On this weeks podcast we talk to Julie Bynum on the question “Do Nurses Die Differently?” based on her recent publication in JAGS titled “Serious Illness and End-of-Life Treatments for Nurses Compared with the General Population.” Julie is a Professor of Geriatric and Palliative Medicine at the University of Michigan, and Geriatric Center Research Scientist at the Institute of Gerontology, as well as a deputy editor at the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society.

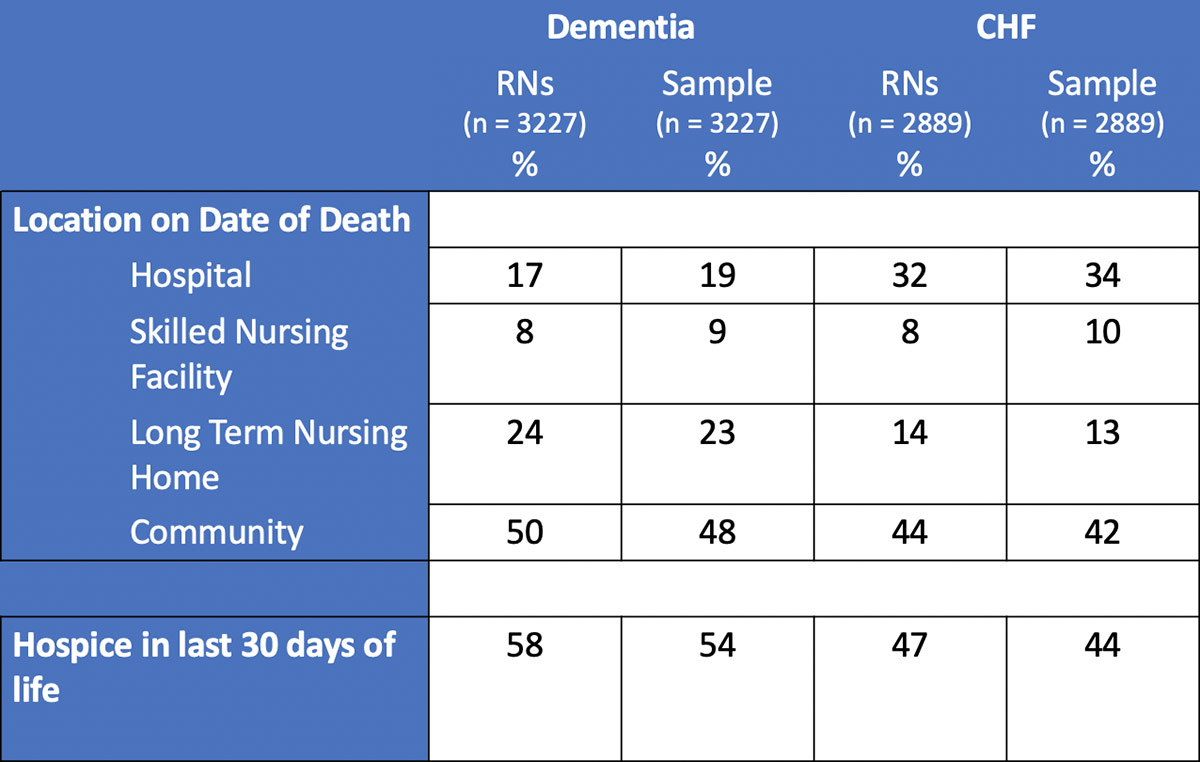

Overall, Julie’s study found small differences in end of life care as seen in the chart below for both dementia and CHF:

One can think of these numbers as so small of a difference that there really isn’t a difference. With that said, my favorite part of this interview is Julie’s take on this difference, which is that while the difference is small, there is a difference (“There is a signal!”). This means “I know it can be different, because it is different.”

by: Eric Widera

GeriPal is funded by Archstone Foundation. Archstone Foundation is a private grantmaking foundation whose mission is to prepare society in meeting the needs of an aging population.

Eric: Welcome to the GeriPal podcast. This is Eric Widera.

Alex: This is Alex Smith.

Eric: And Alex, we have two people on our Skype call with us.

Alex: We have two people on our Skype call. Our guest today is Julie Bynum who is Professor of Medicine at the University of Michigan in the geriatrics and palliative care division and the Institute for Healthcare Policy and Innovation. She is also a deputy editor at the journal of American Geriatrics Society. Welcome to the GeriPal podcast Julie.

