In 1968 a committee at Harvard Medical School met to lay down the groundwork for a new definition of death, one that was no longer confined to the irreversible cessation of cardiopulmonary function but a new concept based on neurological criteria. Over the next 50 years, the debate over the concept of brain death has never really gone away. Rather cases like Jahi McMath have raised issues of the legitimacy of the neurologic criteria.

On today’s podcast, we talk with one of the leading international thought leaders on Brain Death, Dr. Robert Truog. Robert is the Glessner Lee Professor of Medical Ethics, Anaesthesiology & Pediatrics and Director of the Center for Bioethics at Harvard Medical School. He has also authored multiple articles on this topic including the Hastings Center Brain Death at Fifty: Exploring Consensus, Controversy, and Contexts and these from JAMA:

- The 50-Year Legacy of the Harvard Report on Brain Death

- Understanding Brain Death

- Brain Death—Moving Beyond Consistency in the Diagnostic Criteria

In addition to talking about how Robert got interested in the topic of brain death, we discuss the history of the concept of brain death, how we diagnose it and the variability we see around this, the recent JAMA publication from the World Brain Death Project, why brain death is not biologic death (and what is it then) and what the future is for the concept of brain death.

Eric: Welcome to the GeriPal podcast. This is Eric Widera.

Alex: This is Alex Smith.

Eric: And Alex, who do we have with us today?

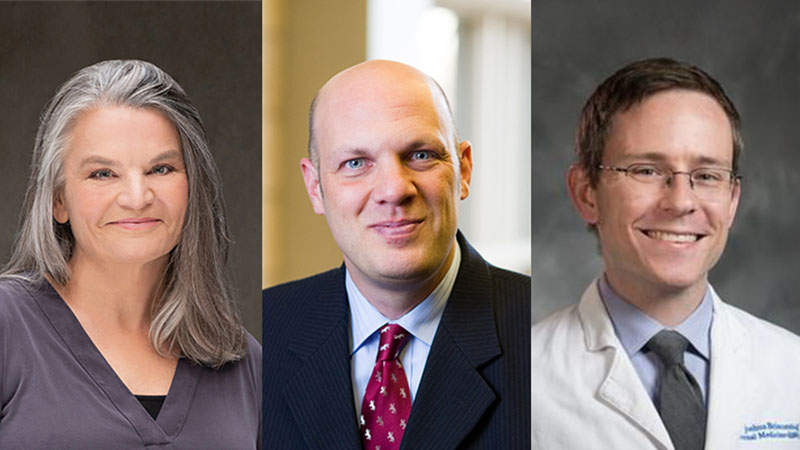

Alex: Today we are honored to be joined by Bob Truog, who is the Francis Gleeson Lead Endowed Professor of Legal Medicine and the Director of the Center for Bioethics at Harvard Medical School. I believe, that he is the first pediatrician we have had on the Geriatrics and Palliative Care podcast. Welcome to the podcast, Bob.

Bob: Happy to be here. Looking forward to it, yes. I’m not surprised I’m the first pediatrician you’ve had.

Alex: And we are also delighted to welcome a guest host, Liz Zhang who is Assistant Professor of Hospital Medicine at UCSF, as MV PhD very, interested in ethical issues. Welcome to the GeriPal podcast Liz.

Liz: Thank you. Great to be here.

Eric: No, we are not switching to a pediatric palliative care podcast, we’re going to stay as GeriPal and today we’re going to be talking about brain death. We’re going to be referring to Bob’s recent multiple editorials on this subject in GAMA, which we’ll have links to on the GeriPal podcast show notes, but before we get into that subject we always start off with a song request. Bob, do you have a song request for us?

Bob: Yes, well I thought given the subject that the Grateful Dead should definitely be the band, A Touch of Gray actually has some nice lyrics in it that refer to our desire to survive. So I thought that might be the best accompaniment here.

Eric: Are you a dead head?

Bob: You know, yes. I guess I would have to say that.

Alex: First concert I ever went to, Grateful Dead and I was in eighth grade. I think this may have been their first song they performed. That was in Ann Arbor, wonderful.

Bob: I first saw them as a student at UCLA in Poly Pavilion, which was our big arena. That was one of my memories of freshman of college.

