Our society is faced with the dilemma of aging prisoners, and some predict this will become one of the most important factors in managing the criminal justice system. Elderly inmates represent the fastest growing segment of federal and state prisons, a trend which is expected to continue. Hospice programs are growing in American correctional facilities, with access to health care professionals and efforts to provide a dignified death. In 2010 I took a road trip to photograph aging prisoners in one of America’s most notorious prisons, Louisiana State Penitentiary, also known as Angola Prison.

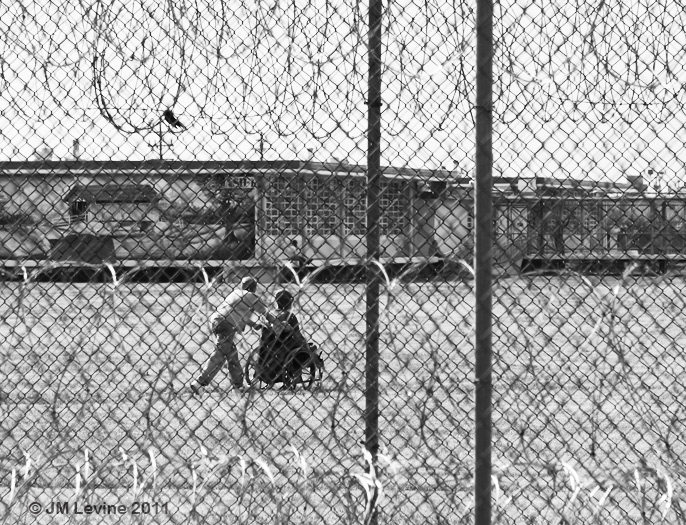

I heard about the penitentiary’s special programs for the elderly including a treatment center and hospice, and received permission from Warden Burl Cain to tour the facility with my camera. It was a 150 mile drive from New Orleans through Mississippi Delta wetlands to get to the place that was surrounded by razor-topped chain link fences and sentry towers. Before passing through the gates, armed guards searched my car and confiscated my maps. At 18,000 acres, the prison is the largest in the nation, housing over 5,000 inmates. It is roughly the size of Manhattan Island and surrounded by woods, swampland, and the Mississippi River. Nearly 74% of Angola’s prisoners are serving life without parole.

To accommodate its aging demographic, the Louisiana State Penitentiary implemented special programs to house and care for the frail and sick, and accommodate those who are dying. Inmates volunteer in the hospice unit, build coffins, and even provide burial services. The R. E. Barrow Treatment Center is the medical unit of the penitentiary, with an open ward of twenty-four beds which includes those assigned to hospice, plus special rooms reserved for prisoners who are dying. There are two LPNs and one RN available around the clock. When I visited, the census included prisoners with cancer, degenerative neurological illness such as ALS and stroke, and end-stage COPD.

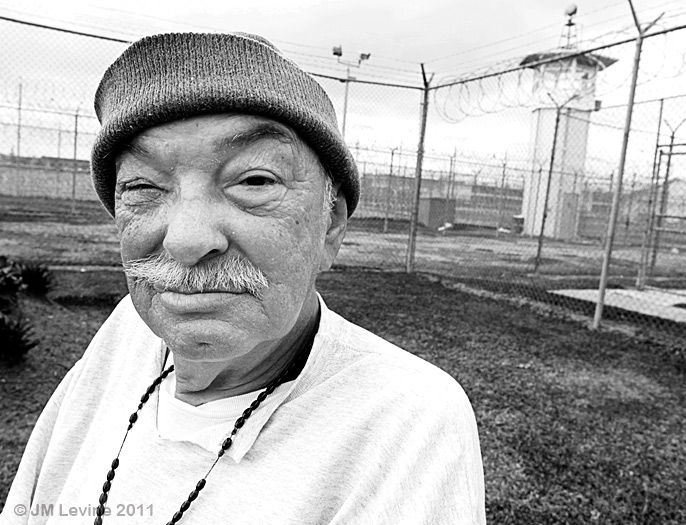

The Center maintains a volunteer program where inmates have the opportunity to feed and assist those who are dying or physically impaired. I spoke to Scotty, a volunteer serving two life sentences for double murder. He says the experience working with the aged and dying has humbled him and brought him closer to religion. I had a chat with an elderly inmate who couldn’t walk. He told me how in his youth he stabbed someone to death in a bar with a knife he kept in his boot.

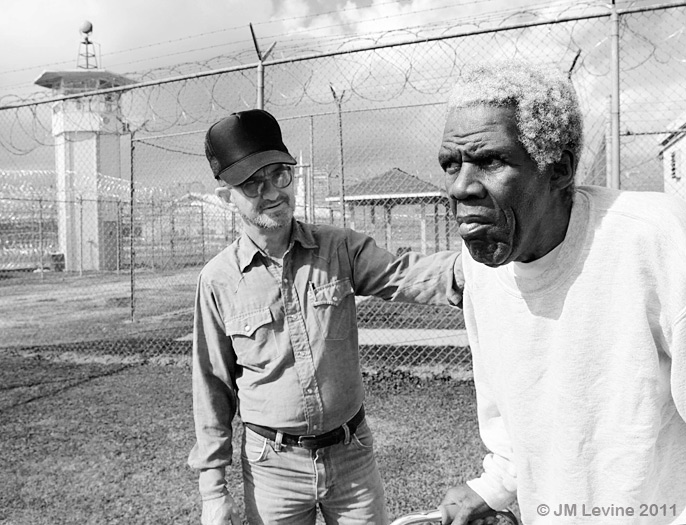

After visiting the Treatment Center we drove past fields with prisoners tending crops, with armed guards on horseback watching over the workers. My guide brought me to the unit which housed older and physically dependent prisoners. This unit had double bunks, with physically impaired prisoners and those needing adaptive devices assigned to lower beds. This is where I met Mr. Bourgeois, a ninety-two year old sex offender who was in for life plus thirty-five years, and the oldest prisoner in the penitentiary.

Mr. Bourgeois had a quick smile and seemed kindly and gentle, but a closer look revealed numerous scars etched on his scalp from fights during many years in prison. Mr. Bourgeois told me his biggest fear was being beaten up by younger inmates. The National Institute of Corrections has cited vulnerability of abuse and predation as one of the many challenges of a graying prisoner population, contributing to emotional stress and physical deterioration, and an observed phenomenon of accelerated aging.

Experts say that as a person ages they become less likely to commit crimes. Some criminologists refer to a “criminal menopause,” arguing for early release of older inmates citing potential cost-saving by allowing them to serve the remainder of their sentences in the community. However, the value of geriatric release programs must be weighed against public safety and costs related to other programs for their care. Because elderly criminals may be unable to care for themselves in the community, society would still be burdened by the cost of care even though they may no longer pose a threat.

Although he appeared frail, Mr. Bourgeois had surprising strength – perhaps nurtured by a life of crime and incarceration. As I left we shook hands, and I was startled as he nearly crushed my fingers, his face betraying a pleasured grin. As I looked into those eyes of stone I felt reassured that two very large uniformed officers were at my side.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Follow me on Instagram @jlevinemd

Dr. Jeff Levine’s photography exhibit entitled “An International Celebration of Aging” will be at the University of Michigan Medical Center from June to August, 2015 as part of their Gifts of Art program.

References for this post include:

Aday, RH. Aging Prisoners: Crisis in American Corrections. Praeger Publishers, 2003.

End of Life in Corrections

http://www.nhpco.org/sites/default/files/public/Access/Corrections/Corrections_The_Facts.pdf