I’m going to start this introduction the way Eric ended our podcast.

You are a GeriPal listener. Like us, you care deeply about our shared mission of improving care for older adults and people living with serious illness. This is hard, complex, and deeply important work we’re engaged in. Did you know that most GeriPal listeners have given us a five star rating and left a positive comment in the podcasting app of their choice? We will assume that you are doing the same right now if you haven’t done so already, though we suppose you are free to choose not to if you don’t believe in the mission of helping seriously ill older adults.

Ha! Gotcha.

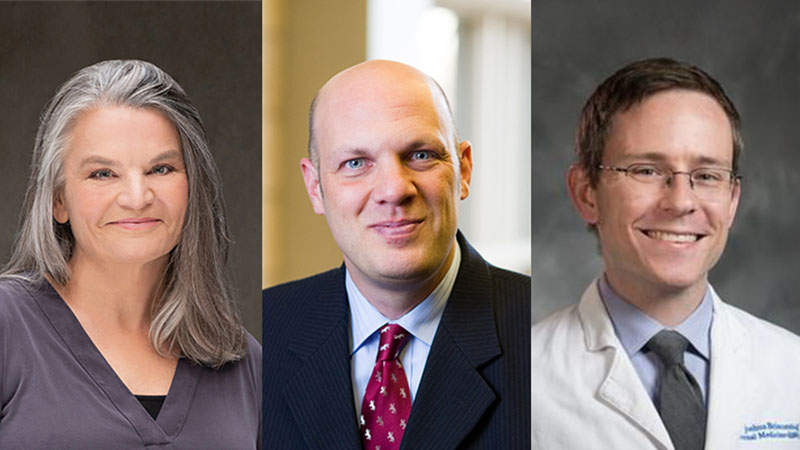

Today we talk with Jenny Blumenthal-Barby and Scott Halpern, two experts in the ethics and study of “nudging,” or using heuristics, biases, or cognitive shortcuts to nudge a person toward a particular decision, without removing choice. Jenny just published a terrific book on the topic, “Good Ethics and Bad Choices: The Relevance of Behavioral Economics for Medical Ethics.” Scott published several landmark studies including this study of changing the defaults on an advance directive (e.g. comfort focused care is checked by default) and a paper on how nudging can be used in code status conversations (e.g. “In this situation, there is a real risk that his heart may stop—that he may die—and because of how sick he is, we would not routinely do chest compressions to try to bring him back. Does that seem reasonable?”).

Examples of nudges are comparing to norms (most listeners have given us a 5 star rating), the messenger effect (I’m a believer in the GeriPal mission too, we’re on the same side), appealing to ego (you’re a good person because you believe in an important cause), and changing the defaults (you’re giving us a five star rating right now unless we hear otherwise).

We distinguish between nudges and coercion, mandates, and incentives. We talk about how clinicians are constantly, inescapably nudging patients. We arrive at the conclusion that, as nudging is inevitable, we need to be more thoughtful and deliberate in how we nudge.

Nudges are powerful. At best, nudges can be used to promote care that aligns with a patient’s goals, values, and preferences. At worst, nudges can be used to constrain autonomy, to promote “doctor knows best” paternalism, and to “strongarm” patients into care that doesn’t align with their deeply held wishes.

What will send your head spinning later are the thoughts we raise: what if nudging people against their preferences is for the common good? And also: what if the ease with which people are nudged suggests we don’t have deeply held preferences, goals and values? Hmmm….

Hey, have you completed your five star rating of GeriPal yet?

-@AlexSmithMD

Other citations:

Eric: Welcome to the GeriPal Podcast. This is Eric Widera.

Alex: This is Alex Smith.

Eric: And Alex, who do we have on, today?

Alex: We are delighted to welcome Jenny Blumenthal-Barby, who is Professor of Medical Ethics at the Baylor College of Medicine. Welcome to the GeriPal Podcast, Jenny.

Jenny: Thank you.

Alex: And we are delighted to welcome Scott Halpern, who’s Professor of Medicine Medical Ethics and Health Policy at the University of Pennsylvania. Welcome to the GeriPal Podcast, Scott.

Scott: Thanks, Eric and Alex.

