Eric Widera, MD (@ewidera)

In 1824, Jeremy Bentham published the “Book of Fallacies” in which he criticized fifty arguments used in political debate and explained the sinister interests that led politicians to use them. One of these fallacies he describes as the “sham distinction”, now known better as a “distinction without a difference“. This logical fallacy appeals to a distinction between two two things that ultimately cannot be explained or defended in a meaningful way. When it comes to cancer and non-cancer pain, one really must question why we are drawing a distinction between these two entities and whether it is science or politics that that demands there be a difference.

The Origins of the Distinction

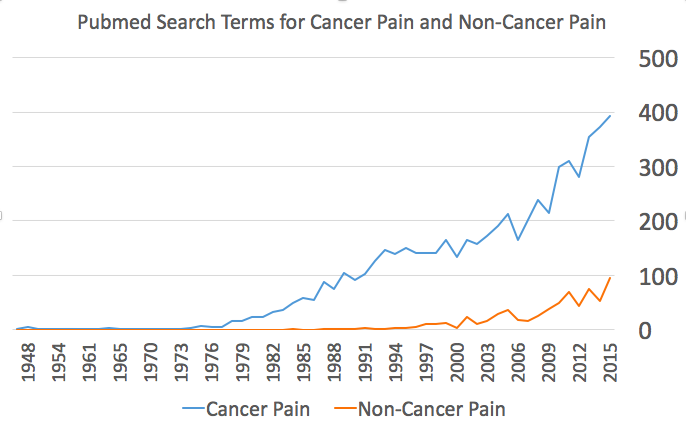

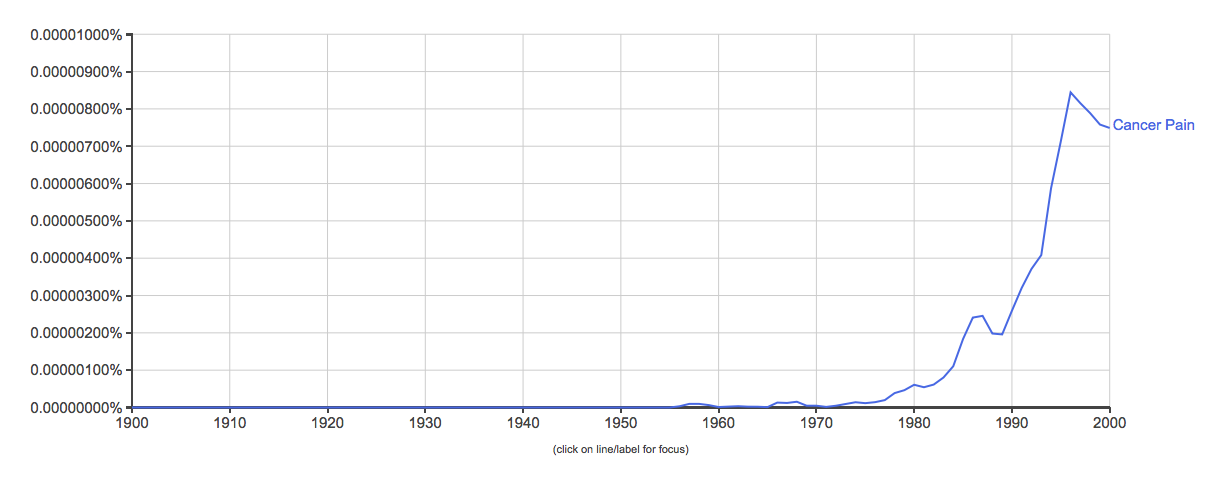

The term “cancer pain” is relatively new, appearing in greater frequency over the last three decades in both medical journals (Figure 1) and in printed books (Figure 2). Cancer was viewed as the emperor of all maladies, and pain one of its most feared outcomes. Use of opioids for cancer pain was encouraged as patients were suffering and the prognosis of their malady inevitably led to short term use.

|

| Figure 2: Use of the phrase “cancer pain” in printed media via Google Ngram |

You can also see in figure 1 that the term “non-cancer pain” started to take off about two decades later. As noted by an article published last week by John Peppin and Michael Schulman, “those using the term “chronic noncancer pain” were in two camps: those who felt that opioids should be avoided in patients without cancer, and those who felt they were yet one more tool for the treatment of these patients.” A good example of this is an article published in 1995 titled “Opioids for chronic pain of non-malignant origin–caring or crippling” in which an evolution of a distinction was discussed but no significant evidence is given to support a difference:

The world of pain management, therefore, has evolved two very different models of managing pain. A drug treatment model with a strong emphasis on diagnosis for acute pain and cancer pain; and a behavioural, coping skills model for CPNMO [Chronic Pain of Non-Malignant Origin]. It was inevitable that clinicians versed in one model would begin to apply those principles to the management of pain in the other category.

The Logical Fallacy

The problem with this distinction is that there is very little evidence to support a difference between these two broad categories. As Peppin and Schulman point out:

“These claims are primarily philosophical, rather than medical or physiologic. As mentioned, pain mechanisms do not discriminate between cancer and noncancer pathophysiology. Patients with cancer or those without cancer have essentially identical pain-generating physiologies, and thus the same mechanisms for the development of their pain (eg, inflammatory pain in a cancer patient will be the same physiological process as in a noncancer patient). Further, cancer patients are living longer and their original pain generators become chronic pain in and of themselves, little different from patients without cancer.

Even if you are more of a splitter than a lumper, it still doesn’t make sense when you include what we know about the biology of cancer. Cancer, despite recent “moonshot” ideas, is not a single entity. There are numerous types of leukemia, lymphomas, skin cancers, bones cancers, lung cancers… The list can go on and on. The etiology of pain that may result from these cancers also vary: it can be due to muscle damage, bone invasion and central sensitization, nerve impingement or destruction, chemotherapy induced neuropathy, liver capsular expansion, and on and on the list goes.

From a medical and scientific aspect, it makes little sense to have these two broad categories of chronic pain. But from a political and emotional aspect, it may make ones life a little easier, because who doesn’t want to relieve the pain of a dying cancer patient. But what about a cancer survivor? Are they still considered to have cancer pain once the cancer is cured? What if the pain is due to chemotherapy-induced neuropathy? Who will fight their battle politically?

The Alternative

While it may feel wise to distinguish the terms cancer and non-cancer pain from each other, continued promotion of this idea is fraught with logical fallacies, and is best defended by emotions and politics rather than the state of science.

The alternative is to abandon the distinction for all of these reasons and use terms that actually help us understand the nature of an individuals pain and how best to manage it, which may or may not include opioids. As Peppin and Schulman suggest:

Perhaps a more prudent, less charged set of terms would indicate the origin and generator of the pain. Therefore, a patient with chest-wall pain from radiation due to breast cancer would be labeled “chronic pain of breast cancer radiation-treatment origin”. The patient with pain from an advanced spondylolisthesis would be diagnosed with “chronic pain of spondylolisthesis origin”. The goal here is to continue to be patient-focused, relieve their suffering (instead of contributing to it), and help improve their lives.