|

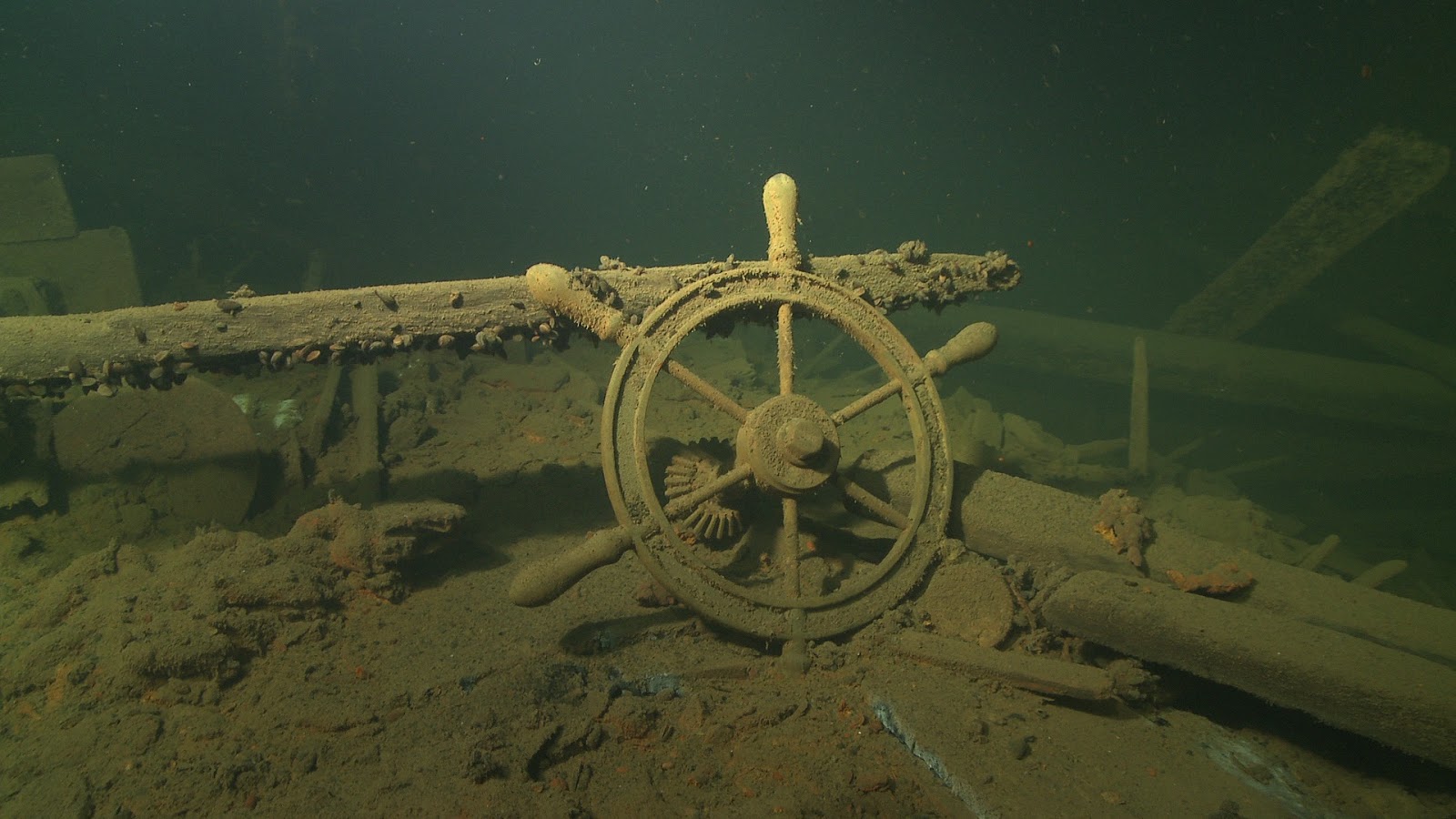

| AAPS objections to CMS payment for Advance Care Planning are a wreck. Source: Wikimedia Commons |

by: Stan Terman, PhD, MD

Beneficiaries of Medicare, and their families and surrogates, may soon have more opportunity to obtain an “explanation and discussion of advance directives such as standard forms” with physicians and other health care providers for one or more half-hour, face-to-face sessions. But first, CMS must review the approximately 240 comments that were submitted before September 8, 2015.

