As a geriatric fellow back in the 1980’s I became intrigued by the wide prevalence of pressure ulcers and how little literature there was on this disease. Three decades later, they have not gone away and it amazes me that they are not on the list of recognized public health threats.

According to the Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research, pressure ulcers affect up to 2.5 million patient per year, and related costs range from $9.1 to $11.6 billion per year in the US. Complications include pain, scarring, infection, prolonged rehabilitation, and permanent disability. They are largely preventable, and 60,000 patients die as a direct result of pressure ulcers each year. They are common across the healthcare continuum, and as many as 42% of patients in ICUs and 28% of hospice patients have pressure sores. According to a recent NPUAP monograph, pressure ulcer prevalence in long-term care ranges from 4.1% to 32.2%. Pressure ulcers are closely associated with the perception of quality, and have become a risk-management burden for practitioners and facilities caring for patients with this disease. Despite these pressing concerns, pressure ulcers are not on the research funding agenda of the CDC.

The statistics on pressure ulcers are eye-opening when compared to other, more widely recognized public health threats including influenza and gun related deaths. Influenza results in 36,000 deaths per year, and deaths in America from guns number roughly 32,000 per year. Pressure ulcers therefore cause nearly as many deaths per year as influenza and guns combined. The 2016 fiscal year budget for the CDC includes a request for $10 million for gun violence prevention research. There is already $187.5 million allocated for influenza planning and response. But there are no CDC funds allocated or requested for research on prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers.

Given their prevalence, morbidity, and cost, it is puzzling that pressure ulcers are underappreciated as a public health issue. Plaintiff attorneys have certainly caught on, with more than 17,000 lawsuits annually. Perhaps it’s time to face this issue squarely by recognizing its importance and scope and increase funding toward research on pathophysiology, prevention, and treatment. Here are some avenues that require resource allocation:

- Defining skin failure and the pathophysiology of skin changes at life’s end, and its impact upon prevention and avoidability.

- Development of improved prevention technologies.

- Development of technologies for early detection of deep tissue injury.

- Development of improved electronic records that explicitly incorporate systems impacting skin assessment, prevention, and treatment.

- Defining molecular mechanisms of tissue tolerance including inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, oxygen homeostasis, mitochondrial dysfunction, and vascular hyperpermeability.

- Defining the unavoidable pressure ulcer, with development of a sound algorithm for determining when these wounds are preventable.

- Developing evidence based, cost effective wound treatments.

- Defining when wounds become palliative and applicable treatment protocols.

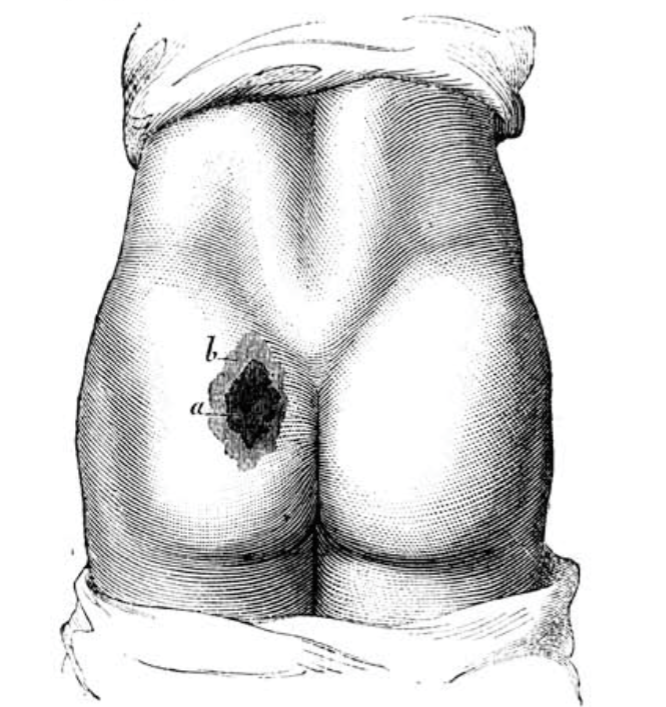

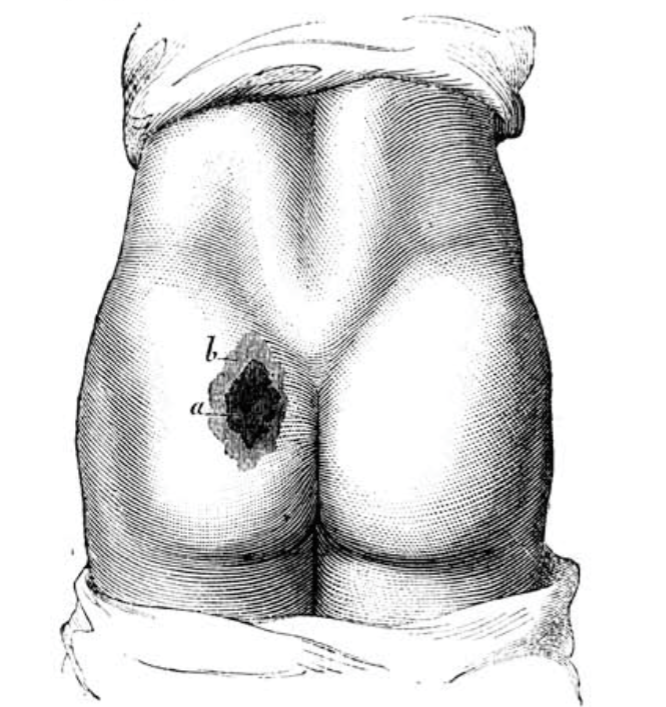

In the 1800’s one of the greatest minds in medicine,Jean Martin Charcot, studied pressure ulcers but his example was not followed. Over a century and a half later, wound care shares little space in the medical school curriculum and most doctors receive little training on pressure ulcers. However the imperative for physicians to become more involved in wound care has grown as their prevalence increases with the elderly demographic and improved technologies to keep people alive. As pressure ulcers are an acknowledged geriatric syndrome, geriatricians are in a perfect position to help fill this gap. However pressure ulcers are a problem that geriatricians cannot tackle alone. Preventing and curing pressure ulcers is a multidisciplinary endeavor that will require allocation of resources to research, technology, systems improvement, and manpower.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

References for this post include:

Pieper B (ed). Pressure ulcers: Prevalence, incidence, and implications for the future. NPUAP 2012.

Inouoye et al. Geriatric Syndromes: Clinical, Research and Policy Implications of a Core Geriatric Concept. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007 May; 55(5): 780–791.

Molinari et al. The annual impact of seasonal influenza in the US: Measuring disease burden and costs. Vaccine, 2007; 25 (27), 5086-5096.

AHRQ. Preventing Pressure Ulcers in Hospitals. http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/systems/hospital/pressureulcertoolkit/putool1.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_motor_vehicle_deaths_in_U.S._by_year

http://www.cdc.gov/budget/documents/fy2016/fy-2016-overview-and-detail-table.pdf

Burt T. Palliative Care of Pressure Ulcers in Long-Term Care. Ann Long-Term Care 2013; 21(3).