Eric: Yeah, I think it’s interesting, Alex, you had a tough decision: Which of our guests would you introduce first? So many decisions we have to make on every single Podcast, every single day. How do you decide if it’s a good or bad choice?

Eric: So we’re going to be talking about decision-making, decisional architecture, nudges. I think a lot of this came out of… Jenny just published a great book called Good Ethics and Bad Choices: The Relevance of Behavioral Economics for Medical Ethics.

Eric: We’re going to be talking about that, some of the work that Scott has done too. But before we do, we always start off with a song choice. Who has a song request?

Scott: I’ve got one for you, Alex. What do you think about Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right by Bob Dylan?

Alex: All right. Well, this’ll be the third time. So, I’m going to do it on piano this time just to change it up. Why this song?

Scott: Well, the fact that others have requested it before speaks to what an amazing song it is.

Alex: There you go. Let’s see how many times we can nudge each other during this Podcast. [laughter]

Eric: That’s a cognitive bias, right? Isn’t that one of the-

Alex: I think that was norm or something like that.

Scott: This is what nudging is all about, right? We want people to think. But not too much, not twice.

Eric: I’m pretty sure how Alex asked the question about which song…he steers people to Bob Dylan. [laughter]

Alex: I don’t know. I’m worried now that by the end of this Podcast, Jenny and Scott will be the interviewers. They’re going to take over the GeriPal Podcast because they will have nudged us out of the way.

Eric: Yeah, exactly.

Scott: I just wanted to make the claim that rational people do not need to be nudged toward Bob Dylan. It just happens organically. [laughter]

Alex: Before we get too far into it. (Singing).

Scott: Outstanding.

Eric: Mixing it up with the piano. I like it, Alex.

Alex: Mixing it up a little.

Eric: Well, let’s dive into the topic. I’m hoping first, just to describe a little bit of one of these big terms mean, then I’d love to hear from both of you, how you got interested in in particular behavioral economics nudging, and choice architecture. Before we talk about how you got interested, what the heck are those things? What’s behavioral economics?

Jenny: I’m going to let Scott explain what behavioral economics is.

Scott: Oh, wow.

Eric: That was a little more than a nudge there. [laughter]

Scott: Yeah. That was a show off, Jenny. [laughter]

Jenny: A transparent nudge.

Eric: Yeah. Aren’t you supposed to appeal to his ego? Isn’t that one of the-

Jenny: Right. Scott is like an expert on behavioral economics as a field. So, I’m going to let him explain what it is.

Scott: All right. Well, please chime in to Jenny. Behavioral economics is really a mountain of sub-fields of the broader disciplines of both economics and psychology. It’s an important component of behavioral science at large. And the general concept is that, we have lots of influences on our decisions all around us, that are foreseeably influential on the choices that we make. And the common thread in all behavioral economic interventions is that, they reliably influence choice without restricting or eliminating choice, or some would say materially changing the incentives to make certain choices or not. Is that helpful?

Eric: That’s actually very helpful. I think when we think about decision-making as we either make decisions or our patients make decisions, we think about it as a rational exercise that they think through the different options, they weigh the risks and benefits on the alternatives. And, I really loved your book, Jenny. It sounds like that’s not always the case, is that right?

Jenny: That’s right. So really, what the book is about in part is really trying to take seriously the findings from behavioral economics and decision psychology about how people really decide. So, one of the things that I talk a lot about in the book are these so-called decisional heuristics and biases. So, decisional heuristics are shortcuts that people use to make decisions that can create certain cognitive biases. So, for example, people are more influenced by whatever they hear first. People are more influenced by, as we just talked about norms, what other people are deciding.

Jenny: They’re most influenced by what’s most available in their mind at the moment, like a particular story or a case example. So, there’s a host of really fascinating findings that are demonstrating the ways that people typically make decisions or things that influence their decisions, that really do the part from, I think, what philosophers and economists have in common, which is to assume a very rational utility maximizing decision-maker. And, the book tries to take seriously what that means for medical ethics, because I think that medical ethics has really inherited a lot of those norms of the rational autonomist patient, making medical decisions.

Eric: And, I’m always impressed when we have people who write books like this. The amount of time and effort, it feels daunting to me. What motivated you to, yeah, I guess even before writing the book, to enter the sphere of behavioral economics?

