Comics. Cartoons. Graphic Novels. Graphic Medicine. I’m not sure what to title this podcast but I’ve been looking forward to it for some time. Heck, I’m not even sure to call it a podcast, as I think to get the most out of it you should watch it on YouTube.

Why, because today we have Nathan Gray joining us. Nathan is a Palliative Care doctor and an assistant professor of Medicine at Johns Hopkins. He uses comics and other artwork to share his experiences in palliative care and educate others about topics like empathy and communication skills. His work has been published in places like the L.A. Times, The BMJ, and Annals of Internal Medicine.

We go through a lot of his work, including some of the comics below. However if you want to take a deeper dive, check out his website “The Ink Vessel” or his amazing twitter feed which has a lot of his work in it.

Eric: Welcome to the GeriPal podcast. This is Eric Widera.

Alex: … I was muted. This is Alex Smith. You’d think I learned to do this? Haven’t we done like 200 of these? [laughter]

Eric: Alex, I forget what happens next. Oh, wait, we have a guest with us.

Alex: We do. I threw everything off. We are delighted to welcome Nathan Gray, who’s a palliative care doctor, Assistant Professor of Medicine at Hopkins Bayview, and is a graphic artist extraordinaire. Welcome to the GeriPal podcast, Nathan.

Nathan: Hello, excited to be here.

Eric: I’m looking forward to talking about art and humor in palliative care and we’re caring for seriously ill patients. But before we do, we always start off with the song request. Nathan, you got a song request?

Nathan: I do. So first thing people think of when they think of cartoons or comics is superheroes. And so I would love to hear Superman, by Five for Fighting.

Alex: Excellent.

Alex: (singing)

Eric: I love that song.

Nathan: That’s awesome.

Eric: This is a word to all of our listeners. So you can certainly listen to this podcast on your favorite podcasting format. However, we really encourage you to check out our YouTube site for this podcast, because we’re going to be sharing some of Nathan’s graphic… So Nathan, should I call it comic, should I call it graphic art, should I call it cartoons? What should I call this?

Nathan: It’s been called all of those things and more. I’m really comfortable with whatever term people want to use. I’ve found that different audiences prefer to call it something different. But yeah, comics or cartoons is probably the easiest way to catch all.

Eric: All right, I’m going to call it comics. So really encourage all of our listeners to listen to this podcast and watch it on YouTube so you can see some of Nathan’s amazing comics, which we’ll be discussing today. We’re going to be sharing those comics and exploring how Nathan uses humor in art, in the work that he does. And this is part of our ongoing series. We’ve had two podcast already on poems in both aging and in palliative care. I think this is a nice complement to that. And Nathan, before we jump into how you got interested in it, I’m going to share one of my favorite comics. See, I’m still struggling exactly what to call this.