Eric: I have only heard the Grateful Dead once and it was actually not the Grateful Dead, it was Phil Lesh at Terrapin Crossing in Marin singing children’s songs. So, I can’t really speak of the Grateful Dead.

Alex: They live, well the remaining members live where we live now. So, there’s another connection. Okay here we go. (singing)

Bob: Well done. Well done. Thank you.

Eric: Alex, you really went up on the production quality here.

Alex: Maybe I went a little crazy there. It’s a lot of fun. Thank you for that song selection.

Eric: Alex has all his play toys going on in that song, right now.

Alex: I do. I do.

Eric: Bob, first very much appreciate having you on this podcast. So, we’re going to be talking about the subject of brain death, which is an issue both in geriatrics and palliative care. For anyone taking the palliative care boards coming up in about a month, incredibly important topic for the boards too. You’ve got to know a little bit about this. Bob, how did you get interested in this as a topic? Because you’ve been focused on this for a while.

Bob: A lot of people say I’ve been obsessed with this for 30 years, yeah. I actually remember distinctly, I was at Denver Children’s Hospital in the Intensive Care Unit and we had a morning lecture and the speaker that morning was teaching us about brain death and he taught it just like any other medical diagnosis. You do these things, you test these certain things and then you make this diagnosis if the person is dead. Here’s the criteria for ARDS. Here’s the criteria for acute renal failure. You memorize it and that’s it.

Bob: I can remember going home that evening and thinking, “Now, wait a minute.” Why is it so clear that this means that a person is dead? They don’t look dead. It’s just stayed in the back of my mind and I would ask you as physicians, most of us are taught brain death that way. That, here’s this test and then the person is dead. It really was a number of years later before I started to think more deeply about it and started to ask questions as to why.

Eric: It’s really fascinating. I feel like in medical school and in residency training, at least in internal medicine, we don’t spend a lot of time on the topic of death or determining death. The very little time, even from a medical standpoint talking about cardiopulmonary death and how to think about that, or even death certificates. So anything that happens after somebody dies, we don’t spend a lot of time on. Can you describe how did this even come up, what’s the history of brain death? Where did this come from?

Bob: If you go back to the years following World War II where advances were made in how to keep people alive with a mechanical ventilator, there were people who were noticing that there were patients who absolutely would have died from a devastating brain injury, except they get put on a ventilator and they end up living for a long period of time. The first article about this comes from French physicians and they refer to this state as coma depasse or beyond coma. There’s a beginning of a discussion about whether, even though they’re being kept alive on the ventilator, should we consider them to be alive since the brain injury is so devastating? That was how it started.

Eric: And around that time, so currently the way we were diagnosing death is by irreversible cessation of cardiopulmonary function?

Bob: Right. That was the standard up until that point. Where it really all came to a head was in December 1967. So, Christian Bernard performs the first heart transplant in Cape Town. He comes out to do the press interview after the operation and one of the journalists says, “Was the donor dead before you took out the heart? Or did you kill the donor when you took out the heart?” Christian Bernard was not prepared for this question. I guess his brother, who was much more articulate than he was, managed to fumble his way through it. But, Henry Beecher who was an anesthesiologist at Massachusets General hospital recognized that this was a huge career opportunity. That if we’re going to advance the field of organ transplantation, it’s got to be the case that these patients are considered to be dead before we take out their vital organs, because nobody wants to think that we’re killing them in order to get their organs.

Bob: So he went to the Dean of the Medical School and he forms this committee at Harvard, the ad hoc committee and they were the ones who took that idea of come depasse and actually propose that maybe there should be a new way of thinking about death.

Eric: And then, moving forward to now. So GAMA just published this really wonderful, and we’ll have links to it on the GeriPal website, World Brain Death Project summary of the termination of brain death and death by neurological criteria, which has probably the most amount of supplemental content I’ve ever seen before. Seventeen different supplementals, which are all incredibly fascinating to read. Why this now? Why try to have this consensus statement and recommendations about what brain death and death by neurological criteria? Did we resolve it 30 years ago?