Jenny: So for me, I had the good fortune of meeting a group of researchers at the University of Michigan. This was at the time their Bioethics Center was also a Decision Science Center led by Peter Ubel, and they had a great group of decision scientists there, Brian Zikmund-Fisher, Angela Fagerlin, and I was just finishing my PhD in philosophy where I had been writing about and studying these very philosophical, rational reason-based theories of autonomy, and I just encountered them and I started hanging out with them and I started going to their lab meetings and learning about all of the psychological realities about how patients really make decisions and started to get really concerned about the challenges that these findings were posing for some of our concepts theories in bioethics, and the way we thought about the ethics of patient decision-making. So for me, it was really happenstance, just encountering people from a different discipline that challenged the views that I was thinking about as part of the discipline that I came from.

Eric: How about you, Scott? How’d you get interested in behavioral economics?

Scott: I actually got interested in it without knowing what the hell it was, but being frustrated as a medicine resident. I was just realizing that I was interested in critical care. And I remember being early in my second year of residency and I was in the ICU, and this was at a time where we thought one of the most important things we can do in the intensive care unit is, elevate the head of the bed at 35 or 45 degree angle to prevent patients from developing aspiration pneumonia when they were mechanically ventilated. And it was absolutely essential that you as the resident wrote an order to elevate the head of the bed to that particular angle, or your attending would totally ridicule you. Now, I started thinking, “Well, if this is so important, and if there are so few cases, sure, the really severe stroke in a patient who is hypotensive, you want might want the bed a little flatter,” but that’s really rare.

Scott: If we want the head of the bed elevated for almost everyone, why isn’t that the norm? Why isn’t it just a default order that the head of the bed be elevated? And then the doc could write an order to have the head of the bed flat in those very small number of cases, in which that would be appropriate. I started thinking the whole system is just backwards. And then, shortly after that rotation, I remember Anelisa, my wife and I were hiking in the Shenandoah Mountains or Shenandoah National Park. And I started talking, I must have sounded like a fool. And I’m sure it wasn’t the most stimulating conversation, but I started talking about all these areas in medicine that I was just like having my eyes open to in which default, which are like the LeBron James nudges, the king of nudges. If defaults are set in, all these hazard and not well thought out ways. And it immediately became clear to me that lots of areas of medicine could be improved simply by changing the way defaults are set.

Eric: Yeah.

Alex: If I could just reflect for a second, I’m noticing and listening to both of you and the stories of how you became interested, that they represent both, Jenny’s talking about how she became concerned about the ways in which nudges might influence the way patients are making decisions. And that Scott was concerned about how lack of nudges or poorly directed nudges would influence physicians to provide suboptimal care for patients in the intensive care units, which is an important realization that these nudges don’t just operate on patients. They operate on the clinicians as well.

Scott: Absolutely.

Eric: What is a nudge though?

Jenny: Well, the way that I think about a nudge loosely is, really just using any insight from behavioral economics or decision psychology, about how people make decisions, and use more subtle ways or quirky ways, or the kinds of ways that are influenced by heuristics and biases, and using that knowledge to rechannel it and shape or influence a patient’s decision-making in a particular direction. And as Scott said, I think people will put a couple of important caveats on that idea, which is that nudges don’t take away options. They don’t coerce people, like punish people if they don’t pick the right choice. They’re not mandates. They don’t force people to do things. And as Scott said, typically, they also are contrasted with incentives, because incentives are more associated with a more traditional economic model of how you might rationally give somebody money to do something because money is a valuable thing.

Jenny: So, I can say for those who are philosophers, there’s a philosopher Yasha [inaudible 00:13:52], who has a really good philosophical definition of nudges. And the way that he characterizes all of these things is really, he calls it triggering a person’s shallow cognitive processes. So, I think that really gets into what nudging is, is kind of tapping into these various shallow cognitive processes to influence a person’s decision in a particular way. Scott, how do you think about nudges?

Scott: Yeah, no, I think that’s spot on. Really, nudges are all around us, and any feature of the choice environment that can reliably and foreseeably influence the odds of making one decision versus another, again, with a important consideration that, if it restricts or removes choice, then it’s not a nudge, it’s a shelf. And, there are many contexts. In fact, one of the key lessons of behavioral economics are the contexts in which nudges are insufficient. And if a particular policy objective is sufficiently important, then we need to go beyond nudging, and then talk about mandates. I know that’s a particularly loaded term these days, but there are lots of spheres of public health where we see fit to not simply nudge choice, but to require certain choices.

