#ThisIsOurLane. While I guess that hashtag could make you think we are going to be talking about dementia and driving, it really is a reference to a recent viral discussion on twitter about firearm safety. It began with the NRA’s tweet in response to the American College of Physicians’ position paper on reducing firearm injuries and death, which said: “Someone should tell self-important anti-gun doctors to stay in their lane.”

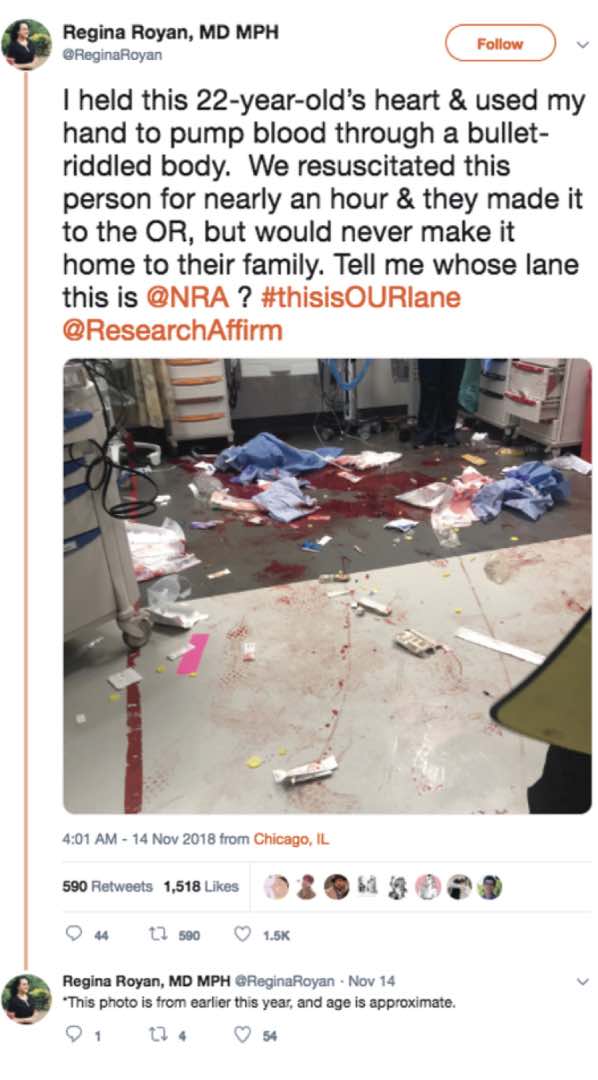

This tweet was met by a pretty immediate online reaction by many members of the medical community using the hashtags #ThisIsMyLane and #ThisIsOurLane. The responses frequently included graphic depictions of the aftermath of firearm violence.

Well, on today’s Podcast we talk with Marian (Emmy) Betz, one of the authors of a recent NEJM piece on #ThisIsOurLane and an expert on the topic of dementia and guns. Emmy is an Associate Professor in the Department of Emergency Medicine at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, and has written some pretty amazing papers on the subject of firearm safety, including these:

- #ThisIsOurLane — Firearm Safety as Health Care’s Highway. NEJM 2018

- Firearms and Dementia: Clinical Consideration. Ann Intern Med. 2018

- Firearms and Suicide: Finding the Right Words.Betz ME.Acad Emerg Med

Also, check out her great TED talk on “How to talk about guns and suicide”

Eric: Welcome to the GeriPal Podcast! This is Eric Widera.

Alex: This is Alex Smith.

Eric: Alex, who is our guest today?

Alex: Today we have a super star researcher, Emmy Betz, who’s an emergency physician and researcher at the University of Colorado. Welcome to the GeriPal Podcast Emmy.

Emmy: Oh I’m so honored to be here, especially as a non geriatrician, non palliative care person.

Eric: We have a great topic today, all about guns and dementia, and a whole other discussion on that, including whether or not this is our lane to stay in. But before we do that, I saw you want-

Alex: Jumping at the gun, want to get in there. Jumping the gun.

Eric: There’s gonna be a lot of puns in this podcast. I’ll just start off with a song request though before we go into the puns. Do you have one for Alex?

Emmy: I do. I originally was thinking of a Reggae song, I Shot the Sheriff, but I know you don’t like Reggae, so instead I went for an old cowboy hit by Johnny Cash, Don’t Take Your Guns to Town.

Alex: Hey, I have nothing against Reggae. I could’ve done Reggae. But I do love Johnny Cash.