Bob: Hardly. Well, I say hardly. I think, you mentioned it people are going to be taking their boards. I would say don’t listen to what I’m saying in terms of taking your boards, because my views about this are not the mainstream views. But, I hope to convince you that they are reasonable. The main focus of that project was to address a big problem, which is that the actual criteria for making the diagnosis are highly variable around the world, but even within our own country. Different hospitals have different guidelines. So, the main point of that was to come to consistency about what the tests are.

Bob: The point I tried to make in the editorial was that you can have perfect consistency about how you make a diagnosis, but if you don’t know what it is you’re trying to diagnose, it’s potentially meaningless. There has to be some underlying state that is your gold standard, and then it makes sense to say “Okay, now what are the tests we need in order to make sure that we are actually diagnosing this gold standard.” The problem is, that there’s been great controversy about what the gold standard for brain death is.

Eric: Now is it that you’re advocating that, am I getting this right? It’s irreversible apneic unconsciousness? Is that the gold standard? Is that what we’re trying to achieve here?

Bob: Well, that’s what I argue.

Eric: Why is that?

Bob: Let me go back and just say a little bit about the history of this because the big question is, is brain death just a different way of diagnosing traditional death? Or is it a new way of understanding what it mean to be dead? Going back to Henry Beecher in 1968, it was pretty clear that he thought this was a new understanding of what it means to be dead. That even though biological life continues, he believed that this is somebody who is never going to wake up and if you’re never going to wake up then the meaning of being alive is gone. We can consider you to be, dare I say, as good as dead. Even though biological life is continuing.

Bob: Now, 1968 we have the first paper from the Harvard Committee that talks about brain death, but then there’s a bit of chaos because through the 1970s, some states had brain death in their laws, some didn’t. So, in 1981 I believe, they decided we can’t go on like this. So they made a standard understanding of brain death. This was called the President’s Commission at the time. What they said, was that nope, there’s only one type of death. It’s biological death. Just like cardiopulmonary arrest. The reason that brain death is biological death is because when the brain dies, the body needs the brain in order to maintain integrated functioning. When the brain dies, the body literally disintegrates, falls apart just like it does after cardiac arrest. That was the beginning of the controversy. Is brain death the same as biological death or is it a new understanding of death?

Liz: And you speak of this in your editorial, but I think there have been some really interesting high profile cases over the last several years, Jahi McMath, somebody in California who was declared brain dead, but continued to grow and even have a menstrual period and you also speak in your article of somebody who made it through pregnancy, somebody who lived several years. Other people who have lived several years. How has that affected this controversy? Were those cases the impetus for you to think about other ways of conceptualizing this?

Bob: Yeah. We’ve known for a long time that if you do continue, I’ll say life support, on a patient after the diagnosis of brain death, that they can live for a long period of time. Allen Shuman is the neurologist who is really carefully documented a number of these cases, but they were pretty much invisible because as you know in your practice, once you diagnose somebody as brain dead one of two things happens. Either they become an organ donor, or we fill out the death certificate and we take them off the ventilator. So that once that diagnosis is made, biological death almost invariably follows within a matter of hours to a couple of days.

Bob: So, it was not widely recognized that if you didn’t stop that ventilator that patient might actually go on and live for a long time. This was where the world of social media really changed the ball game, because we had Jahi McMath, a young woman how has a post operative hemorrhage from tonsillar surgery basically at Oakland Children’s hospital and her family is black and I think they were not treated well. They got angry.

Bob: So instead of the normal process, which is the doctor’s come in and say, “We’re very sad to report, but your daughter is brain dead. Now we need to talk about organ donation or turning off the ventilator.” They got a lawyer and they got legal injunctions. There was no doubt that she meet the criteria for brain death, but long story short, New Jersey has a religious exemption for brain death and their lawyer found a hospital in New Jersey that was willing to accept her and so he was transferred from San Francisco to New Jersey, and not surprisingly, but people hadn’t really known about this before, she went on to live for almost five more years until she succumbed to liver failure.

Bob: Most of that time was not in an Intensive Care Unit. Almost all that time she was in an apartment with her mother. She had some occasional hospitalizations, but for the most part, lived like many other people with severe brain injury live, on a ventilator. She continued to grow, as you mentioned, she went through puberty. So very much looked like an otherwise living person, just with a severe devastating brain injury.