Julie: Thank you. Delighted to be here.

Eric: And we’re going to be talking about your article that was published in JAGS, “Serious Illness and End of Life Treatments for Nurses Compared with the General Population. Do Nurses Die Differently?”

Alex: And speaking of nurses, we have a nurse on the line.

Eric: Who’s on the line with us?

Alex: We also have Lauren Hunt, who’s been a previous guest, host, many things on this podcast before. She’s a nurse practitioner. She’s worked in hospice. She is assistant professor in the School of Nursing here at UCSF in the Department of Physiologic Nursing and is an Atlantic Fellow for Equity and Brain Health in the Global Brain Health Institute. Welcome to the GeriPal podcast.

Lauren: Hi, glad to be here.

Alex: Good to have you back.

Lauren: Glad to be back.

Eric: And before we jump into this article, “Do Nurses Die Differently”? Do you have a song request for Alex, Julie?

Julie: Yeah. You know what’s the name of that song?

Alex: Well played. Well played. This will be our first, I think Sesame Street request. This is a Sesame street song.

Eric: This is a Sesame Street song.

Julie: Yes it is. You can see where my brain is.

Alex: So I was playing Sesame Street videos last night at home and my family was just snickering in the background.

Eric: Is this a common occurrence, Alex, or is just for this podcast?

Alex: No just for this podcast.

Eric: All right let’s hear it.

Alex: [singing] La de dah de dum, la de dah de dum, what’s the name of that song? La de dah de dum, la de dah de dum, what’s the name of that song? It goes la de dah de dum, la de dah de dum something, something, birds…

Alex: [singing] La de dah de dum, la de dah de dum, I wish I remember the words…

Eric: Okay Julie, why did you pick that song?

Julie: Oh, I just loved that little line I get to say when you asked me what song it was. I think mostly it was to make an excuse ahead of our conversation in case I have trouble with my word finding, which I often do.

Eric: Okay. So let’s jump into this topic of healthcare providers. Do they die any differently? How did you get interested in this? First of all, as a topic?

Julie: Well I’ve always been deeply interested in the role of physicians, nurses, clinicians in what we do for older adults. My interest is really about how do we get what older adults need and want to them. And I think the clinical professionals have a lot of influence there. But the real way this paper came together is through a wonderful collaboration with Fran Grodstein at the Nurses’ Health Study. So this was actually the offshoot of several other grants that we had. So basically the Nurses’ Health Study, if people know about it, they recruited 40 years ago, a very large cohort of nurses, over 100,000 followed them into older age and they’d been studied over and over again for disease. But I sort of turned it on its head and said, “Fran, why can’t we study them as nurses and what they do in the healthcare system? Can we actually flip this omelet and look at the other side for this cohort?”

Alex: That’s brilliant because as you say, everybody else is trying to say, “Oh no, this does generalize.” And you said, “Actually I’m interested in them now specifically because they are nurses.” It’s fascinating.

Julie: I’d like to mention that I’m a part of the Nurses’ Health Study. I guess it’s number three I think.

Alex: Really? Wow. So we have a participant here. Yes.

Julie: So the challenge for me then is for me to live long enough for you to be Medicare eligible so I can link your data to Medicare.

Lauren: That’s achievable.

Alex: So is this the first study that you’re looking at comparing nurses to the general public or have you used this dataset before for other studies?

Julie: This was the first study that we got grant funding for. The first idea, the first grant submitted. And really we wanted to study end of life care just as I sort of snickered about everybody using it to study disease. We wanted to study actually Alzheimer’s disease because there’s cognitive measures in the Nurses’ Health Study. But I was really bothered by the generalizability questions. So this became a win win because we could study generalizability as well as studying something interesting about nurses. So we have several other grants. We’ve had a grant in cancer care, in urinary incontinence and advanced care planning. And there’s another paper in JAGS out of the grant on urinary incontinence as well. And advanced care planning. So it’s been a fruitful relationship.

Alex: Not the relationship between urinary incontinence and advanced care planning. Just to clarify, right? Those are separate affairs.

Julie: Four separate grants, to be specific, four separate grants.

Alex: But why did you think nurses might die differently than the general population did? Is that clinical experience based on something you read? What led you to think this might be the case?

