The National POLST Paradigm Task Force (NPPTF) has just released their updated “Appropriate POLST Paradigm Form Use Policy,” which can be accessed at http://bit.ly/2pJuRmt. So I’ll just start by disclosing that I am very fond of POLST (Physician Orders For Life Saving Treatment).

I believe POLST has made an appreciable and important difference in the lives of many patients and their families. The POLST paradigm is sometimes misunderstood, both by clinicians and members of the public, and I want to share some reminders from the National POLST Paradigm Task Force (NPPTF) about the appropriate use of POLST forms and their kin (MOLST, MOST, POST, COLST, the very catchy T-POPP, and others), now considered endorsed or mature in 24 states, and at varying levels of development in 24 more.

The main point is that, unlike an advance directive, POLST is not for everyone. And POLST is more than just a form in a chart, it’s a concept that invokes a diligent conversation (or more) between a clinician and a patient/family, then translates it into actionable orders.

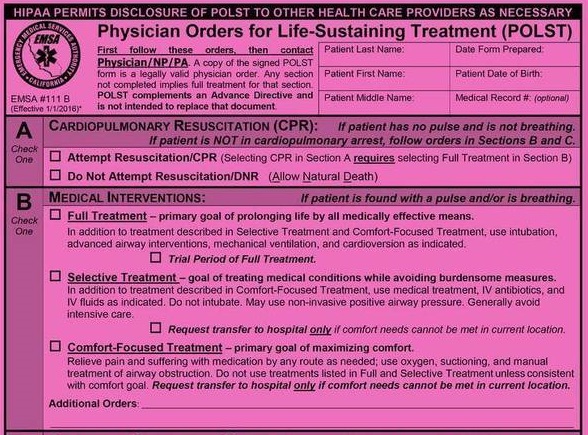

Wearing my two related hats as a long-term care geriatrician and palliative medicine specialist, I have been a big proponent of the POLST Paradigm since I first heard about it back in the second millennium. In California, we borrowed heavily from the Oregon POLST form and worked extensively with a wide coalition of stakeholders with very divergent opinions about end-of-life care to come to a consensus before we got AB 3000 passed in 2008, with our POLST form becoming effective at the beginning of 2009. Since then, we’ve made some improvements (at least we think so), including changing some of the language (e.g., from “limited” to “selective” for the middle-ground option, and from “comfort measures only” to “comfort-focused treatment,” and adding a “trial period” of full treatment). We really like our pink friend, the POLST form!

I’ve been a nursing home medical director and a hospice medical director since 1995 (before it was fashionable or in demand to be a palliative care doc). One of the most meaningful things we do in our line of work is to help patients and families make informed decisions about the kinds of medical treatment they want or don’t want.

Back in the olden days, I would spend a good chunk of time at the nursing home bedside having these goals-of-care/advance-care-planning discussions, and often after the discussion, a decision would be made to forgo CPR in the event of a cardiac arrest. I would write an order and sign the “PIC” (preferred intensity of care) or “PIT” (preferred intensity of treatment) form required by the facility, and while the patient was within the four walls of the facility, the order was valid. However, as soon as the patient left to go home, it would be as if the discussion had never occurred. Or if the patient had to go to the hospital, the order had no authority. Many times, patients wound up getting treatments that were not concordant with their wishes.

POLST changed all that. I could spend that important time at the bedside, usually much appreciated, and then create an enduring document that was sent home with the patient and put on the refrigerator or bedpost (not secreted in a safety deposit box somewhere like most advance directives), and faxed to the primary care doc. It would also accompany the patient if they had to go back to the hospital—where usually, it is actually honored. POLST is practical, reasonably simple so that first responders can act promptly, and most importantly it allows patients to have their wishes respected. They can request the most aggressive treatment, or can request to forgo treatments. As long as they have decisional capacity, they can change their request at any time depending on their condition and other life circumstances or attitudes.

