talk about that. I want to talk about living better.”

Tony: Yeah.

Eric: All right. Lightning round, Alex.

Alex: All right. Lightning round. This is a podcast. People are listening to a podcast. We’re social media savvy. Why can’t we just tweet about this? Is there danger in using social media?

Tony: Oh, tweet? Twitter is for professional audiences. Regular people, they’re not on Twitter. Go where the people are if you want to reach them.

Marian: Facebook.

Alex: The pushback is journalists are on Twitter. Paul Span said that every journalist at the New York Times is on Twitter. I know New York Times said we’re on Twitter too much. Get off of it. But still there is an argument for using social media. No?

Marian: There is.

Tony: If you’re trying to reach journalists, use Twitter.

Marian: Right. Right. But if you’re trying to…

Tony: If you’re trying to reach the general public, not so much.

Alex: Not so much. Yeah. Then we talked about how to phrase palliative of care quite a bit, talked about hospice a little bit. How about advanced care planning? What is the pitch to the journalist who says, “What is advanced care planning?”

Tony: Advanced care planning is about you can have a say in your care. Honestly, the title, I would say, needs a little rebranding. That’s a whole other project.

Marian: Yeah. Don’t call it end-of-life planning either.

Tony: And don’t call it a living will because wills are about dying. So really, the pitch about advanced care planning is this is how you can make sure that your medical team and your doctors know what you really care about, what matters. I actually think the pitch about advanced care planning ought to be about what matters, what do you really care about, what do you want your doctors to know. It starts now. It starts with your care now and then it extends.

Eric: Okay. My lightning question is, you have a magic wand. You get any of our listeners to do one thing around messaging. What is that thing?

Marian: Stop with the hands.

Eric: No more hands? [laughter]

Marian: They don’t work. They don’t work.

Eric: Tony?

Tony: Go from a good death to we can help you live well.

Eric: Wonderful.

Tony: Even in the face of a serious illness.

Eric: Yeah. I am going to remember that because hopefully our listeners will remember and hear it from the grapevine that they should be… I got to bring in that song somehow.

Alex: There you go. There you go. That’s good.

Eric: Alex, do you want to end with a little bit? And again, to all of our listeners, please, we’ll have links to everything we talked about on our show notes. But do check out that website. Tony, the website is…

Tony: Seriousillnessmessaging.org.

Eric: And it’s live now.

Tony: … actually use .com, too. We bought them both, and they both direct to the same place. But we’re org type people, .org type people.

Alex: (singing)

Tony: Thank you, Alex.

Marian: Great.

Eric: Thank you everybody. That was a wonderful podcast. Tony, Marian, thank you very much for joining us.

Tony: Thank you.

Eric: As always, thank you to all of our listeners for supporting the GeriPal Podcast.