Eric: Yeah. In some ways, I’m just thinking about, in San Francisco, you can’t go into a restaurant in-doors and eat without proof of vaccination. So, in some ways there’s a mandate there, but it’s also a nudge. They’re not forcing you to get vaccinated. They’re saying, “In order to eat in-doors, you got to be vaccinated. In order to go to X event, you got to be vaccinated,” but certainly you still have the choice not to get vaccinated, or at some places, you got to get tested like twice a week.

Scott: It may be splitting hairs, but I think most behavioral economists would not consider that to be a nudge, because it is taking away certain options. It’s saying, “You cannot eat in this establishment, if you’ve made the choice not to be vaccinated.”

Eric: I hear the supermarket analogies a lot. If you’re in a supermarket, you avoid the candy aisle at all costs, because you know you’re going to buy it. But the nudge is, right, when you go to the cash register, the candies are right next to you. So, you make an impulse purchase. Is that right?

Scott: Totally.

Eric: So, what’s another example of nudges in medicine?

Alex: Yeah. Maybe in geriatrics and serious illness, palliative care, hospice spaces.

Scott: At one of the ones that I think we increasingly use in communicating with a seriously ill patients and their families is, intentional mindful framing of choices around resuscitation or intubation preferences. I, for many years have modeled. And I hear from trainees, a decade later, that they still use approaches to CPR, DNR discussions where the norm is framed as not providing resuscitation if a patient’s heart would stop. And what that does is it steers people toward a choice that is consistent with what we believe to be appropriate, and the context of a patient who is so sick that CPR would not be beneficial, while still highlighting that there is a choice to be made and giving patients or their family members opportunities to object.

Eric: How do you phrase it from a social norm perspective?

Scott: Oh, so I say in circumstances like this, if your dad’s heart were to stop, we would not normally do chest compressions to try and restart it, because they would almost certainly be an effective. Does that seem reasonable?

Eric: Yeah.

Scott: So the question I’m asking, is whether the recommendation I’m providing seems reasonable. I’m not asking family members to make existentially challenging decisions that will, in many cases, feel highly burdensome and leave them without sufficient guidance.

Eric: And the nudges and the biases that I’m hearing is, “Hey, you’re coming in from a position of authority. There is that social norm bias.” Yeah. Jenny, listen, I’ve actually read your book, and I learned from it. There’s that social norm bias, right? We don’t do this. Sure, you can do something different or saying that, the vast majority of the patients we care for don’t elect to do this procedure. Are those the two that you’re hearing as far as these cognitive biases?

Jenny: I think so. And, and Eric, I’m thinking about another example of a nudge here in this same context that Scott is talking about, which is that, some researchers have done research that has to do with trying to make a certain decision or the effects of a certain decision, more salient or more emotional. So for example, with Scott’s scenario of trying to use social norms to create a nudge around resuscitation, some researchers have looked at the effects of showing family members a really short video, like a two minute video of an actual resuscitation attempt, or to name another example of a patient with advanced dementia. So, there was a study that looked at decision-making around advanced care planning, giving some group of people, a description of what advanced dementia is like. Giving another group of people that same description, but showing them a two minute video of a patient that had advanced dementia. And, they found that the group of people who saw the video, more of those people preferred comfort care only. So, I think that’s another nudged mechanism to give a concrete example, that’s kind of touching on the clinical piece that Scott’s talking about.

Eric: How much of that though is, I’m just providing this person with information to show them what CPR looks like? I’m not trying to frame anything here. I’m just presenting the options so they can make a rational decision.

Jenny: I think that you can definitely make that argument. And some people make that argument. I think, to push back a little bit, I think the more that we learn about behavioral economics and decision psychology, the more we know how certain things we do will influence choice in certain directions, and predictable ways as Scott said. So, I know that if I choose to show a video, I’m going to direct choice in one direction. And I know that if I choose to just give the textual description, I’m going to influence it in another. So, yeah-

Eric: I guess what the video displays too, does it display all of what happens in CPR? Even like advanced dementia, are they smiling and interacting with family members?