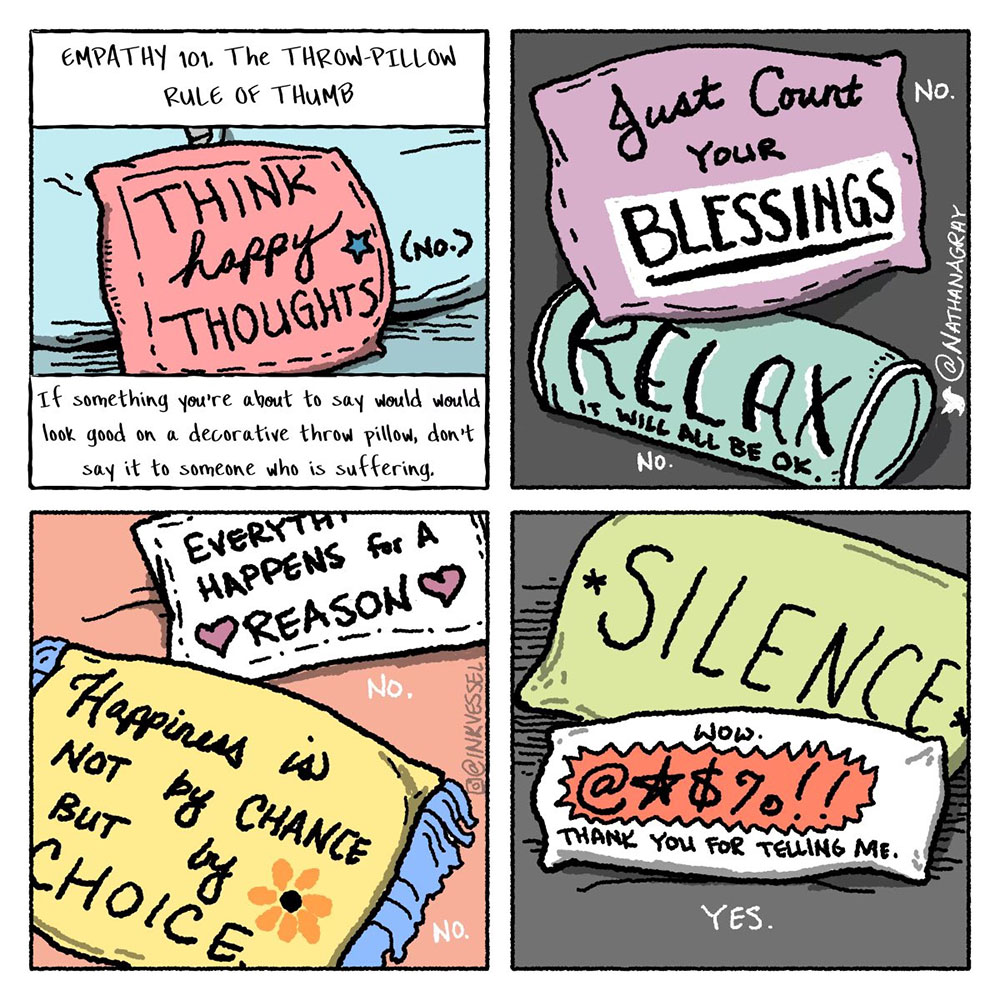

Eric: And this one just came out. I’m going to share my screen and we can talk about that. I saw on your Twitter page, this comic. And I’m just going to explain it to our listeners, what I’m seeing on my screen. So this is an Empathy 101, The Throw-Pillow Rule of Thumb. So very first throw pillow, think happy thoughts. And below it says, “If something you’re about to say would look good on a decorative throw pillow, don’t say it to someone who is suffering.” Again, first is think happy thoughts. Second is just count your blessings. Relax, it will all be okay, with a big no next to both of us. Oh no, no, no. And the third panel says, “Happiness is not by chance, but by choice,” which is a big no. Another one says, “Everything happens for a reason,” with a big no. And then the last panel says, “Yes,” and there’s a throw pillow with silence and a throw pillow with, “Wow,” a bleeped out word, “Thank you for telling me.” So Nathan, tell me how you came up with this and how you you thinking about it?

Nathan: Yeah, I, like all of us, struggle at times when there’s a profound silence and there’s this really inhuman temptation to fill it up with something that we think might make somebody feel better or makes us feel better. And very rarely is that helpful to the person who’s suffering. And so when I built this comic, I actually Google searched throw pillows with motivational quotes. And all of these, except the last two, were throw pillows. I didn’t see any throw pillows with profanity on them. But sometimes when somebody’s really suffering, that’s what they need is not the motivational quote. And I’ve heard this said in other forms, like don’t give people a platitude when what they need is just your presence. And this cartoon really is a sticky way for me to sort of communicate that to others. A cartoon has a certain hook to it that you remember in a way of somebody just gave you a lecture and said, don’t give a motivational quote if somebody’s hurting. You might not remember it. But the cartoon sticks with you, the colors that the profanity bleeped out. That stuff really grabs you.

Eric: How long have you been doing these cartoons?

Nathan: I have drawn for my entire life, but I gave up cartoons because I thought I had to during medical school and residency. I thought doctors are serious, cartoons are not serious. And if I want to be a serious doctor, it means I got to leave that behind. But if you look at my lecture notes from medical school, it’s just plastered with cartoons and doodles. It was in there just trying to escape. And late in residency, I was really burnt out. And so I turned back to cartoons and they were really dark. If you look back to some of my cartoons from late in residency, they showed just how dehumanized I felt and definitely give windows into how dehumanized I imagined my patients to be.

Nathan: And so it’s interesting because it really reflected things now, looking back that I can see that I didn’t even realize at the time. So I got back into it anonymously. I started making cartoons, occasionally I would post them online. And a doc over in Spain named Monica Lalanda, who is an ER doc and also a cartoonist, reached out to me and said you don’t have to do this anonymously. This could be something that meshes with your life and medicine. That blew my mind. And I found out there’s other doctors out there making comics, making cartoons and finding ways to weave that in to their life in medicine, and it’s been really rewarding.

Eric: Do you think it’s helped at all in your academic career?

Nathan: It has. The fact that my cartoons, thanks to social media, I’m able to sort of get them out there in front of people. It’s a really niche audience and humor, especially. I appreciate the gratitude I get from the broader medical society, but palliative care is a small world. And so getting to put those cartoons in front of people is really rewarding and it’s allowed me to get my work out there in front of people as well.

Eric: Speaking of a niche humor, I love this one. So for those listening to the podcast, this is a clown looking very sad and what looks like a hospital administrator. And the hospital administrator says, “No, the hospital definitely values your contributions to the interdisciplinary team. We just don’t value them in a monetary sort of way.”

Nathan: The clown is a surrogate. Clearly, I’ve never been a part of an interdisciplinary team that had a clown on it. But I know that feeling, in talking with other interdisciplinary team members of feeling like they were valued in a verbal way, but not in a monetary sort of way. And this cartoon was a really sideways way to parody our skewed way of assigning value in modern medical culture.

Eric: So let me ask you another question. So humor like this has a lot of potential benefits. I think this, you got to have to know a little bit to really understand this. What are your thoughts about using humor to convey ideas, thoughts, clinical work?