Several comments strongly objected to the proposal. Many objections seemed derived from the same boiler plate, but one by the Association of American Physicians and Surgeons (AAPS) is both strong and unique. This non-profit, 5000-member organization, which describes itself as “defending the patient-physician relationship and the practice of ethical medicine,” characterized payments to physicians as: “financial incentives,” “inducement,” “unethical conflict of interest,” similar to other “unethical bonuses,” and a “commission-like reward system.” It criticized the option for additional half-hour sessions as: “attempts to persuade patients or their families of something they would prefer not to do” which is “to forgo care near the end of their lives” and would subject Medicare beneficiaries to “unnecessary” and “repeated [and] extended badgering” that is “harassment.”

Payments of $87 to discuss a difficult, emotional issue for a half-hour are unlikely to be enough “inducement” for greedy physicians to practice unethically since primary care physicians generally earn over $300 per hour. Furthermore, AAPS’ objection is based on two incorrect premises. First, they asserted that the codes “would compensate a practitioner only if he obtains a completed form.” In fact, the proposed regulation refers to completing forms in this parenthetical phrase: “(with completion of such forms, when performed).” {Bold emphasis added.) Thus, payment is not contingent on completing forms, which makes sense since patients might not be ready to complete forms until their second or subsequent visit. This is consistent with the current emphasis on end-of-life planning as “having the conversation” being paramount, and this may suffice if it adequately informs treating physicians and proxies/agents.

AAPS’ second incorrect premise is that all end-of-life discussions must lead to forgoing life-prolonging care so that AAPS can then assert physicians “would be compensated for exploiting their position of trust to persuade patients to forgo care near the end of their lives”; payment is “an inducement for practitioners to talk patients out of medical care to which they are entitled”; and, “It is improper to pay a practitioner money to persuade a patient to waive his rights” that “could be used to his detriment later in order to deny care.” (This point of view could be considered a physician-individualized version of the “death panel” hypothesis.) AAPS concludes that CMS’ proposal provides “an unethical incentive” that will “drive a wedge between the patient and physician, creating distrust by the patient of his physician.”

Many organizations submitted comments in strong support of the CMS proposal, including Catholic Health Association and Trinity Health. Some comments provided excellent annotated summaries of evidence that Advance Care Planning benefits patient care and lowers the emotional toll of dying for caregivers and loved ones; for example, Rod Hochman (Providence Health & Services), and Catherine Dodd (San Francisco Health Service System).

Separate from this CMS-proposal-inspired debate were some brief comments of Ezekiel Emanuel (physician and medical ethicist, U. Penn.) and Thomas Smith (oncologist and director of palliative care, Johns Hopkins), who participated in a recent Freakonomics podcast:

Dr. Emanuel said, “Talking about the end-of-life is the hardest thing a doctor does. And it’s emotionally charged; it’s physically draining; it takes time. And we need to recognize that increasingly these kinds of conversations… they require a lot of skill, as much skill as maybe doing a colonoscopy or doing a surgical procedure. It’s not physical, manual skill, it’s not about dexterity, but it is about something probably just as important if not more important. It’s about emotional understanding of patients and it ought to be compensated the way we compensate for other skills and talents.”

Dr. Smith said, “None of that [CMS proposal] is trying to get people not to be coded [to opt for DNR], not to be in the hospital… but just to discern their wishes. We can’t honor people’s wishes unless we know what they are… about resuscitation, being on a ventilator, being on dialysis.”

While no patient is required to make an appointment to discuss Advance Care Planning and while those who do are not required to forgo life-sustaining treatments, physicians must discuss possible end-of-life conditions with their patients so they can learn about their patient’s life values and goals of treatment. Patients need information and then time to think about and discuss these issues. It’s hard to imagine this could be accomplished in fewer than two half-hour sessions. After patients decide what specific treatments they do, or do not want for particular end-of-life conditions, they can complete forms that include: Living Wills to memorialize their expressed personal wishes; Durable Powers of Attorney for Healthcare Decisions to legally designate their selected surrogate decision-makers; and POLST paradigm forms they must cosign after they are sure this set of actionable medical orders authentically reflects their treatment goals.