Alex: I think this is Angelo Volandes work, right?

Jenny: Yeah, exactly.

Alex: And, we’ve had him on our Podcast a couple of times to talk about that. I think with the CPR, I specifically decided to do it on a mannequin because it felt like the emotional valence of doing it on a human, showing an actual CPR code event would be too strong. And, he received some criticism for the video of the advanced dementia, because it had a video of a woman with her tongue hanging out, and not all people with advanced dementia have their tongue hanging out, and some are dignified. So, that’s availability bias. Is that right, Jenny, to name it and…

Jenny: That’s what he would call it. Yes. That people have that particular case available or salient in their mind and it’s driving their decisions.

Alex: Right.

Eric: The reason I love your book has, A, it goes through all of these different biases, but also, my initial reaction and part of the reason I hate your book was, I understand framing. You present one option first versus the other. I understood the basics. I truly try to figure out first, what are their values and help people make the right choices for them? There was one part on your book around nudging and shared decision-making, which if anybody wants to read one part, I think that part was amazing. And, we even did a New Zealand journal video about how to have these conversations and using aligning statements. Based on what you’ve told me about your values, it sounds like doing CPR may not be the right decision for you. That’s what I do. That’s not nudging. That’s not framing. Then I read the next line, which was basically… It is a nudge, and it does impact decision on a shallow cognitive process due to things like authority bias. Like I’m saying this, social norm bias and desire to appear consistent. What’s that last one, desire to appear consistent?

Jenny: Yeah. So, it’s this idea of like ego, right? That people have ego. It’s not necessarily irrational to have an ego, but just to understand that that’s an important part of psychology for why people might make a decision that they make. And I think it, your example is really interesting, because it’s hard to know, what’s the process that the patient is going through when you give them back that information? That sounds super rational. You’re just like, “You told me your values. I’m a medical provider I’m helping to interpret it. It seems like your values best align with this one option.” In one way, that’s a comparative-matic example of non-nudging. It’s just like-

Eric: It’s what I’ve been taught to do as far as shared decision-making. We’re coming to this together as a group.

Alex: Right.

Jenny: Well, and I’ll be curious to hear if Scott thinks this is a nudge or not. But, I will say, I do a lot of work in decision aid development and I work with a lot of decision aid developers, and all decision aids have this values, clarification exercise, where the patients could go through and rate what matters to them. When I first started working with these teams, I was like, so then we should provide them with the answer. Right. We should be like, okay, the calculation based on your values clarification exercise is, you shouldn’t get to L that. Based on everything you just told me, shouldn’t get to L that. All the decision aid developers I worked with were like, “No, no, no. You can’t tell them. That’s way too directive and nudgey to tell them where their values points were.” So, I think it’s an interesting question. Scott, what do you think?

Scott: That is a great question as to whether that meets the definition of a nudge. I think in many ways, decision aids are a compliment to nudging, but are not typically nudges themselves, or at least they don’t have to be. How’s that? That the goals of decision aids, I think most people… Let me say it this way. Most of the people I know who are developing decision aids, may have in mind, what types of choices they’d like to see made more commonly across a distribution, but don’t necessarily have in mind, what is the right choice for any individual patient, and the goal isn’t really to steer an individual patient in one way or another. And so, in that way, I think the practical clinical use of decision aids could wind up nudging, depending on how the aid is written and framed. But that’s not the under-pinning rational.

Jenny: So, decision aids are part of shared decision-making potentially, right? But to Eric’s sort of thinking about the role of nudges and shared decision-making… One of the things I try to do in that section is basically, I argue for compatibility. In a lot of cases, nudges are going to be part of it and that’s okay, actually. Would you say that nudges are always, or mostly going to be part of shared decision-making? Would you accept that sort of compatibility view, especially based on your clinical experience working with patients?

Scott: Yes. I would say that nudges are intrinsically going to be part of shared decision-making because as you and I wrote, in I think the first paper we ever did together, there’s often no alternative, but to present certain options first, or to frame them as the existing norm or default. It just is that way, and relaying that reality or honoring that reality is in and of itself nudging. So, part of information provision is intrinsically structured in a way that depending on, which of three choices we might list first, is holding a privileged position? And absent strong preferences is going to be chosen more often than the others because to forego the first option presented, strikes against our natural loss of first instincts.