Nathan: Yeah, I think it has to be a really, really sensitive and cautious act. So I’m really pretty protective of how I do my cartooning process in a way, in that I have a sort of small group of people that I can share cartoons with and bounce ideas off. Because just like in the bedside space, if you are using humor in a way that builds bonds and relationships with the patient can be really beautiful, and normalizing. Patients will tell our team after we’ve been through, “Oh, I just love that I was able to laugh with you guys. It felt normal again after being sick and having people look at me with pity for so long.” That said, humor is really dangerous. It’s a two edged sword. So if humor belittles people or puts them in a space of being othered, it’s not fun. So when I make a cartoon, usually I’m sending it to a few people before it’s ever seeing the light of social media, to make sure it’s not going to come across as insensitive either to patients or to my fellow providers. You never want to be punching down.

Nathan: And there’s a small subset of palliative care humor, which is dark and is probably best shared in a team room amongst a few people and not necessarily put out there for the light of day. I think that there are times when we use humor to cope, and that’s a special and very tender space for of people to share in, but is not something that you want to expose to the light of the world. So I’m always looking for feedback before a comment goes out there and making sure that I’ve been attentive to how people are portrayed.

Eric: Now, talking-

Alex: I’m just going to share this one. I love this one. Can I describe this one?

Eric: Yeah.

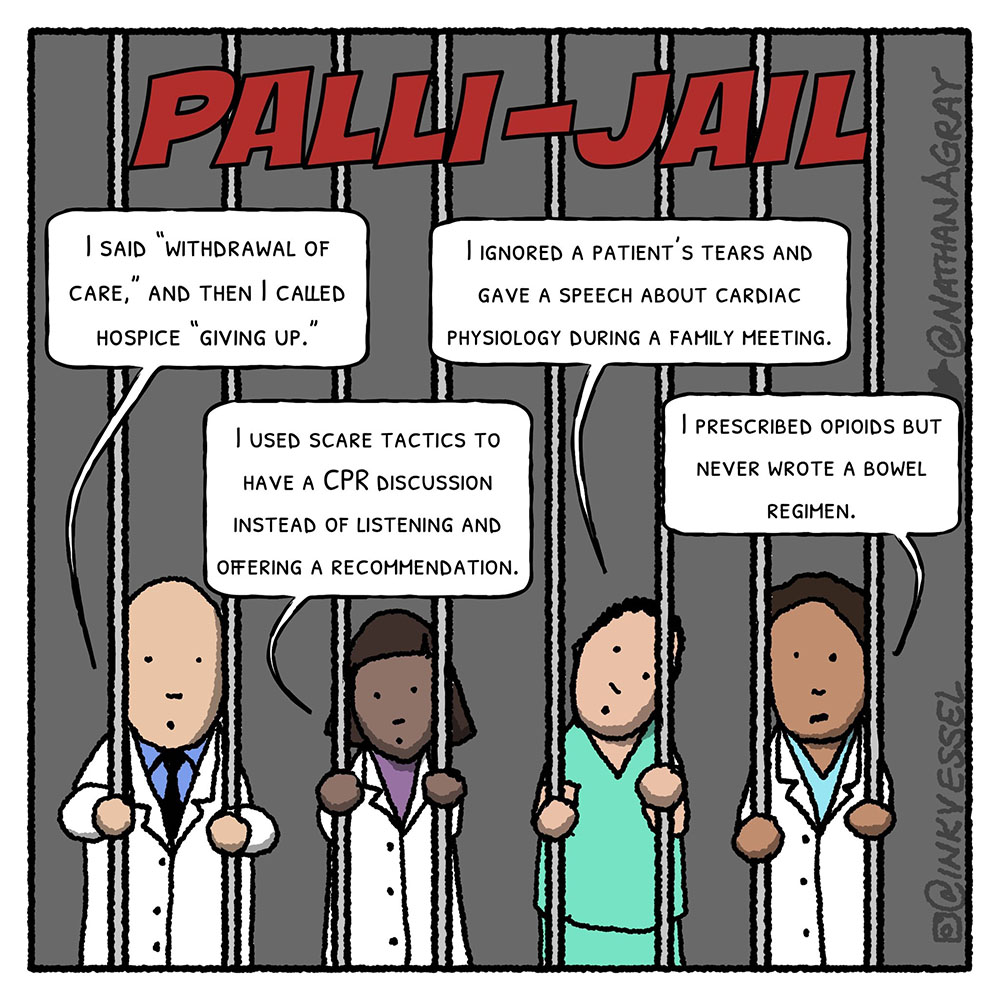

Alex: Your work is sometimes directed at teaching people about the better language to use, like that first example of don’t say things you’d see on a throw pillow. This is another. We have all made mistakes in the language we use, the words we use and sometimes, in palliative care or in care of people with serious illness, that puts us in jail. We feel like we deserve to be in palliative care jail. And so here’s a picture of four healthcare providers behind bars. And at the top it says, “Pali-Jail.” The first healthcare provider said, “I said withdrawal of care. Like, oh no, I said it. And then, “I call hospice giving up.” We have all been there, been put in palliative care jail, said those words. And we’re like, wait, I teach people not to say that. I did it, oh no, what happened?