Some religious authorities do discourage Living Wills. Examples: Father Tadeusz Pacholczyk’s essay answered “No” to his article’s title, “Should a Catholic have a ‘Living Will?’” The Catholic Bishops of Wisconsin published a strong warning that explained why followers should not complete POLST forms. Yet the 1990 Federal Patient Self-Determination Act states, “Health care providers are not allowed to discriminately admit or treat patients based on whether or not they have an advance health care directive.”

In fact, completing Advance Care Planning forms can either forgo or request care. Nothing in the proposed CMS regulation requires patients to choose, or physicians to influence them to choose, forgoing potentially life-sustaining treatments. Instead, these sessions may result in completing forms that indicate the patient’s preference is to continue life-prolonging treatment indefinitely. Most forms are balanced, but many are unfortunately vague. Example: the Uniform Health-Care Decisions Act’s Advance Directive (which has modeled many states’ official forms) provides two check boxes. One is: “(b) Choice To Prolong Life” that continues, “ I want my life to be prolonged as long as possible within the limits of generally accepted health-care standards.” Similarly, all POLST paradigm forms have check boxes to select “Full Treatment.” If a practitioner did present an unbalanced form to patients, their family members, surrogates, or advisors, they could decide that the form did not match their values or treatment goals and refuse to sign. In addition to this right to veto a proposed form, the author is aware of two pro-active approaches that are discussed next.

As part of its “Will to Live Project,” the Robert Powell Center for Medical Ethics offers “a legally binding pro-life alternative to traditional Living Wills” for those who want to prolong their lives, regardless of its condition. The center’s website strongly advises patients to avoid vague language since it could let others misinterpret their wishes and result in withdrawing or withholding of life-sustaining treatments. Another instrument, the Natural Dying—Living Will, can be used as a “will-to-live” and it strives to be specific in describing conditions and interventions. While the Powell Center has not recommended this form, this is not surprising since most who complete it want to avoid the suffering and prolonged dying of terminal illnesses, especially advanced dementia.

The “Natural Dying—Living Will” is generated by making “one decision at a time” using a decision aid tool that describes and illustrates 48 common end-of-life and advanced dementia conditions. For each condition, patients can decide “Treat & Feed” for every condition—if they want to live as long as possible can. (Note: Usually, patients decide on “Natural Dying” for some conditions, based on their previously judging that the continuation of life-sustaining interventions would cause them more harm and burdens than benefits.) Patients can even make their decisions irrevocable.

Rather than using “Medicare payments to drive a wedge between the patient and physician…and failing to improve medical care in any way” (as AAPS claimed), the CMS proposal would provide patients opportunities to discuss with physicians or practitioners, their life values, including religious values and goals of treatment. Learn their patients’ wishes is a prerequisite to physicians’ honoring them. While AAPS warns, “Healthy patients years away from the end of their lives may change their minds before ever confronting an end-of-life scenario,” no problem results from making treatment decisions before patients enter their final declining stage of health. Patients may have accidents or unexpected medical events such as strokes at any age, and then their completed forms can provide guidance for treatment decisions. What is important to appreciate is that patients can always change their minds—as long as they still possess capacity.

People’s greatest end-of-life fear is to lose control over their destiny. Why is this fear realistic? Because if others are in control, these others can decide how long and how much a patient will be forced to suffer before he or she dies. Some people also fear financial pressures may lead to treatment decisions that will force them to die prematurely. Fortunately, it is possible to maintain control in both directions by diligently selecting and completing Advance Care Planning instruments. Some do-it-yourselfers download internet forms. Many people sign standard forms that their attorneys attach to estate planning documents. Yet clinicians are in the best position to know what end-of-life trenches are really like. It is significant that a prominent attorney organization, the National Academy of Elder Law Attorneys, implicitly endorsed this view by strongly supporting the CMS proposal and by citing the Institute of Medicine’s Dying in America report that noted physician “time constraints and distractions” were the core obstacles to effective clinician-patient communication needed for advance care planning. Why? Because this prestigious organization did not add, “attorney-client communication.”