Alex: Yeah. You had a quote in your conclusion of your book, Jenny from I think Cass Sunstein and Taylor, but if you are a doctor, you are a choice architect. If you are a doctor, you are talking to patients about choices that they’re making and alternative options. You are a choice architect. It is inescapable. One of the key points that you hammer home is that, we can’t escape nudges. We are nudging all the time and that we should be more aware of the nudges, and thoughtful about our approach to nudging people. That’s what I took away from it. Like Eric, I also have a concern about nudging. And, in your book, you’re very clear that we need to start with goals and values, and that nudges are not appropriate for all circumstances.

Alex: There are other circumstances where it’s much more appropriate to proceed with rational deliberation discussion and yet, I worry that some people may say, take Scott’s CPR code phrase or phraseology and use it with all patients, without first assessing what their underlying goals and values are. So that nudges like the force, can be used for great good or great evil. Communication itself has the potential to be really beneficial and really harmful. And, we as doctors have a tremendous responsibility to attend the way in which we communicate to patients thoughtfully. Unlike the force, which is concentrated in only a few people with medical [inaudible 00:30:40], let’s see how far I can take this. Nudges are ubiquitous and we can’t escape them. Everybody is doing it all the time. So for people like Ken Covinsky, who’s often a host in this Podcast, hates nudges. Ken, wake up. You’re nudging people. Right?

Scott: Is that why so many of my papers get rejected from … [laughter]

Eric: You just have to nudge better, Scott. You have to nudge better.

Jenny: That was a Star Wars reference, right? I feel like I got it, because it’s not predictable that I would. But yeah, so I would say, one of the things I do in the book… I’m on board with Taylor and Sunstein with their inevitability thesis. And I think the implication is, as you said, we can’t just wash our hands. I feel like clinicians and bioethicists have had this easy answer of like, “I just don’t influence. I just stay out of the way and let patients make their autonomous decisions.” And, feel like we can’t get off that easy. So, I buy into their inevitability thesis, a great deal. But at the same time, one thread that I do try to repeat throughout the book, where I think they’ve oversimplified a little bit is, we can nudge more or less. Meaning that, sure we’ve got to make a decision.

Jenny: Oh, my gosh, what do I talk about first? Oh, my gosh. Like, what am I wearing? Am I wearing my white coat, or am I not wearing my white coat? Those are decisions you have to make, but doing stuff like showing a two minute video of somebody who died, or showing a picture of somebody who died because they didn’t get a vaccination, or something like that. Those are all extras. I would argue that there are some types of nudges that we decide to introduce. And, that’s fine. They might be justified, but I don’t think that we can get… Maybe that’s why some people hate nudges, and then yes, of course, they can to be used for good or bad.

Jenny: And I don’t have a magic fix to figure out how to get clinicians, to make sure that they accurately figure out what matters to patients and what is in their interest, before they engage in nudging. But, I count on my physicians to do that. I count on medical training to develop their characters and create a sense that they have professional obligations to me. So, I hope I’m not too naive in that realm. I think if they’re reflective about it, I’m less worried about force for bad.

Eric: Which is interesting, because it is with great responsibility-

Alex: With great power, comes great responsibility.

Eric: Yeah. The other way.

Alex: Spiderman.

Eric: Being mindful of our nudges and when we’re using it… Actually, learning about nudges gives you power, and potentially power for good and the interests of our patients, or power to go in the wrong way. Is it okay if I just read one paragraph from your book? Is that okay? I know I usually hate saying this, Alex, about paragraphs, but I thought this was exceptionally… So Jenny, you are a philosophy. You did philosophy as undergrad, right? And you love hiking in state parks.

Jenny: Yeah.

Eric: So, you’re right about this hypothetical example in the future. First, your doctor flashes a toothy smile and tells me that he too studied philosophy as an undergraduate and enjoys spending time hiking in a local state park. By doing so, he immediately gains my trust and becomes a person like me, increasing his propensity to become an influential messenger. And I think in palliative care and geriatrics, we try to build rapport-

Alex: That’s step one, form a relationship.

Eric: Build rapport. What I’m actually doing is I’m nudging, I’m becoming an influential messenger. What is an influential messenger? What was the bias there?