Eric: That’s fascinating, I think one of the challenges to is even how we describe it. Because I think technically she was dead in California, death certificate was filled out, but alive in New Jersey and it’s even weird to say, “Four years later she died”, when from a California standpoint she was dead, but a New Jersey standpoint she was alive.

Bob: Yeah, very confusing.

Eric: State lines are amazing how they do that.

Bob: Yes. But you know, that’s the point. If brain death were the same thing as biological death, we wouldn’t be having this conversation. Biological death does not respect state lines. If you had a cardiac arrest and you die, it doesn’t matter what state you’re in.

Eric: Isn’t it fascinating though what we… I think part of the challenge that we have is in order to define death, it’s the lack of life and in order to define life it’s not being dead. How do we actually, and I think this is the struggle right. At what point is somebody biologically dead as well? Is it because their heart and lungs stop beating? More than that, because we can restart it. Is it the irreversibility of it, what do we define as irreversible? Henrietta Lacks, her cells are still living. Is a part of her still alive? It’s hard.

Bob: Well, it is and it isn’t. Let me say why I think it’s not that hard. Is that we have a very intuitive understanding of death. If we were to walk outside right now, you’d be able to point out that tree is dead. Here is an insect on the ground, that’s dead. We know when our pets die. I think that there is a rather uniform understanding of biological death that’s true across the entire biological spectrum. It’s where an organism is able to oppose the entropic forces that are causing disorder using ATP and other energy consuming things in order to maintain homeostasis. As long as that balance, that homeostatic balance is there, we would say an organism is alive. We can talk about an amoeba, a tree, a dog, a person. When that homeostasis is gone, that’s when death occurs.

Bob: I think from a biological perspective it’s actually not that complicated. But when we say that we’re going to consider you to be the same as dead, for a human being when we know you’re never going to wake up or never breath again, that’s really a value choice that we’ve made. That’s not a biological fact. We’ve made a value choice that is a life that we are not going to consider anymore to be alive.

Liz: I think what’s really interesting about this is that this really didn’t become a controversy until we developed the technology, the ICU technology to create mechanical ventilation, dialysis, that sort of thing that keeps you alive. I think what’s so interesting is that I feel like the ethics of end of life technologies hasn’t really caught up with our technology development. I think that’s just really interesting because whenever we have these new technologies it changes the way we think about death. It changes the way we make decisions around it, and just talking a little bit about my area of research, it also changes the aggressiveness of care that we have at the end and the inability to think about palliative care and so, I just think that’s really interesting.

Bob: I think one of the big controversies in end of life care, whether it’s pediatric or adult is, when can we say that treatment is futile? I’ve not been a big fan of the concept of futility in my life, but there are times and certainly in my world of doing intensive care medicine, there are times where I really believe the continued treatment is absolutely not going to work and a number of hospitals do have futility policies that allow the clinicians to act on that. Usually with an ethics consult, and can go ahead and withdraw the ventilator without the permission of the family. Some places use these policies pretty routinely, they’re not that popular in pediatrics, but I don’t know what your experience with them has been.

Bob: My point is that I think that brain death is somewhat similar to that. When you reach a point that person is never going to wake up again, never going to breathe again, I think it does make sense to say that further treatment would be futile and treatment should be stopped. It’s just that the reason for doing it isn’t because they’re already dead, because they’re not. The reason for doing it is because further treatment is not of value, is not beneficial.

Alex: So you argue that we should go back to what Beecher proposed, which is that there’s a separate conception of brain death that is distinct from biological death and that people would have the ability to op out of this as they have in New Jersey, which hasn’t resulted in major challenges. Is that a fair summary of your argument?

Bob: Yes it is. I’m not saying we should go back to what Beecher did. I think Beecher was simply right about what brain death is. It’s a value judgment about when we can consider a person to be dead. This is a more complicated thing. I don’t necessarily think that every patient should then have the option of opting out. For the reason that I just said. I don’t think that it makes sense for us to keep brain dead patients in Intensive Care Units. I think it’s non-beneficial treatment. Whether we say it’s now a new definition of death, or whether we say that the treatment is futile and we’re going to stop it regardless is kind of the same thing.