Emmy: I thought you said you don’t do Reggae?

Alex: Reggae’s fine, Reggae’s fine. [Singing]

Eric: We’ll have more of that at the end. We usually ask people, “Why did you choose this song?” But it seems quite appropriate. I get it why we chose that one for …

Emmy: Well, I will say though, in particular, you’ll notice the mom is not saying, “Don’t own guns,” she’s saying, “Just don’t take them with you.” I think that is a nice way of actually framing what we’re gonna talk about today, that this is not about ownership or gun rights, this is about safety and not getting shot.

Eric: Okay. What are we talking about today? Why don’t we start off with a big event I would say that blew up in social media, is this … What’s the hashtag?

Alex: #thisisourlane.

Eric: #thisisourlane.

Alex: Yeah. Emmy do you wanna set this up for folks? How did this happen?

Eric: Is this about carpooling on the freeway?

Emmy: Yes, I once … It was on, I think it was early November. The Annals Internal Medicine published a new position paper from the American College of Physicians about firearm safety. In response, the NRA tweeted out this tweet about how, I believe the words were, “Self-important physicians should stay in their lane, and shouldn’t be talking about firearms.”

Eric: Yeah, self-important anti-gun doctors to stay in their lane.

Emmy: And how we hadn’t consulted anybody in that. I’ll say, I had nothing to do with the recommendations and etc. What happened, I think afterwards, was really pretty remarkable. There was this particularly Twitter movement of all the med Twitter people. I think it felt particularly offensive that someone was telling doctors what we should and shouldn’t weigh in on, especially when it’s a health and safety topic.

I think it happened to come at a time when there’s been this growing movement and engagement by physicians about the importance of looking at firearm injuries as a health problem. I think these things crashed at the same time. A lot of people were tweeting out somewhat gruesome photos of what they see in their critical realm, bloody scrubs and things. About how it impacts us as providers too. It’s been pretty remarkable to see what’s happened with it.

Alex: You had a New England journal perspective about this piece. You were one of the authors on this piece, and it actually has the images of the phones with some of the tweets. I’m sure many of our listeners who tend to be social media savvy are probably familiar with some of these Twitter images.

Eric: For those who are not, we will have a link to this New England journal article on our podcast, as well as the other articles we’ll be talking about today.

Alex: In geriatrics and palliative care, but do we ever encounter guns in geriatrics and palliative care, or is this part of our lane too? Do we have these gruesome photos?

Eric: It’s just that emergency medicine thing right?

Emmy: I mean, maybe. What we actually tried to say in the New England journal piece was really that, this is not … The gruesome photos are trauma and emergency medicine, but it’s not just physicians, and it’s not just the frontline groups, it’s all the people who take care of patients rehabbing after an injury. Then really importantly, also all kinds of people in the primary care space, including geriatrics and palliative care, we think about people who are at risk of firearm injuries and deaths, and how we can help prevent them. The biggest one, especially in the older adult population, separate from dementia, is gonna be suicide. Especially older white men have really high suicide rates from firearms. Absolutely it’s your lane, you should totally come on in, we’re all in this together. Hopefully today we can talk about what that means.

Eric: Can I ask about the suicide and the older white men? I quickly looked up suicide rates, and it looks like for suicide, actual suicide rates, it actually looks like it’s pretty steady when you’re older, except for this older white men population. Where you look at the rates with every decade, it just keeps on increasing and increasing and increasing. Is that right? Did I read that right?

Emmy: Yeah. It’s interesting. I think we often, at least in emergency medicine, think of suicide as the problem of young, college-aged girls. The overdoses that we see, and that people recover from. But the real trends are that, yeah, it’s middle aged and older, especially white men increasing. A lot of that is because they’re more likely to use firearms. For any given attempt, a firearm is about 85/90 percent likely to result in death, because guns are lethal, that’s what they’re supposed to be, compared to medications or other methods. When those men in particular tend to reach for a gun, they’re more likely to die. That’s why the death rates are really high. They actually don’t even make it to the ER usually, because usually they die at home.

Alex: They die at home.

Eric: Is it true to say that suicide attempts are probably about the same amongst different people, it’s just the lethality of the attempt is different depending on …

Emmy: Yes.

Eric: Yeah?