Julie: Yeah. You know it’s a little bit like the song I asked you to sing. It felt like it should be true. I feel like I know this song and I know the melody but there’s really no specifics around it. So that’s the case with the nurses. I think we have this gut sense that people who experienced the trials and tribulation of end of life care might do it differently. And there’s a bunch of studies on physicians but I thought, you know, nurses actually spend a lot more time one on one with families. So maybe if we’re going to see anything, maybe it’s the nurses who are really wising up to how to get the care they need and want.

Alex: No, I think it’s great because you know, even in talking to colleagues when we have difficult cases in the ICU or elsewhere, I think healthcare providers often talk about how they wouldn’t want this for themselves or you know, talking about how their end of life wishes would be very different. So I think culturally it seems like if I had to make a guess that providers die differently, nurses die differently based on their experiences seeing the bad things that happen. And so I think this is a great study. Like do they actually die differently?

Eric: Yeah. And Lauren what’s your perspective? I’m not asking you to represent all nurses or represent the Nurses’ Health Study?

Alex: Yeah since you’ll be answering this question…

Eric: But you know, have you also talked to other nurses and would you suspect out of the gates that nurses might die differently?

Lauren: I mean I think based on my own personal experience, the things that I was exposed to working in the hospital as a nurse changed my view about the end of life care experience that I would have wanted. I also agree, I think nurses are in a really unique position to be able to interact and influence patients because of their proximity and how much time they spend with patients.

Julie: And that proximity influenced some of my thinking on this because I can remember a case back when I was a resident where the team was really upset because a nurse had had a conversation with the family about advanced care planning absent the rest of the team. And the messages that came across weren’t the same as what the team would have said and it actually created a lot of conflict. So I think the idea of nurses being engaged in these conversations raised some really interesting interprofessional issues as well.

Lauren: Yeah. And I think what happens a lot of times is, you know, the team will have a conversation with the family and then the family is back in their room and the nurse is in the room and they’re helping the patient get their meal and giving them their meds. And then the family says to them, you know, they’ve been talking with me about this. What do you think about this? And what is your take and how should I move forward? And I actually think that a lot of nurses don’t feel empowered to have that conversation with families or don’t necessarily know how to, to move those conversations forward. So anyways, I think there’s a lot of opportunities for getting nurses engaged in these conversations.

Eric: Yeah. I always think about the movie Wit with Emma Thompson, where the nurse is sitting at the bedside sharing an ice cream Popsicle with Emma, and they’re having this heart to heart conversation about what she would want and how powerful that was.

Julie: But let’s keep in mind that the differences for the nurses actually as Dan Matlock wrote in an editorial said aren’t huge. There are some, and they’re actually bigger than they are for physicians. The physician studies are basically null, you know, showing very little different in end of life treatment. We’re showing there’s some signal here in nurses.

Eric: So let’s talk about your study. So again, this study was published in JAGS, Journal of American Geriatrics Society. What did you do in this study? Briefly, if you had to summarize it.

Julie: If I had to summarize it, unlike our other guest on the phone here, all of the participants in the Nurses’ Health Study wave that I used were all Medicare aged. So they were all enrolled in Medicare, which created this great opportunity where we could take all the survey data and link it to the Medicare claims data. But for this study what we really wanted to do was compare the nurses to people who were not nurses. So we had to use a cohort of people who weren’t in our dataset. So we created a national sample and we matched it using propensity matching to the nurses because you can imagine nurses are quite different from the average population. They have higher education, higher wealth, all those kinds of things. The racial distribution in the Nurses’ Health Study is different. So we had to make sure that the two groups were as similar as possible.

Julie: So we took the nurses who had their Medicare claims and met the eligibility criteria, match them to Medicare beneficiaries who are similar selected people with either Alzheimer’s disease or congestive heart failure serious enough to be hospitalized to choose two diseases that were really high likelihood of having important care management and advanced care planning issues and also a pretty high mortality rate in our observation period. And then we studied what happened to them in terms of their healthcare utilization in the first year of diagnosis and also in the last six months of life.

Lauren: I was wondering if you could talk about how you identified people with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementia and how you dealt with that in the different datasets.