Alex: Here’s another. Another clinician’s saying, “I use scare tactics to have a CPR discussion instead of listening and offering a recommendation.” Been there done that too. I used to say this horrible things like we don’t want to push on your chest, crack your ribs, crack open your chest, massage your heart. That’s scare tactics. Here’s another clinician saying, “I ignored a patient’s tears and gave a speech about cardiac physiology during a family meeting.” That’s a safe space for so many people is to go back to the physiology. And then the last, clinician says, “I prescribed opioids, but never wrote a bowel regimen.” Definitely puts you in palliative care jail. Definitely puts you in palliative care jail. So I wonder Nathan, comment, if you could for us, on these comics, graphic art as a mechanism for teaching people, whether it’s within the palliative care community or the broader audience of clinicians that this clearly would appeal to as well.

Nathan: Yeah. There’s that stickiness of comics and being able to do something in a way that I’ve given people a lecture about things not to do, but I’ve done it in sort of a confessional way of like, I’ve been in that jail before where I felt like I needed to. Like, it felt good to me to talk about the opioid receptor in that moment, even though somebody was crying and I really wanted to talk about how cool it is that we have a selective opioid receptor for the bowels, or a selective opioid antagonist for the bowels.

Eric: That is pretty darn cool.

Nathan: Right. It’s cool and it’s fun for us. And it gives us a way to alleviate from some of the discomfort. But the reason this works, I think to sort of communicate is because we’ve all been there. And I think we hold ourselves often to a pretty high standard for communication in palliative care. And sometimes that standard is so high, we have to acknowledge that there are going to be times when we stick our feet in our mouth because we’re human. And so for me, this was saying like I may give lectures in my cartoons about things I think that are good and bad, but a lot of them are things I’ve messed up on, I’ve done this. I’ve been the one to say a word that didn’t land like I hoped it would.

Eric: Yeah. There’s a need for humility, a lot in the work that we do. I was just thinking back to yesterday, we were in a family meeting. Somebody asked the question. I was very focused on like one answer and completely missed the main point of the question. But luckily, Anne Kelly, our social worker, was in the room with me and said the magic thing that just was the right thing to say. And as she was saying, well, yep, that was the right response to that question. And to recognize that we all have our blind spots, we have all our focuses and the really key need for an interprofessional team, going back to your last comment.

Nathan: Yeah. It’s an interesting thing because I initially, a lot of my comments lately have been these sort of Instagramable four block comics. That’s how I initially designed that one. And then I felt like they should all be in jail together, in one cell. Like you’re saying, we need each other in that cell together to see each other’s blind spots, to confess to each other where we’ve failed and to see that and move forward.

Eric: Yeah. And there is that, like we were talking about before, there’s using humor for a lot of different reasons, including within your own team, the inside humor, the laughs that we have outside of patient’s rooms about, like we talked about what happened of all like thank God Anne Kelly was there to say the right thing when that was needed. And yeah, using again, humility and humor in the right setting can be very helpful. And then also potentially from an educational standpoint. So I’m completely dominating this. I’m not even allowing Alex to share any of his favorites. Nathan, you want to tell me about this one?