Emmy: Actually though, we know, I’m gonna get in trouble if I quote this wrong, because some listener will check it, but I think when you look at the attempt to death ratio, in older adults it’s something like, four attempts per suicide death. In younger people, it’s like 20 to one. That has to do with the fatality of it. Older adults are much more likely to use these highly lethal methods. There might actually be a higher attempt rates in younger people, but they thankfully tend to survive.

Alex: I saw your Tedx Talk about suicide. Terrific, in 2015, wonderful. People have a link to that as well. There was this story there about impulsivity as well, and that so often these are impulsive acts, and yet for older adults who are using firearms, and white men who are most commonly using them, the death rate is so high, so there’s no chance to recover from that impulse and think things through again.

Emmy: Right. It doesn’t mean it’s impulsive in the sense that somebody’s walking along and suddenly he’s like, “Oh, I think I’ll kill myself today.” Not that kind of impulse. Impulsivity in the sense that, someone may have been struggling for a while, but the time from deciding to take action to taking action can be really short. It’s like this window of risk that we often talk about as impulsivity, but it’s about putting time and space between somebody who’s at risk and dangerous. It’s a lot like the designated driver kind of analogy of, don’t get behind the wheel when you’re intoxicated. It’s the same thing if you’re at risk of suicide, you shouldn’t have access to guns.

Alex: Right.

Eric: Go ahead Alex.

Alex: Maybe we should transition to talking about the main topic of today, which is dementia and guns. I wonder if you could tell us a little bit about what got you interested in this particular angle?

Emmy: Yeah. I will say, we’ve been working on this now for over a year. This predated the, #thisisourlane stuff. I do a lot of work related to driving and driving retirement in older people, and how people make those decisions.

Alex: That’s an easy problem to solve by the way isn’t?

Emmy: Yeah. I totally think that. Yep. Oh wait, no.

Alex: After you fixed that you thought, “What am I gonna do next?”

Eric: Guns. That seems easy.

Alex: Dementia and guns.

Emmy: Well actually I went from driving to suicide and guns, and then I was like, I’m just gonna throw dementia in there too. Let’s just shake it all up. Somebody once said to me that my work is about difficult conversations, which it kind of is actually. There are really interesting similarities between conversations about, is it time to hang up the car keys, and what do you do with somebody’s firearms? They could both be really linked to somebody’s sense of self, and independence and all of that. But they’re also potentially safety issues.

Alex: Clinically, has this come up in your practice in emergency medicine or for your colleagues?

Emmy: Yeah. It has come up at least once for me. I had an older man how had dementia and was brought in from home by family for sort of, not safe at home globally anymore. We talked about it, they had actually already locked up his firearms. What I have heard from lots of people in the outpatient space, is that this comes up all the time in dementia care clinics, especially at the VA.

Eric: Yeah. The stories I hear the most are actually the people who go into people’s homes, including home base primary care. This is a big topic.

Alex: Right. We were just interviewing a physical therapist, who happens to be from Colorado, today for our research program. He’s doing a PhD at the University of Colorado. He said, “Oh yeah, at our VA, going to do therapy in people’s homes, and there’s the gun right there. You’re sit next to him while he’s talking to the person.” Do we have some empirical data about how common gun ownership is among people with dementia?

Emmy: Yes and no. I will put in a plug for any of your listeners who have any data or are interested. Please get in touch, because we would love to know more of what’s happening in different places around the country. Overall, when we look at older adults separate from dementia, we estimate that about 50% of people live in a home with a gun. That’s because about third of older adults own a gun, and another 12% don’t own one, but live in a home with one. Roughly 50%. There was a study in 1999 in the dementia clinic where 60% of the patients had access to a gun at home. Then there was a 2015 study in a different clinic where it was like 18%. Somewhere between zero and 100% of … It’s really hard to know. I think we definitely know it’s a real thing that people are facing. We need more numbers for sure.

Alex: Right.

Eric: Well it’s interesting to know whether or not, ’cause I thought they do the home base primary care teams, they actually ask on intake about gun ownership. They got all those different diagnoses including dementia they screen for. Maybe an import in population. I think hospice agencies-

Alex: Do they?

Eric: I think. I’m not sure, but I’m pretty sure HBPC does.

Alex: Or ought they?

Eric: Yeah, they probably ought.

Alex: Well we’re kind of getting into recommendations, what ought they do. But maybe we’ll stick with … We’ll talk about how common this is or might be, but why is it important? Maybe we’ll go there next.