Bob: So, what they’ve done in Great Britain is, they’ve basically said if you’re never going to wake up and you’re never going to breathe again, we are making a values based judgment that you are dead. By law, we are going to treat you as if you are dead. I don’t think there’s anything wrong with that. I think it’s just important to recognize that it’s not a biological fact it’s really a value judgment that they’re making.

Liz: I think that what’s so fascinating about all of this is that it’s not just a medical thing. It’s not just a biological decision, but there is metaphysics. There is morals. There is religion and culture. I was wondering if you could speak a little bit about how those factors come in to play in consideration of this particular argument that you’re making and in general around issues of brain death.

Bob: Yeah. I think there’s been a lot said that brain death is accepted worldwide. I think that is a big over statement. So, in the west if I may, the western view is that we are our brains. So, if you look in North America, western Europe, brain death is widely accepted. If your brain is gone, you might as well be dead. That view isn’t as predominant in eastern cultures, tend to have a more holistic view about what it is to be alive.

Bob: For example, in Japan, there’s been a great deal of controversy about acceptance of brain death. I think one of the reasons that brain death has made in roads in eastern societies is because if you want to play a part in the world of transplantation then you need to have a way of procuring organs. Unless you’re going to say “It’s now okay to kill people to get their organs”, you’re going to have to buy into this notion of brain death. Because it’s the only way that you can really procure those organs and be able to tell ourselves plausibly that we did not kill the patient in doing so, they were already dead before we started.

Bob: So in Japan and China and really any advanced nation, organ transplantation saves lives. I’m a huge supporter of organ donation, organ transplantation. But if you want to have that in your society, you have to also buy into the notion of brain death.

Eric: And the GAMA consensus statement, at the very end there’s an advocacy piece that sounds like they also recommend that all countries recognize brain death and death by neurological criteria as legal death. How do you feel about that recommendation?

Bob: I think, first of all, did they actually say legal death? Is that the wording that’s used there?

Eric: That is the recommendation number one under BD/DNC and loss. Brain death and death neurological criteria is recommended that all countries recognize it as a legal death.

Bob: I’m quite supportive of that actually. To say its legal death is I think accurate. It is a legal distinction that you are as good as dead and we’re going to consider you to be legally dead. What I like about that, is that it implicitly recognizes that these patients are not necessarily biologically dead and that if support were continued, they might live for some long period of time. I think that societies basically can choose that. What I really like about what the UK did is that they were just so explicit about it. They just said, “This is not biological death. We know it’s not, but in our society, it’s legal death.” That then becomes the foundation for the ethical practice of procuring organs for transplant from these patients.

Alex: I wat to take a brief moment to lighten the mood for a moment and talk about movie tie ins. I was surfing YouTube earlier and you have this magnificent story that you told McLean Center when you were a guest about what happened in the Wizard of Oz. I wonder if you could tell that at the beginning of the Wizard of Oz, I wonder if you could tell that story.

Bob: Gosh, I wish you’d give me a little prep so I could have gone back and looked at it, but you can remember that the house falls on the, was it the wicked witch of the west, right? The munchkins come out and they don’t know, is she really dead or not? So they call the coroner and he says something like, “She’s not only merely dead, she’s really most sincerely dead.” And I think it makes the point actually, coroners are often not physicians, but it’s where a person of authority, we need a person of authority to come out and say, “Yes, this is really death.” Or it’s really legal death at least, and that’s the role that the coroner played in the Wizard of Oz.

Alex: It gets to this issue of why is this so important? Why is this moment of transition to death, some sort of death so important to us and it also gets at my question to you Bob. I remember you advocated for this proposal, this idea when we met several years ago, why isn’t it policy? Why isn’t it law in the United States? What are the forces, the countervailing forces behind this move?

Bob: Well, I can only speculate but we are very polarized society right now. I think there’s a fear that to openly acknowledge that brain death is not biological death it becomes a crack in the door for some version of a pro life argument that if it’s not biological death, they’re not really dead and if you take out their organs, you’re killing them.