Julie: Right. So for this study, what Lauren’s alluding to is for the Nurses’ Health Study, we have very rich, rich data including cognitive measures going way back, but we don’t have any of that for the Medicare data. So for this study, we actually didn’t use any of the survey data. We only used what was available in claims data. So that means using diagnostic codes on visits and hospitalizations. We did the same thing for congestive heart failure. For better or worse, we have a lot of information from studies for how accurate this is.

Julie: For Alzheimer’s disease, we tend to pick up later stage disease than you would if you did just a regular study in the population, not relying on claims. And for congestive heart failure, we have good evidence that our physician and nurse practitioner billing codes for congestive heart failure isn’t great either. But that’s why we required they had a hospitalization with the diagnosis to make sure these people really had congestive heart failure. So claims-based diagnoses and using the same criteria in both groups.

Lauren: Were there any people in both?

Julie: Yes. Yes, absolutely. Yes. And I suppose we could do a whole other study of multi morbidity in this population. That was an issue. We just, I mentioned propensity matching, so we included all these variables and we treated the two cohorts as if they were separate.

Eric: Okay. Can we jump to the results? Is it too early to jump to the results? Alex, you got anything else?

Alex: No.

Eric: All right, let’s jump to the results.

Julie: Oh, I’m going to tell you that. So I told you there’s two time periods we looked at, we looked at when people were first diagnosed or at least right after the hospitalization for congestive heart failure. And we looked at the six months before the end of life. Which do you want to talk about first?

Eric: Well let’s talk about the after the diagnosis.

Julie: There’s no difference.

Eric: No difference. Utilization, hospitalizations, all of that… The same?

Julie: Pretty much the same. Yeah. So one of the things to keep in mind in the kind of research that I do, I have what I would describe as ginormous sample sizes. So we often have statistical significance but not clinically meaningful difference. So I think basically the nurses and the congestive heart… The nurses with dementia and congestive heart failure had the same number of hospitalizations, emergency visits, primary care visits. There was a very slight difference in specialty care visits. And that’s actually a line… I mentioned the other studies we’ve done, we’ve also examined the issue of nurses’ behavior and visits in other contexts. And we find the same thing that they tend to use specialists a little bit more than the general population, whether that’s access, knowledge, friendships with specialists or not, who knows? So that was really the only difference, which was frankly a bit surprising.

Eric: Yeah. Well why were you surprised by that?

Julie: Well, again, like everything we’re saying, nurses have high health literacy and if anybody should be able to behave and get their health care management going well, this group should. But maybe that assumption isn’t true and maybe there’s a cohort effect. These are nurses who are all over 65 and trained a long time ago. And actually I’m going to pull up the average age of the sample here. These people are in their eighties at this point. So maybe our conceptualization of a nurse today is a little different from the cohort effect that we might be seeing in this study too.

Alex: Did you see any differences for end of life utilization, hospitalizations, ER…?

Julie: So at the end of life it gets very interesting. So basically we find slightly less acute care use, a little bit less use of the hospital, but the big findings were really in the intensive use at the end of life, not just utilization. So visits, nursing home use, skilled nursing use. That was all pretty much the same. But what we found was that the use of aggressive treatments like life-prolonging treatments, ventilators, feeding tubes and having a terminal hospitalization that included an ICU stay, which means you died during a hospital stay that included an ICU stay. Those were actually less common in the nurses than in the general population.

Eric: A lot or a little?

Julie: A little, I mean, how do you compare means of a population? Right? We can get into some really wonky statistical stuff. I mean to find any signal here is actually, I think good to be able to see any signal. But this is not a whopping difference. It’s you know, a 2% to 3% absolute difference in the percent of people who have life-prolonging treatments or terminal hospitalizations and they were ever so slightly more likely to use hospice.

Alex: Mmm. So really small differences here and I just want to point out one unique feature of this study is… so retrospective studies of decedents are often criticized and were criticized famously in JAMA in an article by Peter Bach, you know, resuscitating treatment histories of dead patients, you know, methodology that should be laid to rest, something like that with his cheeky title. But you sort of did this prospectively looking at the year after diagnosis as well as retrospectively looking at the end of life experience of these nurses. I wonder if you have some comment on that approach.

Julie: Yeah, it actually was a… how do you define this as prospective or retrospective? What we first did was identify people with the new diagnosis and then we followed them prospectively, found the people who died and described the death experience. So I suppose it’s a mix of the two methods. Part of the reason we did this was to address some of the biases that you might assume were present if you only looked at decedents and professionals and that the prior studies that looked at physicians. One didn’t do it disease specific, two didn’t look at longterm care and three didn’t look at the time of new diagnosis.