Emmy: Yeah. Good question. When we look at overall firearm deaths among older people, something like 90% are suicides. Still the bulk of deaths, including people with dementia, are gonna be suicide. Certainly we think dementia itself can be a risk factor for suicide, especially in the earlier phases. The thing that I think we all worry about as healthcare providers ourselves and as people wanting support caregivers, is the risk of violence to others. That is really hard to get numbers on.

Emmy: How often does a visiting healthcare provider have a potentially dangerous situation? I’ve heard lots of anecdotes about family members in the middle of the night when the person doesn’t recognize them and thinks … But there’s no injury, so those don’t get counted. Then sadly there are definitely anecdotes out there where the person with dementia didn’t recognize the wife, shoots the wife and then shoots himself. It’s just really hard to get estimates of how often those are happening.

Eric: Yeah it’s fascinating. I was reading the New York Times article on dementia and guns, which you were cited on, and just reading through some of the comments. Some of the people said, “This is not a problem. How often do we actually hear about an older person shooting up a Kindergarten class,” or something. I don’t remember what the analogy was, but it was that. I thought, “Man, if the bar has to be mass shootings, that’s a high bar.” Secondly, just the fact that these older adults with dementia, it sounds like 9 out of 10 of them are committing suicide. Not 9 out of 10 older adults with dementia. But, when there is-

Alex: An attempt.

Eric: An attempt. Or, when somebody does-

Emmy: No, of gun deaths.

Eric: Of gun deaths.

Emmy: Most of them.

Eric: Most are suicide from guns. It’s just absolutely fascinating. It’s not a homicide issue. The biggest issue is a suicide issue.

Emmy: Well I do think too, when you think about the general public, like the New York Times stuff, for people who don’t know anyone with dementia or who don’t own firearms, I think they’re like, “Why are you talking about this? This is not a big deal.” But when you talk to people who work in the dementia space or who have a loved one and have firearms, this is an emotionally very difficult decision, I think. That’s whey we’re focusing on it.

Alex: Right. Guns and dementia, it is an issue. Is there some push back here? If I have dementia, I wanna be able to take matters in my own hands and end my life. That means I should have a gun available to me, because that’s the best way to end my life.

Eric: That was actually, I think, the first comment I read on that New York Times article is, “We have no other helpful means to end our lives. Unless something happens, this is one of them.”

Alex: Right. There is this argument out there. What do you make of this argument, Emmy?

Emmy: Oh, it’s such a tough one, right? I think this is where you start blurring into this philosophies about end of life and death with dignity. If you have some kind of terminal illness and whether suicide is right or wrong. I am not the one to solve that problem today.

Eric: That’s the next step for you.

Emmy: That’s the next step when I get bored with this, yeah. I mean, I think the way I look at it is, in younger populations, we argue, I think we should argue this in older adults generally too, we argue that being suicidal is not normal in that, we should do everything we can to try to help that person overcome those feelings. But if it’s related to pain or social stressors or untreated depression and so forth, that we that’s why we have a lot of things in place right as providers, we can hold people in the hospital against their will and so forth. There’s some separate data showing the depression is under identified and undertreated in older adults. I think it’s important we avoid this ageism of, “Well, so and so is older and maybe has dementia, of course he’d want to kill himself.” But I also understand the nuances of, especially for somebody who has always been very in control of their life, them wanting to have that option.

Eric: Yeah, I can imagine if it’s an issue of impulsivity in somebody who’s actually becoming more impulsive because of their dementia. There’s got to be things that we can do that actually help with that. I think the other thing is not just coming from the patient centered focus, but everybody who has to deal with the aftermath of a suicide, and especially a suicide by a firearm, that’s hard.

Alex: Right.

Emmy: Yeah.

Alex: Yeah, I wonder if there’ve been studies of post-traumatic stress or complicated grief following a suicide from a firearm versus other means.

Emmy: I don’t know that, I do know there’s a lot for the surviving friends and family after a suicide. It’s definitely often different than the typical grieving process. I think that’s when I think about what we’re gonna recommend in this dementia and firearms space, a lot of it is bringing up the topic, and then in some ways turning it back to family, so they’re at least educated of the risks, aware, and can make family decisions. They may say, “Look, we think dad is … He’s always said he would never go in a nursing home. This might be the way he’s gonna go.” But I think you want them to at least be thinking about all these things so that they’re informed. Hopefully they make the home safer. But at the end of the day, we can’t control what people do in their private homes.