Bob: I think that people have a great deal of fear about that. That being said, we do know that New Jersey has basically allowed people to opt out of brain death for over 25 years. We haven’t seen any sort of a movement like that in New Jersey. Of course New Jersey is New Jersey and how would it play in other states, I don’t know. But this is where I think I really have concerns about obfuscating the facts in order to promote good policy. I agree. I want to see people feel confident in the organ transplantation system. I want them to know that we’re not going to kill people for their organs. At the same time, I think we want to be honest about what brain death means. I think to say that, oh when you’re brain dead, you’re biologically dead, is simply not true. So, where do you find that balance between promoting good public policy and telling the truth?

Liz: This is a very complicated topic for people who are experts like you I the area, but also for doctors and then for the general public. I’m just curious, how do we even garner that understanding of what the public opinion is, be that of clinicians or of the general public. How do you get a sense of even what people want or prefer?

Bob: There’s been some good sociological research done on this. Michael Near Collins is a sociologist who’s done a lot of it and just to really summarize his work in just a sentence, it turns out that for about 70% of people, if you present the with a patient who is on a ventilator, never going to wake up, never going to breathe on their own, is it okay to donate their organs? Is it okay for the doctors to remove the organs? Would you allow your organs to be removed if you were like that? About 70% of people say yes, and it has nothing to do with whether the patient is dead. For about 30%, it matters a lot as to whether the patient is already dead. So, what do you do with that information? I think if 30% of our population were really upset about what I would say is the fact of what brain death means, I can understand why people are concerned about speaking the truth.

Eric: Can we go to the target. When we’re saying brain death, what are we actually saying?

Bob: Yeah, thanks for the question. Because I do think it’s actually very clear and I think there’s advantages to recognizing what it is. It is a state of irreversible apneic unconsciousness.

Eric: And can we just describe why all three of those are important? I get the irreversibility. So making sure that there’s not something that could be fixed, some reason like they’re really hypothermic. There’s a diagnosis that’s consistent with it. That’s what we’re looking for.

Bob: That’s right. And irreversibility is always a tenuous claim because as soon as you have one case that isn’t irreversible then you’ve blown the whole thing out of the water. So, we make assumptions about irreversibility and I’m comfortable with it. I think that the injury that these patients have is very severe and some concerns have been raised. Neurologist Allen Shuman really believes that Jahi McMath had recovered to a minimally conscious state at one point. He may be right, I don’t know. He’s pretty convinced he was right about that and that would disprove the irreversibility hypothesis and the way we diagnose brain death.

Bob: Unconsciousness, I think it’s interesting. We don’t do very sophisticated testing for the lack of consciousness. Mostly the part of the brain death exam is nothing more sophisticated than pressing on the sternum or pressing on the nail bed and seeing if the patient responds. We know that behavioral testing for unconsciousness is very unreliable. Patients who have been diagnosed as being in a permanent vegetative state for example, purely on a basis of the behavioral exam, we now know that those diagnoses can be wrong about 40% of the time and if you actually put those patients in FMRI machines, a significant number of them will show signs of consciousness even though they can’t demonstrate it behaviorally at all.

Bob: So, I think there’s room to bolster the claim that patients who meet brain death criteria are absolutely irreversibly unconscious. The part about apnea, you could say “Well, why does it matter if you breathe or not?”

Eric: That was my question. Why is apnea?

Bob: Well, patients who are in a PVS, very often we consider them to be irreversibly unconscious, but breathing and the notion that somebody who is breathing is actually dead, I think just runs counter to very deep psychological intuitions that we have that probably go back thousands of years in our thinking. So, I think that’s more of just almost a social thing. You can’t be breathing and be dead. So I think that’s where the apnea requirement comes into play.

Alex: I think of early medieval definitions of death, hold a mirror up to the face and see if it fogs. I think also of the caskets, the head of the pull mechanism so you can trigger a flag so that somebody above knows that they’re not dead. They’re alive. I also think I want to interject another movie reference, because this is fun and there are so many good movie references. Princess Bride. He’s not dead, he’s mostly dead. There’s a big difference between dead and mostly dead.

Bob: Famous quote, yes.

Alex: I did have a question, which I’ve forgotten with the Princess Bride, but Liz looks like you’ve got one.

Liz: I was just going to say that again, with mechanical ventilation though that’s made it much more difficult for us to have that very inherent gut notion that this person is dead. I remember situations in residency for example, where there was actually a lot of challenge in determining whether or not they were actually apneic because there was all the mechanical ventilation, all the other technologies complicating it.