Jenny: Well, it’s just that you’re influenced by the messenger her or himself as opposed to the value of what they’re giving you reason to do. Right. This actually just happened to me. I had an eye surgery, not this exact example, but I recently had an eye surgery and I wouldn’t have had it. Eye surgery creeps me out. But the eye surgeon, he was like, “I’ve had this surgery three times. I have this same condition.” It was strabismus. He’s like, “I’ve had strabismus. I’ve had this surgery three times.” He was like, “You love to swim. I love to swim.” And I was like, “Oh, my God.” I was just like, “Sure, I’ll have the surgery. Great.”

Eric: Influential messenger. I love it. Then you go on to talk about an LVAD decision in the future, talking about the risks and benefits. But then the doctor says, “Most people like us who are young and active, would never get the device, at least not until it’s the last resort. But I don’t have to tell you that. You’ve seen a lot.” So, he’s using social norms and appeals to your ego, right?

Jenny: Yeah.

Eric: And then finishing off, he says that he will tell the rest of the medical team to hold off before going into that direction. “But I should let him know if I feel differently after I’ve had a chance to review the decision aid, so he sets a default. Leaves the form with me, that has decline the LVAD checked as the default and asks me to sign it again, but lets me know that if I want to, I can scratch it out and change the selection.” Scott, you’ve talked a lot about your interest, and I know you’ve done and work in defaults. First of all, what’d you think about that paragraph? And, how should we think about defaults?

Scott: Well, I love the paragraph and I would say to bring this into the palliative and supportive care space, very centrally, is to recognize that by default, life sustaining care will be provided to every American. That is the embedded social default in our society. And, I don’t actually quibble with that. If we need one default and we do absent a goals of care conversation or a values elicitation process, that’s a reasonable way to go. We don’t want the 20-year-old on the basketball court who has a sudden cardiac arrest to not get resuscitated unless his mom is in the stands saying, “Please, please resuscitate my child.” That’s not what we want. We want to provide appropriate life sustaining or life restoring therapies, when they might work. But by the same token, as anyone who practices medicine in a space that touches on patients with chronic serious illnesses that are more likely than not to be the cause of their death in the near term, we need to take opportunities to address that embedded default head on, because to not do so is to abandon our responsibility, to at least try to provide golden court and care.

Alex: Scott, could you tell us about your studies, changing the defaults on advanced directives?

Scott: Oh, sure.

Alex: On high level. Yeah.

Scott: Yeah. So, we’ve done now two randomized trials. One a pilot study and then a larger study in a more diverse population with longer follow-up, that randomized patients with chronic serious illnesses, with limited life expectancies who had not already completed an advanced directive to one of three versions of an otherwise identical state authorized advanced directive. And the control condition asked people to state their overall goals of care and their choices to receive or not receive things like CPR, mechanical ventilation, dialysis, feeding tubes, those are the main ones. And then, in a one alternate form, the comfort oriented default, the choices were framed such that the option to prioritize comfort over life extension, if those goals were to come into conflict, was pre-selected. But people were instructed that they could just cross that out, and instead select a choice to prioritize life extension over comfort, or to not make that choice of at this time, which by the way, is effectively defaulting to surrogate decision-making.

Scott: And then, a life extension default, basically defaults to life extension. And it’s structured in exactly the polar opposite way of what I just described. And then, people complete the advanced directives, perhaps with their family members or loved ones, send it back to us. And then, to make these studies ethical, we then call people up and say, “Okay, here’s what we did. You got this particular version of the advanced directive, other people in the trial got these other versions. Now, we want to go through each choice that you made before we scan this into your electronic health record.”

Scott: So, we have that debriefing process. And the amazing thing is that, even during that debriefing process, people make almost no changes to the choices that they had made upfront. And yet, the defaults hold enormous influence on people’s likelihood of choosing comfort oriented care, their likelihood of choosing to be DNR, to be DNI, not to be intubated, to not receive… All those things, like doubling of the rates of people making those choices. And even when we unblind them, so to speak, to what we actually did, they’re still cool with the choices they made. And then those advanced directives get scanned into the EHR. So, what that says to me is that, people don’t have deep-seated preferences, well-ordered preferences about these choices, because if they did, the defaults could not possibly be so influential, particularly when we told people exactly what we’re doing.