Eric: Well let’s talk a little bit more about that. What can we do? It sounds like the very first thing is, start the discussion.

Alex: We have to ask.

Eric: We have to ask. What does the ask look like? Do you have guns at home? Or is there something else that we should say?

Emmy: Yeah, good question. The VA has this template checklist. I think that many places are using as part of an initial dementia diagnosis. The Alzheimer association also has some materials online for families, but then really thinking about the firearm issue. I think it really makes sense to put it in context of other safety risks. If you’re talking about the home environment, you talk about access to power tools, and are they in the kitchen by themselves, are there firearms in the home?

It becomes the whole environment, and driving as well. Are they still driving? Do they have access? You can start by asking something like, “Are there guns in the home?” If they say yes, you might say, “Well, does the person have access to them?” Because it may be there are guns, but they’re locked up securely. In that case you don’t have to worry as much about the person with dementia.

Alex: If they’re not locked up securely?

Emmy: Then you would want to talk about the options. I will pause here to say, I do not think physicians and healthcare providers need to be experts on this. There are some resources if you wanna learn more. It’s good to not sound like a total idiot. To know the basics that they’re are actually a lot of different options for people, and know where to send them. Having said that, there’s three main approaches. One is to lock them up. That can be a lock box, a safe, those trigger locks and cable locks you see, they’re like bicycle locks. They sometimes aren’t quite as safe. Lots of different locking devices.

You can also try to make the gun less lethal. Take out the ammunition, put the ammunition somewhere else. If you know how to do this, you can take the firing pin out, in which case the gun looks normal but can’t shoot. Then the third main option would be, to get them out of the house. Store them off site, give them to law enforcement if you don’t want them anymore, transfer them to a different family member. It kind of depends. If the person with dementia is living at home with an adult son who wants to have their firearms still, they might choose one thing. If the person with dementia’s gonna be really anxious if they can’t touch their gun every day, then you might think about disabling it. They can’t really tell it’s disabled, but it’s safer.

Alex: What’s the next step? Is there a role for education there about the risks of dementia and guns?

Emmy: With family you mean?

Alex: Yeah with family.

Emmy: Of for sure. Sorry. Yeah. As part of that conversation, I think it would be explaining what the various risks are. We’ve talked about suicide a bit already. I think that in talking about the potential risks to others. This is where I think it can be hard, because most people don’t want to think that their loved one could hurt somebody else, right? You can imagine dad’s always been really safe around his guns, he would never hurt any of us. I’ve heard one woman, Julia Sussman, she works a the VA in the dementia clinic, she sometime explains, “It’s not your father doing this, it’s the disease doing this,” and explaining the paranoia and aggression, and difficulty recognizing people. It’s those sorts of things that can happen that can be a risk.

Alex: Yeah.

Eric: One of the things we face a lot is, we see older adults with dementia who may be living home alone and isolated, may not have family, maybe estranged from family. What do I do if I’m actually worried about this person? I’m worried about their guns at home. I feel unsafe when I do a visit. Are there legal mechanisms to actually maybe take away the guns or to what happens then?

Emmy: Yeah, great question. Currently, a number of states have what are called Extreme Risk Protection Orders, or Gun Violence Restraining Orders. It depends where you live. If you live in a state that has one of those, then either family members or law enforcement can remove guns from somebody who is at risk of harm to themselves or others. There’s a whole process and it’s temporary, and you have to go before a judge, etc. I think only Maryland allows healthcare providers to actually request the removal. But I would imagine in that situation, that you could potentially involve police to express your concerns, and then police could get involved.

Otherwise, for example, in Colorado we don’t have one of those. There are fewer options for sure. I think it depends on the person’s capacity and whether you feel like the global capacity of being able to live by themselves and make decisions and so forth, still. I will say too that, there are only two states that have specific firearm laws related to dementia. Hawaii prohibits possession by people with organic brain syndromes, which could include dementia. In Texas, you can possess a gun but you can’t get a permit to carry it in public. There are no other specific firearm laws right now, at least at the time that we did the analysis. About late 2017.

Alex: It’s really interesting, the parallels here with driving. I remember you were on an NPR segment with Melissa Block, who as I understand it, flew out to Colorado and you took her to a shooting range, right?

Emmy: Mm-hmm (affirmative). Yeah.

Alex: My favorite quote from that piece, I believe it was form that piece, is, “Why would we take away somebody’s drivers license, and yet still allow them to own a gun?” Or something along those lines. In terms of public health, the gun safety issue is lagging far behind the driving safety issue.