But back to that key point: POLST is meant for patients who are nearing the end of life. It is not designed to be completed by young, healthy people or even by elderly patients who do not have the expectation of limited life expectancy (although of course, for patients with very strong feelings about their wishes—whether it be for aggressive medical interventions or for comfort care, or something in between—it may be reasonable for a clinician to consider completing a POLST).

However, clearly, not every patient entering a nursing home—for example, a healthy 66-year-old who had a knee replacement and just needs a few days of rehab because she doesn’t have an available spouse or adult child to help her at home—should be asked to complete POLST.

Some nursing homes use POLST as a code status document that is considered part of the routine admission paperwork, which degrades the sanctity of the concept and runs counter to the POLST paradigm. In fact, some states have a requirement for nursing homes to complete POLST on every admission—a requirement that renders those states non-endorsed by the NPPTF.

One reason for this should be obvious: If a patient completes a POLST when reasonably healthy and chooses full treatment, including CPR—then loses decision-making capacity—it creates a potential conflict when a change in medical condition creates the need to change the goals of care. A family member or other agent is now faced with saying, “Yes, my mom signed yes to CPR 10 years ago when she had her knee replaced, but now that she has severe dementia and pancreatic cancer, I am certain that she would not want any life-prolonging measures, and she’d want to focus on staying comfortable.” That conflict may be both emotionally difficult for a family member and confusing to healthcare practitioners.

Since many patients do not designate a surrogate on any legal document (like an advance directive), a family member or other individual who knows the patient well is generally the person who helps us write orders that comport with the patient’s known and expressed wishes, or at least the type of substituted judgment that comes from knowing a person well. There is also the best-interest criterion when wishes are not known, which can be a morass—but again, a person who knew the patient when he/she was intact would be best situated to help us determine what would be in his/her best interest.

In fact, in some states, a surrogate who does not have formal legal standing (like being named in an advance directive)—even a spouse or parent of an adult—would not be permitted to change a POLST paradigm form in these circumstances. That would be extremely unfortunate in a situation like the one described above. It goes against the whole notion of surrogate decision-makers that we rely on so frequently in our work. We do not want people to be forever locked into being treated in a way that they would no longer desire, just because of a form they may have signed years ago when things were very different.

Another misconception I’ve seen recently in the literature and out in the field is the idea that “DNR/DNAR/AND” (do not resuscitate/do not attempt resuscitation/allow natural death) is somehow inconsistent with “full treatment” on a POLST form. GeriPal readers, please educate your colleagues about this important point! DNR does not mean “just let me die.” (Actually, please educate your patients and their families about this too.) Section A of the POLST (CPR preferences) applies when somebody has no pulse and is not breathing. In other words, in a cardiac/respiratory arrest. Or, as some would say, dead.

If the patient is not in an arrest situation, Section A does not apply. In that case, you go to Section B (medical treatment preferences). If it says full care or full treatment, that means yes, you intubate that patient who is in respiratory failure when CPAP fails. It is disappointing to me when my colleagues seem to struggle with this concept, and it feels like a bit of a failure on the part of our community to do robust education on these important nuances.

Clinicians, educators, academicians, everyone: I urge you to review and widely disseminate this policy document and the information contained within, among our peers and our patient population. It is vitally important, especially given the current political and regulatory climate, that POLST be utilized in an appropriate fashion, and not misused in a way that might create unintended harms to the patients we so conscientiously strive to serve.

Dr. Steinberg is a longtime nursing home and hospice medical director in the San Diego area, editor-in-chief of Caring for the Ages, chair of the Public Policy Committee for AMDA—The Society for Post-Acute and Long-Term Care Medicine, a member of AAHPM’s Public Policy Committee, and a consultant member of the National POLST Paradigm Task Force’s Executive Committee. He can be contacted at karlsteinberg@MAIL.com or via Twitter at @karlsteinberg.

Learn more about the California POLST form at CaPOLST.org

by: Karl Steinberg