Regarding planning for the last chapter of life for patients who are in reasonably good health, the best way is to discuss their options with their primary physician. For seriously ill patients who have life-threatening illnesses, the best way may be to discuss their options with their treating specialist physicians. Of course, all patients need to be informed about palliative care. These discussions can increase mutual trust if all agree the goal is to attain a peaceful and timely dying. In contrast, the comments of AAPS and others—who denounced all discussions about end-of-life options as agenda-driven acts of coercion by greedy physicians—are appalling. The new CMS codes can help foster discussions that can lead to empowering acts of planning that ultimately make it possible for the last chapter of a person’s life to be harmonious with his or lifelong narrative.

Stanley A. Terman, Ph.D., M.D., is a psychiatrist and bioethicist who leads Caring Advocates, a non-profit organization that offers the Natural Dying—Living Will to help complete effective Advance Care Planning for Advanced Dementia and other terminal illnesses. He thanks Karl E. Steinberg, M.D., C.M.D., for his comments and suggestions.

Sources

See Federal Register, vol. 80, no. 135 (July 15, 2015), at 41773 (CMS-1631-P) re: CPT codes 99497 and 99498. (c) Advance Care Planning Services, p. 41773. Available: [http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2015-07-15/html/2015-16875.htm]. Accessed 15 Sept 2015

Federal Register Medicare Program; Revisions to Payment Policies Under the Physician Fee Schedule, Clinical Laboratory Fee Schedule, Access to Identifiable Data for the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation Models & Other Revisions to Part B for CY 2015, i(26).

Available: [https://www.federalregister.gov/articles/2014/11/13/2014-26183/medicare-program-revisions-to-payment-policies-under-the-physician-fee-schedule-clinical-laboratory#h-200]. Accessed 15 Sept 2015.

Freakonomics Radio: Are You Ready for a Glorious Sunset? August 27, 2015. Audio available: [http://tunein.com/topic/?TopicId=100737155]; Transcript available: [http://freakonomics.com/2015/08/27/are-you-ready-for-a-glorious-sunset-full-transcript/]. Accessed 15 Sept 2015.

Father Tadeusz Pacholczyk: Should a Catholic have a “Living Will”? 2007. Available: [http://www.catholicnewsagency.com/resources/life-and-family/euthanasia-and-assisted-suicide/should-a-catholic-have-a-living-will/ ]. Accessed 15 Sept 2015.

Catholic Bishops of Wisconsin, Upholding the Dignity of Human Life: A Pastoral Statement on Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (POLST) from the Catholic Bishops of Wisconsin (2012). Available: [http://www.wisconsincatholic.org/WCC%20Upholding%20Dignity%20POLST%20Statement%20FINAL%207-23.pdf]. Accessed 15 Sept 2015.

Patient Self-Determination Act, Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1990, Public Law No. 101-508 §§ 4206, 4751, codified at 42 U.S.C. §§ 1395cc.(a)(1)(Q), 1395cc.(f), 1395mm(c)(8) and 42 U.S.C. §§ 1396a(a)(57), 1396a(a)(58), 1396a(w) (1991)

UNIFORM HEALTH-CARE DECISIONS ACT 1993 “(6) END-OF-LIFE DECISIONS: (b) Choice To Prolong Life: I want my life to be prolonged as long as possible within the limits of generally accepted health-care standards.” Available: [http://www.uniformlaws.org/shared/docs/health%20care%20decisions/uhcda_final_93.pdf]. Access 15 Sept 2015.

Robert Powell Center for Medical Ethics: Will to Live Project. Available: [http://www.nrlc.org/medethics/willtolive/]. Accessed 15 Sept 2015.

The Caring Advocates Natural Dying—Living Will. Available: [http://www.caringadvocates.org/card-sorting.php]. Accessed 15 Sept 2015.