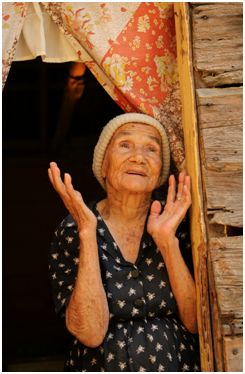

There is a lot of focus on what elders with dementia can’t do. But what about more discussion of what they can do? When you see a patient with dementia, how do you help family members maintain meaningful interactions with their loved ones? I am sad to admit that I don’t do this nearly as well as I should. After all, this is not the type of thing we are taught in our training.

The most recent posting from the wonderful New Old Age Blog in the New York Times, from guest blogger Dr. Cynthia Green, has some useful, practical advice. As she states, “the trick it do find activities that are engaging, yet doable.” The general gist is to find activities and hobbies that the person has enjoyed most of their lives and make modifications so they can still do parts of them. For example, perhaps Grandma loved to cook. Maybe she can’t cook a meal anymore, but mashing the potatoes, icing the cake, or using the cookie cutter may be very meaningful to her and give you something you can do together.

One of the best parts of this posting are the wonderful comments from family members. There is a treasure trove of useful tips and suggestions about what has worked in different situations. Several family members noted that when they stopped mourning what their loved ones could no longer do, and instead learned to find joy in activities they could do together, their stress decreased and they found new meaning in their relationships. I wonder if I would do more good for my patients by just referring them to these snippets of advice than by writing another donepazil or memantine prescription.

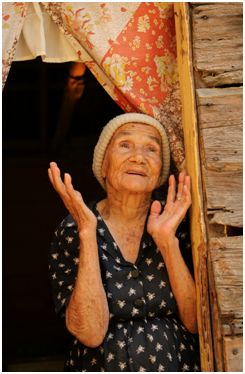

The post is making me think about a number of issues in terms of the how we learn to care for patients with dementia, and the dominent research paradigms in the field. We are rather dominated by a model in which the focus is on reversing and/or preventing declines in cognitive function. The problem is that current options, when directed towards that goal, are quite poor. Would management of dementia be improved if the “cure” paradigm were replaced with a quality of life paradigm?

And why is there such limited research into practical approaches such as these towards improving quality of life and well being in persons with dementia? Why don’t we ever see any research examing this type of issue in medically oriented Geriatrics and Gerontology journals?

This is exactly the kind of area where a Geriatrics and Palliative Care collaboration could improve how we care for patients with dementia. We need a model that more explicitely recognizes dementia as not curable and minimally preventable–something that will be true for at least the intermediate future. At the same time, our model needs to be emphatic that incurable does not mean hopeless, or that there is nothing we can do. The research and clinical model needs a much more explicit focus on quality of life. Geriatricians need Palliative Care clinicians and researchers to partner with us in this endeavor. This is a great model for why Palliative Care needs to be about much more than the last 6 months of life.