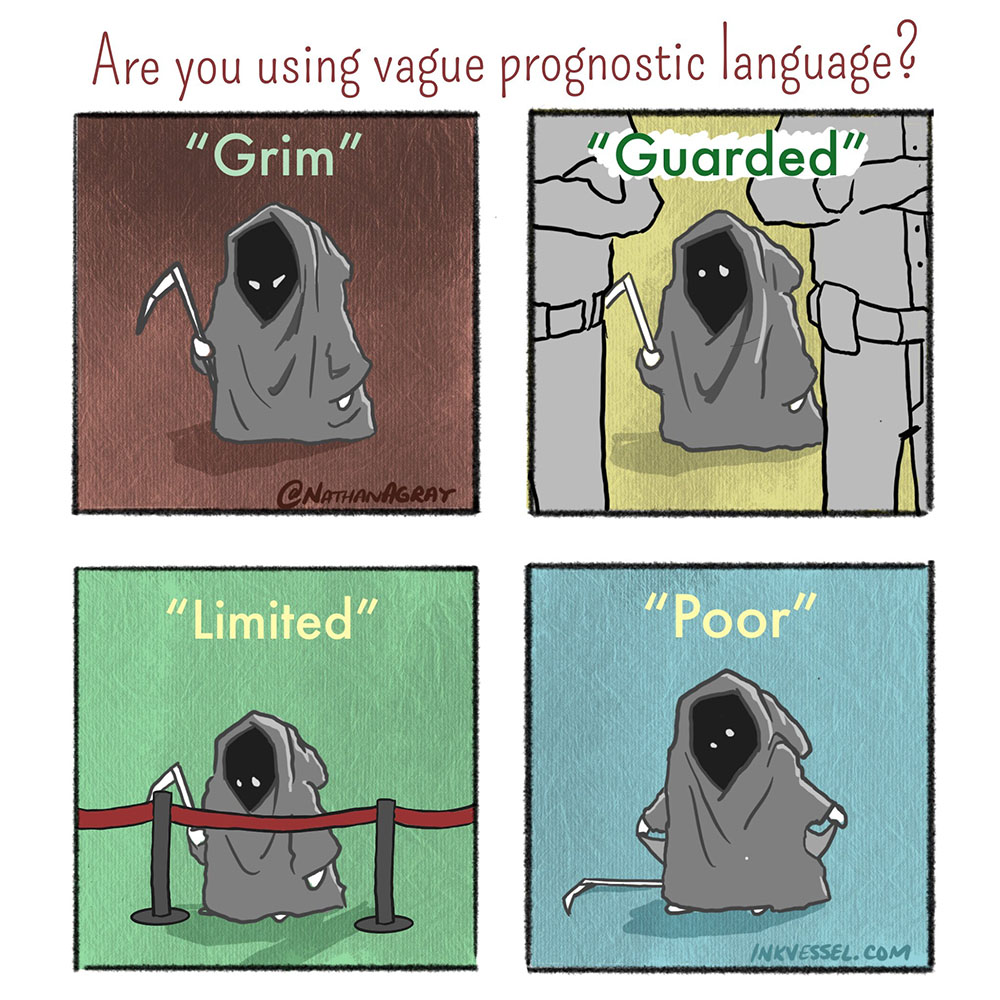

Nathan: So this one across the top says, “Are you using vague prognostic language?” And it has four boxes beneath in various colors and shades. And in each box, there’s a little cute baby Grim Reaper.

Eric: Very cute by the way.

Nathan: Yeah, thank you. Above that Grim Reaper, there’s a quote that I’ve heard for a word describing prognosis. And if you look through a medical chart for a patient with serious illness, you’ll find these words all over the place and we say them aloud. So one word is grim and you can see the Grim Reaper has got his eyes sort of crossed and slanted. You see the guarded prognosis in the next panel. And there’s two security guards in front of the Grim Reaper. I don’t know exactly what I had in mind here, but it almost looks like the Grim Reaper is not being allowed to get on a ride at Disneyland.

Eric: I thought they couldn’t get to a club. [laughter]

Nathan: Maybe that’s it. He couldn’t get out for a night out on town. Didn’t know the right people. And the last one is poor. And the Grim Reaper is pulling his pockets out to show that he’s got empty pocket.

Eric: And I love this one because I was just talking to, I forgot who it was, about the use of prognostic language, how a lot of the words that we use are just unhelpful. Like telling somebody their prognosis is poor, what is that? Is that hours, days, weeks, months, years, decades. If you told me I had years, I would say that was poor, but you may thinking poor is like days or weeks. So this one really hit home for me as a great educational tool. And also for me too, just to remind myself whenever I’m in those situations, not to use, like poor, I hear so much.

Nathan: Yeah. And I spent a while trying to figure out how I wanted to make this point. And one of the reasons I think cartoons work really well for serious topics is because they approach it in a way that makes it accessible and perhaps a little less scary than it could be. So again, when I make the Grim Reaper adorable, it makes it easier to talk about in a way for providers. Again, there’s the hook of that like Grim Reaper sticks in your head. But it also makes it a little easier. Because really, when we use those words, a lot of times what we might be saying is that a person is in the last stages of dying. And so to use the Grim Reaper and say, is he guarded, is he poor, is he limited, are all those words just talking about the same Grim Reaper.

Eric: Do you use this also in more formal education? Like when you’re with med students, residents, interns, do you use your graphic novels, comics?

Nathan: Yeah. I definitely use comics to spice up talks when I’m giving talks. Comics can be a little hard. It’s one of the reasons why I was intrigued to see how this podcast would go. It’s hard to talk about a comic. There’s an inherent, personal connection that a person who’s viewing a comic has with that artwork, where they’re going to move through it at their own pace. They’re going to take the panels at their own pace.

Nathan: That’s why if somebody puts a Far Side comic up on a PowerPoint and reads it to you, everybody starts laughing at the room in different times. And some people don’t laugh at all, because it’s the Far Side. But we all approach them in our own way. So I tend to use them on a sort of limited basis in talks. I don’t let them dominate the talk. I very rarely use them at the bedside. Occasionally, people will come to me and say, like when I’m meeting them in the clinic and say, “Hey, we Googled you. That’s so cool that you make cartoons.” And I thankfully haven’t had anybody decline an appointment or something that I knew of because I did this.

Alex: Let me share one here.

Eric: You beat me into the punch this time. I had one ready.

Alex: Could you walk us through this one, stages of grief in era of immunotherapy?

Nathan: Yeah. So this is from probably six or seven years ago. I spent a lot of time in one of my previous roles working in the inpatient oncology unit as a palliative care inpatient provider. It was the early stages of immunotherapy being applied to a lot of new cancer types. And it seemed like we had created a new stage of grief. So the graph, it’s sort of a snake-like pattern of war and what you see as denial, anger, bargaining. And then there’s this explosion of nivolumab and then grief and acceptance. And it felt like we had sort of chain change the arc of serious illness with this nivolumab piece or other immunotherapies, not singling out nivolumab, where we have this new drug and we’re all still learning how it works. It takes a little while to work.

Nathan: And so sometimes grief and acceptance seemed like they were getting delayed by our growing understanding of how immunotherapy works. This said, I’m still a big immunotherapy fan. This came actually out of a conversation that we were having in a workroom where we were saying, it sounds almost like we’ve created this new stage of grief. And the next day, I was like, here, look, I made a comic of it.

