by Laura Petrillo (@lpetrillz)

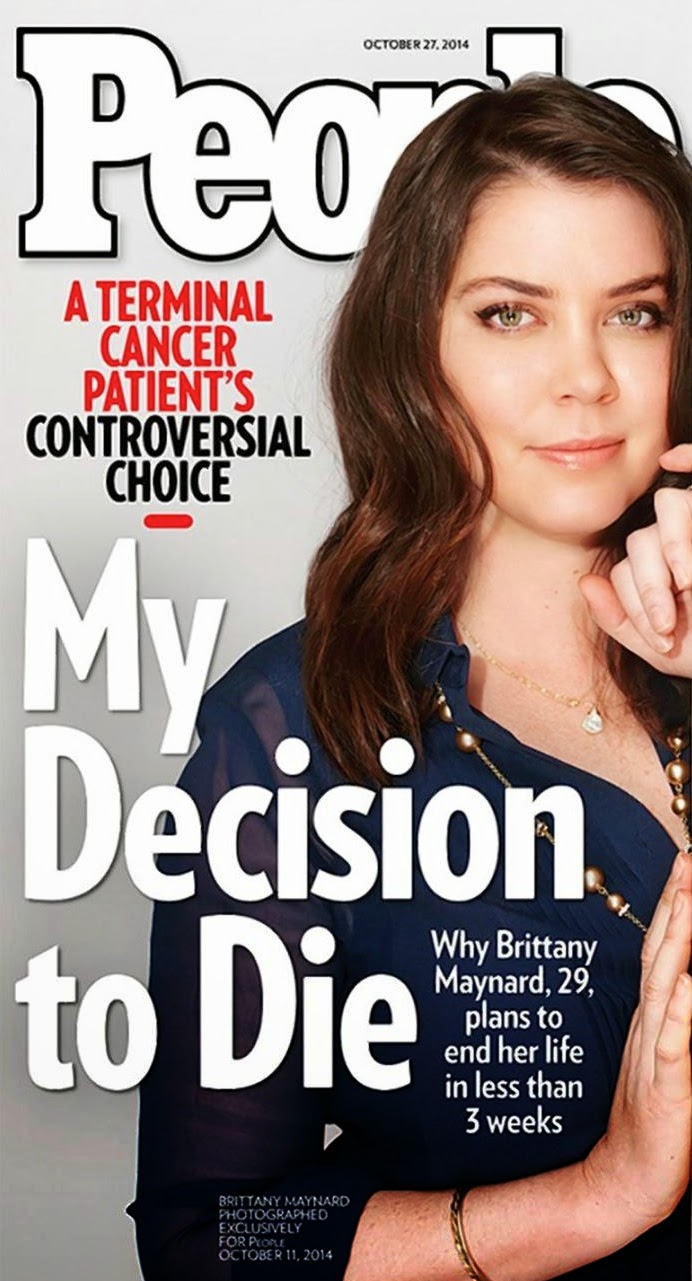

When Brittany Maynard announced her plans to end her life on November 1st, the news rippled through social and national media like the foreshocks of an earthquake. Ms. Maynard is a beautiful, relatable 29 year-old woman with a fatal brain tumor, who went public earlier this month with her decision to move to Oregon in order to obtain barbiturates via the Death with Dignity Act. She has partnered with the organization Compassion and Choices to create a campaign to advocate for increased access to aid in dying legislation. As bioethicist Arthur Caplan said on NBC News, “there are no new arguments in anything Brittany has to say,” and yet, she has captured the attention of a new generation, and sparked a conversation about the amount of control patients should have over their own deaths.

In this post I will not opine about whether patients should have access to physician aid in dying. But I will share my concern that like Brittany’s death, the timing of this conversation is simply too soon, and threatens to curb the groundswell of interest in palliative care and hospice that stands to benefit many more people than physician aid in dying ever will.

There is increasing appreciation that Americans don’t die well. Patients receive chemotherapy and intensive care up until the last weeks of their lives, rather than spending time with loved ones. They infrequently die at home, as most people would prefer to do, often because they seek aggressive care in hopes that extra treatments will give them more time. There are many factors that contribute to this avalanche of medical care at the end of life, among them the reluctance of physicians to discuss prognosis with patients and to plan for what to do if the third line chemotherapy for metastatic cancer does not go as hoped, as well as our cultural narrative about “fighting” illness, a narrative with no room for vulnerability, future planning, or asking for help.