Eric: It’s ’cause the constitution doesn’t talk about driving automobiles.

Alex: Maybe that’s it. Right. Interesting in your thoughts there, the parallels with driving. Should we have more of a public health sense that drives laws restricting, or maybe allowing for a greater role for physicians to have some power to remove guns from people who are unsafe?

Emmy: That’s a good question. In some ways, I actually am okay with physicians not being the ones who generally can report, because of the importance of the physician/patient relationship, and that often there are still mechanisms or ways we get other people involved. I think absolutely, we need a public health approach to the whole issue of firearm violence. When I say public health approach, some people now think that’s code word for gun control. It’s really not. I’m a public health junkie. You need to look at all angles.

Sure there might be policies and legislative approaches, but that’s only once piece of it. What about education? For example, gun safety courses right now don’t talk about suicide risk or what to do if your buddy’s having a rough month. Maybe they should, and maybe they should talk about advance planning for if you develop dementia or another reason when you’re no longer safe. What are the educational approaches that actually effect home storage behavior? Then engineering is important too, right?

We make cars safer. Are there things we can do in terms of firearms themselves or locking devices that we can use our technology approaches to help fix? I do think we need a broad approach. I do think it’s different from driving because of the second amendment. But that’s where I think again, hopefully a lot of people are gonna have friends, families involved. How do we engage the firearm owning community in this, I think is gonna be critical.

Eric: I got two questions. The NRA, I’m not sure if I should even mention the NRA here, but the NRA, one of their big focuses is on gun safety. Is there anything out from the NRA on dementia and guns or is this just-

Alex: Are they silent on this issue?

Eric: Is this not their lane?

Emmy: So far there has not been anything specific from them. They have, in general, the safety things. The NRA is still the biggest, what do you call it? Distributor or firearm safety courses. I’ve taken their course, and it covers all the basics of handling and safe storage. Importantly, these central tenants of unauthorized people should not have access to your firearms. It does talk about certain … People at certain times shouldn’t have access or shouldn’t be able to use them.

It doesn’t talk specifically about dementia. I mean, there are people in the firearms community, layers, who work with things like gun trust to help give your guns to the next generation. I think it’s out there. We’ve had a lot of interests form the firearm community that we work with here. We’re gonna actually start maybe developing some brochures and things to actually distribute through ranges about how to think about loved ones and warning signs to look out for.

Eric: Didn’t you also talk about, what was it, a firearms directive? Actually putting into writing what you do with your firearms as your dementia progresses.

Emmy: Yes. That was an idea that … I would love to know if anyone uses it. Any listeners, please use it and then let us know what you think. There’s a similar thing for driving. To me, it’s a conversation starter. It’s not legally binding, but would it help to get families thinking about it? Early stages of dementia or cognitive impairment. Or just pick an age. “Hey dad, when the time comes, who do you want to have your guns?” To start thinking about it. Or if you became impaired, who would you trust to tell you about that? Maybe it’s a friend. You know, it’s one way potentially to start the conversation. I’d love to know if it works.

Alex: Right. Or if you became impaired, who should have your guns in that case to hold them for you?

Emmy: Yeah. I wanna give a shout out to Alzheimer’s San Diego, which is a local organization. They’re doing some really cool work partnering with The Big Range out there, both providing dementia information to the Range, but they’ve also had now some firearm training for their employees who do a lot of Alzheimer’s related work to help them basically be able to have better conversations with families about this.

Eric: The thing I love just listening to you, you’re really not taking a stance that … I’m gonna go back to the quote. You’re not a self important anti-gun doctor. You’re not anti-gun. You actually wanna work with the gun community. You’re actually involved in it. It sounds like you’re taking safety courses. You’re well versed in this. It’s about relationships and partnerships.

Emmy: I mean that’s my take. I’m open about this. I’m not a gun owner myself and I probably won’t be, just because of my lifestyle and I don’t really feel like I need one. But I really feel like, especially as healthcare providers, we need to meet our patients where they’re at, and this is a … I mean, it’s a cultural factor in this U.S. that … It’s in the U.S. that it’s not … There are a lot of ways to help people be safe. One of them is to not have any firearms at all in the home, but there are other options too. How do we help people make patient centered decisions to promote health and safety. To me, that’s what this should be about.