Alex: Right. Your work fuels your comics. And that’s like, so I’m a researcher. The best ideas for research come from my clinical experience. And it sounds like the best ideas for your comics come from your clinical experience from talking with interdisciplinary teams, from the interactions you have with patients, from mistakes you’ve made, from teaching you’ve done. Does that sound?

Nathan: Yeah. Every day I try to keep a sort of running tally of comics that I need to make so that anytime I have a creative block, I’ve got this little reserve of ideas I’ve had as I’ve been walking around through the hospital. And it also gives me a little space and time to decide whether those ideas should see the light of day. Because some of them, again, you have a dark thought or a dark humor moment and a little space in time and say, okay, yeah, that’s funny to me, but that’s not going to work for the broader audience.

Alex: All right. Speaking of dark humor, I’m going to show the one that I just love pulling this one up because, like we were talking about before, the work that we do, there are some themes that you don’t know, like is this just like my own local institution or is this like a theme everywhere? Nathan, you want to describe this one for me?

Nathan: So in talking with others is common scenario. So this is the genre is supposed to feel a little more action here. You’ve got two providers talking. One says, “I’ve got a patient that I want you to put on the radar.” The palliative care provider says, “Oh, okay, go ahead.” Next scene is red with the physician running through the halls. And it says moments later, flings open the door of the palliative care workroom and says, “Quick guys, there’s a man suffering on the 12th floor. Put him on our radar.” So that you can see the technicians there at the radar. And they say, “Sir, 12th floor, right. We’ve got him. Wow, these distress signals are through the roof. Did they want us to help him? Did they ask for a consult?” And the clinicians leaving the room now that his message has been delivered says, “No, no. They just wanted to make sure he was on our radar. They said they might call us next week.”

Eric: I love this one because that palliative care radar, I think is universal amongst palliative care teams. How did you think about this? Where was the inspiration for you?

Nathan: I guess I was thinking someone had recently come up and put somebody, quote, unquote, on my radar. And I was thinking what is this really? Because it’s not necessarily something that’s helping the patient, that bit of communication from them to me. And what I felt is it’s actually a transference of distress, meaning that the person who made that comment to you, that I want to put this person on your radar, is feeling a level of distress about that patient’s situation or suffering. And they’re wanting to share that.

Nathan: And so while there’s nothing therapeutic about it for the patient, they’ve transferred that distress. And now I’m thinking, well, what do I, as a palliative care doctor, do about that distress? Do I run? Do we put them on a list somewhere? And finding out that sort of situation is universal. Sometimes I really wish we could just go ahead and see that patient so that the distress could translate it into an intervention or into some sort of brainstorming or collaboration. I think it was just sort of commentary that I had running in my head about what is the real utility of this radar? And it turns out, everybody on social media commented that their institution was suspected of having such a radar, but did not have one.

Alex: I want to move to some of your longer form graphic art comics, and one that came out this week in the LA Times about advanced care planning. Let me share my screen here. I have so many windows open. This is one that you said earlier that you sometimes bring your work to people. And you actually reached out to me about this. And we’ve of course, discussed advanced care planning multiple times on this podcast with multiple different people. While I’m pulling this up, because I have so many of your comics open, I’m trying to find the right window, do you want to tell us a little bit about… Oh, here we go. I found it. Share. Do you want to tell us a little bit about your thoughts and what made you decide to do this? This is not a humorous one. We’ve talked about many humorous ones. This is very much in the vein of teaching, sharing your experiences, challenging experiences.

Nathan: Yeah. One of the things I think comics are really wonderful for is taking my own little niche of the medical world, this sort of small specialty of palliative care, caring for the aging, caring for those with serious illness and finding ways to translate what I’m seeing into something that a layperson can engage with. You guys have done some really wonderful discussions of advanced care planning, the nuance of what’s what. One of the things I’ve been thinking as I listen to this and read articles in the journals and editorials is I wonder what this conversation sounds like to the layperson. Are they saying, we just shouldn’t talk about it anymore. Is this really a futile effort, so to speak, in terms of dictating our wishes to those we love?

Nathan: And what I wanted to do is I guess, sort of twofold. One is encourage the general public to continue to engage with the idea of talking through our death and dying. Even if the process, perhaps isn’t as simple as we initially thought it might be 30 years ago, of just going to your lawyer, filling out the form. Maybe it hasn’t turned out to be that easy. And yet I don’t want people to throw that entire thing out. I still want those engagements. And the other thing I was hoping to sort of say to us as a field is we have come a long way in 30 years. And I’m so grateful for the pioneers who put in long hours and dedicated their careers to this research because I do think we’ve moved the needle. And I think that our culture has shifted in terms of our willingness to talk about death and dying. So that’s what I was trying to accomplish with this.

Alex: Yeah. I’m trying to think. Maybe we can’t read every panel, but do you want to walk us through the general story board here?

Nathan: Yeah. I share this story of a patient I cared for who was in the later stages of ALS and had lost much of physical function, lost voice. And I share how years before this patient and their family had prepared advanced directives. And yet, when the reality of breathing difficulties, BIPAP, the talks of tracheostomy and ventilators set in, what had seemed so clear on that piece of paper, no longer seemed so clear.