In addition to the fear of honest conversation, there is a fear of inaction on the part of physicians. I noticed this firsthand this week when I was teaching ethics to medical students who were fresh off their first clinical rotations. One student struggled with the idea of withholding CPR from an elderly woman with a previous do-not-resuscitate order who suffered an unexpected cardiac arrest. The patient’s advance directive was not readily available, so the medical team attempted to resuscitate the patient until they were able to track down the physical advance directive and confirm her preference.

“It seemed so logical to give her CPR in that situation, since there was a chance of saving her life,” he said. “What were we supposed to do, just put her in a body bag?” He was not alone; other students told me about situations in which they wanted to encourage patients with poor prognoses to “be full code” with the assumption that this would give them more time with their families, or to offer patients procedures or treatments that might have any slight chance of increasing survival, even when there was a greater overall likelihood of harm. The students had only been practicing medicine for a few months, yet already felt an obligation to act in any way that prolonged life, no matter the risks or alternatives.

There is also increasing appreciation that we can do better by patients at the end of their lives. Dying patients who receive attention to their symptoms, as well as their psychosocial and spiritual needs in coping with advanced illness, not only rate that they have better quality of life, but actually live longer than patients who receive our current standard of care. A recent Institute of Medicine report recommended an increase in advance care planning, shared decision making and access to palliative care to improve care of the dying. Atul Gawande’s book Being Mortal has rocketed to the top of the bestseller list and generated an incredible amount of positive attention to palliative care and its promise in ameliorating the crisis state of end-of-life care in America.

The recent buzz about physician aid in dying jeopardizes that momentum, by steering the conversation toward the extreme rather than focusing on a solution for the broad middle ground. Patients and families are already wary of morphine, and suspect that it is used not only to palliate but also to hasten death. I suspect that if physicians were also given the power to prescribe barbiturates for aid in dying, that patients may fear that shifting gears from curative intent treatment to comfort-focused care at the end of life care might mean consenting to euthanasia, and shy away. And if conservatives erupted in “death panel” cries over physician reimbursement for advance care planning, imagine the backlash against aid-in-dying legislation. Even though they are distinct, opponents won’t hesitate to bundle these together and alienate patients from palliative care and hospice out of fear.

Moreover, I worry that physician aid in dying is yet another way to “do something,” rather than simply being present with patients through the uncomfortable, unseemly dying process. I was surprised to see an overwhelming amount of support in the comments responding to Brittany’s video, but on closer examination, many comments are simply anti-death: “Brittany, I salute you…. I have seen the most heinous of deaths and deaths prolonged because of guilt of the family, keeping people alive who are suffering” said one People.com commenter. A twitter post read: ” If a woman wants to die on her own terms & not suffer a horrendous death by cancer, let her.”

These posts present a false dichotomy of choices: suffer a horrendous death by illness, or choose death by fatal ingestion. This is not the case. In the vast majority of cases, hospice care can bring relief and comfort to patients and their loved ones, and facilitate peaceful dying without the need to resort to a pill to speed things along. Patients need to know that they will not be abandoned when treatments fail, and there are more ways to preserve dignity in the dying process. They also need to be free of any possibility of coercion– the greatest fear that most people have about the end of life is being a burden to their families. How terrible to contemplate patients choosing aid-in-dying to save money, or because they are out of options for compassionate home or residential hospice care, or worse, because they feel pressure to end the situation quickly.

We live in a society where we are never content to be still, or feel like there is a situation we can’t do something about. But when it comes to matters of death and dying, we owe it to ourselves to slow down. Talk with our patients and our own families about what is important. Learn what is making a dying person suffer, and either help her through it, or be present with her in her suffering. We need to ditch the fighter narrative, which empowers some but leads others down a fruitlessly aggressive path, and leaves them feeling stranded when the battle is lost. And as physicians, we need to let go of our need to be the hero, and recognize when to shift gears and help patients find the resources they need to feel comfortable and safe. Until everyone has access to comprehensive care, and information to make good choices about death and dying, it is too soon to talk about another “something” we can do to make the situation go away.