Julie: Because one thing you might guess is maybe what if nurses were diagnosed earlier or had more uses of the specialists for example, that might alter their trajectory at the end of life just because of the inputs earlier. So we looked at that specifically to try to address that potential bias and differences we might see. We were also interested in the earlier course because as you know we say at the end of the paper we want to be able to study nurses in general. We really wanted the data to be generalizable because we want to continue to use this data. So I guess we actually won on both crowns because it’s generalizable in some contexts and a little bit different in some narrow specific cases.

Alex: Right. And I’m interested to hear what you make of these findings. You know, as Dan Matlock and Stacy Fisher wrote in their editorial in JAGS that accompanies your study, unquestionably the differences in end of life care patterns are statistically significant and clinically meaningful, but they’re unremarkable. Talking about these two to 4% differences, what do you make of these findings? Did this surprise you? Were you like, “Wait, there must be something wrong with the data.” Or…

Julie: Yeah, it’s really good to be an equipoise when you’re heading out to do a study, right? So I had two goals here, two conflicting goals. I really wanted them to be no different so I could use this data to study anything and everything under the sun in healthcare utilization. I would love to be able to use the survey questions 40 years ago to understand something about late life illness and death. That’d be wonderful. At the same time, to write this paper, a big splashy paper, you’d want a big difference. Right? And so what we really found was we didn’t find a big difference. We found a place where we’d need to use a little bit of caution at the end of life with the most aggressive care. Maybe nurses aren’t quite generalizable. Maybe they’re not quite generalizable on their specialty use.

Julie: But the magnitude of differences is small. And I think we can use this cohort for lots of other interesting studies. But my big takeaway on the general point is that this paper… I feel it’s important, not so much for the magnitude of difference, but to raise the point that we focus so much on physicians and how they experience death. But this paper we were able to get on the table with data, the role of nurses. So it had sort of a double edge, right? Something about advanced care planning. But also we were able to make the point, say, “Hey, what are those interdisciplinary and other challenges?”

Alex: This is a really important point here. You know, Stacy Fisher and Dan Matlock published a previous paper that you’ve talked about about how doctors died… don’t die differently actually, also in JAGS. And so I was a coauthor on that paper and we sent it first to the New England Journal. Then we sent it to JAMA, you know… It found a home and a great home at JAGS as it should and maybe we should’ve gone there first because it’s an awesome journal. Go JAGS. But one of the critiques that we consistently faced is that when you’re looking at older doctors who die, they’re overwhelmingly men. And might this not only be a generational issue as you mentioned earlier, but also a gender issue and your study addresses that issue. If you’re talking about health professionals as a whole because your study was overwhelmingly women I would say.

Julie: It was only women. Nurses’ Health Study. However, go ahead.

Lauren: Were you going to?

Julie: I said however, what we did was we added a cohort of men, so the main analyses are all presented of nurses who are all women compared to women, but then we did a supplementary analysis with men to see how much differences there are. And there are some differences that are probably more gender related, but again we don’t see huge differences. The differences we do see are around use of home care and nursing home, which is pretty interesting if somebody is interested in going down that path of how men and women use longterm care differently at the end of life.

Alex: I haven’t looked this up but one of my, so I probably shouldn’t cite it on a podcast, but I’m going to go do that anyway. Guy Micco, who’s a geriatrician palliative care doc at Berkeley and was on this podcast previously said that he read a study where the primary predictor of sort of the end of the life course of somebody is whether they had more than one daughter. So certainly there are gender stories here around whether the man is dying or the woman’s dying. And that is certainly a place we could go. It sounded like you had some comment on that.

Julie: Yeah, I think that’s exactly right. I mean I think the gender differences are probably more around family structure and who’s who’s widowed and who’s not. And I just want to call out another paper that has come out of our group with the Nurses’ Health Study that wasn’t linked to claims that also came out here was to show that advanced care planning rates in nurses are extraordinarily high. So the presence of a written advanced directive in the cohort in this study is about 84%.

Alex: Wow. Yeah.