Nathan: And as I watched them wrestle in the hospital, it really drove home, this was years ago, it really drove home to me how different the idea of dying is from the reality of dying, and sort of having that physical loss and mourning and grief confront you is different from filling out a paper with a doctor or a lawyer. And yet, through all this, at the end of all these conversations, the patient ultimately decided to follow their previously stated wishes. And what I’m trying to argue is that neither the early conversations nor the late conversations were in vain. Those early conversations were part of charting a course that was winding and long. But they were still valuable. And the conversations that came at the end in the hospital, those were intense and heavy, but they were also still valuable.

Alex: And I do like the way where along the way, you honor, as you said, all of the work that’s been done by people within palliative care, people external to palliative care who have engaged in advanced care planning work. The growth of our field, dissemination of palliative care principles through books like Being Mortal by Atul Gawande, now a bestseller, honoring those in religious traditions who have contributed to thinking about our mortality. And then bringing it back to the patient, as you say, at the end. After days of discuss my patient decided to go home on hospice with her family, no tracheostomy, no respirator.

Alex: She ultimately chose the natural death at the house that she’d envisioned over a chance at more time on machines. The race they ran was rougher than they could have imagined when they signed the piece of the paperwork years before. But every conversation, from the first to the last, was a precious step toward the finish that was right for her. I really like this because I think it strikes the right balance about one, honoring the people who have developed this field. But also, the idea that just grappling with our own mortality has some intrinsic value in and of itself. And it may not directly lead to outcomes that are what the health system may desire in terms of direct correlation between health services use and advanced care planning completion. But they’re important steps. Each of these is an important step along the way. I wanted to ask you, this is LA Times?

Nathan: Yes, that’s correct.

Alex: And you published in Washington Post, Annals of Internal Medicine.

Nathan: Annals. Not Washington Post yet. I’ll work on them.

Alex: Okay. Next. And New York Times next?

Nathan: Annals, British Medical Journal, a few other, a publication called Topic that ran a piece about CPR. And yeah, and I’m always looking for new places to place my work, and again, try to reach new audiences. The LA Times has been a really well-trodden path over the last few years for me and I really enjoy working with the editorial team over there. It’s almost become sort of a puzzle for me because I have a set number of panels to work with. I have nine panels and I have to convey something as complex as advanced care planning through images and words. You can’t fit that many words on a page. If you haven’t already noticed, I tend to be a little verbose. And so the comics force me to confine my thoughts, to crystallize things into a small amount of space. And so with nine frames, I can take from, start to finish, and do that in a way that hopefully makes it into print and finds readers. And it’s a lot of fun, but a challenge.

Alex: Yep. Eric, you’re muted now. It’s not just me. [laughter]

Eric: You also have a website, right? The Ink Vessel?

Nathan: Yeah, I do. I use a mix of places to put my art, The Ink Vessel I post not probably as much as I should, but it’s a good place if someone’s looking for just sort of a smattering of work. And it’s also a great place, sometimes people reach out to me to ask about permissions for using cartoons. And as long as they’re not making any money off of it, I tend to be pretty liberal about granting. Since I’m not making a lot of money off of it, I tend to be pretty liberal about granting those permissions. But I just enjoy finding out where the work is you used. And so I’ve had people from around the world sort of email me, or message me via the website and ask to translate the cartoon into Portuguese or Spanish and use it for their own purpose. And I just think that’s wonderful. It really brings joy to my heart because this was never something that I imagine. I didn’t, as a kid, imagine being a palliative care comic artist. That’s most kids’ dream these days now.

Eric: Reading through your, your Twitter, what’s your Twitter handle again? It’s @NathanAGray?

Nathan: @NathanAGray. Yeah.

Eric: Which encourage all of our listeners to check out. Has a link to The Ink Vessel website on it too. But there’s also a hashtag for medicine, graphic artists.

Nathan: Yeah. Graphic medicine. And I’m grateful to be not alone. There were several really fantastic, I wasn’t by any means the first comic making doctor. And I’m really excited that there’s even more comic making doctors coming through. People on Instagram, people on Twitter. I could shout out like Shirlene Obuobi, she goes by Shirlywhirl, M.D. She has a book out. I could shout out Mike Natter. Grace Farris is at UT Austin now, and she makes comics about motherhood and medicine. She also has a book out, shout out those folks. But yeah, there’s a growing community of graphic medicine folks.

Eric: And do they use mainly that hashtag? What was it again?

Nathan: #graphicmedicine.

Eric: #graphicmedicine. And for, let’s say there’s a listener of ours who’s interested in doing this for themselves, you have a word of advice for them?

Nathan: Yeah. I think almost anybody can draw.

Eric: You haven’t met me yet.

Nathan: Well, so when you get past the idea of drawing to be realistic and you get into the idea of drawing to communicate an idea. There’s an old comic series online. I’m totally blanking. I think it’s XKCD. But it’s a statistician who makes comics with pretty much just stick figures. And they’re great comics. There’s a ton of emotion and you can convey ideas, sometimes even better with a sort of not very well drawn comic, than you can with a very realistic artistic looking single photo, or single photo realistic type of drawing. So drawing ability doesn’t always correlate with your ability to communicate an idea. I think you can draw, Eric.

Eric: I’m going to prove you wrong.