Bob: Yeah, and even our intuition that if you’re breathing you’re alive and if you’re not breathing, maybe you’re dead. Look at the famous example of Christopher Reeves, Superman, with his cervical quadriplegia, he couldn’t breathe. Just like a brain dead patient can’t breathe and yet, no one would doubt that he was alive, right? So the correlations between breathing and being alive or being dead are imperfect at best. But nevertheless I think that has been one of the hallmarks of the diagnosis of brain death that I think would be very difficult to get rid of.

Eric: Can I ask another hallmark that we often see, brainstem reflexes how does that fit in? Why are they so important?

Bob: Great question. I think there’s a good answer for it. If you’ve been at the bedside when we do the neurological exam, we do these brainstem reflex testing very carefully. We get, for example, for the pupillary reflex, we have these devices now that can detect microscopic constriction of the pupils. So we’re very meticulous about that and yet, you might ask, why are we doing that? People can live just fine if their pupils don’t constrict. You don’t need those brainstem reflexes in order to do activities of daily living.

Bob: The reason that we do that is because there’s a structure in the brainstem called the reticular activating system, which is responsible for wakefulness. For example, for patients in a PVS, it is still active and that’s why they have sleep-wake cycles. We can’t actually test that. There’s no way of testing that, but the RAS is surrounded by these brain stem nuclei. So by testing for those brain stem reflexes and knowing that they are gone, we infer therefore that the RAS is also non-functional. If the RAS is non-functional then by definition the patient cannot be conscious.

Bob: So it’s a supplementary way in addition to pressing on the sternum, pressing on the nail beds, it is a supplementary way of knowing that this patient really is unconscious.

Alex: I’ve got a couple more questions. First one, what would we call this term that is distinguished from biological death? Would we call it brain death and call it separate? Would we call it irreversible apneic state? And would that provide comfort to families who want 30% of individuals who are uncomfortable removing life sustaining treatment from a person who is in such a state without knowing that they are dead.

Bob: I think the most accurate way to put it is that when we do the testing, we determine to a high degree of probability that this person is in a state of irreversible apneic unconsciousness and that in our country, we have a law which says that if you are in this state you are legally dead. I think that’s the most accurate way of putting it. When I make the diagnosis of brain death, I work in Pediatric Intensive Care, I do say, this is what I tell parents. That their child is never going to wake up again. They’re never going to breathe again. And in Massachusets under the law, their child is legally dead.

Alex: Mm-hmm (affirmative). It does get to that point, dead. They are legally dead. This raises another key question, which is state wide variation. My question is, looking at the United States at this time, what proportion of states or are there just a few that currently recognize irreversible apneic unconsciousness as legally dead and is that distinct from this conception that brain death must lead, in other words which states are already on board with this proposal? You mentioned earlier that there should, in the future be some federal policy. Do we need to drive towards state wide change first or should this be a top down approach from the federal government?

Bob: Well, first of all, all 50 states recognize irreversible apneic unconsciousness as legal death. All 50 states. The only difference is the degree to which they allow families to disagree that that is really death. So, New Jersey is the only one that has a true religious exemption. New York, I believe California has softer language that you should provide accommodation for religious beliefs, which usually means just delaying the diagnosis a little bit longer. New Jersey is really the only one that allows you to opt out.

Alex: So are we there or what are these legal challenges about then?

Bob: So the legal challenges are two fold. One is, if it’s not really biological death, is the law legitimate? So that’s one. The other that we haven’t really talked about is that, the actual law on brain death in the United States requires, “the complete absence of all functions of the entire brain including the brain stem”. That’s the law. If you look at the testing that we do for brain death, it only tests certain functions, and in particular we now know that there are patients who do retain hypothalamic functioning. Mainly things like temperature control and regulation of the vasopressin secretion. Which you could argue are pretty important brain functions. You need your brain to regulate your temperature and to regulate your fluid balance. They are not tested, they are not part of the brain death testing and yet, some patients do retain them.

Eric: Jahi McMath was one, right?