Alex: Right.

Eric: Well, I got a question on that part. So, while there’s a significant change, not everybody changes. Right. Right. So, nudges only goes so far. And I wonder, bringing it home to this question is, is it… I recognize I’m reading your book, Jenny, that we use them. You can’t avoid them. Is it ethical to use them… I’m just, again, Scott reading your paper that came out. What article was that in the table, Alex?

Alex: Oh, right. I have it up somewhere here.

Eric: Was it JJ? I forgot which one, but as Alex looks it up, using a social norm. So, they’re likely to agree with a choice others have chosen. So using in a statement, “Many patients in this situation would not want chest compressions if their heart stopped. Does that also reflect your mother’s wishes?” Is that an okay statement to make from…. Is that an ethically defensible statement to make, or should we not be using those statements or does it go back to, it depends on what their values are? And, is it value congruent? Are their values even stable, like in Scott’s paper? Do we have these deeply-held values?

Alex: Right. Briefly, that was Intensive Care Medicine, 2016 Anesi and Halpern.

Scott: Yeah. Yeah. So at first to give credit where it’s due, George Anesi is a faculty member here at Penn, was the first author of that piece. And, I know he’d agree with the statement that, we provide those as examples of language that could be used, not recommendations that that language should be used, but rather a reflection of the power of the language that the clinicians do employ. I completely agree. And Alex said this earlier, that statements that foreseeably increase the odds of certain choices, ought to follow from an engagement in what the goals of care are and ought to be. They should not lead that discussion. There are exceptions in the ICU, but these are the exceptions, not the rule where a patient is newly admitted and is going to foreseeably have a cardiac arrest, in moments, right.

Scott: That may be a case where a nudge absent, a goal’s resuscitation needs to happen when there’s almost certainly no benefit to do brought by CPR. And yet, that is the underlying social norm, absent a discussion, or at least in ascent. Randy Curtis, who was on your Podcast recently, had a lovely piece with a another scholar who Alex and Jenny know, the late Bo Burt, looking at the concept of informed ascent, which is basically notifying someone that a choice is being made, and just looking to ensure that they don’t dissent to that. And that’s a good context for where that concept might apply.

Eric: Yeah. All right. Jenny, my last question for you, I recognize we’re at a time, if you had a magic wand, you can make one change about what providers do around behavioral economics, what would you want them to do?

Jenny: I would love for them to get out of the mindset of neutrality is the only way to respect patient autonomy.

Eric: Great. It sounds like from all this, my main lesson is you can never be completely neutral.

Jenny: Yeah.

Alex: Right.

Eric: Scott, do you have one magic wand thing that you would want?

Scott: That is exactly along the lines of what I was thinking. Let’s see. I’d like for people to also, in addition to that and perhaps part and parcel to that, to actually think about the way they order choices, even if they’re not explicitly trying to nudge certain ones, that simple choices about if you’re providing three options for the next steps in patient care, the order in which we present them actually has some meaning and ought to be done with some intentionality, not just totally have options.

Eric: And even the number of options we give them. Right?

Scott: Yes, indeed.

Eric: Like, the Starbucks latte sizes.

Scott: The more options you give, the more likely someone’s going to choose the middle one.

Eric: Well, Jenny, Scott, big thank you. Before we end, let’s let’s hear a little Dylan, but real quick, where can we buy your book, Good Ethics, Bad Choices?

Jenny: It’s MIT Press, and you can buy it on Amazon or MIT Press.

Eric: Great. And we’ll have a link on in the Jerry Powell Show notes. Alex, you want to end us off with a little more Dylan?

Alex: (Singing).

Scott: Wow.

Eric: Thank you. Scott, Jenny, big thank you for joining the Podcast.

Alex: Thank you.

Eric: And, thank you, Archstone Foundation, and to all of our listeners. Most of our listeners put in reviews on iTunes, about how much they like the show- [laughter]

Scott: And most of our reviewers give us five stars. [laughter]

Alex: I think, and that just be based in truth, Eric. [laughter]

Jenny: I’m sure it’s.

Eric: I like Podcasts like you like Podcasts. I review Podcasts, all the time. [laugher]

Alex: All right. Thank you so much, Jenny.

Eric: Goodbye, everybody.