Julie: So that really raises another question. I think Dan’s and Stacey’s editorial was bang on. The things that we think should matter. Health literacy, experience with the health system, having a written advanced directive, they don’t really seem to matter very much. So then what will matter? And then we can start talking about, you know, turning the system upside down in terms of what we think can change things. I have another paper where we studied CCRC, continuing care retirement communities, if you’re familiar with those. And a particular one that had primary care totally embedded and we found the percent of people who died in the hospital was only 5%. Extraordinarily low, a totally out of the box model, but they achieved a completely different end of life trajectory.

Alex: And that’s compared to about 20% of the general population who die in the hospital.

Julie: 20% or in CCRCs is around 13% that we compare it to. So yeah.

Lauren: Yeah, I thought the editorial brought up a really interesting point saying that the obvious question is that if you have only these small differences in a group of individuals who are exposed to the healthcare system and know all of the carnage that’s associated with it and… Like me at work had a lot of moral distress from witnessing people’s end of life experience. You know how do we change things in the end?

Julie: Yeah. Well and one of the things I would say the editorial is like, glass is 90% empty. And I’m saying, well maybe it’s 25% full. You know, I’m not saying this is a great thing, but you know, we actually are seeing a different… One of the things that struck me is the magnitude of effects and the strength of the relationships was stronger for Alzheimer’s disease than it was for congestive heart failure. And I don’t think we should minimize that. I think there are real differences in the way we’re willing to pull back in various different kinds of conditions. And so I don’t know that we can think about serious illness with one broad stroke, that everything should have the same path and the same trajectory, that we need to be more nuanced in thinking about that.

Julie: And you know, until you have a a system where people can really be someplace that’s not the hospital and not be a burden to their family, be in their own home, it’s going to be really hard to change these trajectories because no one wants to suffer but no one also wants to bring their family along with them. And so that’s a hard nut to crack in our system.

Eric: Now when you look at this data, again, whether or not it’s 75% empty or 25% full, relatively small changes or differences between the two groups and if you look at the information coming out of the Dartmouth Atlas and how what matters for healthcare utilization is not just patient preferences, their experiences, but also where you live, what hospital catchment area you’re in, what state you’re in, what city you’re in, how many ICU beds does your referral region have, how do you think about combining these two pieces of data?

Alex: This is a perfect question for Julie Bynum. You like that?

Julie: I’m checking something right now. But just to say in this study, I believe we did this and now I’m going to refer back to that song I asked you to sing. When we do propensity matching on any of my studies, we match on region. So that we actually remove that effect from these studies when we include that in our propensity matching. But you’re right, I mean that speaks to both… People will say culture and norms. I think there’s something very specific about healthcare norms and physician practice norms that we as the clinicians and nurse practitioners, we’re not even aware of what influences us and that’s what I take away very much from the Dartmouth Atlas.

Julie: Again, I try to be the… Maybe I’m even up to a half cup full with this message, is that the biggest thing I remember when I first learned about Jack Wennberg and the Dartmouth Atlas and the biggest thing I’ve always taken away from it is that when you see those large differences, what it means is it can be different, right? I know it can be different because it is different. It is different in Oregon than it is in Manhattan. Therefore, I know it’s possible to have something different because it already is. And that’s always been the angle I’ve taken on the Dartmouth Atlas, well if they can do it that way, what are they doing? Not just to say, hey, there’s variation, but what can we learn? How can we use this as a tool to figure out the secret sauce, right?

Eric: But also just how important and influential those cultural and practice norms are and how we need to take those into account and how difficult those actually are to change in practice and reality.

Julie: Am I allowed to blatantly call out another of my paper in JAGS.

Eric: Just go for it.

Alex: Yeah.

Julie: A PSA screening test in men over 75 paper that I had this last year studied by region. The average nationally hasn’t budged basically and men over 75 but when you look by region, you see places that have dropped dramatically and places that have actually risen over the last decade. It’s an amazingly impactful concept that healthcare is different from place to place.

Alex: So what do you think? So it’s good to know, and I like this flipping the Dartmouth Atlas on its head, a little bit, findings to say that actually that means that there actually is potential for change.

Eric: There’s hope.

Alex: There is hope. Where before there was only darkness… But what do you think is in the secret sauce? What do you think we need to do differently?

Eric: Because you’re an optimist, Julie. I like that. Let’s hear from the optimist.