Bob: Jahi McMath was certainly one, right. So here’s the paradox, you can completely fulfill the American Academy of Neurology criteria for brain death and not fulfill the law, which requires the complete absence of all functions of the entire brain. I think that’s actually the biggest vulnerability that our law has right now. Increasingly we’re seeing a number of legal scholars recognize that this is a big vulnerability. The tests that we use don’t actually meet the requirements of the law. So, we are going to have to go back and revisit the law in some way and fix that inconsistency.

Eric: The good news is, we have a well functioning government that can easily tackle difficult issues like this.

Bob: Um, yes. But less cynically, the good news is actually that there’s an organization in Washington called The Uniform Commission or State Commission or something like this, that do develop these uniform state laws and my understanding is that they have agreed to reconsider our brain death law specifically to address these problems. So we’ll see how that goes.

Alex: It strikes me that there is generally, you asked before about this question 30% of people would be uncomfortable removing life sustaining treatment from persons unless they were declared dead in some way, I guess one of the key drivers as you mentioned, this goes back historically to 1967, is transplant.

Bob: Yes.

Eric: I suspect there’s broad agreement about the importance of transplant within the United States and around the world as you mentioned. My question is, of course we want to do transplant for really compelling reasons because we can save lives of people who would otherwise die. Is there also a financial reason? Are there financial, transplant is big money. Are there big money drivers towards changing that have a vested interest in changing this definition?

Bob: I’m actually a little less cynical than you are. I think that yes, of course transplant is big money, but transplant also saves a lot of lives. But here’s the question that occurs to me is that we are fairly well advanced at using crisper technology to edit pig genomes in order to overcome the immunological barriers to using, and infectious disease barriers, to using pig organs for transplantation. Let’s fast forward five to 10 years and let’s say that we can use pig organs and they’re the perfect size and they’re in virtually unlimited supply and now the ethics of using these organs is really not much different than the ethics of whether you eat bacon.

Bob: We suddenly no longer need organs from people. Will we even need a concept of brain death? I have this vision that you’ll get Harrison’s textbook of medicine in 20 years and you’ll go to the index and you won’t even find it. Because it was a social construction that for a particular historical time where we needed to get organs from people and when the need for that is gone, the need, I think, for the concept will be gone. Then we’ll be back to what we do every day, which is to talk with families about, what is the prognosis and does it make sense to continue with life support? For people that are never going to wake up again and those sorts of things. We’re going to say it was time to withdraw the ventilator, just like we do now. But we won’t need to have this social construct that we call brain death.

Eric: And there’ll probably be a greater proportion of people that are being kept alive in an irreversible unconscious apneic state.

Bob: Maybe so. Maybe a few more, but you know, my experience is that most families don’t want to keep their loved one alive in that state anymore than you or I probably would. There will be some. There will be the Jahi McMath’s, although even Jahi McMath’s mother said that if she had been treated differently she wouldn’t have insisted on continuing the ventilator. So, even there I’m not sure.

Eric: Communication.

Bob: Yes, exactly.

Eric: Really good communication, the importance of it. Well, Bob, I want to thank you for joining us for today’s podcast and taking the time. I thought this was absolutely fascinating. I learned a lot. We will have links to all your articles including, you mentioned a Hastings website.

Alex: Hasting Center report.

Eric: Yeah, Hasting Center report.

Bob: Yeah, if you Google Wiley, W-I-L-E-Y, which is the publisher and then brain death, Hastings Center report you’ll get the whole volume, it’s open access.

Eric: And we’ll have links to that too. So we’ll have links to all of this, but before we leave, Alex, do you want to give us a little bit more a little bit more dead head there?

Alex: A little more Touch of Gray? (singing)

Bob: I think you’re even better than the Grateful Dead. [laughter]

Eric: That’s a great song for this podcast. Also a great song for 2020. Bob a big thank you again or joining us.

Bob: Thanks for the opportunity, really appreciate it.

Eric: And Liz always great to have you on.

Liz: Thank you. It’s great to be here.

Eric: Big thank you to Archstone Foundation for your continued support for the GeriPal podcast and to all of our listeners, if you have a moment, please share this podcast with others on your favorite social media apps. Send out that tweet. Good night everybody.

Alex: Thanks folks.