Nathan: So I encourage people to draw, to do it. When I go places and I talk to people about drawing, one of the things I try to help people do in the last few minutes is to actually make a little cartoon or something themselves. And it’s a lot to get adults to get past their inhibitions. Because when we’re kids, we all draw. Before we write down words, many others have made this point that we draw before we write verbally. And somewhere along the line, somebody comes by and tells us which ones of us can draw, which ones can’t. Somebody, Eric, went along and told you, you can’t draw and you stopped. And so now when you try to get adults to draw, it’s really anxiety provoking because somebody told them you’re inadequate on this. But it’s in some ways, a more primitive and more in tune with our emotions way of communicating, because you can scribble and convey anger that way, or just grab a giant crayon and put black crayon all over a page. And that can say a lot.

Alex: I wanted to say there’s, we probably don’t have time to do the whole thing, but you have another wonderful long form also published in the LA Times, comic about dying at home and how challenging that can be for caregivers. And I wanted to bring this up because I’ll just scroll through it as we’re talking. This comes from your experience with house calls for seriously ill patients after their hospital discharge. And you say I had no idea how much time I would spend wiping tears on the porch. And this caregiver saying, “I don’t know how much longer I can do this. He’s up every 20 minutes at night calling out. I’m giving him meds every hour. It’s just me here with him, day after day.” And one of the things that this comic does is that it’s somewhat subversive of the idea that the norm within palliative care, that a death at home is desirable and a death in the hospital is to be avoided. And I wanted to applaud you here because I do think that the best comics… Are they also called comics when they’re on the editorial page?

Nathan: I think they’ve taken to calling them graphic Op-Eds.

Alex: Graphic Op-Eds. The best of those are somewhat subversive. Right? They have an edge to them. And I think that this really challenges us, and while at the same time, ringing true. So I wondered if you, we’re running at a time, but if you wanted to comment on this particular comment or about that sort of line that you have to walk?

Nathan: Yeah. One of the most anxious parts of me for this process is when I finish the comic and all the final edits have been made, the comic is going to go live online for the LA Times. And I know it’ll get seen by a lot of people. The editorial team chooses the title. So this title was probably, I tend to be a little bit more nuanced in how I would frame things, but it probably doesn’t generate as many clicks. And the editors know how to get people drawn into that article. So probably not the title I would’ve chosen to capture all the nuance of what I was trying to say, but it did really get people talking, the title they chose of Think you want to die at home? You might want to think twice about that.

Nathan: Because I think what I was hoping to share is not that people shouldn’t go home to die, but that maybe we should rethink our value system for how we support various settings of care in our health system, that we’re dropping thousands of dollars a night in the hospital, and yet can only seem to offer a hospice agency a few hundred a day to take care of somebody who may have the exact same level of needs that they had a day before when they were in the hospital, but is now at home. And a lot of that work and effort has now been shifted onto a family who’s having to be doctors and nurses around the clock.

Alex: Yeah.

Nathan: So yeah, I was really a little anxious about how this one would go over, how it would land. The feedback was really tremendous. This, I think, was probably the most shared comic of all that I’ve done for the LA Times. And it was very cool on Twitter to get to watch everybody from, I saw a professional football player share this and talk about their experience with a family member. And I saw a famous sci-fi writer talk about her own experience with her mother at home. And seeing that this comic had sort of connected people and opened dialogue about yeah, we put up death at home as this ideal and yet the realities of it are really hard. It’s not a familiar territory for most people in modern society.

Alex: Yeah. Terrific. Well, because we’re running out of time, I’m going to leave it with the very last comic. Not that one. Oh no, did I lose it? I’m just going to describe it. I think it was a doctor describing early palliative care consults. You remember that one, Nathan?

Nathan: Yes.

Alex: On a Friday. Can you describe that one for me?

Nathan: This one, it was from several years back. And I think I had done a series for AAHPM Quarterly. And this one was in there and it’s become a perennial favorite. It gets shared about once a week, with there’s a grumpy looking doctor hunched over a chair, taking a consult phone call, returning a page. You can see the clock on the wall says it’s 4:30, or just after. And the quote at the bottom says, “Yes, early palliative care is better, like before it hits 4:30 on Friday afternoon!” I think there’s just that universal feeling of frustration when palliative care providers get a late in the day consult for a patient that probably needed us early that morning or even days sooner. Obviously, there’s no wrong time to involve palliative care, but there’s some times that are better than others.

Eric: Well Nathan, I recognize that it’s Friday and three o’clock year time, or four o’clock. Jesus. I want to thank you for joining us on this podcast. Before we end, maybe we get a little bit more Superman.

Alex: (singing)

Eric: Well, Nathan, very big thank you for joining us. I’ve been really wanting you to be on the podcast for a long time. I also wasn’t sure how was it going to work. Again, if you’re listening to this podcast, really encourage you to check out Nathan’s website, his LA Times articles, his Twitter page. If you want to watch us on YouTube too, I think you get a lot more out of it. But Nathan, a very big thank you for joining us on this podcast.

Nathan: Thank you. It was a joy. Thank you so much.

Eric: And thank you Archstone Foundation for your continued support, and to all of our listeners.