Alex: That’s terrific. I wanted to also just make sure that we’ve covered enough about your interactions with the gun shop owners as well. It sounds like they’re thirsty for this, they recognize this as an issue. Have they sold guns to people and wondered, “Should I be doing this? I’m worried about this person. How do I screen them for dementia? Is that my role?”

Emmy: Yeah, all good points. I think for listeners who are wondering, people who work at gun shops absolutely have the right to refuse a sale for any reason, really. There’s been a lot of work over the past decade in the suicide realm of partnering between public health professionals and suicide prevention, and recognizing warning signs for that, and educating gun owners through gun shops. Including now a national program from the Firearm Trade Association, and the National Suicide Prevention Group. I really hope that the dementia thing can be the next piece of that. How do we get information out to family members, to ranges, to help people proactively make these decisions?

Eric: Now, what do you say to the person who says, “This is just a ruse. The first step in people trying to enact gun control.” You pick a problem that just, I see this in the comments, that we don’t even know if it’s a problem. It sounds like you think it’s a problem. But it’s really a ruse for a larger gun control, government taking away my rights.

Emmy: Yeah. I hear it a lot, so I’m sort of used to it. I think I would say … I’m not trying to claim this is as big an issue as some other … When you look at the firearm injury pie, this is a very small segment, but for families dealing with this, it’s a big deal. I would argue that makes it important. You know, I guess I just try to keep repeating the same things over and over again.

Well first of all, I hope we could all agree that someone with significant dementia, shouldn’t have access to lethal things. I mean, I hope that even that safe gun owners would agree with that too. Responsible gun owners would say, “Of course you need to be responsible.” I think it’s incumbent upon us doing this work to keep reiterating that it’s not about confiscation. There are probably gonna be people who all will not believe that, but it takes time to build up trust and relationships. We’ll just keep at it.

Alex: That’s great. Anything else you wanna talk about Emmy?

Emmy: No. I just reiterate, if listeners have thoughts, experiences, etc., data, please get in touch, because it’s a growing area and we’d love to know what’s going on.

Alex: There’s a lot of work to be done in this area.

Eric: It sounds like from a practical standpoint, as far as the key take home I’m gonna remember from this is, as a practicing clinician, when we’re making a diagnosis of dementia, at the very least we should be asking about guns and gun safety, and gun storage. Maybe also thinking about, does a firearm directive. Starting to think about, what would you do as your dementia progresses, and involving caregivers and family members, seems like a good start. Is that right?

Emmy: I think so. Again, remembering, put it in context of other safety issues. It’s like, “Hey, we’re gonna talk about the home and driving, and all these things.” One point I did make that is very important, there are no state or federal laws right now that prohibit healthcare providers from talking about firearms with patients. People sometimes think that there are. No. It’s okay, you can do this. It’s legal.

Eric: That whole Florida fiasco.

Emmy: Forget it.

Eric: Forget it.

Eric: Alex is looking confusing. In Florida, what happened in Florida? I guess a lot of things happen in Florida.

Emmy: Yeah, so in Florida there was a law that said physicians couldn’t talk about firearm safety, although there actually were specific clauses of when someone was at eminent risk of self-harm. It went to the courts, it eventually was struck down. Was not in effect. There’s no other current state law, no federal laws. It’s okay. Go stay in your lane, but remember it’s not about politics, this is about, how do we help people. Right? You guys in geriatrics and palliative care, you’re the masters of patient centered care. Embrace it.

Alex: That’s right. That’s great. That’s terrific. Thank you so much Emmy, this was awesome.

Eric: Yeah. How about we end with a little bit more of that Johnny Cash song.

Alex: Want more Johnny Cash? [Singing]

Eric: That was a perfect Johnny Cash right there.

Alex: That was fun.

Emmy: It’s good. But he does take him to town and then he dies. He should have left them at home.

Alex: Yeah, right, in the end of the song he takes them to town. Yeah.

Emmy: He takes them to town and then he dies. He would have had a lovely time in town.

Alex: If he’d listened to his family.

Eric: Oh, if he’d only listened to the family.

Emmy: He can still own them, just don’t take them to town.

Eric: Well, to all of our GeriPal listener family, thank you for joining us this week. We look forward to our next podcast next week. Emmy, thank you for this wonderful discussion. Again, to all our listeners, if you’re listening to us on iTunes or some other app, please take a second to rate us so we can share the wealth. Goodbye everybody.

Alex: Bye. Thanks Emmy.

Emmy: Bye.