Julie: Well, okay, let’s go back to the study, the optimist version of this study. The nurses were studying in this report, we’re seeing a signal. There is a signal there, right? It’s not big, but it’s there and these are women who were nurses 40 years ago. If we think about Lauren and what she’s going to be like, I’m going to guess, let me, I’m not going to try to guess her age, in 50, 60, 70 years from now, how different her choice set will be and her empowerment to make changes in her own care. So this is obviously incredibly incremental, but it is a signal that people are responding to something. Nurses are responding to something, at least in the context of the most intensive treatments in a very progressive, terrible disease of Alzheimer’s.

Eric: Yeah. And I really liked the study because I could also imagine a world where you found the opposite. Where you found that health care providers actually use more intensive resources throughout their illness and death. I recently, what, like six months ago, I had a mild case of Bell’s palsy that went away after a couple of weeks and I saw a neurologist, a primary care doctor, a specialist neurologist who has both a neurology and a radiology ex… Like it was just the amount of stuff that I used for a mild Bell’s palsy, which was shocking in hindsight to me. And I certainly did. I just needed to see my PCP. So I can imagine a world where with healthcare providers, you have often much easier access to the healthcare world. You know how to navigate it, you know how to get quick appointments. And most of the general population, they don’t have that access. So I can imagine a world where you saw opposite findings.

Julie: Absolutely. And in fact the one study, I think Alex, it’s the one you were on, showed that the physicians used more ICU care.

Alex: Yeah, that’s right.

Julie: Right. So I mean, as a clinician… Some level, we all went through this training and we have a belief in medicine, right? We’re not people who have turned away from the healthcare system, we’re people who believe in it. So maybe we’re the hardest group to change?

Alex: Right? So in that study it was sort of more of everything, right? More ICU, more hospice, more of everything. But yeah, we know how to navigate the system as you say Eric.

Lauren: Julie, do you think that there’ll be opportunities to study different cohorts in the Nurses’ Health Study to look at these trends over time and whether things are changing with the newer nursing generation?

Julie: Right. That’s a good question. So, you know, women have really long life expectancies. So in your research career, if you can live until when Nurses’ Health two makes it to Medicare age, we can look at the cohort effects. I mean that’s one of the challenges of this kind of study right? Hopefully… These women had to age into Medicare. That’s why nobody could do this before and the data had to be available. It’d be wonderful if we could take healthcare data for the current cohorts and examine these trends. I mean the problem with utilization studies on self-report just doesn’t work that well. But I do think we can learn something by studying these groups well.

Lauren: I wonder if there’s also opportunities to include in the Nurses’ Health Survey. I don’t know if they do already, but questions about preferences for end of life treatment because then you know, in whatever 40 years somebody could study.

Julie: Funny you should ask that. So our other paper is in fact those questions. We have a paper, that’s how we know about the advanced directives and the last wave that went into the field added additional questions. Fran Grodstein has had a change of career and I have had a change of career. I’ve moved from Dartmouth to Michigan for those who didn’t understand what those allusions were to. Fran is making a professional change to and we’re trying to sort of regather our troops and figure out where to go with this moving forward because we do think this is a fabulous opportunity.

Eric: Well Julia, I want to thank you for joining us on this podcast.

Alex: Thank you so much Julie.

Eric: If you can summarize one or two take home points for our audience about your paper or the conclusion that we should be drawing from it, what would those one or two things be?

Julie: I think that that nurses are an important team member who have knowledge about healthcare and we should be thinking seriously about them as a team member, as we try to alter the course and get people what they need and want in serious illness. And we have a little hint that nurses might be doing it for themselves to some degree.

Eric: Yeah, we’re seeing a change. We’re seeing a small change, but we’re seeing a change. That means that we can change things.

Julie: I like the way you think, Eric.

Eric: Well I just listened to you and I love the optimism. So again, thank you. But before we leave, Alex, do you want to end us? What was the name of the song?

Alex: [singing] What’s the name of that song? La de da de dum, la de da de dum, what’s the name of that song? La de da de dum, la de da de dum, what’s the name of that song? It’s called… No wait, I think I’ve got it! Oh no, that must be wrong. La de da de dum, la de da de dum, what’s the name of that song?

Eric: And with that, a big thank you both to Julia and Lauren for joining us today as well as all of our listeners for joining us on the podcast. And a very big thank you to the Archstone Foundation. This podcast is made possible from a grant from the Archstone Foundation, and we really appreciate their support.

Alex: Thanks folks, bye.